Exploring Dickinson’s literary foremother, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, two weeks ago reminds us of the importance of mothers more generally in the poet's life. We recall Virginia Woolf’s famous comment in A Room of One’s Own, “For we think back through our mothers if we are women.” Then, a column in this week’s Springfield Republican for 1862 on “The Influence of Mothers” contextualized motherhood in Dickinson’s historical moment. The nineteenth-century US idealized motherhood as a sacred duty to nurture and spiritually uplift, to be a self-less, shining beacon in a rapidly changing and war-torn world. All of this suggested this week’s focus on Dickinson’s “mothers.”

Exploring Dickinson’s literary foremother, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, two weeks ago reminds us of the importance of mothers more generally in the poet's life. We recall Virginia Woolf’s famous comment in A Room of One’s Own, “For we think back through our mothers if we are women.” Then, a column in this week’s Springfield Republican for 1862 on “The Influence of Mothers” contextualized motherhood in Dickinson’s historical moment. The nineteenth-century US idealized motherhood as a sacred duty to nurture and spiritually uplift, to be a self-less, shining beacon in a rapidly changing and war-torn world. All of this suggested this week’s focus on Dickinson’s “mothers.”

We use the plural to indicate mothering in a broad sense. Dickinson's biological mother, Emily Norcross (1804-1882), was a disappointing figure for most of her daughter’s life. There is evidence in Dickinson’s writings that she felt “motherless.” Most of the poems she wrote containing the word “mother” are about “Mother Nature” or “Mother Eve.”

But there is also evidence that she found a mother figure in the woman who was one of her closest friends throughout her adult life, Elizabeth Luna Chapin Holland (1823- 1896). In a move to perhaps divert attention from her emotional dependence, Dickinson called Holland “Little Sister,” despite the fact that Holland was seven years her senior. By all accounts, Holland perfectly exemplified the Victorian mother, who excelled in the domestic sphere of nurturing and support. This week, we explore Dickinson’s relationships with her mothers and with the theme of mothering through her poetry and letters.

“The Influence of Mothers”

Springfield Republican, June 28, 1862

Progress of the War, page 1

“We have again reached a moment of silent and anxious suspense. Gen. McClellan has crowded the rebel lines close up to Richmond, and there can be no further advance without a great battle, unless the enemy abandon the position, which is not probable. Everything is ready on our side, the last parallel is completed, the siege guns are in position, and probably before what we write is printed the country will be startled with news of the most terrific battle yet fought. If our arms are successful, as we confidently expect, the war is substantially at an end; if otherwise the struggle will be still further prolonged, and we may be embarrassed by foreign intervention. Everything depends on success at Richmond.”

The Emancipation Bill, page 2

“The bill to free the slaves of rebels that passed the House on Tuesday provides for the emancipation of the slaves of all persons holding civil or military office in the confederacy after the bill becomes a law, and of all others who shall not return to their loyalty within sixty days after a proclamation to that effect to be issued by the president. The bill also disqualifies all the classes named from ever holding office under the United States government. The president is authorized to negotiate for the acquisition, by treaty or otherwise, of lands or countries in Mexico, Central America or South America, or in the islands in the Gulf of Mexico, or for the right of settlement upon the lands of said countries for all persons liberated under this act, to be removed with their own consent.”

Western Virginia, page 2

“Two bills are before Congress for the admission of Western Virginia as a state into the Union.”

Influence of Mothers, page 6

“Love as we may other women, there stands first and ineffaceable the love of ‘mother;’ gaze as we may on other faces, our mother’s face is still the fairest; bend as we shall to other influence, still overall silent but mighty, reaching to us from long gone years, is a mother’s influence. In scenes of sin and shame and license come that pure, that holy, that ever-loving presence.”

