On Choosing the Poems

So many of Dickinson’s poem are about nature and all its aspects, but we are particularly interested this week in gardens, those plots of ground, cultivated and wild, often demarcated as special, and full of flowers, vegetables, herbs, shrubs and fruit trees. As mentioned in the Overview for this week, Dickinson was an avid gardener in a culture of gardening. But she also wrote about “the garden in the Brain” in “Within my garden rides a bird” (F370A, 500), one of the poems in this week’s cluster, and wrote to her friend Susan of “that garden unseen” (L92), the garden as metaphor for life, love, beauty and the locus of meditations on many subjects.

Of course, it is impossible to talk about gardens without invoking the great Ur-garden, Eden, and the events that transpired there. Dickinson’s gardens are also sites for her re-visioning of the stories of creation and fall as well as resurrection and immortality. Writing to her beloved brother Austin, away at law school, on October 25, 1851, she said:

Home is a holy thing – nothing of doubt or distance can enter it’s blessed portals. I feel it more and more as the great world goes on and one and another forsake, in whom you place your trust – here seems indeed to be a bit of Eden which not the sin of any can utterly destroy – (L59).

This is a sentiment Dickinson will repeat throughout her life: home is “a bit of Eden” and Paradise is a garden, which is just outside the door.

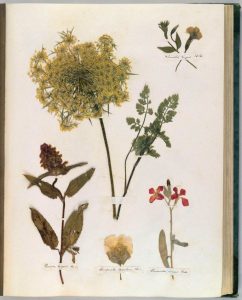

In discussing Dickinson’s garden politics with Melissa Zeiger’s Spring 2018 English class on “Garden Politics: Literature, Theory, Practice” at Dartmouth College, we asked them to read a chapter from the classic work on the subject, Judith Farr’s The Gardens of Emily Dickinson (2004), which strives

to place Emily Dickinson’s love for gardens in the cultural context of her day; describe its origin, development, and relation to her family interests; and to consider the architecture and contents of her planted garden as a kind of analogue to those hundreds of poems and poetic letters about crocuses, daisies, daffodils, gentians, trillium, mayflowers, hyacinths, lilies, roses, jasmine, and other flowers that comprise the landscape of her art.

Indeed, the Victorian era had a distinctive “language of flowers,” of which Dickinson and other poets made ample use.

We also asked the students to read Mary Kuhn’s more recent essay from Spring 2018, titled “Dickinson and the Politics of Plant Sensibility,” which makes a very different and startling argument, grounded in a post-human understanding of ecology and global politics. Kuhn explodes the notion of gardening in Dickinson’s time as solely a “domestic enterprise,” finding that seed catalogues and nurseries sold plants from around the world. Dickinson herself was the recipient of seeds from a childhood friend who became the wife of an Amherst College-trained missionary who traveled to and worked in Syria. In fact, Kuhn views “horticulture as a transcultural, geopolitical enterprise” and finds evidence in Dickinson’s poems that she realized and recorded “how the global traffic in plants transformed local environments” and gave her access to gardens on a global scale.

In addition to exploring the mobility of plants, Dickinson also explored the theory of their capacity to feel. Kuhn argues that

By Dickinson’s lifetime, plant sentience was an established, if hotly debated, current of thought within natural history.

Kuhn finds ample evidence in the poetry that rather than flowers as analogies for humans, Dickinson found a different kind of agency, subjectivity and social organization in gardens, one that did not reflect human experience and from which we could learn. In fact, Kuhn argues, Dickinson displaces human consciousness from its position at the top of the great chain of being and

challenges the notion that feeling is essentially a human characteristic.

Kuhn’s approach is to read Dickinson’s representations of nature as empirical and material, rather than metaphorical. Thus, her sentimental use of flowers, bees and butterflies evokes a real world of mobile, autonomous, sentient creatures of which we, as humans, are merely a part.

In effect, Judith Farr and others taught us to read Dickinson’s gardens as domestic, locally situated, and as metaphors and symbols of the soul and spirituality. Newer readers like Kuhn are asking us to “resist the metaphorical” and read these gardens as literal, material and on a global scale that collapses the near and the far. You will see how the students took these radical ideas and ran with them.

Sources

Farr, Judith, with Louise Carter. The Gardens of Emily Dickinson. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2004, ix.

Kuhn, Mary. “Dickinson and the Politics of Plant Sensibility.” ELH, 85:1 (Spring 2018), 141-170; 152,154, 160.

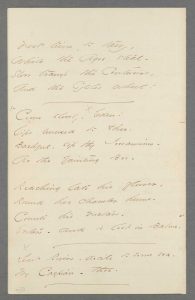

Come slowly – Eden! (F205A, J211)

Come slowly — Eden!

Lips unused to Thee —

Bashful — sip thy Jessamines —

As the fainting Bee

Reaching late his flower,

Round her chamber hums —

Counts his nectars —

Enters — and is lost in Balms.

EDA manuscript: "Originally in Poems: Packet XXXVII, fascicle 10. Includes 22 poems, written in ink, ca. 1860-1861. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. First published in the Independent, 43 (12 March 1891), 1, from the copy to Susan Dickinson (A); correspondence relating to this appearance, which Lavinia Dickinson protested, is in Bingham, Ancestors’ Brocades (1945), 114-20. Poems (1891), 85-86, from the fascicle (B)."

Here are the students' responses to this extraordinary poem.

Caroline Cline

Around the time that she wrote “Come Slowly—Eden!” in 1861, Emily Dickinson authored letters that evince emotional distress resulting from an unarticulated ordeal—one which greatly influenced the tone of her writing (“Emily Dickinson: The Writing Years [1855-1865]”). Many other poems she wrote in 1860 and 1861 convey relatively dark content, and several also employ the term “Eden” to represent the afterlife or heaven. Dickinson’s poems “Did the Harebell loose her girdle” (1860), “As if some little Arctic flower” (1860), and “I’m the little ‘Heart’s Ease’!” (1860) discuss “Eden” in the context of the natural world. Like “Come slowly—Eden!” they all use floral imagery, and the first and third mention bees. Thus, the intersection between nature and Eden was one of continued thematic concern for Dickinson in the early 1860s. In “Come Slowly—Eden!” Dickinson employs formal attributes present in many of her poems—specifically dashes, slant rhyme, irregular meter, and extended simile—to serve the piece’s unorthodox stance; in so doing, Dickinson subverts religious conceptions of Eden and supplants imperialism with natural generation.

