On Choosing the Poems

As mentioned in the Overview, scholar Michelle Kohler identifies a group of six autumnal-themed poems Dickinson wrote in the year of 1862 that form a suite linked by their

haunting, sometimes violent imagery and their self-conscious ironic tones.

They are:

“My first well Day – since many ill – ” (F 288)

“’Twas just this time, last year, I died” (F 344)

“I know a place where Summer strives” (F 363)

“There are two Ripenings – ” (F 420)

“The name – of it – is ‘Autumn’ – ” (F 465)

“A Solemn thing within the Soul” (F467)

Kohler goes on to read “Dickinson’s decidedly intemperate poems” as ironic and revisionary echoes of Keats’s famous “Ode to Autumn” (1819), a decidedly temperate poem that celebrates the mild joys of a specifically English autumn season. She also frames Dickinson’s poems as responding to the accounts of war in the national periodicals she read.

In approaching this suite of poems, Kohler builds on the work of two scholars: Karen Jackson Ford, who argues that Dickinson’s “poetics crystallize in response” to “oppositional rhetorical pressures” produced by reading and communicating with writers she doesn’t agree with; and Elizabeth Petrino’s adaptation of John Hollander’s theory of literary echo as “subtly but aggressively revisionary, particularly by means of displacement and fragmentation.” Kohler, as we will see, traces these two strategies in Dickinson’s autumn poems, showing ultimately that

her poems navigate not only Keats’s rhetoric but also the literal and rhetorical terrain of the Civil War,

and that they are

porous, embattled texts that highlight their own artificiality among other rhetorical possibilities and that create space to echo and satirize both the ostensible containment of the English ode and the messiness of the American periodical.

David Cody focuses specifically on the capstone poem in Kohler’s suite, “The name – of it – is ‘Autumn’ -” (F 465), but in doing so, offers some helpful frameworks for reading all the poems selected for this week. He notes that violent imagery of autumn was a staple of the writers in the so-called Azarian School, New England women prose writers who favored lush, intense and dramatic descriptions and whose influence on Dickinson we traced in an earlier post.

Cody also reiterates the point made by other scholars that Dickinson, like her New England poetic precursors Anne Bradstreet and Edward Taylor, subscribed to the view of Sir Thomas Browne (1605-1682), author of the book of reflections, Religio Medici. Browne described the world as a “universal and publick manuscript, that lies expansed unto the eyes of all … full of mystical letters …,” making the seasons available as sacramental emblems. Imagery of blood as the means of saving grace was a familiar trope, as in Taylor’s Meditation 2:26:

Oh! richest Grace! Are thy Rich Veans then tapt

To ope this Holy Fountain (boundless Sea)

For Sinners here to lavor off (all sapt

With Sin) their Sins and Sinfulness away?

In this bright Chrystall Crimson Fountain flows

What washeth whiter, than the Swan or Rose.

(June 1698)

Cody observes that “Sanguinary imagery of this sort, still very much in vogue in the religious literature of Dickinson’s day, played a particularly important role in popular revivalist hymns” such as Frederick William Faber’s “Blood is the price of heaven,” in which the word “blood” occurs seven times and “bleeds” occurs sixteen times. He also finds similar imagery in the hymns of Isaac Watts, very familiar to Dickinson, who described the saints

Dress’d in the garments of his Son,

And sprinkled with his blood (IV 193)

Watts apostrophized:

Bless’d Fountain! springing from the veins

Of Jesus our incarnate God. (IV 191)

Cody concludes that in her poetry on this theme, Dickinson

is offering her own treatment of this traditional theme.

In selecting the poems for this week, we took our cue from Kohler’s list, but left off the first poem, which we treated in our post on Illness and added a few more from 1862 that amplify the autumnal and war imagery.

’Twas just this time, last year, I died (F344, J445)

'Twas just this time, last

year, I died.

I know I heard the Corn,

When I was carried by the Farms –

It had the Tassels on –

I thought how yellow it would

look –

When Richard went to mill –

And then, I wanted to get

out,

But something held my will.

