This week our point of departure is Dickinson’s 6th and final letter (L274) to Thomas Wentworth Higginson written in 1862; they continued to correspond until the very end of Dickinson’s life. At this time, Higginson was busy recruiting and training troops from Massachusetts for the War, but in November would accept an extraordinary commission: command of the First South Carolina regiment composed of formerly enslaved men. Even though Dickinson’s letter indicates a lull in their correspondence, which began in April 1862, her exchanges with Higginson will prove to be crucial in Dickinson’s life.

This week our point of departure is Dickinson’s 6th and final letter (L274) to Thomas Wentworth Higginson written in 1862; they continued to correspond until the very end of Dickinson’s life. At this time, Higginson was busy recruiting and training troops from Massachusetts for the War, but in November would accept an extraordinary commission: command of the First South Carolina regiment composed of formerly enslaved men. Even though Dickinson’s letter indicates a lull in their correspondence, which began in April 1862, her exchanges with Higginson will prove to be crucial in Dickinson’s life.

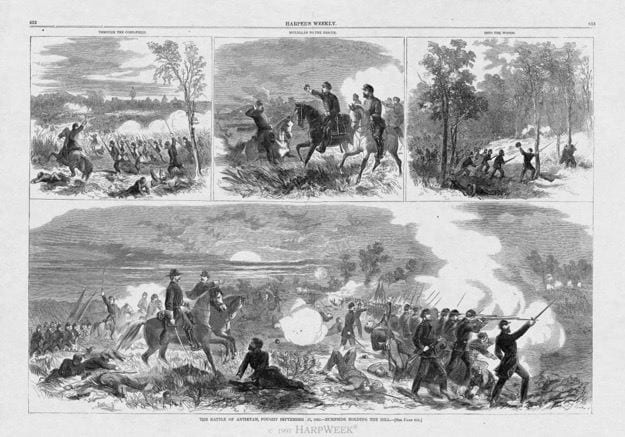

This week in 1862 saw the first extensive coverage of the Battle of Antietam, also called the Battle of Sharpsburg, which occurred on September 17, 1862. It was a decisive and deadly battle that would achieve the dubious distinction of being the bloodiest battle in US history. It also had the distinction of being one of the first battles to be extensively recorded by an emerging technology that would change the face of war journalism forever: photography. Matthew Brady sent two photographers to the battlefield who captured the battle’s horrifying aftermath. These images, in photographic exhibitions and as illustrations in print journalism, circulated widely and contributed to a new, appalling recognition—reflected in the poetry of Emily Dickinson—of just how costly this fratricidal war was. For this post, we draw on work by Sarah Khatry, Dartmouth ’17, from an assignment she did for Ivy’s “New Dickinson” junior colloquium in Winter 2017.

“The Dead of Antietam”

Springfield Republican, October 4, 1862

Progress of the War, page 1

“Another week of rest and preparation. There have been only preliminary reconnaissances towards the enemy either in Virginia or in Kentucky. But it is now evident that the enemy is checkmated and has reached the limit of his aggressive movements, and that is a great deal, when we look back a single month and see where we were then and what were our fears and forebodings.”

Books, Authors and Art, page 3

“A great rarity in the shape of coins has lately been sold at Paris—namely, a silver one struck off at Breslau in 1751. Among the persons employed at the time in the mint was an Austrian, who, out of hatred to Frederick II of Prussia, conceived the idea of revenging himself on that monarch in the following manner:—The motto on the coin, ‘Ein reichs thaler’ (a crown of the kingdom), he divided in such a manner as to make it read, ‘Ein reich stahler’ (he stole a kingdom). The king ordered those insulting coins to be melted down, but some few of them still exist.”

English Beauty, page 6

“I have heard a good deal of the tenacity with which English ladies retain their personal beauty to a late period of life; but (not to suggest that an American eye needs use and cultivation before it can quite appreciate the charm of an English beauty at any age) it strikes me that an English lady of fifty is apt to become a creature less refined and delicate, so far as her physique goes, than anything that we western people class under the name of woman. Yet, somewhere in this bulk must be hidden the modest, slender, violet-nature of a girl, whom an alien mass of earthliness has unkindly overgrown.”

