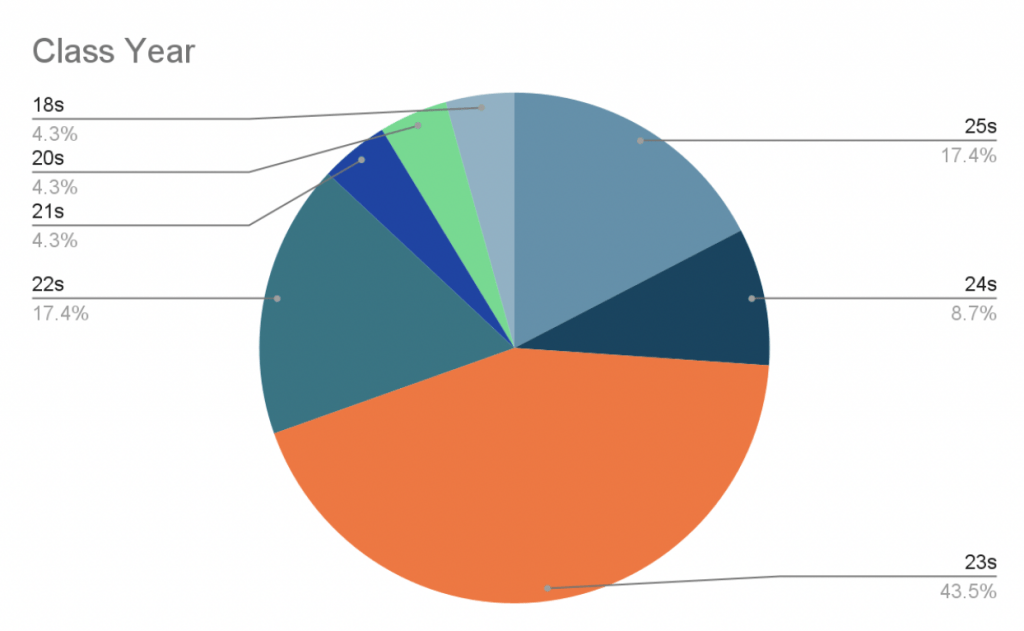

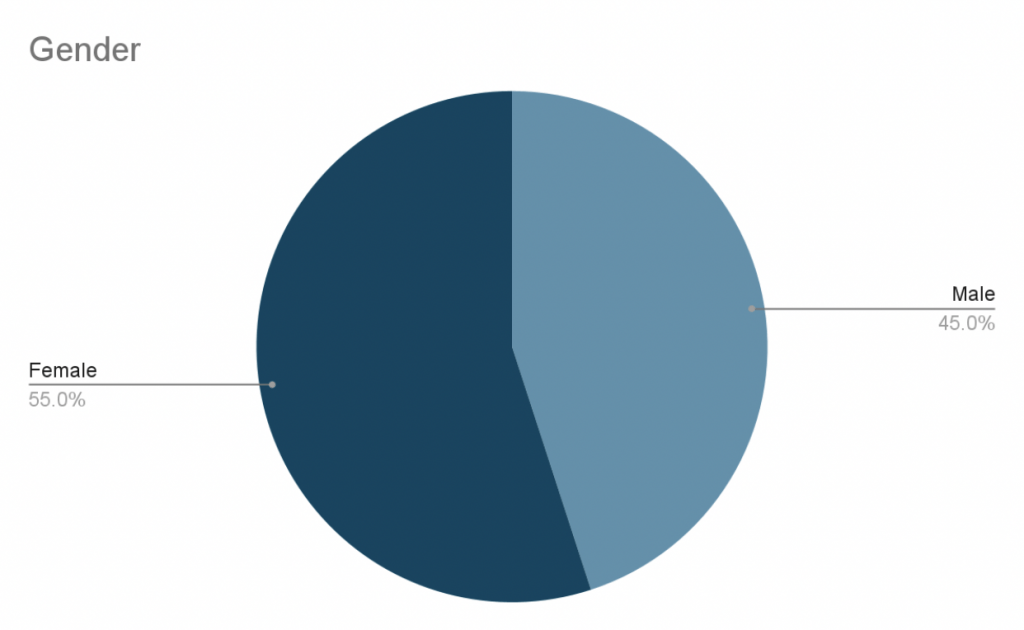

For our group’s project, we decided to focus on football locker room traditions across the country. With the majority of the group members being football players themselves, this topic was particularly important to us. We made sure to focus on locker room traditions for both current and former football players. We made sure that we found folklore that was performed by two or more members of a team in a locker room because a defining characteristic of folklore is that it is shared among a group of “folk”. Our group had six total members and collected thirty pieces of folklore from thirty different sources. We interviewed both current and past football players from across the country. The interviewees spanned from 18 to 37 years old from a variety of schools across the country. Our interviews focused on specific locker room traditions at each school along with the potential meaning behind the tradition.

The folklore that we collected spanned a wide range of customary, material, and verbal folklore with a majority of items collected being fight songs and post-win traditions. Overall, there were a few interesting findings that our group took away from the collection process. The first takeaway is that despite the wide range of ages interviewed, traditions did not seem to change very much. Most of the traditions that were collected had been in practice for as long as anyone on and within the team remembers. Additionally, we found that most of these traditions were learned upon each interviewee’s arrival to their university and it was primarily the job of upperclassmen to continue to pass the tradition. Football is the ultimate team sport in which many times over one hundred individuals come together to achieve one common goal. Each player’s job is unique in and of itself but it’s the culmination of all the players that allows for a team to be successful. Therefore, some of the common overarching themes that we took away from the collected traditions were to invoke school pride, foster comradery, and take ownership of the locker room. In addition, football is both a mentally and physically taxing sport so some more themes that we found included providing motivation to compete and initiating an individual into the team.

As a group, we really enjoyed the collection process and hope you both enjoy and learn something from our collection. See the attached file for the presentation we have in class on 11/10/21.