I thought just how Red -

Apples wedged

The Stubble's joints between –

And Carts went stooping

round the fields

To take the Pumpkins in –

I wondered which would

miss me, least,

And when Thanksgiving, came,

If Father'd multiply the plates –

To make an even Sum –

And would it blur the

Christmas glee

My stocking hang too high

For any Santa Claus to reach

The altitude of me –

But this sort, grieved myself,

And so, I thought the other

way,

How just this time, some

perfect year –

Themself, should come to me

EDA manuscript: Originally in Poems: Packet XIII, Mixed Fasciles. Includes 27 poems, written in ink, ca. 1862, Houghton Library – (61a). Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. First published in Poems (1896), 198-99.

Dickinson copied this poem into Fascicle 16 in the 9th position sometime in Summer 1862. It is spoken by a young person who died the year before in the autumn and wonders about the lives of those left behind.

Mary Loeffelholz considers it one of “A great string of Dickinson poems of the early 1860s with posthumous speakers,” along with “I felt a Funeral in my Brain” (F340, J280), “I heard a Fly buzz – when I died –” (F591, J465) and “Because I could not stop for Death –” (F479, J712). All of them may have been inspired by “The Amber Gods,” a dramatic story with a posthumous narrator written by Harriet Prescott Spofford, who was part of the “Azarian School” of women writers. One question posed by these posthumous narratives, according to Loeffelholz, is

how to locate the leading edge of the contemporary: what if becoming modern means realizing we have already died? Died without seeing either God or the posthumous family reunion promised by popular nineteenth-century Christian theology?

For Michelle Kohler, this poem illustrates the strategy Dickinson uses throughout this suite of poems, taking “multiple rhetorical or conceptual approaches” to autumn. She argues that the speaker, perhaps a young girl, “recounts the autumnal imagery and events that surrounded her funeral” by echoing “the apples and ‘stubble-plains’” in Keats’s “Ode to Autumn.” But in the final stanza the speaker decides to think an “other way,” which Kohler reads as a resistant echo of Keats’s admonition to “Think not of [the songs of Spring]” but of the different music of autumn. Kohler finds this strategy of thinking otherwise about autumn, which Jed Deppman associates with Dickinson’s “try to think” poems, in all of the poems in the group.

What if the speaker here is not a young girl, but a soldier and casualty of the war? His alternative way of thinking, his consolation, is to imagine his family members joining him in death “just this time, some perfect year” as if after this autumn of battle, the season of autumn cannot be disentangled from death.

Or what if, as Annelise Brinck-Johnsen posits, the speaker is a “they,” neither male nor female but outside the gender binary, and their thinking an “other way” and wish for the living to “come to me,” then,

occurs within a queer temporal space that engages with and critiques heteronormative narratives?

Sources

Brinck-Johnsen, Annelise. “Lyric Ecstasies of Queer Time.” Women's Studies 47:3, 2018, 333-349, 345.

Kohler, Michelle. “The Ode Unfamiliar: Dickinson, Keats, and the (Battle)fields

of Autumn.” Emily Dickinson Journal 22, 1, 2013: 30-54, 35.

Loeffelholz, Mary. “U.S. Literary Contemporaries.” Emily Dickinson in Context. Ed. Eliza Richards. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013, 129-38, 136.

I know a place where Summer strives (F363, J337)

I know a place where

Summer strives

With such a practised Frost –

She – each year – leads her

Daisies back –

Recording briefly – "Lost" –

But when the South Wind

stirs the Pools

And struggles in the lanes –

Her Heart misgives Her, for

Her Vow –

And she pours soft Refrains

Into the lap of Adamant –

And spices – and the Dew –

That stiffens quietly to Quartz –

Opon her Amber Shoe –

EDA manuscript: Originally in Poems: Packet VI, Fascicle 18. Includes 13 poems, written in ink, dated ca. 1862, Houghton Library – (23b). Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. First published in Poems (1891), 148.

Dickinson copied this poem into Fascicle 18 in the 2nd place sometime in autumn 1862. It is written in the common meter of the hymn form with fairly exact rhymes: Frost-lost, lanes-Refrains, Dew-Shoe. We considered this poem in an earlier post on Fascicle 18, where we explored the theme of Resurrection as a site of contention. The poem stages a struggle between Summer and the Frosts of Autumn, words that need capitalization because they stand for what biographer Alfred Habegger calls “emblems of the phases of psychic existence” for a poet increasingly confined to the physical boundaries of her father’s home.

Dickinson wrote many poems about summer, a season that Sharon Leiter notes,

occupies a place of special prominence in [Dickinson’s] poetry, not merely because of the number of times it is named or evoked, but because of its preeminence in her value system.

