On Choosing the Poems

Dickinson’s intense series of letters to Samuel Bowles, discussed in the Biography section, are a backdrop for the poems we have chosen on the theme of “entitle.” In Letter 250, Dickinson sends Bowles a copy of “Title divine – is mine!” a poem she wrote in 1861, but which we have chosen as the keynote poem for this week exploring a crucial topic for Dickinson: entitlement and power. She frequently explores the ideas of titles and royalty, and their inversions, as entangled with power dynamics, gender issues, questions of religious salvation, class, and love.

Every poem for this week displays some form of Dickinson’s play with entitlement. “Title divine – is mine!” suggests that the very notion of power is inseparable from religion, as nearly all of its imagery of royalty is matched with a corresponding religious modifier: “Empress, ” for instance. “For this – accepted breath -” also touches on religious royalty, but focuses on the power of nature as well, especially during the “perennial” summer months that, the poem suggests, may go on eternally.

Dickinson also thought about power in terms of ownership and being owned. Entitlement, she muses, can be a source of heavenly power, whether one is entitled or the object of entitlement, and is the only credential needed to be worthy of praise and of the highest heaven. Dickinson puts this notion into dialogue with class differences in “The court is far away,” and questions what one would have to own to be entitled, if anything at all.

“Of Bronze and Blaze” further complicates Dickinson’s ideas of power. Loneliness, legacy, and a sense of universal presence unlocks a door to having the utmost control over oneself, but the subtle “Taints of Majesty” tell us that power, entitlement, and degree are not necessarily the best things in the world, or the most notable and lasting.

“I’m ceded – I’ve stopped / being Their’s -” concludes this group as a mirror to “Title divine – is mine!” The poem, a grand declaration of independence, refuses divine power and Christianity in favor of self-baptized and self-claimed power that comes from the speaker simply speaking it into existence, becoming a source of authorization herself. This poem collapses all notions of heavenly hierarchy that “Title divine” sets up, replacing it with something anarchic in how the “half-conscious Queen” rules her kingdom.

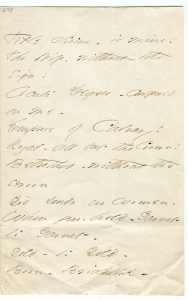

Title divine – is mine! (F194A and B, J 1072)

Title divine – is mine!

The Wife – without the

Sign!

Acute Degree – conferred

on me –

Empress of Calvary!

Royal – all but the Crown!

Betrothed – without the

swoon

God sends us Women –

When you – hold – Garnet

to Garnet –

Gold – to Gold –

Gold – to Gold –

Born – Bridalled – Shrouded –

In a Day –

“My Husband” – women

say –

Stroking the Melody –

Is this – the way?

Title divine, is mine.

The Wife without

the Sign –

Acute Degree

conferred on me –

Empress of Calvary –

Royal, all but the

Crown –

Betrothed, without

the Swoon

God gives us Women –

When You hold

Garnet to Garnet –

Gold – to Gold –

Born – Bridalled –

Shrouded –

In a Day –

Tri Victory –

“My Husband” – Women say

Stroking the Melody –

Is this the way –

EDA manuscripts: "F194A originally in Amherst – Amherst Manuscript # 678 – Emily Dickinson letter to Samuel Bowles – asc:10985 – p. 1. Courtesy of Amherst College, Amherst, MA." F194B originally sent to Susan Dickinson, 1865 in MS Am 1118.3 (361). Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. First published in Life and Letters (1924), 49-50, from the copy to Susan Dickinson (B), in twenty-one lines; also Complete Poems (1924), 176-77, and later collections. Bingham, Emily Dickinson’s Home (1955), 373, from the copy to Bowles (A)."

This is a key poem in Dickinson’s canon, and though dated to 1861, she sent it in a letter to Bowles in early 1862 with these brief words:

Here’s – what I had to “tell you”– you will tell no other? Honor – is it’s own pawn –(L250).

