“Comet Swift-Tuttle”

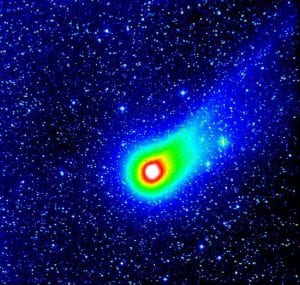

Comet Swift-Tuttle, captured by astronomer Jim Scotti of the University of Arizona's Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, through a Spacewatch telescope at Kitt Peak on Nov. 24, 1992 during the comet's last close approach to Earth.

Comet Swift-Tuttle, captured by astronomer Jim Scotti of the University of Arizona’s Lunar and Planetary Laboratory through a Spacewatch telescope at Kitt Peak on Nov. 24, 1992 during the comet’s last close approach to Earth.[/caption]

This week, we take our cue from the Springfield Republican for July 13, 1862, which reported the sighting in New England of what would eventually be called the Comet Swift–Tuttle. A ball of ice, dust, and debris with a nucleus 16 miles wide, this comet is notable because, though it only passes by Earth every 133 years, its constituent debris creates the Perseid meteor shower every year when Earth moves through the trail of its orbit. This spectacular display was first seen in 1862, a particularly active year for comets.

Two astronomers discovered this comet independently in the following week: Lewis Swift on July 16, 1862 and Horace Parnell Tuttle on July 19, 1862. These kinds of astronomical discoveries were big news in the nineteenth century, which was a period of enormous expansion and growing popularity of the field of astronomy. Developments in optical technology led to advancements in telescopes and photography and were abetted by new concepts about the origins of the universe, the speed of light, and expanded ability to do calculations. The nineteenth century saw the discovery of 36 asteroids, four satellites, a planet—Neptune, a new ring around Saturn, and several comets, including the Swift-Tuttle Comet.

Although Dickinson does not mention this sighting, biographer Richard Sewall notes how frequently Dickinson uses astronomical language, references, and motifs in her writing. We know Dickinson studied astronomy as one of her subjects at both Amherst Academy and Mount Holyoke Female Seminary in the 1840s. She not only mentions planets, heavenly bodies, and constellations in her writing but knowledgeably references astronomical phenomena like eclipses, angular measurement, and solstices. Scholars who study these references find that Dickinson had a deep engagement with astronomy and that her very conception of poetry is astronomical: Brad Ricca claims that

Dickinson uses poetry as a sextant,

an instrument for celestial navigation that measures the angular distance between an astronomical object and the horizon. This means of finding one’s way or connecting two points “slantwise” conforms to Dickinson’s recommendation to “Tell all the truth/ but tell it slant” (F 1263A, J1129) .

This week, we explore why Dickinson turned often to astronomy and found it so hospitable to her metaphorical imagination. One explanation is that the “new sciences” of this period were radically challenging older conceptions of the world and Dickinson wanted to participate in these exhilarating new ideas. Specifically, Dickinson’s engagement with astronomy occurred at the moment of a decisive shift away from religious explanations of science. Astronomy allowed her to focus on the universe, on perception and cognition, and explore the limits of scientific knowledge. It would also have a staggering personal effect on members of her family.

“The Waning of the Comet”

Springfield Republican, July 13, 1862

Review of the Week, page 1

“Doubt and hesitation are at an end. Congress, the executive, the patriot army and the people are ready, and the first crash of the grand onset which is to overwhelm the gigantic and infamous rebellion of 1861 now begins.”

The Waning of the Comet, page 2

“The comet that flashed so suddenly upon our vision a week and a half ago, is now visibly seen on the wane, and will soon be out of sight, lost among the constellations of the north. It has been in view just long enough to convince the astronomers that their knowledge is not infallible, and to furnish fireworks for the millions on the evening of the 4th, and now it leaves as suddenly as it came. It seems smaller and less bright from night to night, and it will soon be invisible to the naked eye. Then it will rapidly fade from the sight of the telescope, and be gone, probably never again to be seen by this generation.”

Great Battle in Missouri Recalled, page 4

“On the morning of the 5th, [1861] Col. Siegel attacked a body of 6,000 rebels about seven miles east of Carthage on a prairie. Col. Siegel began the attack at 9:30 a.m., breaking the enemy’s center twice. After an hour and a half of fighting, he silenced their artillery.”

Literary Anniversaries: Amherst College, page 5

“Notwithstanding the absence of strangers and the presence of the heat, a large and intelligent audience assembled in the village church Sunday afternoon to listen to the Baccalaureate Sermon by President Stearns, founded on Revelations XXI:7— ‘He that overcometh shall inherit all things.’”

Hampshire Gazette, July 15, 1862

Amherst, page 3

“In the afternoon of Wednesday, Henry Ward Beecher addressed the literary societies. He said it might be expected, perhaps, that he would choose a literary subject, but we are so near the edge of revolution that public questions must take the precedence.”

“Astronomy is a Science which has, in all Ages, Engaged the Attention of the Poet, the Philosopher, and the Divine”

As mentioned in the Overview, astronomy became increasingly popular during the nineteenth century but also experienced a decisive shift. It was a subject on the curriculum at Amherst Academy and Mount Holyoke Female Seminary when Dickinson studied there in the 1840s. The Dickinson family library included several books about astronomy, including Felix Eberty’s Stars and the Earth (1854) and Denison Olmsted’s Introduction to Astronomy (1861). Eleanor Heginbotham notes that Elijah H. Burritt’s Geography of the Heavens and Class Book of Astronomy (1838), a textbook used at Amherst Academy, linked the study of astronomy directly to Dickinson’s art. Burritt announced:

Astronomy is a science which has, in all ages, engaged the attention of the poet, the philosopher, and the divine.

