On Choosing the Poems

The drama of the passion, as told in the Gospels, includes the story of Jesus’s arrest, trial and suffering, ending with his execution on a hill outside the walls of Jerusalem called Calvary or Golgotha. He is betrayed by Judas, one of his disciples, and denied three times by his primary follower Peter. He is also humiliated and degraded by people mocking him as he carries the cross up the hill and crowning him with thorns. On the cross, he is tortured by the soldiers on guard, and when he cries out to God, he feels abandoned. He suffers a human death out of his love of humankind and willingness to sacrifice himself to redeem humans from the Fall in the garden of Eden.

According to the Calvinist theology that Dickinson’s family believed in, the sacrifice of Jesus fulfills and ends the Covenant of Works that God set up with Adam and Eve in the garden of Eden—that they work and obey his commandment against eating the forbidden fruit. It ushered in what Protestants call The Covenant of Grace, a promise of eternal life for all people who believe in Jesus Christ. Protestants also believe that Christ is at the center of a system of “typology.” Earlier Biblical figures, like Job, anticipated Christ as “types” of him, and later believers could also become part of this divine history by seeing elements of their life in his story.

Dickinson stitches herself and her poetic speakers into Christ’s passion story by taking on crowns and titles such as “Queen” or “Empress of Calvary,” asking God to “Crucify” her, and imagining “Calvaries of love” between lovers separated by unknown forces. See, for example, “I dreaded that first Robin so” (F347, J348), “There Came a day at summer’s full”(F325, J322), “I should have been too glad, I see” (F283, J313). A key poem in this cluster is “Title divine – is mine!” (F194, J1072), explored in an earlier post on “Entitle,” in which Dickinson braids together imagery of crucifixion, love, marriage, and royalty/entitlement. It is an enigmatic poem that circles around the almost ecstatic self-naming exclamation: “Empress of Calvary!” It is as if the speaker heartily embraces her extreme suffering.

As mentioned in the “Overview,” there has been two strands of scholarly approach to Dickinson’s poems of Crucifixion. Earlier readers argued biographically that Dickinson uses the concept and language of the Crucifixion to express her own psychic situation and personal suffering. Dorothy Oberhaus rejects this “secular” reading, putting Dickinson in a larger devotional tradition and arguing that

Dickinson’s internalization of biblical texts is thus not that of an eccentric nineteenth-century American spinster searching for metaphors to express her personal angst but that of the great poets of the Bible and that of the epitome of Christian poets, George Herbert. As type, awesome event demanding sorrowful contemplation, and “Compound Witness” to Christ’s love and transformation of death, the Crucifixion is Dickinson’s most frequent subject and allusion in her poems on the life of Christ.

Oberhaus’s approach is supported by Jane Donahue Eberwein, Shira Wolosky and, to some extent, Patrick Keane. Linda Freedman takes a similarly religious approach to Dickinson’s allusions to the Crucifixion but arrives at a very different conclusion. She argues that Dickinson’s focus on Jesus as the man of suffering

draws attention to the finite infinity because it returns us to the problem of the Word made flesh. Dickinson inherited a concept that articulated both the unbridgeable difference and compact union of humanity and divinity. Christ’s sacrifice emphasizes the condition of that union at the very moment of its dissolution. … Christ suffering is not simply his human resistance to God’s plan, but a locus for both submission and resistance and so for struggle. … The death of the God-man suggests a point of departure for poetry because the inadequacies of religious revelation or poetic representation become the genesis of creative action.

This week, we have gathered together some of the less well-known poems about this theme dated to 1862-1863, clustered around the key poem, “One Crucifixion is recorded – only –.” We also include a list of earlier and later poems that explore the theme of Crucifixion.

