On Choosing the Poems

Some readers regard the self-abasement in the Third “Master Document” as part of an SM scenario, the sentimental pleasures of submission that elicit the full erotic self. But the Daisy’s address to Master operates across many emotional and imagistic registers that complicate the binary of Master-daisy or the Victorian era’s requirement of female submission. Páraic Finnerty offers the novel Jane Eyre (1847) by Charlotte Brontë, one of Dickinson’s favorites authors, as a source for the explosive energies of this document.

He argues that women readers like Dickinson were attracted by “its heroine’s acquirement of the economic and external resources to complement her inner liberty,” a liberty that made possible the ultimately “nonhierarchical relationship” of Jane and Rochester. “Dickinson drew on such ideas to construct and unsettle hierarchical relationships between the sexes in her hyperbolic ‘Master’ letters,” he concludes.

In summing up approaches to poems concerned with the “Other” and the “Master,” especially Mary Loeffelholz’s chapter “Love After Death” (in Dickinson and the Boundaries of Feminist Theory), Roland Hagenbüchle observes:

What has been clarified through such painstaking exegesis is the span of alternatives, but such clarification has only deepened the problem, if anything. Is the “Master” a biographical person? And if so, who is it? Is it really the same person in each of these poems? Or is it perhaps the soul’s “Oversoul” [Emerson’s term for a supreme reality or spiritual unity of all being]? The mind’s male animus? The self’s creative alter ego? Is it (in some sense) Christ or Dickinson’s appropriation of Christ? The looked for and always desired but infinitely deferred “Other”? A messenger of Eros or of Thanatos – or both? All we can safely say is that the “Master” stands for what the lyric self lacks, desires, and fears. Biographical, psychological, cultural and existential aspects converge in this evasive figure.

One contemporary response brings the Master-daisy dynamic into the 21st century. Lucie Brock-Broido’s volume of poetry, The Master Letters (1995), opens with an image of the first manuscript page of the Third “Master Document.” She describes her poems as “a series of latter-day Master Letters, [that] echo formal & rhetorical devices from Dickinson’s work,” what she calls, “her brocade devastations.” For Brock-Broido, Dickinson’s three Master documents

maintain the lyric density, the celestial stir, her high-pitched cadences, her odd Unfathomable systems of capitalization, the peculiar swooning syntax, the fluid stutter of her verse.

The following poems are among the many that reflect themes related to issues of mastery explored in the post for this week.

Poems for the Week of January 15-21, 1862: Mastery

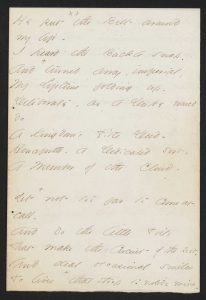

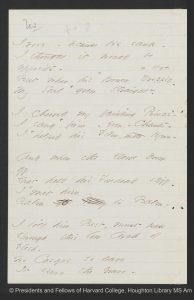

He put the Belt around my life – (F 330, J 273)

He put the Belt around

my life –

I heard the Buckle snap –

And +turned away, imperial,

My Lifetime folding up –

Deliberate, as a Duke would

do

A Kingdom's Title Deed –

Henceforth – a Dedicated sort –

A Member of the Cloud –

+Yet not too far to come at

call –

And do the little Toils

That make the Circuit of the Rest –

And deal occasional smiles

To lives +that stoop to notice mine –

And kindly ask it in –

Whose invitation +know you not

For Whom I must decline?

+ And left his process – Satisfied +Yet near enough

+ As stoop + For this world –

EDA manuscript: "Originally in: Packet XIV, Mixed Fascicles, written in ink, ca. 1860-1862. First published in Poems (1891). Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA."

The word “Master” does not occur in this poem, but the speaker attributes many of the characteristics of power and domination to the “He” who snaps the belt around her life. He is “imperial,” like a “Duke” handling “a Kingdom’s Title Deed.” Marianne Noble observes:

Evident in Emily Dickinson’s writing is a strain of masochistic expression, as the first lines of many poems (“Bind me, I still can sing”; “Joy to have merited the pain”; “He put the belt around my life / I heard the Buckle snap”) and countless other phrases (“Most I love the cause that slew me,” “a Bliss like Murder,” “an ecstasy of parting / denominated Death”) suggest.