The Power of Music by Augusta B. Garrett, page 6

“It happened one day that the evil ones were all assembled together. They issued from hell to conquer the souls through all the earth. Lucifer left the minstrel to take care of the infernal regions and promised, if he let no souls escape, to treat him on his return with a fat monk, roasted, or a usurer, dressed with hot sauce. But, while the fiends were away, Saint Peter came in disguise, and allured the minstrel to play at dice, who, for lack of money, was so imprudent as to stake the souls which were left under his care. They were all lost and carried off by St. Peter in triumph. The devil returned, found hell empty and the fires out, and very unceremoniously sent the minstrel away; but he was generously received by St. Peter. Lucifer, in his wrath, threatened with severe punishment any fiend who should again bring there a minstrel’s soul; and thus, they ever after escaped the claws of the evil one.”

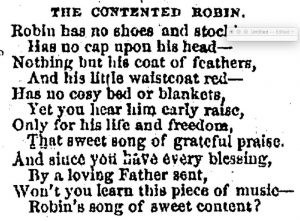

Poetry, page 7

Books, Authors and Art, page 7

Books, Authors and Art, page 7

“A monthly magazine for business men is published in Philadelphia, with the title of the American Exchange and Review. But it must be true that businessmen are slower than their wives and daughters, for side-by-side with the American Exchange for June lie the fashionable monthlies of Godey and Peterson for July. It will be a great convenience to the ladies to receive these numbers in advance of the date.”

Hampshire Gazette, July 1, 1862

The Crops, page 1

“Vegetation of all kinds was never more promising at this season of the year than it now is in this region.”

Influence of Women in Secessia, page 1

“Secession went in among the daughters of the South just as a contagious disease would, or a new style of bonnet. It wasn’t urged into them. They took it. They liked it. It made the amiable angry, the sweet sour, the attractive repulsive, the handsome ugly as sin. It made havoc of all female charms and graces. It muddled the female moral sense and sense of honor. You can’t answer or argue with a woman. There is but one weapon left us in combat with these secesh: their own—insult. General Butler was right in using it.”

page 2

“The rumor of a repulse of our forces before Charleston, first announced from rebel sources, proves too true. Reinforcements will be needed in considerable numbers before the city can be captured.”

Amherst, page 3

“Col. W. S. Clark arrived in town Wednesday evening. Notwithstanding the pouring rain, a large number of citizens turned out to welcome him, and he was received at the depot with three times three rousing cheers. His stay will not be long. The rebels are to be whipped and he means to have a hand in it. The ladies of Amherst are busily engaged in procuring articles for the comfort of our wounded soldiers.”

“I Never Had a Mother”

In his first letter, Thomas Wentworth Higginson asked Dickinson about her “companions,” and she replied:

Hills – Sir – and the Sundown – and a Dog – large as myself, that my Father bought me – They are better than Beings – because they know – but do not tell – and the noise in the Pool, at Noon – excels my Piano. I have a Brother and Sister – My Mother does not care for thought –and Father, too busy with his Briefs – to notice what we do – (L 261, April 25, 1862)

Notably, and probably with some posing, Dickinson mentions first the “hills” (the rolling Holyoke range is quite distinctive and beautiful), sunsets, and her dog Carlo. Rather far down the list is her mother, who, Dickinson notes acerbically, does not share her interest in thinking. Dickinson amplified this sense of separation from her mother in a comment she made to Higginson on his first visit to her in 1870, which he reported to his wife in a letter dated 16 August 1870. He was taken aback to hear her say:

I never had a mother. I supposed a mother is one to whom you hurry when you are troubled (L342).

Sharon Leiter notes that in an 1874 letter to Higginson, Dickinson developed this theme of motherlessness:

I always ran Home to Awe when a child, if anything befell me. He was an awful Mother, but I liked him better than none (L405).

Leiter wonders whether Dickinson was exaggerating or pointing to a “fundamental reality of her emotional life,” and cites, with some qualification, John Cody’s reductive (and heteronormative) psychoanalytic reading that because of her mother’s weakness and distance, “Dickinson failed to make a proper female identification and identified with the males in her life,” preventing her from having a satisfying sex life (how does he know that?).