For example, in the poem, “I Reckon – When I count at all –” (F533, J569), the speaker lists “First – Poets – then the Sun – / Then Summer – Then the Heaven of God–.” Summer, as this list implies, is more precious to the speaker than heaven because it is a heaven on earth. Psychically, then, for Dickinson, summer represents a period of “intensity and fecundity,” but also, sadly, ephemerality.

The “vow” referred to in this poem that Summer took regretfully, is probably an allusion to the vow of Demeter, the Greek goddess of the harvest. When her daughter Persephone was abducted by Hades, the god of the underworld, Demeter’s overwhelming grief halted the progress of the seasons, and all living things began to die. Demeter vowed to reverse this damage if Persephone would return to her, which she does. But because Persephone had eaten some pomegranate seeds in the underworld, she must return there every year for several months during which, again, the world dies. Demeter’s vow brings on the rebirth of spring and the eventual harvests of autumn.

Michelle Kohler finds in this poem “The most explicit restaging of Keats’s ode,” specifically turning its “stubble-plains [touched] with rosy hue” into bloody fields of battle.

Here, late summer leads her soldiers (“Daisies”) into battle with autumnal frost, and the daisies become casualties … again and again …

Although there is “regret and grief in the ‘soft Refrains’” of stanza two, Kohler notes a shift that complicates this “as Dickinson’s third stanza rethinks the seasonal cyclicality of death—a cyclicality that is true for daisies but not for soldiers—as permanent stiffening.” She concludes about the whole suite of poems:

Altogether, the poems’ concern with death, battle, vexed landscapes, and fallen “Being[s]” provides compelling reason to see Dickinson wrestling with, on one hand, a Keatsian autumn too subdued and, on the other, a New England autumn far too agitated.

Sources

Habegger, Alfred. My Wars are Laid away in Books. New York: Random House, 2001, 161.

Kohler, Michelle. “The Ode Unfamiliar: Dickinson, Keats, and the (Battle)fields

of Autumn.” Emily Dickinson Journal 22, 1, 2013: 30-54, 44-45.

Leiter, Sharon. Critical Companion to Emily Dickinson: A Literary Reference to her Life and Work. New York: Facts on File, 2007, 139-140.

It dont sound so terrible – quite – as it did – (F384, J426)

It dont sound so terrible -

quite – as it did –

I run it over – "Dead", Brain -

"Dead".

Put it in Latin – left of my school –

Seems it dont shriek so – under rule.

Turn it, a little – full in the face

A Trouble looks bitterest –

Shift it – just –

Say "When Tomorrow comes this

way –

I shall have waded down one Day".

I suppose it will interrupt me

some

Till I get accustomed – but

then the Tomb

Like other new Things – shows

largest – then –

And smaller, by Habit –

It's shrewder then

Put the Thought in

advance – a Year –

How like "a fit" – then -

Murder – wear!

EDA manuscript: Originally in Poems: Packet XXVII, Fascicle 19. Includes 13 poems, written in ink, ca. 1862, Houghton Library – (144c). Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. First published in Bolts of Melody (1945), 306, among the poems incomplete or unfinished, as three stanzas of 4, 4, and 6 lines, from a transcript of A (a tr509).

Dickinson copied this poem into Fascicle 19 in the 6th place sometime in autumn 1862. R. W. Franklin’s note on the poem offers some context:

The poem appears to have been prompted by the death of Lieutenant Frazar A. Stearns, the son of the president of Amherst College. Frazar, aged twenty-one, was killed in action at Newbern, N.C., on 14 March 1862. His funeral was held in Amherst on 22 March. ed wrote of these events in a letter to her Norcross cousins, and in a letter to Samuel Bowles she used words that parallel the poem. [see Letter 256]

We cited this poem in an earlier post on the death of Frazar Stearns, and though Kohler doesn’t include it in her suite of poems, it illustrates Dickinson’s struggles to come to terms not only with the individual death of a family friend and very young man, but with the many deaths brought to public consciousness during the bloody fall of 1862. Because of the family connection, Dickinson most likely would have seen the elegiac volume, Adjutant Stearns, compiled by his father William Stearns, which appeared in October 1862 and which turned the fallen soldier into martyr for the War.