Hampshire Gazette, October 7, 1862

Position of McClellan’s Army, page 1

“Gen. McClellan still had his headquarters near Sharpsburg yesterday, when Gen. Sumner occupied Boliver Heights. It is evident to us that there will be a movement on Gen. McClellan’s part as soon as his army is properly supplied by the quartermaster’s department. Our troops are in the best possible spirits, and eager again to get at the rebels, who must be suffering dreadful torments.”

Getting Rich, page 1

“Men are never richer on their millions than on their thousands or hundreds—they are never satisfied, whatever they have; they are never blessed, but always to be blessed. We start out in the world without a cent, and think, while we toil for a mere pittance, that if we had a house over our heads we could call our own, we should be independent and contented; then we want five or ten thousand dollars; and by the time that has accumulated, the expenses of living have pressed upward so fast that we must double it to keep clear of absolute want.”

Harper’s Monthly Illustrated Magazine, October 4, 1862

[from a full description of each stage of the battle of Antietam/Sharpsburg, with illustrations.] “The battle began with the dawn. Morning found both armies just as they had slept, almost close enough to look into each other’s eyes. … A battery was almost immediately pushed forward beyond the central woods, over a plowed field, near the top of the slope where the corn-field began. On this open field, in the corn beyond, and in the woods, which stretched forward into the broad fields like a promontory into the ocean, were the hardest and deadliest struggles of the day. … But out of those gloomy woods came suddenly and heavily terrible volleys—volleys which smote, and bent, and broke in a moment that eager front, and hurled them swiftly back for half the distance they had won. Not swiftly, nor in panic, any further. Closing up their shattered lines, they came slowly away—a regiment where a brigade had been, hardly a brigade where a whole division had been, victorious. They had met from the woods the first volleys of musketry from fresh troops—had met them and returned them till their line had yielded and gone down before the weight of fire, and till their ammunition was exhausted. …The field and its ghastly harvest which the reaper had gathered in those fatal hours remained finally with us. Four times it had been lost and won. The dead are strewn so thickly that as you ride over it you can not guide your horse’s steps too carefully. Pale and bloody faces are every where upturned. They are sad and terrible, but there is nothing which makes one’s heart beat so quickly as the imploring look of sorely wounded men who beckon wearily for help which you can not stay to give.”

“The battle began with the dawn. Morning found both armies just as they had slept, almost close enough to look into each other’s eyes. … A battery was almost immediately pushed forward beyond the central woods, over a plowed field, near the top of the slope where the corn-field began. On this open field, in the corn beyond, and in the woods, which stretched forward into the broad fields like a promontory into the ocean, were the hardest and deadliest struggles of the day. … But out of those gloomy woods came suddenly and heavily terrible volleys—volleys which smote, and bent, and broke in a moment that eager front, and hurled them swiftly back for half the distance they had won. Not swiftly, nor in panic, any further. Closing up their shattered lines, they came slowly away—a regiment where a brigade had been, hardly a brigade where a whole division had been, victorious. They had met from the woods the first volleys of musketry from fresh troops—had met them and returned them till their line had yielded and gone down before the weight of fire, and till their ammunition was exhausted. …The field and its ghastly harvest which the reaper had gathered in those fatal hours remained finally with us. Four times it had been lost and won. The dead are strewn so thickly that as you ride over it you can not guide your horse’s steps too carefully. Pale and bloody faces are every where upturned. They are sad and terrible, but there is nothing which makes one’s heart beat so quickly as the imploring look of sorely wounded men who beckon wearily for help which you can not stay to give.”

“You Saved my Life”

Dickinson’s plaintive letter to Higginson this week (L274) indicates her increasing dependence on their epistolary relationship and her ostensible desire to “please” him. In fact, Dickinson usually argued with and ultimately ignored Higginson's advice on her writing. But as a figure in and of the world of letters and actions, he provided her with an important and invaluable contact. In a letter from June 1869, she confessed to him:

Of our greatest acts we are ignorant –

You were not aware that you saved my Life. (L330)

Still, it is no wonder that Higginson did not have time to write to Dickinson in the Fall of 1862. She last wrote to him in response to his letter sometime in August. By October 6th, she had not gotten a response from him and penned her plaintive inquiry. According to historian Ethan Kytle, during the fall, Higginson

was recruiting and then training boys from his adopted hometown of Worcester, Mass., to serve in the [Massachusetts] 51st. . . . After declining an officer’s commission in the early months of the Civil War, the 38-year-old Transcendentalist minister had decided that if “antislavery men” expected to influence the conduct and settlement of the conflict, then they “must take part in it.”