She would repeat that last phrase as the conclusion to her first letter to Thomas Higginson on April 15 of this year.

Strangely, Dickinson did not copy this poem into a fascicle, but sent a version to Susan Dickinson in 1865, with some key differences worth noting. Sue’s copy (B) leaves out the exclamation points after lines 1, 2, 4 and 5, the question mark at the end, and includes the phrase “Tri Victory” after “In a Day–”. The version sent to Bowles is altogether more triumphant, even ecstatic, in tone and visual form than Sue’s version, which is more restrained.

The poem is often read as a declaration of star-crossed love for one of the men in Dickinson’s life, possibly Bowles, but we offer it as a study in self-entitlement, closely related to the ecstatic declaration discussed in last week’s post, “Mine – by the right of the White Election!” (F411A, J528). These poems are connected by the repetition of the word “mine” and its rhyme, here, with “divine.” Thus, entitlement and whiteness are closely linked by their association with marriage and poetry. In this case, though, the marriage is probably not an earthly one.

The poem brings together an important cluster of images. Titles, often of royalty, that are also, often, self-conferred (like the “unannointed [sic] Blaze” of “Dare you see a Soul at the ‘White Heat’” (F 401A, J 365). Dickinson only gave titles to 24 of her poems, and those were poems she sent in letters; only three titles occur in the fascicles. The large majority of her poems go untitled, and yet the conferring of titles is a significant gesture here and in other poems, expressing a recognition of self-worth.

Related images are degree, a word that has 17 meanings in Dickinson’s Webster’s, including “proof of value,” “radius,” “longitude,” “marital status,” “honor,” and “token; symbols; coronation.” In this poem, degree is “acute,” an intensifier that suggests illness, and rhymes boldly with “me.” It also rhymes with the weighty title, “Empress of Calvary,” referring to the hill on which Jesus was executed, which becomes a metaphor Dickinson uses here and in other poems for the agony of suffering and loss. Finally, gems figure preciousness. Here, the double ceremony of holding “Garnet to Garnet–/ Gold –to Gold” formally enacts the tautological comparison of like to like, a radical equality or parity.

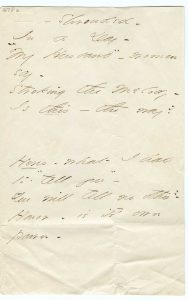

We need to note the several voices in the poem that express different, contradictory attitudes. The first boldly declares her entitlement as a divine wife, without the sign, and criticizes the current institution of marriage, in which women are “Born – Bridalled – Shrouded –/in a Day –”. By making “bridal” a passive verb, Dickinson produces a pun on the word “bridled,” a means of controlling a horse or draught animal through a metal bit in its mouth. This pun evokes the infamous “scold’s bridle,” a Medieval form of punishing unruly, garrulous women, by “branking” them.

Such language, with the implication that women are constrained and even punished by marriage, is echoed in a poem by an earlier New England poet, Lydia Huntley Sigourney. Styled “the Nightingale of Hartford,” Sigourney wrote for a living (despite her husband's disapproval) and published a poem titled “The Bride,” in which an observer of a newly married young woman chides those who would make light of this scene and casts marriage for women in terms that similarly evoke restraints placed on beasts of burden:

Mock not with mirth

A scene like this, ye laughter-loving ones;

The licens’d jester’s lip, the dancer’s heel—

What do they here? Joy, serious and sublime,

Such as doth nerve the energies of prayer,

Should swell the bosom, when a maiden’s hand,

Fill’d with life’s dewy flow’rets, girdeth on

That harness which the ministry of death

Alone unlooseth, but whose fearful power

May stamp the sentence of eternity.

At the end of “Title divine,” different women’s voices stroke with eerie possessiveness the “Melody” of the phrase “My Husband.” The voice in the final line seems to call much into question. David Porter calls the poem

a model of evasion, of language crafted to carry emotion without verifiable reference.

Sandra Gilbert concludes,

Surely this poem’s central image is almost the apotheosis of anguish converted into energy.