Around the time that she wrote “Come Slowly—Eden!” in 1861, Emily Dickinson authored letters that evince emotional distress resulting from an unarticulated ordeal—one which greatly influenced the tone of her writing (“Emily Dickinson: The Writing Years [1855-1865]”). Many other poems she wrote in 1860 and 1861 convey relatively dark content, and several also employ the term “Eden” to represent the afterlife or heaven. Dickinson’s poems “Did the Harebell loose her girdle” (1860), “As if some little Arctic flower” (1860), and “I’m the little ‘Heart’s Ease’!” (1860) discuss “Eden” in the context of the natural world. Like “Come slowly—Eden!” they all use floral imagery, and the first and third mention bees. Thus, the intersection between nature and Eden was one of continued thematic concern for Dickinson in the early 1860s. In “Come Slowly—Eden!” Dickinson employs formal attributes present in many of her poems—specifically dashes, slant rhyme, irregular meter, and extended simile—to serve the piece’s unorthodox stance; in so doing, Dickinson subverts religious conceptions of Eden and supplants imperialism with natural generation.

“Come slowly—Eden!” is characterized by non-traditional formal poetics that underscore the dissentious nature of its content. The poem urges heaven to reveal itself gradually to the unfamiliar speaker. Indeed, in accordance with this message, Dickinson uses dashes that serve to ease the reader into a more gradual, elongated reading of the poem. This work has two quatrains with the rhyme scheme ABCB DEFE. Lines 6 and 8 are a slant rhyme, and lines 1 and 3 can be read as a less obvious slant rhyme—making the poem more measured and stilted. In conjunction with the dashes, the oblique rhyme scheme renders the tone of the poem uneasy and solemn, consistent with its discussion of death. The poem’s meter deviates from both common meter and short meter. The syllables in each line are 5575 and 6547—a pattern that does not correlate perfectly to any recognizable form. The unpredictable meter echoes the unconventional, fractured, and complicated content of the poem’s stanzas. This interplay between form and content is apparent in the first stanza, when the speaker challenges classical conceptions of Eden. She uses “Jessamines” (l. 3) as an example of heaven’s fruit. Though it could conceivably have existed in a Middle Eastern Eden, jessamine, or jasmine, is not a doctrinal “Garden of Eden” plant. These simultaneous formal and figurative transgressions amplify one another and further challenge established paradigms.

The speaker’s normative divergence is not merely religious, as she uses a simile in the poem that reveals some of Dickinson’s political impulses. The poem likens a human’s entrance into heaven to a bee’s death in a flower. The bee is a particularly potent symbol because of its generative function as a natural pollinator. According to Mary Kuhn, “In presenting the motion of natural phenomena, Dickinson provides an alternative narrative to the kinds of botanical circulation fostered in imperial contexts” (Kuhn 150). The act of pollination destabilizes an understanding of botanical diversity rooted in completely human-facilitated, imperialist circulation. Instead, the speaker posits the necessary, organic motion of flowers by depicting the bee’s expiry in the process of pollination. The bee’s metaphorical ascension to heaven—represented as the prelapsarian state—implies that before the fall, and in the afterlife, natural creation reigns over sinful imperialism. In this reading, Dickinson disrupts the assumption of imperialist dominion over the natural world.

Works Cited

“Emily Dickinson: The Writing Years (1855-1865).” Emily Dickinson Museum,

Kuhn, Mary. "Dickinson and the Politics of Plant Sensibility." ELH, vol. 85 no. 1, 2018, pp. 141-171 doi:10.1353/elh.2018.0005

Isabel Hurley

Isabel Hurley

The stanzas of “Come slowly–Eden!” conform to a regular rhythm–each line begins with a trochee and most contain three stressed syllables–but for two notable exceptions. Their exceptional status in the poem’s rhythm indicates their importance to the poem’s meaning, so I analyze each to provide various contexts for the poem. As White Heat notes, Dickinson’s critics, namely Thomas Wentworth Higginson, “found Dickinson’s meter unruly and untutored”–most of all, unorthodox. Every deviation from formal, orthodox meter and content was a risk, liable to be understood as a deficit of Dickinson’s poetic ability as opposed to an innovation. Thus, I analyze the “oddities” of her meter, as they reflect Dickinson’s intentions under heightened attention, to provide various contexts for the poem.

The first lies in the poem’s opening, which defies the rule of trochees with the spondee “Come slowly,” whose two stressed syllables slow the phrase, emphasizing its content as well as the sudden arrival at “–Eden!” (l. 1). “Come slowly–Eden!” appears to be set in an earthly garden, its protagonists the Bee and his flower, yet the heavenly garden, Eden, announces its presence even before the terrestrial garden appears. Thus, we can interpret “Eden” in a variety of ways, from paradise to familiar garden to purity to climax.

Dickinson’s poem “Did the Harebell loose her girdle” presents the stereotype of Eden as an ideal of purity, while simultaneously criticizing this view:

Did the Harebell loose her girdle

To the lover Bee

Would the Bee the Harebell hallow

Much as formerly?

Did the "Paradise" – persuaded -

Yield her moat of pearl -

Would the Eden be an Eden,

Or the Earl -= an Earl? (F134A, J213, ll. 1-8).

While in “Come slowly–Eden!” the Bee’s “nectars”—whose definitions in the Emily Dickinson Lexicon include “heavenly messenger,” “life after death,” and “mutual bliss”—indicate that Eden is paradise, whether spiritual or sexual, in the above poem, Dickinson places “Paradise” in quotes, suggesting that the heavenly garden should not represent the flower–nor, by extension, the woman. If this “lover Bee” succeeds and the Harebell “–persuaded–” yields, “Would the Eden be an Eden,” the poem asks, implying that any expression of a woman’s sexuality entails her fall from grace, under the assumption that chaste Eden is a desirable standard for all women. The Harebell’s predicament suggests a more pessimistic conclusion for the flower of “Come slowly,” raising the question of what happens to the Eden which is no longer an Eden. The Bee has agency, counting, entering, getting lost––in contrast, the flower has all but disappeared by the end of the poem, her devaluing manifested in her invisibility.

Eden’s ideological power is driven by its central role in Creation—a power Dickinson undermines with irreligious comments and rhetorical questions, such as “Do they wear ‘new shoes’ — in ‘Eden’ —,” whose insincere tone is less than awestruck by Eden’s biblical role (“What is– ‘Paradise’–” [F241A, J215, l.7]). The title itself—“What is– ‘Paradise’–” reveals a lack of faith and points to an interpretation of Eden apart from the religious sense. Thus, another possibility is “Eden” as the opposite of “purity,” its common connotation. Though “come slowly,” taken out of context, would not be overtly suggestive, the erotic images throughout the poem– “lips,” “enters,” “balms”— allow the speaker’s order, or wish, to “Come slowly” to reveal a desire to prolong her present enjoyment. The title given to the poem by Dickinson’s first editors, “Apotheosis,” and the poem as they printed it, replete with sexuality, insinuate that abstinence may be further from heavenliness than sexual ‘impurity’ (“Apotheosis”). However, it may not be “apotheosis” the flower wishes to delay, so much as the Bee’s return. Paula Bennett reads Dickinson’s “Crisis” to “suggest that for some women ‘anticipatory’ sex–that is, the sexual pleasure achieved through clitoral masturbation–is preferable to the so-called fulfilled sex of marital intercourse” (Bennett 241). “Come slowly” resounds with anticipation, placing the flower in the pleasurable state before “fulfilled” sex. The Harebell’s example as well shows that to “yield her moat of pearl,” representative of female sexuality and pleasure according to Bennett, is to lose her worth, even herself. While her “pearl” remains hers alone, she is whole and hallowed (6).