About this poem, Faith Barrett says:

the representation of death is wholly divorced from any wartime context in the speaker’s intense focus on her own state of shock and grief. She stammers out a response to an unthinkable, self-shattering loss, repeating the news of the death again and again in a vain attempt to absorb it. She repeats to herself the platitudes that are used to comfort the mourning. The threat that lies just beneath the surface of the poem, however is that the speaker will never be able to accept this death. Here Dickinson resists wartime ideologies that called on families to understand the death of a soldier as a sacrifice necessary to national reunion. By calling the death — whose cause and context the poem refuses to explain — a “Murder,” the poem refuses to ascribe to it a compensatory meaning.

Sources

Barrett, Faith. “Slavery and the Civil War.” Emily Dickinson in Context. Ed. Eliza Richards. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013, 198-215, 209.

There are two Ripenings – (F420C, J332)

There are two Ripenings –

One – of Sight – whose Forces

spheric +round

Until the Velvet Product

Drop, spicy, to the Ground –

A Homelier – maturing –

A Process in the Bur –

Which Teeth of Frosts,

alone disclose –

In +still October Air –

+wind +far –

EDA manuscript: Originally in Poems: Packet X, Mixed Fascicles. Includes 14 poems, written in ink, ca. 1858-1862, Houghton Library – (47c). Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. First published in Letters (1894), 147, from the copy to Turner (Anthon) ([B.2] lost); reprinted in Life and Letters (1924), 207, and from there in Further Poems (1929), 200, as two five-line stanzas: the literal arrangement of lines in the fascicle (C).

Dickinson copied this poem into Fascicle 14 in the 16th position. It is written in the short meter of 6686 syllables with a longer line 3. R. W. Franklin notes that Dickinson made three copies, one now lost, in 1862:

The copy in Fascicle 14 (h47) was recorded about autumn 1862 with alternatives for three lines. ed appears to have copied the core of the poem as it stood in her draft and the alternatives for lines 2 and 8, and then gone back over the whole, adding additional alternatives from the draft for lines 7 and 8.

Helen Vendler notes that Dickinson’s two-stanza poems often contrast two things and frames the “Ripenings” contrasted here with Edgar's famous line to his father Gloucester, in Shakespeare’s King Lear: “Ripeness is all” (Act 5, scene 2), as well as giving a nod to Keats. Vendler finds that Dickinson compares the “exquisite and profuse natural ripening” of fruit, with the more prized “interior ripening of the spirit.” She raises the possibility that Dickinson may be obliquely referring to gender and the biological ripening of birth. But Vendler prefers a spiritual reading in which

the Soul – maturing only under the Teeth of chilled expectations, and aware of the approach of a wintry death after its October chastening– is “disclosed” only as the body is wounded by the “Teeth” of suffering, and will be fully revealed only in the apocalyptic uncovering of the Last Day.

Focusing solely on the echoes of Keats, Kohler finds that Dickinson transforms his singular, comforting “ripeness” in “the core” of Autumn to “two Ripenings” that are “more conflicted” and refuse “to posit either internal or external coherence” especially in terms of an account of the external world. Rather, “autumn is constituted by the multiple, shifting rhetorical and conceptual stances that structure our thought.” What is significant about Dickinson’s difference from Keats for Kohler is

that she repeatedly uses this structure to re-introduce the pathological view of autumn that Keats largely excises from his ode. … an ideological effort, conscious or not, to construct … the landscape seen through ideological notions of Englishness as enshrined in political and aesthetic traditions.

Although we cannot know what precisely Dickinson discerned in Keats’s “Ode,” Kohler argues

that Dickinson’s echoes of Keats’s autumn form ways of thinking about autumn that are, by contrast, explicitly aligned with disease, death, excess and tropical imagery.

Sources

Kohler, Michelle. “The Ode Unfamiliar: Dickinson, Keats, and the (Battle)fields

of Autumn.” Emily Dickinson Journal 22, 1, 2013: 30-54, 38-41.

Vendler, Helen. Dickinson: Selected Poems and Commentaries. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University, 2010, 191-93.

