“The Mystic Day”

This week brings the Spring Equinox, and with it, the burgeoning scenery and release from winter that inspired Dickinson to write some of her most celebrated nature poems.

Even as a child filling in herbarium books and studying natural sciences, Dickinson had an affinity for the natural world, and nature comprises a critical part of Dickinson’s poetic language. She uses flowers as powerful symbols for herself and her poetry, butterflies and bees as recurring characters under intoxication, birds as divine and philosophical beings, and the sun as an eternal clock that marks the changing of the human world.

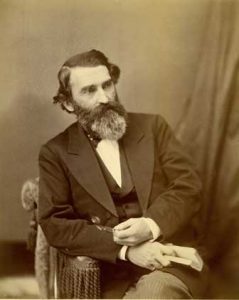

To glimpse what spring, in particular, meant to Dickinson, we might delve into what Barton Levi St. Armand called Dickinson’s “mystic day,” an elaborate symbolic system that synthesizes what he determined are Dickinson’s mythological associations among the seasons, four directions, times of day, flowers, colors, geography, psychological states and emotions. He is working from Rebecca Patterson’s outline of Dickinson’s “private mythology” in which Patterson claims that

by means of these interconnected symbol clusters [Dickinson] has effectually organized her emotions and experience and unified the poetry of her major period, making of it a more respectable body of work than the faulty and too often trivial fragments in which it is customarily presented.

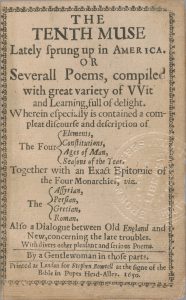

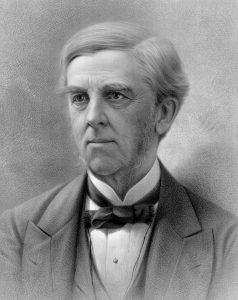

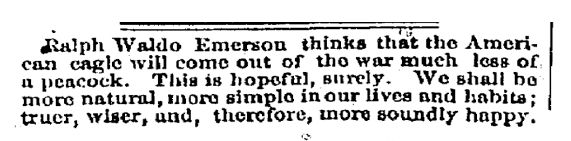

St. Armand notes that such symbolism was not unique to Dickinson and resembles “the fourfold universe of William Blake’s prophetic books, especially The Four Zoas” (begun in 1797), while fellow New Englander Ralph Waldo Emerson also provides “a stimulus for the development of such an elaborate map of consciousness” in Nature (1836) when he remarks:

the dawn is my Assyria; the sunset and moonrise my Paphos and unimaginable realms of faerie; broad noon shall be my England of the senses and the understanding; the night shall be my Germany of mystic philosophy and dreams.

St. Armand speculates that drawing on the associations in the mystic day was a way for Dickinson to solve the dilemma of temporality—how to access the eternal world while trapped in human time—by collapsing human time into eternity and representing one mode of time through the other. This personal system of correspondences was quite elaborate, as St. Armand’s chart indicates.

from Barton Levi St. Armand, "Emily Dickinson and her Culture," p. 317

In this system, Spring is associated with the cardinal point of the East, the human cyclical event of birth, the Christian cyclical event of the Resurrection or Easter, the spiritual cycle of hope, the psychological cycle of expectation, the colors of amethyst and yellow (for the dawn), the flowers of jonquil and crocus, the geographical places of Switzerland and the Alps, the illumination of morning light, and the religious cycle of conviction and awakening.

But we may be surprised by what Spring means to Dickinson and how she used it in her poetry during the year of 1862, a year of extremes: in the aftermath of her “terror” in the Fall of 1861, the death of Frazar Stearns in the War in March 1862, and her decision in April of 1862 to reach out as a poet to Thomas Wentworth Higginson.

“Your general loves you”

INTERNATIONAL NEWS

“A serious misunderstanding has occurred among the allied powers in Mexico,” as the British and Spanish return home, while the French increase their forces in Mexico. The American papers speculate that France and Spain had a falling out about how to properly handle the legislation in Mexico, and they abandoned their previous plan to install a foreign Archduke there.

The news of the capture of Fort Donelson reached England, resulting in a “considerable rise in American stocks” and general congratulations.

The Italian ministry reshuffles, due to the “Roman question”—the dispute over the temporal power of popes ruling a civil entity in Italy during the “Risorgimento,” the unification of Italy. For now, the question remains unresolved because the new Premier would like to keep Napoleonic France as an ally, and pushing the issue would likely upset the country and conflict with France’s future policy on the matter.