After her mother’s death in 1882, however, Dickinson wrote to her friend and mother-figure Elizabeth Holland, confessing the deep connection that finally developed with the woman who was her mother:

We were never intimate Mother and Children while she was our Mother–but Mines in the same Ground meet by tunneling and when she became our Child, the Affection came (L792, mid-Dec 1882).

In late October 1885 Dickinson wrote to console a friend who had lost her mother by saying,

Who could be motherless who has a Mother’s Grave within confiding reach? Let me enclose the tenderness which is born of bereavement. To have had a Mother – how mighty! (L1022).

Despite all the research on Emily Norcross Dickinson, we know almost nothing about her inner life because she apparently hated writing letters (it became a family joke). She was the eldest of two daughters in a large prosperous family from Monson, twenty miles south of Amherst, and had an unusually good education, attending the Monson Academy and then a year at a noted girls’ boarding school in New Haven, CT. She met Edward Dickinson in 1826, and after a lopsided correspondence (he wrote around seventy letters to her, she responded with around twenty) and much ambivalence on her part about leaving her close-knit family, they married on May 6, 1828.

Emily Norcross had three children over the next five years and ran her household in exemplary (or fanatical, according to Dickinson) fashion without servants for many years. She excelled in cooking, attended social and community events, and was the first in the family to convert in 1831. She was a skillful gardener, a passion she passed on to her daughter. She loved roses in particular, and grew figs, a difficult feat in New England.

Lavinia describes her mother as tender and loving, but others recall her as timorous and fearful, especially when her husband’s business and duties took him away from home. Both she and Dickinson suffered a bout of depression when they moved back to the Homestead in 1855, but Dickinson complained to Elizabeth Holland that her mother’s prostration took precedence (L 182). The domestic and caretaking duties that fell to Dickinson at that time might have contributed to her gradual withdrawal from society. In 1874, a year after her husband’s sudden death, Emily Norcross suffered a stroke and for the last four years of her life needed full time care, which largely fell to Dickinson, who died only four years after her mother. About their relationship, which some have dismissed as unimportant, biographer Richard Sewall concludes:

Emily learned from her what was perhaps more valuable than anything a brilliant mother could have given her: some lessons in simple, devoted humanity, important for a precocious girl not disinclined to the Dickinson snobbery and the satiric Dickinson wit.

The woman Dickinson looked to for maternal emotional support was Elizabeth Luna Chapin Holland, wife of Josiah Holland, the literary editor and part owner of the Springfield Republican and friend of Samuel Bowles. Dickinson met the Hollands in 1853 when they attended one of the famous Commencement Week dinners put on by the Dickinsons. The Hollands epitomized the Victorian ideal of marriage; Josiah was large, imposing and intellectual, and Elizabeth was small, doting and warm-hearted.

Dickinson was so pleased with these new friends that she and Lavinia visited the Hollands’ home in Springfield, MA in Fall 1853 and again in Fall 1854. Their welcoming and vibrant household was the antithesis of the strict and dour Dickinson home, and despite Josiah’s anti-feminism, he rejected religious orthodoxy and had a strong commitment to the literary world, both of which Dickinson shared. And he genuinely cared for Dickinson. For example, as we detailed in the post on Elizabeth Barrett Browning, although he critiqued Barrett Browning's work as morally questionable, we know from Higginson’s report of his visit to Amherst that Josiah gave Dickinson a picture of Mrs. Browning’s tomb, obviously honoring his friend's delight in this woman writer and literary role model (note on L342).