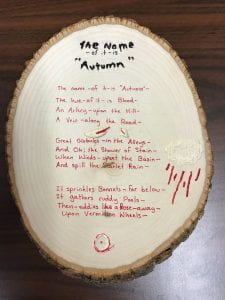

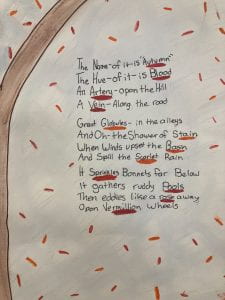

The name – of it – is “Autumn” – (F465, J656)

The name – of it – is "Autumn" –

The hue – of it – is Blood –

An Artery – opon the Hill –

A Vein – along the Road –

Great Globules – in the Alleys –

And Oh, the Shower of Stain –

When Winds – upset the Basin –

And spill the Scarlet Rain –

It sprinkles Bonnets – far below –

It +gathers ruddy Pools –

Then – eddies like a Rose – away –

+ Opon Vermillion Wheels -

+stands in – • makes Vermillion –

+ And leaves me with the Hills.

EDA manuscript: Originally in Poems: Packet XIX, Fascicle 22. Includes 23 poems, written in ink, dated ca. 1862, Houghton Library (105d). Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. First published in Youth's Companion, 65 (8 September 1892), 448, with the alternative for line 12 adopted; also Bingham, Ancestors’ Brocades (1945), 159n. Bolts of Melody (1945), 38, with the alternatives not adopted, from a transcript of A (a tr214).

Dickinson copied this poem into Fascicle 22 in the 10th place, about late 1862, a few poems before the next two poems in our group, which amplify the bloody imagery of this arresting poem. It is written in a loose common meter and its rhymes tell the story: Blood – Road, Stain – Rain, Pools – Wheels; variants: Vermillion – Hills.

David Cody carefully lays out “the rich, complex and increasingly remote cultural moment in which [this poem] came into being.” In doing so, he considers it “to embody Dickinson’s response to one of the most bloody and traumatic periods in our national history.” He shows how Dickinson drew on

a remarkably wide range of literary sources, including contemporary travel essays and magazine stories, the Bible, religious poetry, anatomical texts, war news, and works by favorite authors such as Sir Thomas Browne, Ralph Waldo Emerson, John Ruskin, and Thomas Wentworth Higginson.

He also cites work by Tyler B. Hoffman, who insists that

the landscape Dickinson depicts is a strikingly accurate transcription of the terrain around Sharpsburg, the town through which Antietam Creek flows.

But Cody argues from sources and especially a story by Catharine Maria Sedgwick titled “The White Hills in October” appearing in Harper’s Monthly in December 1856, that Dickinson’s blood-spilling “Basin” is based on a much-touted romantic nook near the “Notch” in the White Mountains of New Hampshire. The poem’s implications of blood-letting and sacrifice echo the national rhetoric of the Civil War as

a great purgative sacrifice or blood-offering demanded of an erring nation by an angry God.

Cody shows Dickinson in close conversation with contemporary sources, condensing and distilling them to produce a “boldly experimental word-painting” that “transcend[ed] traditional poetic vocabularies.”

Library of Congress

For Michelle Kohler, this poem is the culmination of her dual approach to the suite of autumnal poems of 1862, showing Dickinson’s aggressive revisions of Keats’s quelling imagery in his “Ode to Autumn” (1819) and her insistence on representing an overly “agitated” and violent New England autumn. Much of the poem’s imagery has been linked to reportage about Civil War battlefields, in particular, the “Sunken Road” near Sharpsburg, which was the site of fierce battles and later renamed “Bloody Lane.” Its horror was captured in one of the photographs Matthew Brady exhibited in New York City. Kohler’s insight is to see the poem as “also a rhetorical battlefield” that rethinks autumn in pathologized terms.

In this light, she focuses on the last image, in which the blood that has drenched the textual landscape is cleared away:

Then – eddies like a Rose – away –

Opon Vermillion Wheels.

This image is nothing if not constructed, and self-consciously so. As Kohler says: “roses do not eddy, roses do not have wheels, and things that eddy do not do so on wheels.” Furthermore, “vermillion,” which also occurs in Dickinson’s variants for lines in the poem, is a flamboyantly “poetic” word. This all leads Kohler to conclude that the poem is

not only a civilian’s admission of the remoteness of her experience of war; it is more pressingly an ironic, parodic, and very serious wartime meditation on figural conventions.

And in a final twist, Kohler views the “bathos in the poem” as a means to parody the tendency of contemporary newspapers and journals, which placed grisly, detailed war reporting next to light and humorous editorials and drawings of the latest women's fashions. This she finds echoed in the "Bonnets" sprinkled with scarlet rain. Kohler concludes:

The poems themselves are thus fields of conflict between profoundly different ways of thinking autumn and death.