A series of small rebellions trouble the Ottoman Empire both in Greece and Turkey. Restless with prolonged foreign rule, decline of the empire, religious reform, and general dislike of the oppressive government, parts of Greece rebel. In Turkey, the same sentiments run wild, and parallel rebellions occur all over the country and its Asiatic territories. The Springfield Republican comments, “with troubles abroad and brawls at home, Turkey is in hot water all the time, and the numerous insurrections throughout the territory seem to threaten her with immediate dissolution.” Not too far off the mark: the nearly six-hundred-year-old empire was experiencing a hard decline due to modernization and would fall in around eighty years.

NATIONAL NEWS

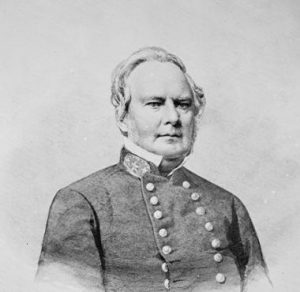

Springfield Republican, Review of the Week: Progress of the War. “The progress of the Union army is still onward, and the record of the week is as brilliant as any that has preceded it.” The Confederate forces continue to retreat, fleeing northern Virginia. News of General Burnside’s capture of New Bern, North Carolina, reaches the papers, which tell how “our men bore themselves like veterans” in the “severe fight” leading up to the capture. This capture proves crucial, as it allows the Union to reach North Carolina’s capital and occupy the coastal railroad running through the South. The Union also has “all eastern Florida” and multiple coastal points along the East Coast.

General McClellan’s “grand army” advances towards Richmond, Virginia, the capital of the Confederacy, and the Springfield Republican speculates that “the capture of Richmond cannot be many days distant.” In reality, Richmond would not fall until April 5, 1865, and this attempt to capture the city would result in a five-month long campaign leading up to the Seven Days Battles in July of this year, where the Confederacy would successfully protect Richmond.

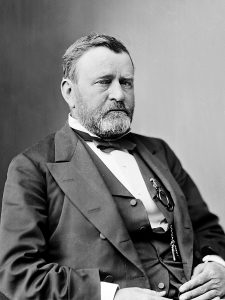

From Washington. This article reports on the controversy around General McClellan stirring up the country.

McClellan’s fall and winter campaigns ended in mistakes and failures, and one instance where the South successfully deceived the general and managed to escape from his grasp. The country is divided over the competence of McClellan, most saying that the general cannot continue to lead a regiment and needs to be replaced. However, the Republican’s author argues McClellan “is to have one more opportunity at any rate,” but nothing more.

General McClellan “is at home among his troops, and to a great extent is popular among them,” but it remains a question whether or not the general is competent, or if his appointment was purely political.

In other news, emancipation continues to be controversial in the Senate. The paper assures the reader that the bill would pass, “if it can ever come to a vote.”

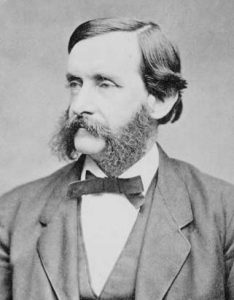

The paper also reports on abolitionist orator Wendell Phillips’s tour through Washington, and his lectures. The capital received him well, the column reports, and says, “this is in itself almost a miracle, and will be set down as an ‘event’ when the history of these times comes to be written.” Later this week, on March 24 in Cincinnati, Ohio, the orator would be booed off stage and pelted with rocks and eggs at his suggestion of fighting a war to free the slaves.

A Bit of Secret History. An 1861 letter from former Florida Senator Yulee to a correspondent from Tallahassee named Joseph Finegan was recently found.

It reveals a secret meeting of the Southern Senators, and a part of the letter is quoted in the paper:

The idea of the meeting was that the states should go out at once, and provide for the early organization of a confederate government not later than the 15th of February. This time is allowed to enable Louisiana and Texas to participate. It seemed to be the opinion that if we left here, force, loan and volunteer bills might be passed, which would put Mr. Lincoln in immediate condition for hostilities; whereas, if by remaining in our places until the 4th of March, it is thought we can keep the hands of Mr. Buchanan tied, and disable the republicans from affecting any legislation which will strengthen the hands of the incoming administration.