He thus accepted a commission as a captain and wrote in a letter about this company that he “already loved [them] like my own children.”

In a month, though, Higginson would be offered the command of the 1st Regiment of South Carolina Volunteers, which was comprised of formerly enslaved men. According to Sage Stossel,

The preliminary Emancipation Proclamation announced by President Lincoln in September 1862 allowed the Union army to recruit blacks. … [Higginson] kept a diary of the experience, which was later excerpted in The Atlantic as “Leaves From an Officer’s Journal” (1864) and subsequently released as a book, Army Life in a Black Regiment.

Meanwhile, newspapers and journals began their detailed coverage of the horrific battle of Antietam. Because of the rather long news cycle (certainly longer than ours), this coverage would continue well into December. As Sarah Khatry notes: “The farther from the event itself, the closer and more detailed the coverage became.” In her exploration of this event in Dickinson’s life, Sarah focused

not so much on the immediate events of the Civil War during that week, but on their transmission and how Emily Dickinson would have encountered them … Through image—photograph and illustration—through prose—news, letters, narratives—and through personal connection.

From the coverage in Harper’s, we can infer that illustrations, often based on the new technology of photography, played a large role.

In fact, two days after the battle, Matthew Brady sent Alexander Gardner and James Gibson to Maryland to photograph the aftermath of the bloodiest battle in US history. A month later, Brady set up an exhibit of almost 100 pictures in his gallery on Broadway in New York City called, simply, “The Dead of Antietam.” The photographs were so sharp, viewers could make out faces, and so unfiltered as to bring the effects of the war, before remote and abstract, into unmistakable focus for the first time. Some of the illustrations Dickinson might have seen in Harper’s were based on Brady’s gut-wrenching photographs.

Reflection: “Trauma and the Image”

Sarah Khatry

The real-time scholarly project of White Heat invites not only engagement with the week-by-week experience of Emily Dickinson’s life in 1862, but juxtaposition with our own. This past week seems an appropriate one to reflect upon the real and traumatic individual impact of nationwide events, even those transmitted to us only through image.

The real-time scholarly project of White Heat invites not only engagement with the week-by-week experience of Emily Dickinson’s life in 1862, but juxtaposition with our own. This past week seems an appropriate one to reflect upon the real and traumatic individual impact of nationwide events, even those transmitted to us only through image.

The modes and means of transmission have changed. As this week’s poems demonstrate, Dickinson experienced the Civil War and particularly the battle of Antietam through the personal impact on her family and community, the vivid magazine and newspaper reporting of the day, and also the then-developing technology of photography.

It was not Death, for I stood up,

And all the Dead, lie down -

It was not Night, for all the Bells

Put out their Tongues, for Noon.

It was not Frost, for on my Flesh

I felt Siroccos – crawl -

Nor Fire – for just my marble feet

Could keep a Chancel, cool -

And yet, it tasted, like them all,

The Figures I have seen

Set orderly, for Burial

Reminded me, of mine -

As if my life were shaven,

And fitted to a frame,

And could not breathe without a key,

And ’twas like Midnight, some -

When everything that ticked – has stopped -

And space stares – all around -

Or Grisly frosts – first Autumn morns,

Repeal the Beating Ground -

But most, like Chaos – Stopless – cool -

Without a Chance, or spar -

Or even a Report of Land -

To justify – Despair.

(F 355)

In her essay, “Death’s Surprise, Stamped Visible,” Eliza Richards draws upon the poem above, finding in the third stanza a rather direct description of a famous photograph by Andrew Gardner and James Gibson of the bodies after the Battle of Antietam: “The Figures I have seen / Set orderly, for Burial”.