The Morning after Wo– (F398, J364)

The Morning after Wo –

'Tis frequently the Way –

Surpasses all that rose before –

For utter Jubilee –

As Nature did not Care –

And piled her Blossoms on –

The further to parade a Joy

Her Victim stared opon –

The Birds declaim their Tunes –

Pronouncing every word

Like Hammers – Did they

know they fell

Like Litanies of Lead –

On here and there – a creature –

They'd modify the Glee

To fit some Crucifixal Clef –

Some key of Calvary –

EDA manuscript: Originally in Poems: Packet XIII, Mixed Fasciles. Includes 27 poems, written in ink, ca. 1862, Houghton Library – (62a). Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. First published in Unpublished Poems (1935), 134, from the fascicle.

Dickinson copied this poem into Fascicle 20 in the 3rd place around autumn 1862. It is written in the short meter of 6686 syllables rhyming abcb. It describes a state Dickinson frequently explored—the aftermath of some crisis, here described as “wo,” a word that appears in 26 of Dickinson’s poems. According to Dickinson’s Webster’s, it means “Grief; sorrow; misery; a heavy calamity,” but also “a curse.” It is frequently used “in exclamations of sorrow. Woe is me; for I am undone. – Isa. vi.”

The morning after the woe referenced in this poem is unsurpassingly beautiful because nature, indifferent to human suffering, “piled her Blossoms on.” Just as birds songs “fell / Like Litanies of Lead,” the alliteration imitates the pounding effect of what usually lifts the spirit. The listener is “a creature,” barely human, who would prefer that the “Glee” of the birds could be modified musically “To fit some Crucifixal Clef / Some key of Calvary”— that is, that nature could reflect its deep sorrow and its unnamed sacrifice.

This is an example of Dickinson's use of the language of the Crucifixion to describe human suffering, not necessarily her own, but suffering she has witnessed or shared. It is notable that, despite Dickinson’s Romantic leanings, nature takes no account of human suffering and cannot express it or console it. In fact, nature further “victimizes” the sufferer, as suggested by the exact rhyme of “Glee” and “Calvary.”

Dickinson wrote a more intense version of this complaint, also focusing on bird song, in “It makes no difference abroad–”(F686, J620) dated to the second half of 1863. In that poem, the speaker complains:

Wild flowers – kindle in the

Woods –

The Brooks slam – all the Day –

No Black bird bates His

Banjo –

For passing Calvary -

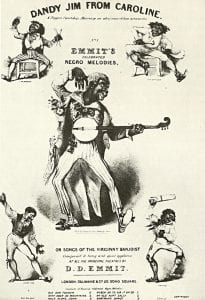

Helen Vendler notes that, at the time, banjos were associated with Black musicians or musicians in blackface, thus turning the “Black bird into an American Black Banjo-Player, the antithesis of the warbling English nightingale.” In Keats’s “Ode to a Nightingale” (1819), a nightingale sings a “high requiem to death” wholly in keeping with the poet’s despairing mood. Vendler also reports that

This was too much for the early editors, who softened it down to “No Black bird bates his jargoning” – from the French jargonner, used of birdsong.

In that poem, in addition to “Calvary,” Dickinson also mentions “Auto da Fe,” the public penance imposed by the Spanish Inquisition on heretics and apostates, and the Day of Judgment as catastrophes to which nature is perfectly indifferent.

Does the allusion to the Crucifixion, or to these other scenarios of suffering, allay the speaker's woe in any way? Does it imply that such sorrow has a larger purpose, or connect us to a larger history? Do the allusions to music, perhaps to psalms and hymns sung in church, offer a means of contemporizing the suffering on the Cross? What is the sacrifice made here?

Sources

Vendler, Helen. Dickinson: Selected Poems and Commentaries. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University, 2010, 286-88.