The second exception to the poem’s rhythmic regularity occurs with “Enters,” due to its placement in the stanza. Both the meter and rhyme pull “Enters” towards the previous line, as that adjustment would create two balanced lines with three stressed syllables each, without disturbing the slant rhyme of “flowers” with “nectars”–in its place, “enters.” Even “her” and “chamber” echo this rhyme scheme from within the line (6). Thus, the displacement of “enters” is unsettling, but resolves with “–and is lost in Balms,” which completes a slant rhyme with “hums” (6). While “lost” here is a resolution, in “Just lost, when I was saved!” it instead seems to imply denial from heaven.

Just lost, when I was saved!

Just heard the world go by!

Just girt me for the onset with eternity

When breath blew back – (F132A, J160, ll. 1-4)

This poem even appears on the same manuscript page as “Come slowly.” The speaker in “Just lost” wishes, “Next time to tarry,” echoing the sentiment to prolong the moment before arriving at “Eden,” or analogously, just before “the onset with eternity” (ll. 16, 3). Perhaps for the second speaker, “eternity” is the afterlife, making the moment before eternity—life. We are left to decide whether prolonging the approach to Eden or arriving there is more desirable—is Eden death, climax, or the end of independence-granting female pleasure? The uncertainty alone would be ample reason to tarry.

Sources

Bennett, Paula. “Critical Clitoridectomy.” Signs, Vol. 18, No. 2 (Winter, 1993), pp. 235-259, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3174975.

Schweitzer, Ivy. “February 5-11: Poems on Meter.” White Heat, Dartmouth Journeys, 5 Feb. 2018, journeys.dartmouth.edu/whiteheat/on-choosing-poems-feb-5-11/.

Liza Wemakor, “Aquatics, Arousals, and Arrivals”

In Emily Dickinson’s poetry, aquatics and erotics play together. I’ll examine that pattern in these three pieces, identified by their first lines: “Just lost, when I was saved!” (F132B), “Come slowly – Eden!” (F205A), and “Least Rivers – docile to some sea” (F206A)

In Emily Dickinson’s poetry, aquatics and erotics play together. I’ll examine that pattern in these three pieces, identified by their first lines: “Just lost, when I was saved!” (F132B), “Come slowly – Eden!” (F205A), and “Least Rivers – docile to some sea” (F206A)

I view these works as a trilogy of arousal:

The first stage, “Just lost, when I was saved!,” sketches discovery and anticipation. It describes the delight of losing salvation. Of slipping out of normalcy. Of letting some old matters die. Of trading intimacy with a known world for intimacy with a possible world. “Just felt the world go by! … / And on the other side / I heard recede the disappointed tide!”

The fantasy beyond disappointment is stimulation. While figures of fixation are vague at this stage – “Some Sailor, skirting foreign shores / Some pale reporter, from the / awful doors / Before the Seal!” (my emphasis) — their sensual potential is attractive enough that the speaker requests: “Just girt me for the onset / with Eternity.” The first definition for girt in Emily Dickinson’s Lexicon is: “Surround; encircle; wrap; wind a sash around.” This falls in line with the poem’s theme of anticipation. Girting is a way of preparation.

The faintly-sexual figures who dally with virginal “shores” and sealed “awful doors,” comparable to women’s condemned erogenous entrances, inspire the speaker to think of forever-fantasies, eternities, and “Next times.”

If we presume the speaker’s femininity, she imagines a future set in a private sphere, perhaps the only sphere where she can be touched and unbothered – “By ear unheard – / Unscrutinized by eye -.” Stimulation and freedom, which could very well be the same thing, are delayed in this liminal stage. Lovers only anticipate “and tarry, / While the Ages steal – / Slow tramp the Centuries / And the Cycles wheel.” The definition for tarry in the Lexicon is: “Linger; loiter; lag behind; wait before doing something.” The definition for tramp in the same lexicon is: “Vagrant; wanderer; homeless person.” Like “anticipation,” both terms are associated with suspension, unfulfillment, and/or shifting without reaching.

“Come slowly – Eden!,” arousal’s second stage, shows someone beginning to give up on waiting and give into touch. The lovers fumble – “Lips unused to Thee – / Bashful – “ but they divine each other and each of their attributes, pronouncing “Lips”, “Thee”, and “Bashful” like God. Though the faint lover reaches “late his flower,” he still “Enters – and is lost in Balms.” Among the definitions of balm in the Lexicon are: “Pollen; [fig.] fragrance; bouquet; floral aroma; scent of flower pollen” and “Nectar; nourishing liquid; revitalizing fluid.” The speaker could speak of a sea of flowers (“Jessamines”), a sea of nectar, or perhaps seas of nectars within seas of flowers. In this piece, the speaker has the sea she imagined by her Sailor’s side, and it is she. She knows her wet body as Balms, healing and liquidizing by way of touch.

The utopian Eden may have come slowly, but it did come. In “Least rivers docile to some sea,” arousal’s third stage, the lovers enjoy the after-languor. The speaker seems to describe her lover as “My Caspian – thee,” but she could also describe herself. The Caspian Sea is an inland body of water into which many rivers flow. If sex is giving and getting, the speaker may not only share her wetness, but replenish it with her lover’s. This third stage of arousal could be the easy docility that comes after waiting, reaching, and finally, resting. It is sensible that this last poem is the shortest, given the ephemerality of arrival. What comes soon goes again.

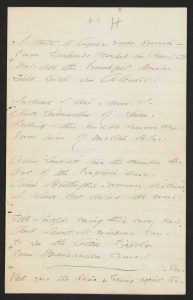

I taste a liquor never brewed (F207B, J214)

I taste a liquor never brewed -

From Tankards scooped in Pearl -

Not all the Frankfort Berries

Yield such an Alcohol!

Inebriate of air – am I -

And Debauchee of Dew -

Reeling – thro' endless summer days -

From inns of molten Blue -

When "Landlords" turn the drunken Bee

Out of the Foxglove's door -

When Butterflies – renounce their "drams" -

I shall but drink the more!