The senators and states did in fact go through with this plan, and Northern newspapers now have no problem calling treason on these former senators.

Letter from the Owner of “Old Glory.” William Driver, a sea captain and Union sympathizer living in Nashville, owns the original “Old Glory” flag that became famous after his merchant ship traveled the world and saved five other American crews from ruin. Many armed and unarmed attempts to seize the flag during the Civil War led Driver to hide it safely away until Nashville fell in February, when Driver took it to the Union generals and requested it to be flown over the city in triumph. The Springfield Republican publishes a letter from him to his daughter, chronicling his feelings after seeing the flag flown over the city.

From the Potomac: Proclamation by Gen McClellan. General McClellan issues a proclamation to the armies of the Potomac, addressing his decision not to take on the Potomac Blockade in the winter, which earned him criticism and contributed to the controversy around him and his competency as a general:

you were to be disciplined, armed and instructed. The formidable artillery you now have, had to be created, other armies were to move and accomplish certain results. I have held you back that you might give the death blow to the rebellion that has distracted our once happy country.

The general announces the end to the waiting period, and pleads

in whatever direction you may move, however strange my actions may appear to you, ever bear in mind that my fate is linked with yours, and that all I do is to bring you where I know you wish to be, on the decisive battle field… you know that your general loves you from the depths of his heart.

“Early Soldier-heart”

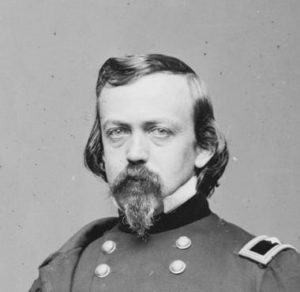

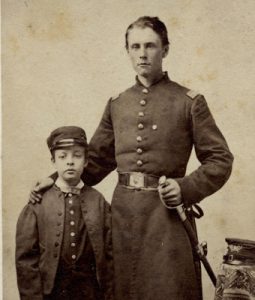

This week, Dickinson, her family, and all of Amherst dealt with the aftermath of Frazar Stearns’s death, marked by his funeral on March 22.

Amherst, March 21: In the Express: A telegram was received at 2 P.M. on Tuesday, announcing that Lieut. Fred Sanderson was returning with [Frazar Stearns’s] body … His body arrived here on Wednesday in charge of Lieut. Sanderson, and the funeral will take place on Saturday [tomorrow], at 1 ½ o’clock, in the village Church.

March 22: Dickinson writes to Louise and Frances Norcross:

He went to sleep from the village church. Crowds came to tell him good-night, choirs sang to him, pastors told him how brave he was—early soldier-heart. And the family bowed their heads, as the reeds the wind shakes.

See the full letter and account in last week’s post.

We don't know exactly when Dickinson composed the following poem, which she included in Fascicle 19, but it was likely prompted by Stearns’s death and uses phrases from the letters she wrote to her Norcross cousins and Samuel Bowles about it, quoted in full last week. It is significant that in those letters and here again, Dickinson refers to the death as “murder.”

It dont sound so terrible -

quite – as it did -

I run it over – "Dead", Brain -

"Dead".

Put it in Latin – left of my school -

Seems it dont shriek so – under rule.

Turn it, a little – full in the face

A Trouble looks bitterest -

Shift it – just -

Say "When Tomorrow comes this

way -

I shall have waded down one Day".

I suppose it will interrupt me

some

Till I get accustomed – but

then the Tomb

Like other new Things – shows

largest – then -

And smaller, by Habit -

It's shrewder then

Put the Thought in

advance – a Year -

How like "a fit" – then -

Murder – wear!

Reflection

Sharon Barnes

Spring Equinox, 2018: The aconites are in bloom in Toledo, Ohio.

When I was in 8th grade, my one year of Catholic grade school, Mr. Sarasin, my homeroom teacher, made us memorize a poem by Emily Dickinson, right down to the punctuation. Not surprisingly, it was a poem about how sure she was that heaven existed! (“I never saw a Moor” [F800A, J1052]). I was uninterested, and nobody was asking about the variety of heavens present in her work.

When I was in 8th grade, my one year of Catholic grade school, Mr. Sarasin, my homeroom teacher, made us memorize a poem by Emily Dickinson, right down to the punctuation. Not surprisingly, it was a poem about how sure she was that heaven existed! (“I never saw a Moor” [F800A, J1052]). I was uninterested, and nobody was asking about the variety of heavens present in her work.