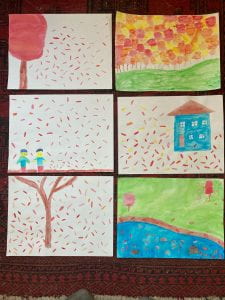

Video illustration by a Crossroads Academy student, 2023: RenaNameAutumn23

Sources

Cody, David. “Blood in the Basin: The Civil War in Emily Dickinson’s ‘The

name of it is Autumn.’ ” Emily Dickinson Journal 12. 1 (2003): 25-52, 25-26, 29, 33.

Hoffman, Tyler B. “Emily Dickinson and the Limit of War.” Emily Dickinson Journal 3.2

(1994): 1-18.

Kohler, Michelle. “The Ode Unfamiliar: Dickinson, Keats, and the (Battle)fields

of Autumn.” Emily Dickinson Journal 22. 1 (2013): 30-54, 47-50.

A Solemn thing within the Soul (F467, J483)

A Solemn thing within the

Soul

To feel itself get ripe –

And golden hang – while

farther up –

The Maker's Ladders stop –

And in the Orchard far below –

You hear a Being – drop –

A wonderful – to feel the sun

Still toiling at the cheek

You thought was finished –

Cool of eye, and critical of

Work –

He shifts the stem – a little –

To give your Core – a look –

But solemnest – to know

Your chance in Harvest moves

A little nearer – Every sun

The single – to some lives.

EDA manuscript: Originally in Poems: Packet XIX, Fascicle 22. Includes 23 poems, written in ink, dated ca. 1862, Houghton Library – (106b). Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. First published in Bolts of Melody (1945), 244, from a transcript of A (a tr118), with the first three words of line 10 as the last of line 9.

Dickinson copied this poem into Fascicle 22 in the 12th place around late 1862. It has a somewhat unusual form: two stanzas of six lines with 868686 syllables rhyming abcbdb and one stanza of four lines of 6686 syllables rhyming abcb.

It seems like a continuation of “There are two Ripenings -,” discussed above, with the ripening here explicitly “within the Soul.” Cynthia Wolff sees the first two and a half lines as depicting in “conventional emblematic language” how “the ‘golden’ gift of faith ripens until the worthy Christian is ready to be gathered unto the Father.” She detects a shift with the image of “The Maker’s Ladders” that stops farther up, not reaching the ripe fruit, and we “hear a Being – drop –” without being gathered up.

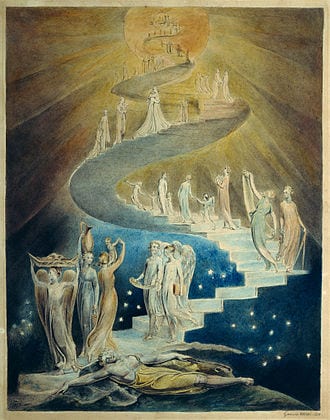

This ladder is an allusion to Jacob, son of Isaac and Rebekah, grandson of Abraham and Sarah, who dreamed about a ladder or staircase reaching to heaven with Angels ascending and descending, and the voice of God coming from the top blessing him. Wolff argues that because the ladder in Dickinson's poem stops, it suspends the speaker, who hears another “Being” ripen, fall and perish into the abyss. This “glimpse into Heaven, then, is not glorious but terrifying.” By the end of the poem, the speaker realizes

that this process of gathering in the souls is not a promise at all, but merely, “a chance in Harvest” … If it holds out the hope of eternal life, it offers the more imminent danger of an unspeakable drop into nothingness.

Kohler argues that the poem “attenuates … the disease-producing contact between the sun and ripening fruit” in the second stanza, building on the pathology of autumn she spies in “There are two Ripenings” discussed above. Here, the sun, which at first feels “wonderful” on one’s cheek, becomes an emblem for a Maker who is “Cool of eye, and critical of Work” and shifts you around like an apple to scrutinize the state of your Core/soul. The approach of Harvest and the sun is daunting. Kohler concludes:

In fact, where things bend, sit, sleep, gather, and otherwise hover aloft in a kind of temperate stasis throughout Keats’s poem, things actively fall to the ground throughout Dickinson’s six poems. … Indeed, precisely because Dickinson’s poems foreground the constructedness that Keats’s poem suppresses, they make it clear that Keats’s poem is as much a rhetorical battleground as are Dickinson’s.