Reflection

Marianne Hirsch

“Matrophobia,” Adrienne Rich wrote in the 1970’s, is not fear of mothers, but “fear of becoming one’s mother.” Hers is a diagnosis that describes many women writers over the centuries, even those who are not feminists. Casting their mothers as “angels in the house,” to use Virginia Woolf’s derogatory term, they tend to cast themselves as motherless daughters who can rewrite the scripts of dailiness and of femininity. When Rich later writes about Jane Eyre and about her strength and the strength of her writing voice, she alludes to Jane’s motherlessness – a motherlessness that is full of temptations she must evade, but that nevertheless enables her survival, her development, and, indeed, the new script she forges for herself. But Rich also makes sure to tell us that Jane is not unmothered. She relies on surrogate mothers – her teacher, her friend, her cousins, the moon – to sustain and to protect her.

“Matrophobia,” Adrienne Rich wrote in the 1970’s, is not fear of mothers, but “fear of becoming one’s mother.” Hers is a diagnosis that describes many women writers over the centuries, even those who are not feminists. Casting their mothers as “angels in the house,” to use Virginia Woolf’s derogatory term, they tend to cast themselves as motherless daughters who can rewrite the scripts of dailiness and of femininity. When Rich later writes about Jane Eyre and about her strength and the strength of her writing voice, she alludes to Jane’s motherlessness – a motherlessness that is full of temptations she must evade, but that nevertheless enables her survival, her development, and, indeed, the new script she forges for herself. But Rich also makes sure to tell us that Jane is not unmothered. She relies on surrogate mothers – her teacher, her friend, her cousins, the moon – to sustain and to protect her.

It is thus not a surprise that Emily Dickinson – the supreme crafter of her very own script—should distance her writing self from her mother, nor that she should describe her mother as someone who does not “care for thought” in the ways she herself does. Thinking women leave their mothers behind; they identify with fathers, or with women outside the family, with those who do not pose the dangers of matrophobia. Dickinson’s companions are nature, dogs, friends. Neither is it a surprise, however, that Dickinson turns to her mother during her illness and after her death. “To have had a mother,” she writes, “how mighty.” The stress is on the finality of the “have had.” The mother is in the past tense.

Yet Dickinson spends years caring for her mother in her illness and dies a short four years after her mother’s death. If she claims her in her death, does she repair the rift she nurtured in her life? Is the moving elegy she writes, “To the bright east she flies,” actually dedicated to Emily Norcross Dickinson, or is it more about a primal maternal loss, one that faces us all – one that leaves us “homeless at home?”

Dickinson’s ambivalent relationship to her mother is familiar for anyone who studies women writers. The mother who is alive poses the threat of matrophobia, but the dead mother, no longer threatening, invites a reconsideration. Virginia Woolf waited nearly three decades before writing To the Lighthouse (1927), the book that enabled her to work through the premature loss of her mother, Julia Stephen. She stated that writing the book did for her “what psychoanalysts do for their patients.” Dickinson’s elegy, and the other poems included here, are less specific and they engage the mother as figure and not as person. They do not ultimately negate the poet’s statement that “I never had a mother.”

bio: Marianne Hirsch is William Peterfield Trent Professor of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University and Professor in the Institute for Research on Women, Gender, and Sexuality. She is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and a former President of the Modern Language Association of America. She was born in Romania, and educated at Brown University where she received her BA/MA and Ph.D. degrees.

Hirsch’s work combines feminist theory with memory studies, particularly the transmission of memories of violence across generations. Among many other works, she is the author of The Mother/Daughter Plot: Narrative, Psychoanalysis, Feminism (1989).

Sources

Overview

Plant, Rebecca Jo. Mom: The Transformation of Motherhood in Modern America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010.

Woolf, Virginia. A Room of One’s Own. (1929). University of Adelaide, Chapter Four.

History

Hampshire Gazette, July 1, 1862

Springfield Republican, June 28, 1862

Biography

Dickinson, Emily. The Letters of Emily Dickinson. Eds. Thomas Johnson and Theodora Ward. 3 vols. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1958.

Leiter, Sharon. Critical Companion to Emily Dickinson: A Literary Reference to her Life and Work. New York: Facts on File, 2007, 278-81, 325-38.

Sewall, Richard. The Life of Emily Dickinson. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1980, 88.