Till Seraphs swing their snowy Hats -

And Saints – to windows run -

To see the little Tippler

+From Manzanilla come!

+Leaning against the Sun!

EDA manuscript: "Originally in Poems: Packet XIV, Mixed Fasciles. Includes 33 poems, written in ink, ca. 1860-1862. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. First published in Springfield Daily Republican (4 May 1861), 8, from the lost copy ([A]); also Springfield Weekly Republican (11 May 1861), 6. Poems (1890), 34, from the fascicle (B), with both alternatives adopted."

Here is a student's response to this joyous poem.

Anna Reed

Dickinson’s poem, “I taste a liquor never brewed” (F 207B, J214), creates a relationship between the nature in her garden and an intoxicating liquor in a way that seems in some ways absurd, yet completely within the realm of imagination. She ascribes to the plants and insects a human spirit while simultaneously maintaining their “wild” aspects. Though, there is more to the purpose behind the poem than portraying a garden in an absurdist light.

Dickinson’s poem, “I taste a liquor never brewed” (F 207B, J214), creates a relationship between the nature in her garden and an intoxicating liquor in a way that seems in some ways absurd, yet completely within the realm of imagination. She ascribes to the plants and insects a human spirit while simultaneously maintaining their “wild” aspects. Though, there is more to the purpose behind the poem than portraying a garden in an absurdist light.

The first aspect of the poem that caught my eye was the first line, “I taste a liquor never brewed.” Within this line Dickinson makes the reader aware that this intoxication she feels is unique to her, that it cannot be reproduced. She reaffirms this in the first stanza with the lines, “Not all the Frankfort Berries / Yield such an Alcohol!” Through this first stanza I get the sense that she is enjoying the life within her conservatory. In the second stanza, she exposes her position with “Inebriate of air- am I – / And Debauchee of Dew – / Reeling – thro’ endless summer days – / From inns of molten Blue – /.” Specifically the line where she calls herself a Debauchee of Dew is an interesting line; and using the lexicon for reference, the word debauchee is defined as someone who is debauched, or who indulges in extraneous pleasure. Being debauched in reference to dew seems slightly absurd. This theme continues with the way she animates the bees and butterflies. She injects these seemingly insignificant insects with a spirit that extends the metaphor between nature and alcohol.

Though the connection between plant life and intoxication is not a novel concept, her approach and portrayal of this “nature drunk” is unique. She uses her wit and comfort with the garden to contort it in such a way that she portrays her personal sentiments effectively, while still making it seem simultaneously familiar and foreign.

To examine the poem a bit further, I would argue that this is a love poem. Though not obvious at first glance, there are clear parallels between the alcohol and love, or perhaps the man she’s in love with. Returning to the first line of the poem, Dickinson tells us that this “liquor” was never brewed; but moreover, that it is something unique to her. The remainder of the poem is filled with imagery of alcohol in words like Frankfort, which is a city in Germany known for its brews. She continually hints at a substance from which she is taking extraneous pleasure. In particular, the third stanza mentions a “landlord” and a “bee”, which could be easily be related back to herself and this lover. The final stanza is the most difficult to read through this lens, though if Tippler could be associated with herself, it begins to make more sense. I interpret it to mean that, she, the Tippler (meaning one who is a drunkard) is disobeying the Church with this relationship.

Seraphs and Saints both carry religious connotations, giving the impression that their hurry to observe the Tippler means that these holy people would disapprove of her actions. The parenthesis saying (Leaning against the- Sun) could very well be a nod to Icarus. Following this parenthetical interjection is the final line: “- From Manzanilla come! /.” Manzanilla was a port in Cuba whose primary export was rum, which would be a final nod to her addiction to this alcohol, this love. It is interesting, though, that she chose to represent her love and desire for this unknown lover through a garden. It might be that gardens, especially Eden, have a connotation of being paradise and sin. Perhaps, then, she sees herself as Eve giving in to blissful desire within the garden.

To briefly summarize, “I taste a liquor never brewed” is a poem that strategically uses absurdist imagery to obscure the undertones of love and desire. Dickinson represents a garden with a humanistic spirit to overwhelm the poem with allusions to drunkenness. I argue that this drunkenness is in fact a heady lust for an unknown lover disguised as a liquor.

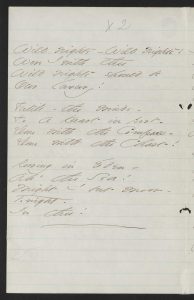

Wild nights – Wild nights! (F269A, J249)

Wild nights – Wild nights!

Were I with thee

Wild nights should be

Our luxury!

Futile – the winds -

To a Heart in port -

Done with the Compass -

Done with the Chart!

Rowing in Eden -

Ah – the Sea!

Might I but moor -

tonight -

In thee!

EDA manuscript: "Originally in Poems: Packet VIII, Fascicle 11. Includes 20 poems, written in ink, ca. 1861. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. First published in Poems (1891), 97, with the last word of line 11 as the first of line 12."

Here is a student's response to this amazing poem.

Turiya Hamlet Adkins

“Wild Nights – Wild Nights” by Emily Dickinson is number sixteen out of eighteen in a collection of poems in her eleventh fascicle. “Why – do they shut Me out of Heaven?” (J248, Fr268) proceeds “Wild Nights – Wild Nights” in which Dickinson questions or rather begs to be let into heaven. Dickinson prefaces “Wild Nights – Wild Nights” interestingly because in the first stanza it remains unclear if here Dickinson addresses the night itself or someone she had wild nights with, which has an implication of romance and sex. This implication poses the question, Why – do they shut Me out of Heaven. The poem following “Wild Nights – Wild Nights” in the fascicle is “I shall keep singing!” Here she associates herself with the birds and her poetry and rhymes with their song. Both “Wild Nights – Wild Nights” and “I shall keep singing!” evoke a sense of longing. In “Wild Nights – Wild Nights” a longing for more wild nights (whether with someone else or not) and in “I shall keep singing!” a longing for freedom and liberation

“Wild Nights – Wild Nights” by Emily Dickinson is number sixteen out of eighteen in a collection of poems in her eleventh fascicle. “Why – do they shut Me out of Heaven?” (J248, Fr268) proceeds “Wild Nights – Wild Nights” in which Dickinson questions or rather begs to be let into heaven. Dickinson prefaces “Wild Nights – Wild Nights” interestingly because in the first stanza it remains unclear if here Dickinson addresses the night itself or someone she had wild nights with, which has an implication of romance and sex. This implication poses the question, Why – do they shut Me out of Heaven. The poem following “Wild Nights – Wild Nights” in the fascicle is “I shall keep singing!” Here she associates herself with the birds and her poetry and rhymes with their song. Both “Wild Nights – Wild Nights” and “I shall keep singing!” evoke a sense of longing. In “Wild Nights – Wild Nights” a longing for more wild nights (whether with someone else or not) and in “I shall keep singing!” a longing for freedom and liberation

The first line of the third stanza, “Rowing in Eden,” is yet another example of many possible meanings. Here Eden could refer to a harbor, or it could be a reference to the Garden of Eden. Anytime the Garden of Eden is indicated so is the story of the garden and its inhabitants, Adam and Eve. If in the first stanza Dickinson is in fact writing of a romance then this acts as a brilliant parallel between her and her lover and the inevitable doom of Adam and Eve. This possibility arises the eternal question of whether it was Adam or Eve’s fault for the fall of Eden.