To put this World down, like a bundle– (F404, J527)

To put this World down,

like a Bundle –

And walk steady, away,

Requires Energy – possibly Agony –

'Tis the Scarlet way

Trodden with straight renunciation

By the Son of God –

Later, his faint Confederates

Justify the Road –

Flavors of that old Crucifixion –

Filaments of Bloom, Pontius Pilate

sowed –

Strong Clusters, from Barabbas'

Tomb –

Sacrament, Saints partook before us –

Patent, every drop,

With the +Brand of the Gentile Drinker

Who +indorsed the Cup –

+stamp + enforced

EDA manuscript: Originally in Poems: Packet XIII, Mixed Fasciles. Includes 27 poems, written in ink, ca. 1862, Houghton Library – (64a). Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. First published in Unpublished Poems (1935), 78, with stanza 3 as a quatrain and the alternatives not adopted.

Like the previous poem, Dickinson copied this poem into Fascicle 20, in the 9th place, sometime in autumn 1862. It is metrically complicated with lots of irregularity especially in the third stanza which takes us right into the landscape of the Crucifixion.

This poem engages explicitly with the elements of the Crucifixion story. It evokes “the Son of God” walking “the Scarlet way,” a road “Trodden with straight renunciation” and “Agony.” Jesus bled and renounced his human life, putting the “World down, like a bundle.” “Pontius Pilate” was the fifth prefect of the Roman province of Judea serving under Emperor Tiberius from AD 26/27 to 36/37, who presided over the trial and execution of Jesus. “Barabbas” was a prisoner, some say insurrectionary against Roman occupation, who was also condemned to die. But when Pilate, on the eve of the Jewish festival of Passover, gave the crowd their choice of one prisoner to spare, they chose Barabbas and called for the crucifixion of Jesus.

Cynthia Wolff argues that this poem explores “the Voice of the Saint,” which Dickinson could only employ with

essential alterations: customarily, the Saint has authority in this world precisely insofar as he or she has relinquished “I” to “God.”

Dickinson cast the efficacy of martyrs in a doubtful light in an earlier poem, “Through the straight pass of suffering” (F187 J792), which she included in a letter to Samuel Bowles in 1862 (L251).

The tone of “To put this World down” hints at the speaker’s attitude to martyrdom. Linda Freedman detects irony here and remarks,

irony functions as a guard against anguish, a way of protecting and distancing oneself from the subjects one cares most about. So it is probably because Dickinson is attracted to the exquisite pain of martyrdom that she cannot help being ironic about its unthinking devotion. … In Dickinson’s simile [of the world as bundle], the martyr must fall for the lie that worldliness is all there is to the world – the doctrine of Christian “renunciation.”

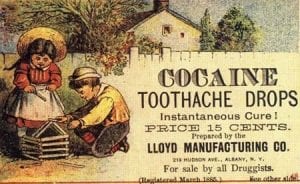

Phrases like “faint Confederates” depict later imitators of Christ as half-hearted, merely sampling the “Flavours of that old Crucifixion.” In addition, the word “Confederates” nods to the army of the Southern States, called the Confederacy, and casts doubt on the nobility of their sacrifice. The last stanza associates the Sacraments, like Baptism and the Lord’s Supper, which link participants to actions and events in Christ’s life, with “Patent” medicines, popular in the 19th century that quickly became associated with fakery and empty promises. Words like “Brand” and “indorsed” extend the commercial implications of “Cup,” a word that alludes both to the “cup of suffering” Jesus begs God to take from him in the garden of Gethsemane before his crucifixion (Luke 22:42) and the cup of wine of the sacrament that holds the symbolic blood Jesus shed to redeem humankind.

Sources

Freedman, Linda. Emily Dickinson and the Religious Imagination. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011, 129-30.

Wolff, Cynthia. Emily Dickinson. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co., Inc. 1988.

189-90.

Must be a Wo (F538, J571)

Must be a Wo –

A loss or so –

To bend the eye

Best Beauty's way –

But – once aslant

It notes Delight

+As difficult a

As +Stalactite –

A Common Bliss

Were had for less –

The price – is

Even as the Grace –

Our Lord – thought no

Extravagance

To pay – a Cross –

+as clarified +Violet

EDA manuscript: Originally in Poems: Packet XXV, Fascicle 28. Includes 23 poems, written in ink, dated ca. 1862, Houghton Library – (138b). Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. First published in Unpublished Poems (1935), 25, with the alternatives for lines 6 and 7 adopted.