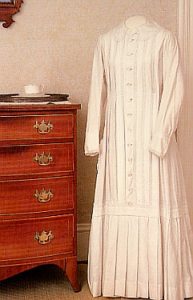

When I matriculated to a small Catholic liberal arts college in Michigan in the 1980s, the nun who I now feel sure was a lesbian, who taught us grammar using what we imagined was a holster of colored pens attached to her hip, performed a cloying Dickinson for campus poetry events, acting uncharacteristically shy in a white tatted lace collar. I remained uninterested, and a little creeped out.

Imagine my surprise a handful of years later in graduate school when I rediscovered Dickinson and found her wild paganism ranging across the pages. I was interested indeed. In a pleasurable side-by-side morning reading of Whitman and Dickinson with my partner, we paired days of poetry with selections from Open Me Carefully, and frequently howled “Sue!” at each erotic gesture we encountered thereafter. We abandoned Whitman in time, preferring Dickinson’s challenging, rewarding, sometimes impenetrable lines.

The analysis of Barton Levi St. Armand and Rebecca Patterson presented in this week’s blog confirms my young pagan heart’s response to Dickinson’s work; nature is symbolic, mystical, mythical, and catholic in that other sense: universal, wide-ranging, and all-embracing. Presented here for us to see, to notice, to breathe in and embrace, nature in Dickinson’s hand is a supreme teacher of humanity’s place in the natural order.

The analysis of Barton Levi St. Armand and Rebecca Patterson presented in this week’s blog confirms my young pagan heart’s response to Dickinson’s work; nature is symbolic, mystical, mythical, and catholic in that other sense: universal, wide-ranging, and all-embracing. Presented here for us to see, to notice, to breathe in and embrace, nature in Dickinson’s hand is a supreme teacher of humanity’s place in the natural order.

For me, the Morning in F246A, J232, that “Happy thing” who believes herself “supremer,” “Raised,” and “Ethereal,” but who flutters and staggers as her dews give way to the sun’s hot rays, is an affirmation of nature’s endless cycle and of humanity’s hubris in thinking we are here to use the earth “for meat,” as some versions of the Christian Bible say. “So dawn goes down to day,” (Robert Frost, “Nothing Gold Can Stay”) like a spring flower that wilts in the heat of the sun, so Spring will yield to Summer, and the crown of dewdrops will give way to the one bloom, her unanointed flower. So, too, humanity’s hubris about our place in nature will always be challenged by the cycle of death and birth presented in this poem and in this time of year. We too will eventually flutter and stagger.

Professor Schweitzer reminds us again this week that Dickinson was not removed from the social and cultural contexts surrounding her, the Civil War. In the midst of a March surely as full of aconites, snowdrops, and crocuses as ours are, Dickinson and the members of her community were grieving the life of Frazar Stearns, a young soldier returned home from the war for burial. And we, too, grieve the loss of young lives, in school shootings, in preventable deprivation, in what can feel like endless wars, as we note Professor Schweitzer’s convincing discussion of Dickinson’s use of the word “Murder.”

Here at the Spring Equinox, where light and dark are in perfect balance, we begin to head into the lengthening of days, the Happy Morning where all Life would be Spring. All too soon, though, the solstice will be here, and the shadows will begin to overtake the Sun King’s haughty presence in the orchard as he makes his retreat.

But for now, let us enjoy the light and the Sun’s gentle touch. Happy Spring!

Bio: Sharon Barnes is an Associate Professor and Interim Chair of the Department of Women’s and Gender Studies at the University of Toledo in Toledo, Ohio, who recently completed committing Adrienne Rich’s “Diving Into the Wreck” to memory, a highly recommended exercise.

Sources

Overview

- Emerson, Ralph Waldo. The Complete Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson. vol. 1:17.

- Patterson, Rebecca. Emily Dickinson’s Imagery. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1979, 181.

- St. Armand, Barton Levi. Emily Dickinson and Her Culture: The Soul’s Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984, 277-8, 317.

History

- Springfield Republican, volume 89, no. 13. Saturday, March 22, 1862.

- “Wendall Phillips booed in Cincinnati.” This Day in History: March 24.

- The Roman Question, Wikipedia.

- Seven Days Battles, Wikipedia.

- Old Glory, Wikipedia.

Biography

-

Leyda, Jay. The Years and Hours of Emily Dickinson. vol. 2. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1960, 49.

=