I will attempt to take this reading further, and argue an even stronger correlation. In the first two stanzas, Dickinson establishes a multi-fold disconnect between the experience the poem describes and the speaker’s subjectivity. “It was not Death” because the speaker is on her feet, not dead, and whatever it is she contemplates is not death itself, but something like it. That object or experience is also at a remove in time for her, for she hears the bells tolling noon, but she must remind herself it is not night. The sensory experience being conveyed, as described in the second stanza, is similarly disassociated from the speaker—

I will attempt to take this reading further, and argue an even stronger correlation. In the first two stanzas, Dickinson establishes a multi-fold disconnect between the experience the poem describes and the speaker’s subjectivity. “It was not Death” because the speaker is on her feet, not dead, and whatever it is she contemplates is not death itself, but something like it. That object or experience is also at a remove in time for her, for she hears the bells tolling noon, but she must remind herself it is not night. The sensory experience being conveyed, as described in the second stanza, is similarly disassociated from the speaker—

And yet, it tasted, like them all (l. 5)

These first two stanzas could describe the experience of standing before a photograph, one of such power and visceral empathy that the speaker has to repeatedly emphasize to herself that she is not there. She is not one of “The Figures … Set orderly, for Burial.” It is not her life “shaven, / and fitted to a frame” but the lives she considers, quite possibly those belonging to the dead of Antietam.

In the word “Autumn” (l. 19), Richards finds phonetic similarity with Antietam, driven home by Dickinson’s poem below, evocative of the massacre and excess of a battlefield:

The name — of it — is “Autumn” —

The hue — of it — is Blood —

An Artery — upon the Hill —

A Vein — along the Road —

Great Globules — in the Alleys —

And Oh, the Shower of Stain —

When Winds — upset the Basin —

And spill the Scarlet Rain —

It sprinkles Bonnets — far below —

It gathers ruddy Pools —

Then — eddies like a Rose — away —

Upon Vermilion Wheels —

(F 465)

No New England fall, I believe, clamors for such blood-filled celebration. But Antietam occurred in mid-September, the advent of autumn, and its traumatic bloodshed, spilling as if from an “Artery — upon the Hill,” traveled up the Veins, the roads, of the nation, spilled into alleyways and sprinkled Bonnets far from the battlefield.

The speaker in “It was not Death” feels, by the final line, despair. The figures set for burial are frozen equally by death and by the photographic medium. They are “Without a Chance, or spar – / or even a Report” (ll. 22-23), paralyzed and mute, unable to give voice or justification to the despair of the speaker.

It can feel almost without justification to despair over the trauma of a distant stranger. But in moments of national crisis and discord, the trauma comes home to the individual, if not in the form of a direct parallel experience, but in the mirror of empathy. We have seen that in recent events. During the day of testimony by Dr. Christine Blasey Ford last week, the RAINN sexual assault hotline saw a 147% increase in calls, according to Abigail Abrams.

Far different events, more immediate modes of transmission, new lines of division … but still we and Emily Dickinson’s speaker must remind ourselves it was not me, and reconcile the reality of what did transpire, and to whom, and what it means.

Sources

Abrams, Abigail. “National Sexual Assault Hotline Spiked 147% During Ford Hearing.” Time, 27 Sept. 2018.

Richards, Eliza. “‘Death's Surprise, Stamped Visible’: Emily Dickinson, Oliver Wendell Holmes, and Civil War Photography.” Amerikastudien 54.1 (2009): 13-33, 27.

Bio: Sarah Khatry received a BA in physics and English from Dartmouth College in 2017. Her novella Ritual won the Sidney Cox Memorial Prize in 2015. Her nonfiction appears in 40 Towns, the Dartmouth, and elsewhere.

Sources

History

Hampshire Gazette, October 7, 1862

Harper's Monthly, October, 1862

Springfield Republican, October 4, 1862

Biography

Khatry, Sarah. “December 7-14: A Nation Infused by Trauma.” Assignment for Eng 62. Dartmouth College. Winter 2017.

Kytle, Ethan J. “Captain Higginson Takes Command.” The Opinionator: A Gathering of Opinion from Around the Web. November 16, 2012.

Higginson, Thomas Wentworth. “Leaves from an Officer’s Journal.” Introduced by Sage Stossel. Atlantic Monthly 1864.