Astronomy also became a field in which women could and did excel. In 1839, William Mitchell and his daughter Maria observed Halley’s comet from their observatory on Nantucket, off Cape Cod. In 1847, Maria Mitchell discovered a comet on her own, which was named for her, and received a medal for her discovery from King Frederick VI of Denmark, which earned her international recognition and gave needed status to American astronomy. Mitchel was the first woman to be a professional astronomer. She was appointed professor of astronomy at Vassar College, director of the Vassar College Observatory and, with much fanfare, became the first woman elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1848.

Dickinson’s exposure to astronomy was largely thanks to Edward Hitchcock, Professor of Geology and Theology at Amherst College and author of The Religion of Geology (1851), a book also in the Dickinson family library. An eminent “geological theologian,” as he called himself, Hitchcock influenced the curriculum at both schools Dickinson attended. Although Hitchcock avidly embraced new scientific discoveries and encouraged an attitude of wonder, he supported the position, prevalent in the early part of the century, that sciences like astronomy and geology confirmed the existence of God and were compatible with Christian theology.

At Mount Holyoke Seminary, Dickinson used the textbook Compendium of Astronomy (1839) by Olmsted, which supported such a view. But after the publication in 1859 of Charles Darwin’s On the Origins of Species, which was reviewed favorably by Asa Gray in the Atlantic Monthly in 1860, scientific discoveries began to have a destabilizing effect on religious belief and signaled the beginning of a decisive shift away from a teleological trend in scientific thought. Joan Kirkby notes:

Between 1859 and 1873, New England was “the main battle-ground” of the confrontation between science and theology. … Emily Dickinson herself was imbricated in a unique web of affiliation with Darwin and darwinian ideas; the key New England figures in this debate were all known to Dickinson either through her family, her schooling, her library or the libraries at Amherst Academy and Mount Holyoke, or through the pages of the New England periodicals to which the Dickinsons subscribed.

Dickinson, too, was swept up in the excitement about the changing view of the world, though Sabine Sielke argues that Dickinson’s

take on science is critical and engaged rather than positivist and affirmative.

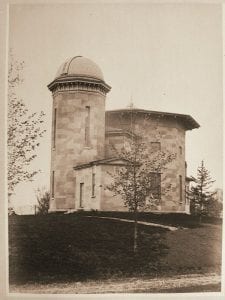

While astronomy was an important element in Dickinson’s intellectual world, we could also argue that it had a devastating effect on Dickinson’s family. One of the consequences of astronomy’s increasing popularity was the building of observatories; more than 170 were built across the country in the nineteenth century. This included the Lawrence Observatory at Amherst College, built in 1847. The addition of a larger telescope in 1854 helped the Lawrence Observatory build a reputation for innovation. And this reputation attracted more students, which required more faculty.

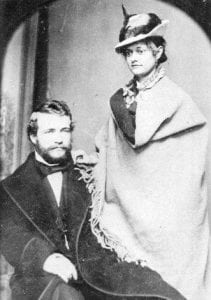

In 1881, a young academic named David Peck Todd was hired as an assistant Professor of Astronomy at Amherst College and brought along his young wife, Mabel Loomis Todd. Mabel assisted David with his work, traveling with him to Japan to see a total eclipse in August 1896 and writing a book about it titled Corona and Coronet. Her importance to this story lies in her affair during the 1880’s with Austin Dickinson, many years her senior, which led to the bitter divide between the Dickinson families that would prevent the publication of a “complete works” of Dickinson's poetry until Thomas Johnson’s edition in 1955. In 1890, Mabel began co-editing Dickinson’s poetry, with Thomas Higginson. The same year Mabel brought out a collection of Dickinson’s letters, she published Total Eclipses of the Sun, a survey of the history, science and characteristics of eclipses with a poetic epigraph from Dickinson (included in our Poems for this week).

Reflection

Ivy Schweitzer

Planetarium

Thinking of Caroline Herschel (1750—1848)

astronomer, sister of William; and others.

What we see, we see / and seeing is changing …

Sources

Overview

Ricca, Brad. “Emily Dickinson: Learn’d Astronomer.” Emily Dickinson Journal 9.2 (Fall 2000): 96-109, 103.

Sewall, Richard. The Life of Emily Dickinson. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1980, 354.

Sielke, Sabine. “Natural Sciences.” Emily Dickinson in Context. Ed. Eliza Richards. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013, 236-245.

Williams, Sharone E. “Astronomy.” All Things Dickinson: An Encyclopedia of Emily Dickinson’s World. Ed. Wendy Martin. 2 vols. Santa Barbara: Greenwood: 2014, 55-59.

History

Hampshire Gazette, July 15, 1862.

Springfield Republican, July 13, 1862

Biography

Heginbotham, Eleanor. “Reading in the Dickinson Libraries.” Emily Dickinson in Context. Ed. Eliza Richards. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013, 25-35 29.

Kirkby, Joan. “[W]e thought Darwin had thrown ‘the Redeemer’ away’: Darwinizing with Emily Dickinson.” Emily Dickinson Journal 19, 1, 2010: 1-29, 7.

Sielke, Sabine. “Natural Sciences.” Emily Dickinson in Context. Ed. Eliza Richards. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013, 236-245, 237.

"Why an Eclipse Can Only Last Eight Minutes, by Mabel Loomis Todd." New England Historical Society.

Williams, Sharone E. “Astronomy.” All Things Dickinson: An Encyclopedia of Emily Dickinson’s World. Ed. Wendy Martin. 2 vols. Santa Barbara: Greenwood: 2014, 55-59.

Thank you, Ivy for turning me on to this. I am enjoying it immensely.

So glad you are enjoying the blog. The post on Astronomy is particularly fascinating. Who knew??