Dickinson copied this poem into Fascicle 28 in the 14th position around spring 1863. It is unusual, written in very short lines of dimeter, two feet per line, sometimes rhyming aabb, as in the first stanza, or abab as in the second. The last stanza, which invokes Christ’s Crucifixion, lacks a fourth line, as if mention of this ultimate of sacrifices shuts down language, though the poem seems to argue its necessity for poetic vision. The poem begins with an emphatic trochee: “Must be” to emphasize the imperative mood.

The command is that “woe” or sorrow is necessary for the eye to perceive “Best Beauty,” and once it learns to see “aslant,” it “notes Delight” (a rather tepid verb for that ecstatic noun) in natural things as “difficult,” or “clarified,” as a “Stalactite,” a mineral formation that hangs from the ceilings of caves. The word “Stalactite” takes us into the dripping underground caverns of Dickinson’s gothic imagination, perhaps the crypt from which Jesus emerged resurrected. Its variant, “Violet,” resonates with the next lines about “Common bliss,” since violet is a common color of wild flowers but is also a color Dickinson associates with dramatic sunsets, often metaphors for death and immortality.

The word “aslant” prefigures Dickinson’s poetic philosophy, distilled in this famous poem dated to 1872, “Tell all the truth but tell it slant–Success in Circuit lies” (F1263, J1129). “Must be wo” reveals the origins of slanted vision in a “wo” Dickinson associates with the extreme suffering of the Crucifixion.

Whiles some scholars view the requirement of woe for poetic inspiration as a Calvinist form of weaning oneself from the world, Joan Feit Diehl sees it as part of the Romantic inheritance and reads the poem to suggest that

Crucifixion precedes the bliss of revelation in poetry as well as religion. … In this theory of aesthetic compensation, suffering yields an ability to witness beauty which depends directly upon the force of the pain.

For Linda Freeman, the moment on the cross opens a “vital space of possibility” in which

Dickinson found her angle of vision … Sacrificial narrative forges a poetic way through pain and the peculiar advantage of that way is that it exists on the cusp of the finite and infinite. The stark simplicity of this verse mirrors the stark simplicity of the poet’s choice. “Wo[e]” is not too high a price to pay.

Sources

Diehl, Joan Feit. Dickinson and the Romantic Imagination. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 198, 57-59.

Freedman, Linda. Emily Dickinson and the Religious Imagination. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011, 154-55.

I measure every grief I meet (F550, J561)

I measure every Grief

I meet

With +narrow, probing, eyes –

I wonder if It weighs

like Mine –

Or has an Easier size –

I wonder if They bore it long –

Or did it just begin –

I could not tell the Date

of Mine –

It feels so old a pain –

I wonder if it hurts to live –

And if They have to try –

And whether – could They

choose between –

It would not be – to die –

I note that Some – gone

patient long –

At length, renew their smile –

An imitation of a Light

That has so little Oil –

I wonder if when Years

have piled –

Some Thousands – on the Harm –

That hurt them Early -

such a lapse

Could give them any Balm –

Or would They go on

aching still

Through Centuries of Nerve –

Enlightened to a larger Pain –

In Contrast with the Love –

The Grieved – are many -

I am told –

There is the various Cause –

Death – is but one -

and comes but once –

And only nails the Eyes –

There's Grief of Want – and

Grief of Cold –

A sort they call "Despair" –

There's Banishment from

native Eyes –

In sight of Native Air –

And though I may not

guess the kind –

Correctly – yet to me

A piercing Comfort it

affords

In passing Calvary –

To note the fashions – of the

Cross –

And how they're mostly worn –

Still fascinated to presume

That Some – are like my own –

+Analytic eyes –

EDA manuscript: Originally in Poems: Packet V, Mixed Fascicles. Includes 15 poems, written in ink, dated ca. 1862, Houghton Library – (21a). Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. First published in Poems (1896), 47-48, with the alternative adopted and stanza 4 omitted.