I tend my flowers for thee – (F367A, J339)

I tend my flowers for thee -

Bright Absentee!

My Fuschzia's Coral Seams

Rip – while the Sower – dreams -

Geraniums – tint – and spot -

Low Daisies – dot -

My Cactus – splits her Beard

To show her throat -

Carnations – tip their spice -

And Bees – pick up -

A Hyacinth – I hid -

Puts out a Ruffled Head -

And odors fall

From flasks – so small -

You marvel how they held -

Globe Roses – break their satin

flake -

Opon my Garden floor -

Yet – though – not there -

I had as lief they bore

No crimson – more -

Thy flower – be gay -

Her Lord – away!

It ill becometh me -

I'll dwell in Calyx – Gray -

How modestly – alway -

Thy Daisy -

Draped for thee!

EDA manuscript: "Originally in Poems: Packet VI, Fascicle 18. Includes 13 poems, written in ink, dated ca. 1862. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. First published in London Mercury, 19 (February 1929), 353-54, and Further Poems (1929), 141."

Here are the students' responses to this intriguing poem.

Abby Bresler

“I tend my flowers for thee” describes a blooming and vivacious garden. The poem mentions many flowers—fuschzia, geraniums, daisies, carnations, hyacinth, globe roses—and a cactus. A cactus, not suited for the Massachusetts climate, stands out in this group of plants. Similarly, Emily Dickinson, unusually worldly for her small town of Amherst, Massachusetts, might feel like an outsider in her own habitat. Some of the flowers have possessive adjectives attached and some do not. Why does Dickinson write, “my flowers,” “My Fuschzia,” “My Cactus,” “Thy flower,” and “Thy Daisy,” but simply, “Geraniums,” “Low Daisies,” “Carnations,” “A Hyacinth,” and, “Globe Roses”?

“I tend my flowers for thee” describes a blooming and vivacious garden. The poem mentions many flowers—fuschzia, geraniums, daisies, carnations, hyacinth, globe roses—and a cactus. A cactus, not suited for the Massachusetts climate, stands out in this group of plants. Similarly, Emily Dickinson, unusually worldly for her small town of Amherst, Massachusetts, might feel like an outsider in her own habitat. Some of the flowers have possessive adjectives attached and some do not. Why does Dickinson write, “my flowers,” “My Fuschzia,” “My Cactus,” “Thy flower,” and “Thy Daisy,” but simply, “Geraniums,” “Low Daisies,” “Carnations,” “A Hyacinth,” and, “Globe Roses”?

The first stanza of “I tend my flowers for thee” has an aabb rhyme scheme, and the second stanza begins with cc. However, the next lines, “My Cactus – splits her Beard / To show her throat” mark the beginning of a more complex and sporadic rhyme scheme throughout the rest of the poem. Not only do the lines represent a disruption of rhyme, they represent a disruption of dichotomies and biological boundaries with the phrase “splits her beard,” since females do not naturally grow beards.

This poem is a part of Fascicle 18, which consists of poems that explore the topics of resurrection, the afterlife, gardens as paradise, gardens with a missing lover, and gardens as a woman’s body (Schweitzer). “I tend my flowers for thee” shares Fascicle 18 with the famous, “After a great pain, a formal feeling comes.” This pain, perhaps referring to the “great terror” in Dickinson’s life (Schweitzer), suggests that while she is writing these poems, she is working through her pain.

“I tend my flowers for thee” echoes pain through words of violent action: “rip,” “splits,” “fall,” and “break.” While these words could be interpreted as violent and painful, they could also be interpreted as active, representing plants’ agency and mobility (Kuhn). The first line of the poem reads, “I tend my flowers for thee,” yet Dickinson doesn’t describe herself tending the garden. Rather, she describes the plants performing actions: “My Fuschzia’s Coral Seams / Rip,” “Carnations – tip their spice” “Globe Roses – break their satin / flake.” By describing the plants’ autonomous actions, Dickinson suggests that plants live a life independent of their gardeners. Since Dickinson often used plants to represent larger environmental political ideas (Kuhn), she could be suggesting that the natural world exists for far more than just human consumption and enjoyment.

Central to this poem is the absence of someone. Who is the “thee”? Who is the “Bright Absentee”? Who is “Her Lord”? Why does Dickinson use the familiar thee/thy to directly address someone, except for in the line, “You marvel how they held”? Dickinson further describes absence and mystery through the phrases “I hid,” “not there,” and by describing the flowers’ activity, “while the Sower – dreams.”

The dreaming Sower could be a seed sower. Could it also be a sewer? The poem contains sewing and fabric imagery: “My Fuschzia’s Coral Seams / Rip,” “Globe Roses – break their satin / flake,” and, “Thy Daisy – / Draped for thee!” While Dickinson sowed seeds, she also sewed fascicles, making little booklets by threading her poems together. Perhaps Dickinson sees a connection between cultivating seeds into flowers and flowers into gardens, and cultivating words into poems and poems into fascicles. In fact, during Dickinson’s time, anthology meant both a collection of poems and a collection of flowers (Oxford English Dictionary).

“I tend my flowers for thee” could be about female sexuality and a female enjoying her own body in the other person’s absence. “Thy Daisy – / Draped for thee!” implies that someone’s flower is their own. Since flowers are often metaphors for female sexuality (Bennett), Dickinson could be suggesting that the woman can be a sexual being for herself. Dickinson furthers this idea with her lines, “My Cactus – splits her Beard / To show her throat.” Since a beard can be a metaphor for pubic hair (Zeiger), the lines suggest that the speaker is opening herself up. By describing the flowers and cactus as having agency, Dickinson could be implying that a woman’s body should have agency.

Works Cited:

Bennett, Paula. “Critical Clitoridectomy: Female Sexual Imagery and Feminist Psychoanalytic Theory.” Signs, vol. 18, no. 2, 1993.

Kuhn, Mary. “Dickinson and the Politics of Plant Sensibility.” ELH, vol. 85, no. 1, 2018

“Anthology, n.” Oxford English Dictionary, http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/8369?redirectedFrom=anthology#eid.