Sources

Kohler, Michelle. “The Ode Unfamiliar: Dickinson, Keats, and the (Battle)fields

of Autumn.” Emily Dickinson Journal 2. 1 (2013): 30-54, 41-43.

Wolff, Cynthia. Emily Dickinson. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co., Inc. 1988, 305-07.

Whole Gulfs – of Red, and Fleets – of Red – (F468, J658)

Whole Gulfs – of Red, and

Fleets – of Red –

And Crews – of solid Blood –

Did place about the West -

Tonight –

As 'twere specific Ground –

And They – appointed Crea –

tures –

In Authorized Arrays –

Due – promptly – as a

Drama –

That bows – and disappears –

EDA manuscript: Originally in Poems: Packet XIX, Fascicle 22. Includes 23 poems, written in ink, dated ca. 1862, Houghton Library – (106c,d). Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. First published in Bolts of Melody (1945), 23-24, from a transcript of A (a tr253), with the alternative adopted.

Dickinson copied this poem into Fascicle 22 in the 13th position, sometime in late 1862, placing it just after the previous poem we discussed, “A Solemn thing within the Soul.” Though it doesn’t explicitly refer to autumn or the seasons, its insistent emphasis on red and sunset makes it part of this suite of poems.

On the literal level, Dickinson is describing a vivid, even lurid, sunset, but we might recall Thoreau’s observation in “Autumnal Tints” that “October is [the year’s] sunset sky.” Furthermore, words like “Gulfs,” “Fleets,” “Crews” and, of course, “solid Blood” suggest that the speaker is seeing in her mind’s eye and evoking the bloody battles of the autumn of 1862. Shira Wolosky calls this

a traumatized view of the sunset. War here serves as the model in terms of which Dickinson perceives the day’s decline and which renders that decline terrible and fearful.

The speaker amplifies the suggestion of war by comparing the crimson sky to “specific Ground,” and we wonder which “ground” in particular the speaker has in mind. Much of battle strategy turns on taking specific ground.

But who is the actor here? The Dickinson Lexicon cites this poem as illustrating its second definition of “crew:” “Group; [fig.] cloud; sunset formation.” This makes “Crew” a noun parallel with “Gulfs” and “Fleets” and “solid Blood,” a parallelism reinforced by the maritime theme. But there is another way to read the first stanza, with “Crews” as the agent (displaced grammatically in the sentence) “placing” the gulfs and fleets of solid blood in the West, as if they were divine but demonic figures and the West was the specific ground of a battlefield.

Then, “Crews” becomes the referent of “They” in stanza two, agents who “appointed Creatures / In Authorized Arrays,” as would leaders of a crew of workmen, sailors, or, perhaps, soldiers—and “rebels.” One of Dickinson's Webster’s definitions of “crew” is

A company, in a low or bad sense, which is now most usual; a herd; as, a rebel crew. Milton. So we say, a miserable crew.

The common qualifiers of the word “crew” in Paradise Lost are “hapless,” “banisht,” and, best of all, “horrid,” all referring to Satan’s army of fallen angels. The word “creatures” emphasizes their inhuman or dehumanized status.

In this reading, the crews placing gulfs and fleets of solid blood in the western sky are soldiers in a rebel army, who are like “creatures” in a “drama,” acting their part, then bowing and disappearing, as the lurid streaks of the sunset fade. However we read this poem, it reinforces Michelle Kohler’s contention that for Dickinson in 1862, autumn as the sunset of the year was beset with disturbance, violence, and death.

Sources

Hallen, Cynthia, ed. Emily Dickinson Lexicon. Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University, 2007.

Wolosky, Shira. “Emily Dickinson’s War Poetry: The Problem of Theodicy.” Massachusetts Review 25.1 (Spring 1984): 22-41, 26-27.

Sources

Cody, David. “Blood in the Basin: The Civil War in Emily Dickinson’s ‘The name of it is “Autumn.”’” Emily Dickinson Journal 12. 1 (2003): 25-52, 34-38.

Kohler, Michelle. “The Ode Unfamiliar: Dickinson, Keats, and the (Battle)fields of Autumn.” Emily Dickinson Journal 22. 1 (2013): 30-54, 30-32, 50-51.