Helen Vendler calls this a “boast-poem,” and yet points out the absence of the first person pronoun.

Sources

Gilbert, Sandra. “The Wayward Nun beneath the Hill: Emily Dickinson and the Mysteries of Womanhood.” Feminist Critics Read Emily Dickinson. Ed. Suzanne Juhasz. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1983: 22-44.

Hallen, Cynthia, ed. Emily Dickinson Lexicon. Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University, 2007.

Leiter, Sharon. Critical Companion to Emily Dickinson: A Literary Reference to her Life and Work. New York: Facts on File, 2007.

Porter, David. Dickinson, The Modern Idiom. Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1981, 167.

Vendler, Helen. Dickinson: Selected Poems and Commentaries. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University, 2010, 60-63.

For this – accepted breath (F230B, J195)

For this – accepted Breath –

For this – accepted Breath –

Through it – compete with Death –

The fellow cannot touch this Crown –

By it – my title take –

Ah, what a royal sake

To my nescessity – stooped down!

No Wilderness – can be

Where this attendeth me –

No Desert Noon –

No fear of frost to come

Haunt the perennial bloom –

But Certain June!

Get Gabriel – to tell – the royal syllable –

Get saints – with new – unsteady tongue –

To say what trance below

Most like their glory show –

Fittest the Crown!

EDA manuscript: "Originally in Packet XV, Fascicle 9, ca. 1862. First published in Letters (1894), 216, from the Bowles copy (A); also Life and Letters (1924), 254-55; and Letters (1931), 205. Unpublished Poems (1935), 27, from the fascicle (B), as three six-line stanzas. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA."

This poem is also linked to Samuel Bowles; Dickinson sent the second stanza to him, and included the full version in Fascicle 9. It brings together a cluster of images similar to those in “Title Divine,” but without the agony: the crown, a title taken, royalty and the angel Gabriel announcing “the royal syllable.”

Although the imagery of death, saints and the angel suggests the crown is a heavenly one, the opening lines describe “accepted Breath” as competing with Death, and it is this signal of resignation to life that confers title and entitlement on the speaker. The second stanza describes the “perennial bloom” of a “Certain June” that suggests both an Eden on earth and in Heaven.

William Shurr calls this a “riddle:” what human experience is most like glory in heaven, it asks, and he finds the answer to be marriage. Shira Wolosky sees in this poem

human language invested with a power whose source remains divine.

Sources

Shurr, William. The Marriage of Emily Dickinson: A Study of the Fascicles. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1983, 23.

Wolosky, Shira. Emily Dickinson: A Voice of War. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1984, 158-59.

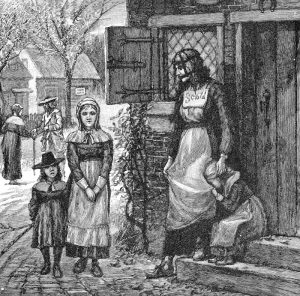

Of Bronze – and Blaze (F319A, J290)

Of Bronze – and Blaze –

Of Bronze – and Blaze –

The North – tonight –

So adequate – it forms –

So preconcerted with itself –

So distant – to alarms –

An Unconcern so sovreign

To Universe, or me –

Infects my simple spirit

With Taints of Majesty –

Till I take vaster attitudes –

And strut opon my stem –

Disdaining Men, and Oxygen,

For Arrogance of them –

My Splendors, are Menagerie –

But their Competeless Show

Will entertain the Centuries

When I, am long ago,

+An Island in dishonored

Grass –

Whom none but +Daisies, know –

+ Some + Beetles

Link to EDA manuscript: "Originally in Poems: Packet XIV, Mixed Fasciles, ca. 1860-1862. First published in Poems (1896), 133, with the alternatives not adopted. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA."