Dickinson copied this poem into Fascicle 27 in the 4th place sometime in summer 1863. It is written in the common meter of 8686 syllables rhyming abcb.

It is an unusually long poem for Dickinson that tells an unusually detailed story about a speaker, gender unspecified, who is filled with an aching grief whose source is undisclosed in this poem and who goes through life “measuring” the grief of other people to see if it is “like Mine.” The speaker wonders about the weight, duration and types of griefs people suffer, including loss via death, which inspires a gruesome image of nailing the eyes shut, want and cold from poverty, suicidal despair, and exile—this last speaks to Dickinson's awareness of the plights of immigrants.

We are left to wonder the purpose of this comparison; does it make the speaker feel less lonely to know that there are “fashions–of the Cross –/And how they’re mostly worn,” a choice of diction that either adapts the superlative suffering of Christ to humanity’s capacity or trivializes these various “Calvaries” as merely a “trend or style,” rather than a “manner; way; mode” (Lexicon).

Although the speaker takes “a piercing Comfort” in realizing “That Some – are like my own,” the tone throughout is strangely remote. “Measure” is a scientific term that suggests quantification and precision. The speaker mentions its “narrow, probing/analytic eyes,” which don’t sound very empathetic, and uses the rather neutral verb “wonder” four times and “note” twice, as well as “fascinated” and “presume,” which all sound distanced and removed. Or perhaps the speaker is shocked or traumatized by grief–or deadened. The adjective “piercing” recalls the soldier piercing Jesus’s side with a spear after he is dead (John 19:34). Perhaps this is another death-in-life narrative.

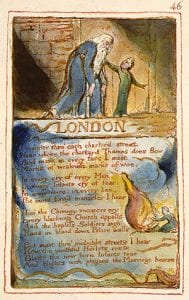

Scholars offer several literary contexts for this poem. Patrick Keane thinks it

resembles Blake’s “London,” in which the Bard of Experience, walking the streets of the fallen city, “mark[s] in every fact I meet / Marks of weakness, marks of woe.”

Helen Vendler offers George Herbert’s poem “The Sacrifice” (1633), in which Jesus, uttering the reproaches to his people formalized in the Good Friday liturgy as the Improperia, repeats two versions of the refrain: “Was ever grief like mine?” and “Never was grief like mine.”

Vendler’s context confirms Dorothy Oberhaus’s contention that Dickinson’s poems on the life of Christ fall into the great devotional tradition of which Herbert is also a part. What seems unique here is the quotidian nature of this superlative grief, what Vendler calls

Dickinson’s democratic multiplication of the Crucifixion of Jesus.

Sources

Keane, Patrick J. Emily Dickinson’s Approving God: Divine Design and the Problem of Suffering. Columbia: University of Missouri Press 2008, 95-96.

Vendler, Helen. Dickinson: Selected Poems and Commentaries. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University, 2010, 250-54.

One Crucifixion is recorded – only – (F670, J553)

One Crucifixion is recorded -

only –

How many be

Is not affirmed of Mathematics –

Or History –

One Calvary – exhibited to stranger –

As many be

As Persons – or Peninsulas –

Gethsemane –

Is but a Province – in the

+Being's Centre –

Judea –

For Journey – or Crusade's

Achieving –

Too near –

Our Lord – indeed – +made

Compound Witness –

And yet –

There's newer – nearer

Crucifixion

Than That –

+Human Centre +bore

EDA manuscript: Originally in Poems: Packet XVII, Mixed Fasciles. Includes 25 poems, written in ink, ca. 1862, Houghton Library – (96b). Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. First published in Bolts of Melody (1945), 260, from a transcript of A (a tr523), with the alternative for line 13 adopted.