Noble connects this masochistic strain to Dickinson's letters, especially the Master documents. But is this belt a wedding ring, or a sign of spiritual vocation, like “The Collar” of a priest or minister that gives the title to a poem by George Herbert (1593-1633) about his resistance to his religious calling? Or is it a sign of artistic calling that binds the speaker to a powerful Muse figure and keeps her separate from ordinary society? Or all three?

Joan Kirkby finds many analogues in the periodicals Dickinson read for what Kirkby calls her “bride poems,” including “poems of sacrifice and loss, compromised autonomy and early death,” and this unmistakable assertion from an essay in The Springfield Republican on January 25, 1845:

Marriage is to woman at once the happiest and the saddest event of her life; it is the promise of future bliss raised on the death of all present enjoyment.

Kirkby argues that Dickinson avoids the “pathos” of these representations and “ironizes the limited gender roles assigned to women in her culture” in poems like “He put the Belt around my life,” in which “marriage is a kind of colonization of the bride.”

Helen Vendler offers folktale’s “Cinderella” as a backdrop for the insignificant girl who is “hidden royalty,” but also hears an echo of the moment of spiritual and artistic vocation experienced by the English Romantic poet William Wordsworth (1770-1850) in the speaker’s self-description as “a Dedicated sort”:

I made no vows, but vows

Were then made for me; bond unknown to me

Was given, that I should be, else sinning greatly,

A dedicated Spirit.The Prelude (1850) IV, 334-337

Vendler observes:

We meet, in this poem, four Dickinsons: the humble one doing “little Toils” in the routine “Circuit” of the Household; the spiritual “Member of the Cloud” who has business with a celestial Realm; the hidden Duchess who deals out royal smiles; and the poor spinster whom others take pity on, thinking that she needs invitations. Nobody understands her declining of those invitations, because they cannot see the imperial power to whom she belongs.

Formally, Vendler notes, the poem consolidates its four rhymed quatrains into two eight-line stanzas “to demonstrate the two lives that the poet lives.”

Sources

Kirkby, Joan. “Periodical Reading.” Emily Dickinson in Context. Ed. Eliza Richards. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013. 139-47.

Noble, Marianne. "The Revenge of Cato's Daughter: Dickinson's Masochism." The Emily Dickinson Journal, 7(2. Fall) 1998.

Vendler, Helen. Dickinson: Selected Poems and Commentaries. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University, 2010, 135-37.

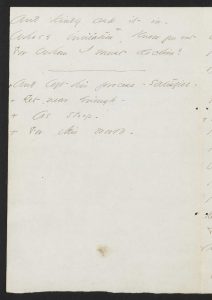

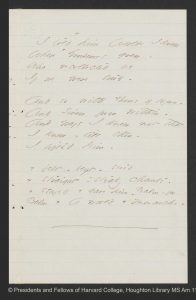

Doubt me! My dim companion! (F332A J 275)

Doubt Me! My Dim Companion!

Doubt Me! My Dim Companion!

Why, God, would be content

With but a fraction +of the Life –

Poured thee, without a stint –

The whole of me – forever –

What more the Woman can,

Say quick, +that I may

dower thee

With +last Delight I own!

It cannot be my spirit –

For that was thine, before –

I ceded all of Dust I knew –

What Opulence the more

Had I – a freckled Maiden

Whose farthest of Degree,

Was – that she might –

Some distant Heaven,

Dwell timidly – with thee !

Sift her, from Brow to Barefoot!

Strain till your last Surmise –

Drop, like a Tapestry, away,

Before the Fire's Eyes –

Winnow her finest fondness –

But hallow just the snow

Intact, in Everlasting flake –

Oh, Caviler, for you!

+ Of the Love – +so I can – + least Delight

EDA manuscript: "Originally in Packet XIV, Mixed Fascicles, written in ink, ca. 1860-1862. First published in Poems (1890), stanzas 1 and 2, with the alternative for line 3 adopted. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA."

This address to a “doubting” lover reprises language in the Third Master document. It identifies the speaker as “a freckled Maiden” with a dowry of “Delight,” who had “ceded” all her spirit to the lover who doubts her, and wishes simply to “Dwell timidly” with this lover. The final stanza complicates this simplicity with stronger images of “surmise,” “fire,” and “just the snow / Intact, in Everlasting flake,” and strong verbs like “sift,” “strain,” “winnow,” “hallow.” The final epithet for the lover is “Caviler,” a strong word that, according to Dickinson’s 1844 Webster’s Dictionary, means “one who is apt to raise captious objections,” that is, find fault or ensnare in criticism. Dickinson used this word only once more, as a variant in “Whoever disenchants” (F1475A, J1451), a poem dated to 1878 .