This poem takes its inspiration from a display of the Northern lights, or aurora borealis. In October 1851, Dickinson’s father Edward rang the church bells in Amherst to call attention to this rare display in the sky. Dickinson wrote about the phenomenon to her brother Austin (L53) and used the imagery of the lights in this poem and another from the same year, 1862, “Blazing in Gold – and /Quenching – in Purple” (F321, J 228). It was placed in Fascicle 13, which takes up the theme of the relation of nature and the artist, and follows “There’s a certain slant of light” (F320A, J258). Susan Leiter points out the

three major elements/realizations in the poem: the grandeur of the northern lights (nature’s immortality), the poet’s myriad splendors (her poetry’s immortality), and the “Island in dishonored grass” (her personal, physical mortality). None of the three dominates. The subtlety and brilliance of the poem lies in the way Dickinson keeps these realities in motion around one another, letting each reflect upon and modify the impact of the others.

Of note is the end of the first long stanza, where the speaker’s “simple spirit” is “infected,” with “Taints of Majesty” from the glorious sight, “And strut opon my stem–.” The pride (strutting) is balanced by the ambivalence in “infected” and “taints.” The wonderfully compressed image expresses an entitlement that is clearly qualified. Its connection to the “Daisies” of the final line links this poem to the Master documents, which were discussed in the post for January 15-21, Week 3.

Sources

Mitchell, Domhnall. “Amherst.” Emily Dickinson in Context. Ed. Eliza Richards. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013, 13-24.

Leiter, Sharon. Critical Companion to Emily Dickinson: A Literary Reference to her Life and Work. New York: Facts on File, 2007, 152-54.

The court is far away – (F250A, J235)

The Court is far away –

No Umpire – have I –

My Sovreign is offended –

To gain his grace – I’d die!

I’ll seek his royal feet –

I’ll say – Remember – King –

Thou shalt – thyself – one

day – a Child –

Implore a larger – thing –

That Empire – is of Czars –

As small – they say – as I –

Grant me – that day – the

royalty –

To intercede – for Thee –

Link to EDA manuscript: "Originally in Packet XXXVII, fascicle 10, ca. 1860-1861. First published in Bolts of Melody (1945), 164, from a transcript of A. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA."

This poem is a good example of the short hymn meter, consisting of quatrains of 6686 rhyming abcb, with 7 syllables in line 3, perhaps to indicate the offense taken and, thus, withheld, by the “Sovereign.” Is the “court” here a figure for the court of Heaven, in which God will judge those who appear? “Court” has a double meaning of royal/heavenly and legal arena; Dickinson came from a family of lawyers with judges as family friends.

The poem’s strategy for entitlement involves a reversal we have seen before: the small with the large, a child with a king, the speaker in her guise as accused/sinner/pilgrim, imagining that one day she will have “the royalty – / To intercede – for Thee –.”

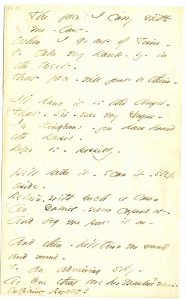

The face I carry with me – last – (F395A, J336)

The face I carry with

The face I carry with

me – last –

When I go out of Time –

To take my Rank – by – in

the West –

That face – will just be thine –

I’ll hand it to the Angel –

That – Sir – was my Degree –

In Kingdoms – you have heard

the Raised –

Refer to – possibly.

He’ll take it – scan it – step

aside –

Return – with such a crown

As Gabriel – never capered at –

And beg me put it on –

And then – he’ll turn me round

and round –

To an admiring sky –

As One that bore her Master’s name –

Sufficient Royalty!

Link to EDA manuscript: “Originally in Amherst Manuscript #fascicle 80. First published in Bolts of Melody (1945), 177. Courtesy of Amherst College, Amherst, MA.”

This poem, in common hymn meter, reprises some of the imagery we have been tracing: the idea of rank and standing, the conferring of degrees (awards and achievements), receiving a crown from a discerning angel, who urges the speaker to—essentially—crown herself. The archangel Gabriel, God’s messenger, who appeared in “For this – accepted breath” heralding the earthly “trance” that compares favorably with heavenly glory, returns here as a foil for the speaker, to suggest the significance of her crown.