Schweitzer, Ivy. “Emily Dickinson and Garden Politics.” ENGL 64.02. Dartmouth College, New Hampshire. 18 April 2018. Guest Lecture.

Zeiger, Melissa. “Garden Politics.” ENGL 64.02. Dartmouth College, New Hampshire. 30 April 2018. Meeting.

Willow Pagán

In Fascicle 18, Dickinson describes “soul defining experiences” that usually lead to moments of escape or release (Poetry Foundation). “I tend my flowers for thee” is the sixth poem of Fascicle 18, a compilation of seventeen poems written by Emily Dickinson in autumn of 1862. The flowers and plants in “I tend my flowers for thee” undergo active release, by ripping, splitting, tipping, falling, and breaking. The plants’ action is enhanced by Dickinson’s descriptions of their colors, scents, and textures, creating a garden that is not only a space or a metaphor, but also a community of autonomous and perhaps sentient life.

In Fascicle 18, Dickinson describes “soul defining experiences” that usually lead to moments of escape or release (Poetry Foundation). “I tend my flowers for thee” is the sixth poem of Fascicle 18, a compilation of seventeen poems written by Emily Dickinson in autumn of 1862. The flowers and plants in “I tend my flowers for thee” undergo active release, by ripping, splitting, tipping, falling, and breaking. The plants’ action is enhanced by Dickinson’s descriptions of their colors, scents, and textures, creating a garden that is not only a space or a metaphor, but also a community of autonomous and perhaps sentient life.

In addition to being an avid writer, Emily Dickinson was a voracious reader and botanist, and as “I tend my flowers for thee” reveals, she was interested in the debate on plant sentience. In her essay on “Dickinson and the Politics of Plant Sensibility,” Mary Kuhn discusses different theories on “the lively materiality of plants … which could challenge human efforts to understand or control them.” Dickinson’s use of action verbs throughout the poem creates a vitality of tone, subverting the perception of the gardens as soft, passive, and gentle, while lending a more active and forceful timbre. In the first stanza, Dickinson writes: “My Fuchsia’s Coral Seams Rip – while the Sower – dreams.” While the garden is understood by Christians as a space in which humans exert an ordering control over nature, the guardian of this garden sleeps while the plants ripen, blossom, and burst autonomously.

In Dickinson’s style of “choosing not choosing,” the Sower could refer to the narrator as sewer of ripped seams, menstruating female, or absent masculine lover. The poem begins with a perfect rhyme: “I tend my flowers for thee – Bright Absentee!” establishing the narrator not as a gardener but merely a tender, while “blurring the line between a lover and a deity or higher power.” The ambiguity of both the narrator as passive sower and the “Bright Absentee” as lover and deity reveal layers of meaning and questions about plant sentience and agency, human relation to plants and animals, as well as sexuality and religion. As Dickinson disables the dominance of the gardener, she also uses archaic language such as “lief,” “becometh,” and “always,” perhaps to suggest a revision of ancient and inculcated Western beliefs on human dominance over nature. “I tend my flowers for thee” makes readers wonder about the liveliness of plants and the possibility of a deity because as a botanist and skeptic entrenched in a Puritan society, these were questions Dickinson herself considered

The poem oscillates between a spiritual and sexual tone through words with double meanings and interchangeable syntax, allowing agency to shift. For example, the lines of the third and fourth stanzas can be read in alternating pairs to change the meaning: “And Bee’s – pick up – A Hyacinth – I hid – Puts out a Ruffled Head.” The interchangeable syntax allows the poem to read multiple ways with either the bees or the Hyacinth as the active subject, while the past action of the sower was overrode by the plant.

Dickinson’s resistance to iambic pentameter as well as other formal rules of poetry allows her to write freely, using perfect and slant rhymes, dashes, and staccato rhythms to build up a verbal texture that is as varied and active as the flowers in her garden. Dickinson’s use of tactile texture and visible color, from hairy, ruffled, and satin, to fuchsia’s, corals, crimsons, and grays, complement the verbal structure of the poem. Each plant seems like a sentient being undergoing metamorphosis, both beautiful, fragrant, and painful. Dickinson contextualizes the seasonal friction of winter melting into spring as resistant, but inexorable. Such changes, as the blossoms break out of their hidden state, are accompanied by a discomfort similar to the female experience of puberty and menstruation. Although Dickinson’s perception of plants exists independently of feminine symbolism, the associations are nonetheless present and powerful, imbuing the poem with added meaning and relatability. According to both Dickinson’s poetry and Thoreau, “the mystery of the life of plants is kindred with that of our own lives” (Kuhn, 156).

Sources

Cameron, Sharon. Choosing Not Choosing: Dickinson's Fascicles. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992.

Killen, Madeline. “Resurrection?” White Heat, March 26 – April 1, 1862: Fascicle 18.

Kuhn, Mary. "Dickinson and the Politics of Plant Sensibility." ELH, vol. 85 no. 1, 2018, pp. 141-170. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/elh.2018.0005, p. 141.

Poetry Foundation, Emily Dickinson. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/emily-dickinson

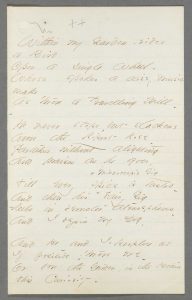

Within my Garden, rides a Bird (F370A, J500)

Within my Garden, rides

a Bird

Opon a single Wheel -

Whose spokes a dizzy music

make

As 'twere a travelling Mill -

He never stops, but slackens

Above the Ripest Rose -

Partakes without alighting

And praises as he goes,

Till every spice is tasted -

And then his Fairy Gig

Reels in remoter atmospheres -

And I rejoin my Dog,

And He and I, perplex us

If positive, 'twere we -

Or bore the Garden in the Brain

This Curiosity -

But He, the best Logician,

Refers my +clumsy eye -

To just vibrating Blossoms!

An exquisite Reply!

+duller

EDA manuscript: "Originally in Poems: Packet VI, Fascicle 18. Includes 13 poems, written in ink, dated ca. 1862. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. First published in Further Poems (1929), 59, with the alternative for line 18 adopted."

Here are the students' responses.

Zea Eanet

Emily Dickinson opens “Within my Garden Rides a Bird,” the ninth piece in Fascicle 18, with a description of a hummingbird that understands the creature by way of comparison to human objects. The bird rides upon a “single Wheel” whose “spokes” rotate with wild speed — so fast that their cutting of the air makes a noise that sounds, to the narrator, like a “dizzy music.” The language here is ambiguous – the spokes could either belong to the bird itself or more literally to the imagined wheel. In either case, the metaphor describes the bird’s wings in motion. The narrator then likens the bird to a “travelling Mill,” both stating a literal similarity of motion between the bird’s wings and the turning of a mill wheel, and also suggesting that, as in industrial mills, this rotational movement is a method of gathering energy.