Cynthia Wolff finds the poem’s most notable aspect to be “the speaker’s command over a supple series of verbal attitudes in her wooing of the ‘Caviler’ who has raised suspicions about her sincerity.” She observes that like other love poems, this one draws on Biblical language, specifically from the conclusion of the Book of Proverbs, “the quintessential Old Testament description of a good wife, thereby providing the appropriately conclusive rebuke to the speaker’s doubting consort:”

Who can find a virtuous woman? for her price is far above rubies. The heart of her husband doth safely trust in her. … she is not afraid of the snow for her household. … She maketh herself coverings of tapestry. (Proverbs 31:10-11, 21-22).

This language, Wolff asserts, becomes explicitly sexual and

moves into an attitude of frank invitation. … There is playfulness in this poem, but no coyness; and the bold blasphemy in the notion of Revelation is used in other love poems with the same sure tone of wonder and ecstasy.

Indeed!

Sources

Hallen, Cynthia, ed. Emily Dickinson Lexicon. Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University.

Wolff, Cynthia. Emily Dickinson. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co., Inc. 1988, 381-82.

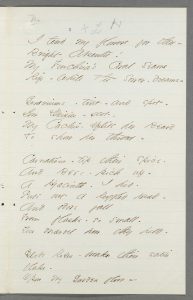

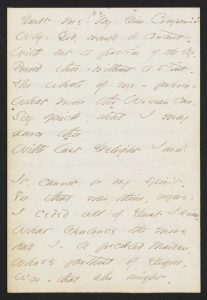

I tend my flowers for thee – (F 367, J 339)

I tend my flowers for thee –

Bright Absentee!

My Fuschzia's Coral Seams

Rip – while the Sower – dreams –

Geraniums – tint – and spot –

Low Daisies – dot –

My Cactus – splits her Beard

To show her throat –

Carnations – tip their spice –

And Bees – pick up –

A Hyacinth – I hid –

Puts out a Ruffled Head –

And odors fall

From flasks – so small –

You marvel how they held –

Globe Roses – break their satin

flake –

Opon my Garden floor –

Yet – though - not there –

I had as lief they bore

No crimson – more –

Thy flower – be gay –

Her Lord – away!

It ill becometh me –

I'll dwell in Calyx – Gray –

How modestly – alway –

Thy Daisy –

Draped for thee!

EDA manuscript: "Originally in: Packet VI, Fascicle 18, written in ink, dated ca. 1862.

First published in London Mercury, 19 (February 1929), 353-54. Courtesy of the Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA."

Richard Sewall connects this poem with the Master documents in his extended consideration of Samuel Bowles as the man Dickinson addressed as “Master.” Instead of being dated to “early 1862,” he speculates that the poem might have been written soon after Bowles left for Europe in April, recording Dickinson's sadness at the absence of her “Lord.”

Dickinson developed an extended discourse on flowers in her writing. This is not surprising, since, as Paula Bennett observes, most middle-class women of the time occupied themselves in care and cultivation of flowers. Dickinson’s father built a greenhouse off his library in which she cultivated exotic specimens and which has now been reconstructed at the Homestead, and she and her mother and sister worked in their gardens outdoors in summer.

Dickinson often included a single bloom in the many letters she wrote, as in Letter 253 to Mary Bowles discussed above. Flowers brought her close to heaven; in a letter to a friend, she wrote,

Expulsion from Eden grows indistinct in the presence of flowers so blissful, and with no disrespect to Genesis, Paradise remains (L 523).

Bennett finds approximately 400 references to flowers or their parts in Dickinson’s poems, and notes the importance of Dickinson calling herself “Daisy.” She also calls attention to the figurative use that Dickinson and other writers of the period made of flowers, to encode

references to poetry and the poetic process, to individuals and generic human beings, to Jesus and the soul, to Eden and bliss, and, perhaps most important, to woman and the female genitalia, so these images substantially contribute to the notorious ambiguity of her writing.

Cynthia Wolff connects this poem to the love poem discussed previously, “Doubt me! My dim companion!” (F332A J 275). Here, she says,

when the beloved is gone, the speaker’s garden vividly reflects her sexual frustration.