William Shurr interprets this “crowning” event as marriage, though the reference at the end to “Master” complicates this interpretation. The crown morphs into “her Master’s name,” an identifying sign that contains “Sufficient Royalty!” Naming, by others and by oneself, is another important form of entitlement Dickinson explores, as we will see in the final poem in this cluster. According to Martha Nell Smith, this manuscript contains erasures that are hard to see in the facsimile.

Sources

Shurr, William. The Marriage of Emily Dickinson: A Study of the Fascicles. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1983.

Smith, Martha Nell. “Dickinson’s Manuscripts.” The Emily Dickinson Handbook. Eds. Gudrun Grabher, Roland Hagenbüchle, Cristanne Miller. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1998, 113-37, 128.

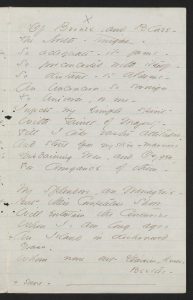

I’m ceded – I’ve stopped being their’s (F353A, J508)

I’m ceded – I’ve stopped

I’m ceded – I’ve stopped

being Their’s –

The name They dropped opon

my face

With water, in the country

church

Is finished using, now,

And They can put it with

my Dolls,

My childhood, and the string

of spools,

I’ve finished threading – too

Baptized, before, without the

Baptized, before, without the

choice,

But this time, consciously,

Of Grace –

Unto supremest +name –

Called to my Full – The Crescent

dropped –

Existence’s +whole +Arc, filled up,

With +one – small Diadem –

My second Rank – too small

the first –

Crowned – +Crowing – on my

Father’s breast –

+A +half unconscious Queen

But this time – Adequate –

Erect,

With + Will to choose,

Or to reject,

And I choose, just a

+Crown –

name] +term

whole are] + Surmise Arc] +Rim • Eye

one] +just one

Crowing] +whimpering • dangling

half unconscious] +too unconscious A half unconscious Queen] +An insufficient Queen

Will] +power Crown] +Throne

Link to EDA manuscript: “Originally in Amherst Manuscript #fascicle 85. First published in Poems (1890), 60-61, with the last stanza in six lines and the alternative for line 20 adopted. Courtesy of Amherst College, Amherst, MA.”

We end the cluster with this ringing acclamation of independence and self-naming. Unlike other poems in this group, notably “Title divine,” with which we began, “I’m ceded–“ is less ambivalent or ambiguous. While the notion of being “ceded” implies being owned and then yielded or surrendered to another power, it also connotes being freed and liberated. The passivity and childishness of being named by others turns into a “conscious” or “half unconscious” (which implies half-conscious) acceptance and embrace of “Grace,” which for Congregationalists was a state requiring receptivity that could only be conferred by God. In the second stanza, the speaker rejects her “second rank,” which she depicts as dependence on “my Father,” as “too small,” for a self-conferring of name, title, rank, and royalty.

The poem seems to repeat itself, or repeat the amazing moment of self-realization as if it cannot get enough of it. The first stanza ends with luscious language of fulfillment and a crown, and not a subjunctive tense in sight: “Called to my full … Existence’s whole Arc, filled up, / With one – small Diadem –.”

The language of the second stanza is even more insistent, and rather than using imagery of filling up associated with the feminine, it uses imagery of adequacy and erection and willfulness associated with masculinity. Thus, the “half-unconscious Queen” becomes “Adequate–/ Erect,” the trochees hammering home the force of this self-nomination. The speaker has become someone with the power to make choices, not be the chosen one, and again, she chooses “just a/ Crown.” But note that each reference to a crown contains a tiny qualification, “small Diadem” and “just a /Crown,” perhaps to guard against hubris?

Sources

Leiter, Sharon. Critical Companion to Emily Dickinson: A Literary Reference to her Life and Work. New York: Facts on File, 2007, 108-11.