Emily Dickinson opens “Within my Garden Rides a Bird,” the ninth piece in Fascicle 18, with a description of a hummingbird that understands the creature by way of comparison to human objects. The bird rides upon a “single Wheel” whose “spokes” rotate with wild speed — so fast that their cutting of the air makes a noise that sounds, to the narrator, like a “dizzy music.” The language here is ambiguous – the spokes could either belong to the bird itself or more literally to the imagined wheel. In either case, the metaphor describes the bird’s wings in motion. The narrator then likens the bird to a “travelling Mill,” both stating a literal similarity of motion between the bird’s wings and the turning of a mill wheel, and also suggesting that, as in industrial mills, this rotational movement is a method of gathering energy.

Dickinson poses the wheel, music, and the idea of industry as explanatory metaphors for what is an odd natural phenomenon: the unique locomotion of the hummingbird. Later in the poem, too, the narrator describes the hummingbird as traveling within a “Fairy Gig;” in other words requiring, as human beings do, a constructed vehicle and the labor of another (a gig was traditionally pulled by a horse) for effective transportation. The narrator’s understanding of the hummingbird, while evocative, is also incomplete and reductive, due to her inability to understand it as anything but analogous to appendages of human life.

The poem’s three characters display varying degrees of perceptive ability. Of the three — the hummingbird, the narrator, and her dog — the human is by far the least able to understand the workings of her natural surroundings, requiring metaphor to do so even imperfectly. Next comes the dog, “the best Logician” — another human metaphor — who ultimately decides to share his generous observational powers with his master, referring her “clumsy eye” to a shivering flower as proof that the brief hummingbird had truly been there. The hummingbird comes out on top, with the ability to rapidly and accurately identify the “Ripest Rose” in the garden, and such a deep knowledge of human modes of perception that it avoids leaving any discernible trace of its visit when it goes. This hierarchy of understanding is parallel to the degree of wildness of each character; the hummingbird is a wild non-human, the dog a domestic non-human, and the narrator a domestic human. The boundaries between the human world and the natural one are therefore vague, leaving the reader to ask whether the dog is a part of nature or not, an issue that ultimately calls for a redefinition, or at least reconsideration, of the concept of “nature” itself.

The garden, which is in a sense a fourth character, has a much more powerful ability than any of them. After the departure of the bird, the narrator and her dog wonder whether it was there at all — the narrator’s senses are “perplexed” by ‘"this Curiosity”— or whether the garden “bore” the vision “in the Brain.” One reading of this curious line suggests that if observation of reality is a way in which an individual can ‘bear’ things into their brains themselves, then the garden in this text has the power to override this behavior and deliver false, deceptive images directly into the minds of its viewers. This construction grants the garden agency, power over its human visitors, and a far deeper understanding of the human mind than the human mind has of it. The poem, too, shares this power and understanding, since by its nature it is image and narrative delivered by way of language into the mind of the reader, who, like the narrator, cannot determine the truth and must either accept what has been received or seek aid in investigating it.

The poem concludes in pure delight, with the narrator crying that the “vibrating” of the “Blossoms” is “an exquisite Reply!” Dickinson suggests here that though we as human beings cannot fully understand the natural world, we can — and should — nevertheless appreciate it from a position of ignorance. In fact, attempting to understand it the way Dickinson’s narrator does only serves to cloud reality further; since the poem, like the garden’s “Curiosity,” is in some sense a delivery of information to the reader, the narrator’s intervention with metaphor does not clarify, but rather obfuscates, the content that is being transmitted. This requires that the reader spend time decoding these constructs just to get at the bare bones of the narrative to discover, for example, what kind of odd industrial bird it is that flies by use of wheels and carriages. Ultimately, the poem demonstrates how viewing the world exclusively through the lens of human experience damages our ability to perceive and to comprehend the non-human, and subsequently implies that when, and only when, we remove the anthropocentric veil that shades our eyes will we be able to engage with the rest of life with unmitigated joy.

Lily Jin

“Within my Garden, rides a Bird” (F370A, J500) appears in Fascicle 18, from the fall of 1862. The poem stands in relation to a number of others in Fascicle 18, including “I tend my flowers for thee” and “It will be Summer – eventually,” primarily in terms of imagery. The poems find their roots in conventionally cultivated gardens and natural landscapes.

“Within my Garden, rides a Bird” (F370A, J500) appears in Fascicle 18, from the fall of 1862. The poem stands in relation to a number of others in Fascicle 18, including “I tend my flowers for thee” and “It will be Summer – eventually,” primarily in terms of imagery. The poems find their roots in conventionally cultivated gardens and natural landscapes.

The poem characterizes both the hummingbird and Dickinson’s dog in a spirited and playful tone, using language of industrialization to paint an untraditional picture of the natural world. The hummingbird’s mechanic movements, as well as the dog’s sensible discernment of the scene in the garden, allows for the rational, mechanic world to exist within “nature poetry.” Dickinson, though, manages still to convey the sense of thrill and delight associated with nature, gardens, and their animals while using language of the industrial revolution and its associations.

Set in the poet’s own garden, “Within my Garden, rides a Bird” recounts an idyllic moment as Dickinson describes her and her dog’s reaction to spotting the bird. The bird rides “Upon a single Wheel – / Whose spokes a dizzy Music make / as ‘twere a travelling Mill”. The poem, though, uses unconventional metaphors to paint the hummingbird’s image. The bird’s whirring motion is compared to tools of industrialization that disrupt the otherwise natural setting. Mechanical associations of the wheel and its spokes within the mill stand in contrast to the vitality of the dizzying hummingbird. “Mill” could refer to a number of energy-producing apparatuses, including a water-wheel, grindstone, windmill, roller machine, factory, or current channel (EDA). Dickinson’s phrase is left just vague enough to encapsulate all, or part, of the many mechanical units produced by the Industrial Revolution.

In its last stanza, the poem humanizes Dickinson’s dog in a humorous and amusing manner. Unsure whether the illusory hummingbird had truly visited the garden, Dickinson stands puzzled until she finds the answer to her curiosity through the motion of the dog. She admires its intelligence, as “He, the best Logician,” directs her “clumsy eye” to the flower, left vibrating after being touched by the hummingbird. Dickinson, at this point, flips the traditional relationship and dichotomy between the human and non-human animal. The dog’s perceptiveness, in this moment, surpasses that of her own. Dickinson’s classic dashes are replaced with two consecutive exclamations to end the poem. Her gaze is shifted “To just the vibrating Blossoms! An Exquisite Reply!”

