Climbing Status Symbol

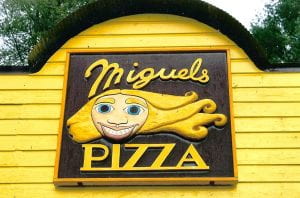

“Miguel’s Pizza”

Decker Wentz

Hanover, NH

May 22, 2019

Informant Data:

Decker Wentz is a 20-year-old sophomore at Dartmouth College. He grew up just outside Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Decker has been rock climbing with his dad since he was four years old. He would climb about monthly with his dad, going to climbing gyms but mostly climbing at various outdoors locations. In his senior year of high school, he began to really take ownership of climbing as an activity that he loved doing, not just one that he did with his dad. When he came to school at Dartmouth, it became one of the most important things in his life, as he joined the Dartmouth Mountaineering Club (DMC) and the Climbing Team. His first DMC trip was an ice climbing trip his freshman winter, and since then he has become more and more involved in the club. Decker is now a leader in the DMC and currently holds the position of chair. He has also been quite an involved member in the social aspects of both clubs.

Contextual Data:

- Social Context: This piece of folklore was collected in a conversation with Decker at Baker-Berry library. Decker first learned about Miguel’s Pizza in a conversation with other climbers where one pointed out another’s “Miguel’s Pizza” sticker, which started a conversation. It is not incredibly common for someone to start a conversation on the basis of seeing the Miguel’s logo, but it is widely recognized if a climber sees another climber with it. Miguel’s Pizza is a pizza place and campground located in the middle of Red River Gorge, a famous and very difficult climbing area located in Kentucky. If a climber goes to Red River Gorge, Miguel’s is the place to stay and to eat. Therefore, the easily-identifiable logo is a sign to other climbers that the person possessing it has climbed at Red River Gorge.

- Cultural Context: Since Red River Gorge is an incredibly good destination for climbing on the east coast with difficult climbing, almost all serious American climbers on the east coast know about it, know about Miguel’s Pizza, and associate the two. Therefore, a climber who goes to Red River Gorge is considered a strong climber. However, as the scope of climbers becomes broader, Miguel’s and Red River Gorge becomes less and less well-known. Generally, American west coast climbers may still recognize the logo of Miguel’s Pizza and associate it with Red River Gorge. However, it is not very well-known in the international climbing community outside of the United States.

Text:

Miguel’s Pizza is a pizza place and campground located in the middle of the Red River Gorge climbing area in Kentucky. Miguel’s is known as the place to stay and to eat when climbers go to Red River Gorge, and has a very distinctive logo that says “Miguel’s Pizza” and has the image of a man’s smiling face with flowing blonde hair. After visiting Red River Gorge and Miguel’s, many climbers buy merchandise with the logo on it. Because of this, Miguel’s logo has become a status symbol within the climbing community because the logo indicates that the possessor has climbed at Red River Gorge, which means they must be a very good climber.

Sam Drew, Age 20

Hinman Box 0250, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH

Dartmouth College

Russian 013

Spring 2019