Sharon Harris goes further:

What is particularly confusing in this poem, which suggests both allurement and rape, is that “Her Lord” is away; he is endowed with an almost omniscient ability to violate her dream state through a silence of removal.

Sources

Bennett, Paula. “Flowers.” An Emily Dickinson Encyclopedia. Ed. Jane Donahue Eberwein. Westport, CT.: Greenwood Press, 1998: 115-16.

Harris, Sharon. “‘The Cloth of Dreams’: Dream Imagery in Dickinson’s Poetry and Prose.” Dickinson Studies. 68 (1988): 3-16.

Sewall, Richard. The Life of Emily Dickinson. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1980, 526-27.

Wolff, Cynthia. Emily Dickinson. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co., Inc. 1988, 382.

Sunset at Night – is natural – (F 427, J 415)

Sunset at Night – is natural –

But Sunset on the Dawn

Reverses Nature – Master –

So Midnight's – due – at Noon –

Eclipses be – predicted –

And Science bows them in –

But do One face us

suddenly –

Jehovah's Watch – is wrong –

EDA manuscript: "Originally in Packet XXXII, Mixed Fascicles, written in ink, ca. 1862. First published in Todd, Total Eclipses of the Sun (1894), lines 5-6, as an epigraph, and Further Poems (1929) entire. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA."

We have included this poem because it explicitly connects “Master” with God, referred to as “Jehovah,” with a loss of faith in God, and with Science, all large themes that will be taken up in more detail in subsequent posts.

What happens when we are faced with an emotional or spiritual “eclipse,” the obscuring of one heavenly body by the other, that defies

prediction and explanation, even by science? Terry Blackhawk notes that

Dickinson drew on scientific and technical vocabulary to a greater extent that other poets of her time,

that she had read widely in science at Amherst Academy and Mount Holyoke Seminary, and was profoundly influenced by the work of Edward Hitchcock, chair of chemistry and natural history at Amherst College and eventually its president from 1845-1854, who described himself as Amherst’s “geological theologian.”

Still, Dickinson was skeptical about science, satirizing its narrowness and dryness. “Scientific dogma pales against poetic epiphanies,” Blackhawk concludes, a notion captured by Dickinson’s startling phrase from this poem: “Jehovah’s watch – is wrong.”

Cynthia Wolff associates this poem with the doubt and loneliness Dickinson felt after 1856, when her beloved brother Austin finally accepted conversion during the raft of religious revivals that swept through Amherst and surrounding areas.

From the time she attended Mount Holyoke Seminary and was proselytized by its redoubtable headmistress, Mary Lyon, Dickinson refused to be “born again.”

About her family Dickinson said in a letter to Thomas Wentworth Higginson,

They are religious, except me, and address an eclipse, every morning, whom they call their “Father.” (L 261).

Sources

Blackhawk, Terry. “Science.” An Emily Dickinson Encyclopedia. Ed. Jane Donahue Eberwein. Westport, CT.: Greenwood Press, 1998: 259.

Wolff, Cynthia. Emily Dickinson. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co., Inc. 1988, 149.

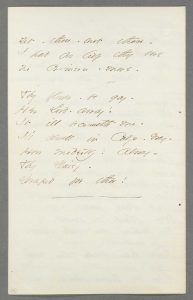

I Rose – because he sank (F454A, J616)

I rose – because He sank –

I thought it would be

opposite –

But when his power dropped –

My Soul grew straight.

I cheered my fainting Prince –

I sang firm – even – Chants –

I helped his Film – with Hymn –

And when the Dews drew

off

That held his Forehead stiff –

+I met him –

+Balm to Balm –

I told him Best – must pass

Through this low Arch of

Flesh –

No Casque so brave

It spurn the Grave –

I told him Worlds I knew

Where Emperors grew –

Who recollected us

If we were true –

And so with Thews of Hymn –

And Sinew from within –

And ways I knew not that

I knew – till then –

I lifted Him –

+ gave him + Balm for Balm

EDA manuscript: "Originally in: Poems: Packet XXXIV, Fascicle 21, written in ink, ca. 1862. First published in Atlantic Monthly, 143 (March 1929), 327, and Further Poems (1929), 93, with stanzas 2 and 3 omitted and stanza division not retained. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA."