Dickinson combines these unlikely metaphors in order to reconcile notions of the manufactured, man-made world and the natural one. This combination allows for innovation within the tradition of garden and nature writing, breaking down conventional barriers between culture and nature. Engaging the technological world and rational thought associated with the Industrial Revolution, Dickinson is able to uphold the relevance of garden poetry even during the cultural shift towards productivity. Using metaphors associated with her garden’s animals, Dickinson raises a new understanding of the relationship between humans and non-human animals, as well as between nature and progress. The poem counters the capitalist and consumerist ideology of the era that regarded nature poetry, or poetry in general, as fruitless, impractical, or unconnected to the world, cultivating the significance of Dickinson’s poetry as an enduring and ever-changing cultural object.

Works Cited

Emily Dickinson Archive, Lexicon. Accessed 23 April 2018.

Parker Whims

Emily Dickinson’s “Within my Garden, rides a Bird” (F370A, J500) imagines a regular garden infused by the ephemeral. The poem begins with the narrator and her dog walking through a row of plants. Then, a foreign force intrudes on them from above. The titular Bird enters “Opon a single Wheel – / Whose spokes a dizzy music / make / As ‘twere a travelling Mill” (ll. 3-6). Animals like the Bird are elevated to supernatural status throughout the poem. While the Bird rides into the Garden on a mechanical wheel, it is playing an alluring tune that evokes the siren quality of Lewis Carroll’s cats and caterpillars. The narrator’s dog also receives superhuman qualities as well. After the narrator fails to sense the Bird’s entrance, the dog notices when “He, the best Logician, / Refers my duller – clumsy eye – / To just vibrating Blossoms! / An exquisite reply!” (ll. 19-22). Though the narrator is oblivious to the Bird entering above, “the best Logician” – namely, the dog’s heightened senses – are able to pick up on the wheeled spectacle.

Emily Dickinson’s “Within my Garden, rides a Bird” (F370A, J500) imagines a regular garden infused by the ephemeral. The poem begins with the narrator and her dog walking through a row of plants. Then, a foreign force intrudes on them from above. The titular Bird enters “Opon a single Wheel – / Whose spokes a dizzy music / make / As ‘twere a travelling Mill” (ll. 3-6). Animals like the Bird are elevated to supernatural status throughout the poem. While the Bird rides into the Garden on a mechanical wheel, it is playing an alluring tune that evokes the siren quality of Lewis Carroll’s cats and caterpillars. The narrator’s dog also receives superhuman qualities as well. After the narrator fails to sense the Bird’s entrance, the dog notices when “He, the best Logician, / Refers my duller – clumsy eye – / To just vibrating Blossoms! / An exquisite reply!” (ll. 19-22). Though the narrator is oblivious to the Bird entering above, “the best Logician” – namely, the dog’s heightened senses – are able to pick up on the wheeled spectacle.

This distinction in awareness between human and animal is made even more interesting by Dickinson’s use of “Logician.” The divide between the developed mind and the animal psyche has traditionally been the ability to use logic and reason. Yet during “Within my Garden, rides a Bird,” animals and dogs show a mastery of the mechanical and the logical. The resulting comparison doesn’t speak highly of humans and their cognitive ability. Furthermore, the most definable trait given to the human narrator in this poem is control. The title proclaims the dominion of the narrator over the garden, and the setting of the poem therefore occurs entirely inside the narrator’s property. The dog is also presumably owned by the narrator. But the only other quality exerted by the narrator is fleeting wonder at the fact that the Bird “Partakes without alighting / and praises as he goes / Till every spice is tasted” (ll. 18-21) when it jumps from plant to plant in the garden. This, along with joy at the “exquisite reply!” as the dog noticed the bird earlier in the poem are the only sentiments expressed.

This element of childishness juxtaposed against control implies a sort of blind stewardship by humans. Though we consider ourselves master Logicians, Dickinson implies we are blind to the wonders above us. “Within my Garden, rides a Bird” inverts the power structure of the animal kingdom. The dog might as well be walking the narrator, and man is ignorant of the mythical Bird that lives inside his very own garden.

Steven Presbot, “A Specter in the Garden”

In Emily Dickinson’ poem “Within my Garden, rides a Bird,” the poet wanders in on an intimate scene while strolling through her garden one day with her dog. She spies a humming bird weaving in between flowers with such quick and precise flying that it seems “as ‘twere a travelling Mill.” The bird is an arbiter of nature, a species that coexists symbiotically with it, giving back just as much as it receives. It takes nourishment from each flower “till every spice is tasted,” and pollinates as he goes, leaving traces of his presence behind and ensuring future growth.

“He never stops but slackens,” moving furiously between flowers on wings that produce a“dizzy music.” The poet is entranced by the bird’s flight. It is almost magical and she later compares it to a fairy. Its presence is ephemeral, almost intangible, and before she knows it, the bird disappears into “remoter atmospheres.” It flits in and out like a friendly specter in a dream. In the briefest of moments, the poet looks into the bird’s world and observes its magic. She revels in it like a human stumbling upon a deity taking a drink of water and observing its grace. The reader gets a sense that the bird is powerful but delicate, fierce but fragile, cunning but vulnerable.

Dickinson’s poem describes the wonder and curiosity felt by gazing into the natural world, as an almost interloper. For humans, looking on nature can be like gazing into a world that we left behind long ago. As a species, we were once inextricably linked to nature, we were its offspring, but with industry and progress, we as humans have lost some of our connection to nature. Our relationship to it has always been a frail one. From the moment that we, as a species, learned to cultivate the land we went from trying to survive in it to dominating it, from a position of vulnerability to one of power. We put up fences and manipulate growth.

We move around the world as if nature is a separate element, something to be contained. In gardens we try to recreate a pastoral past, to achieve a natural symbiosis and return to the idyllic. It is because of our strained connection to the natural that the poet needs her dog’s assistance to notice the bird’s beauty. The dog helps his human in reconnecting with this “Garden in the Brain.” Animals have a stronger connection to the natural world. They see, hear, smell, and touch that which is just outside of human reach. Thus, humans need help seeing what is obvious to animals. We have what Dickinson refers to as a “clumsy eye.” It is the part of our being that we have sacrificed in order to become the dominant species. It blinds us to the part of nature that we left behind. The dog, however, is the “the best logician” because he’s closer to nature and wiser than us in that sense.

Furthermore, dogs and humans have an ancestral connection. It is a covenant made through coexistence, forged through survival, and shaped by human dominance. The dog has always been man’s most faithful companion. We have helped to shape dogs like we have shaped nature, mostly to our advantage. The poet’s dog refers her to nature’s “Exquisite Reply,” and in that moment she returns to the pastoral and reconnects with that lost part of herself.