Dickinson copied this poem into Fascicle 30 in the 19th place, third from last, around the second half of 1863. It has a unique structure, alternating lines as long as 11 syllables with very short lines, dimeters and, in the last three stanzas, monometer lines of one foot. Dorothy Oberhaus suggests this structure imitates the form of the cross in the long lines crossed by short ones. In fact, George Herbert, another poet Oberhaus includes in the devotional tradition whom Dickinson knew and loved, wrote several “shape” poems, one in the shape of an altar called “The Altar” and one in the shape of “Easter Wings.”

This poem has occasioned lots of commentary and contention. Scholars agree that Dickinson declares the event of the Crucifixion of Jesus not singular or mythical or even strictly physical, but rather the public face of many daily existential crucifixions suffered by ordinary humans that go unrecorded by history. In some way, the poem distills into a belief the realizations of “I measure every grief I meet” (F550, J561) where the speaker perceives and “measures” the various “Calvaries” of other people. Except that there is much more passion and compassion in this poem.

The heart of the poem opens with the word “Gethsemane,” an urban garden at the foot of the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem, where Jesus spent a night of agony before his Crucifixion. The speaker then suggests that this iconic moment in the Passion story “is but a Province–in the / Being’s Centre–.” The variant “Human Centre” makes the point even clearer: this is a place of agony in the human soul.

The other important image is that Jesus “made Compound Witness,” a phrase that allows for many readings. Cynthia Wolff says that “the materialistic thrust” of this image

seems to stand without ironic commentary: Christ’s sacrifice was “Compound” because His death was offered in behalf of man; but it is also like compound interest upon a loan, piling up credit upon credit as years pass and increasing numbers of people find it relevant to their own experience.

Scholars agree that Dickinson “internalizes the meaning of the Crucifixion,” but in what sense and to what effect? Dorothy Oberhaus offers a religious reading of the poem in the light of a Christian devotional tradition and several other poems in Dickinson’s “American Gospel” about the life of Christ. By contrast, many agree with Robert Weisbuch, who argues that Dickinson “bends the Biblical vocabulary to an account of her own psychic condition” and thus diminishes the religious meaning of the Crucifixion. Likewise, Wolff finds that Dickinson’s

Christ becomes noteworthy not because He was divine, but because He was human; the meaning of Calvary is defined not by transcendental values, but by earthly ones. The Crucifixion becomes a prototype for human misery … no more than a trope for extraordinary pain … strategies for describing the terms of our existential condition.

But Wolff regards this as “a radical reversal” of authority.

Sources

Oberhaus, Dorothy. “‘Tender Pioneer’: Emily Dickinson's Poems on the Life of Christ.” American Literature 59.3 October 1987: 341-58, 354.

Weisbruch, Robert. Emily Dickinson’s Poetry. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1975, 80-81.

Wolff, Cynthia. Emily Dickinson. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co., Inc. 1988, 457.

Sources

Freedman, Linda. Emily Dickinson and the Religious Imagination. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011, 126, 141, 153.

Keane, Patrick J. Emily Dickinson’s Approving God: Divine Design and the Problem of Suffering. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2008.

Oberhaus, Dorothy. “‘Tender Pioneer’: Emily Dickinson’s Poems on the Life of Christ.” American Literature 59. 3 October I987: 341-58, 354.

Wolosky, Shira. “Public and Private in Dickinson’s War Poetry.” A Historical Guide to Emily Dickinson. Ed. Vivian Pollak. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004. 103-131.

Additional poems about Crucifixion from throughout Dickinson’s life

Jesus! thy Crucifix (F197, J225)

I shall know why when (F215, J193)

The Test of Love – is Death – (F541, J573)

He gave away his Life – (F530, J567)

Forget! The Lady with the Amulet (F625, J438)

That I did always love (F652, J549)

To know just how he suffered (F688, J622)

Where thou art – that is Home (F749 J725)

Spurn the temerity (F1485, J1432)

One crown that no one seeks (F1759, J1735)

Proud of my broken heart (F1760, J1736)