This poem addresses power imbalances across a number of relationships. Several critics, including feminist critics, offer Charlotte Brontë's novel, Jane Eyre as a background (see the discussion of this in "On Choosing the Poems" for this week). Wendy Martin, for example, asserts:

In addition to being a direct response to the novel, this poem describing Jane’s increasing strength and control is a paradigm for Emily Dickinson’s emotional growth in general.

Other readers see the poem as describing Dickinson’s increasing poetic confidence and the development of her relationship to her Muse.

This poem can be compared to a later poem, dated to 1864, with a similar opening line:

She rose to his Requirement –

dropt

The Playthings of Her Life

To take the honorable

Work

Of Woman, and of Wife – (F857A, J732)

Still others read this poem in a religious light. Cynthia Wolff argues that as long as

God’s legend on earth remained strong, Dickinson could forge a poetic Voice of immense power by juxtaposing it against the force of the Divinity.

But the “fading of God’s presence,” which Wolff argues could already be felt in Amherst in 1862 and was further exacerbated by the devastation of the Civil War,

is a unique impediment to the poet’s efforts to assert eye/I. Thus one response to God’s decline is a remarkable effort to revive Him,

embodied in this poem.

Wolff points out the series of reversals in the poem: the speaker’s “phallic rectitude” and final “erection:” “I lifted Him – ”. In stanzas four and five the speaker quotes Jesus’s own word from Matthew 7:13-14:

Enter ye in at the strait gate: for wide is the gate, and broad is the way, that leadeth to destruction, and many there be which go in thereat: Because strait is the gate, and narrow is the way, which leadeth unto life, and few there be that find it.

Another Biblical echo resonates in the word “Sinew,” which evokes the place of Jacob’s injury when he wrestled with the Angel.

Sources

Martin, Wendy. “Emily Dickinson.” Columbia Literary History of the United States. Ed. Emory Elliott. New York: Columbia University Press, 1988: 609-26.

Wolff, Cynthia. Emily Dickinson. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co., Inc. 1988, 454.

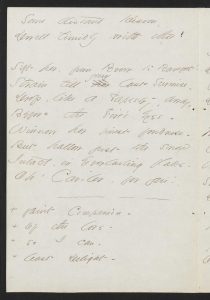

The Himmaleh was known to stoop (F460, J48)

The Himmaleh was known

The Himmaleh was known

to stoop

Unto the Daisy low –

Transported with Compassion

That such a Doll should

grow

Where Tent by Tent – Her Universe

Hung Out it's Flags of Snow –

EDA manuscript: "Originally in: Packet XIX, Fascicle 22, written in ink, dated ca. 1862 on page with "Why do I love" you, sir? (F459A). First published in Unpublished Poems (1935), 66. Poems (1955), 369. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA."

In Fascicle 22, this poem is preceded by “‘Why do I love’ You, Sir?” (F459A, J480), the last stanza of which is visible on the manuscript image above. In that poem, the speaker compares her beloved to the “sunrise” and answers the opening question with, “The sunrise – Sir – Compelleth / Me–”. A different scenario plays out in this poem, in which the giant mountain “stoops” to the low Daisy, although Richard Sewall still sees here

the same attitude of humble devotion that “Daisy” adopts towards her “Master,” “Lord,”or (by implication) “king” in the Master letters.

Arresting is the word “Doll.” According to the 1844 Webster’s Dictionary, it derives from the word for “form, image, resemblance, an idol, a false god.” The definition given is “A puppet or baby for a child; a small image in the human form, for the amusement of little girls.” The rhymes of “low” and “grow” connect Daisy and Doll, but both are also linked to “universe,” a word implying vastness, and are the references for “it’s [sic] Flags of Snow,” a reference to winter and whiteness.

One more arresting connection to “Doll.” In theorizing Dickinson’s Gothicism (discussed in last week’s post), Daneen Wardrop uses Sigmund Freud’s theory of the uncanny, which he based on a reading of E. T. A Hoffmann’s story, “The Sandman.”

This story features a life-like mechanical doll called Olympia, which later feminist theorists understand as a figure of the fetishized and subordinated woman under patriarchy.

Sources

Sewall, Richard. The Life of Emily Dickinson. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1980, 525.

Wardrop, Daneen. Emily Dickinson's Gothic: Goblin with a Gauge. University of Iowa Press, 1996.

Two important related poems not dated to circa 1862:

- My life had stood – a Loaded Gun (F764A, J754)

- Split the lark and you’ll find the music (F905A, J861)