On Choosing the Letter and Poems

Dickinson wrote may poems about travel and exotic places that illustrate what Li-Hsin Hsu calls “her spatial imagination” and her “geo-poetics.” Because we explored that theme in an earlier post, we focus here on poems about mobility and what mobility means to a poet who was relatively immobile for most of her life, certainly in the year of 1862, and tied to a particular place.

What we find is that mobility is a form of nourishment, “aliment” Dickinson calls it in one of the poems in this week’s cluster, the air that maintains life, a life-line. And she often accessed mobility imaginatively and vicariously, through the mobility of others. To illustrate this connection, we begin with a letter Dickinson’s wrote to Samuel Bowles, away on his health-improving travels in Europe. Although this letter is dated to early 1862, it sheds light on what his friendship meant to Dickinson, especially his masculine privilege of mobility. The other poems in this group illustrate, in different registers and through themes as varied as love and death, the need for flight and mobility, the ability to “circumnavigate a world of possibilities” and to accentuate the “relativity of perspectives and limitation of perception” in order to show “how the visual dominance that characterizes the exploratory narrative, transcendental philosophy and Enlightenment discourses of her time can be revised and reversed.”

To Mr. Samuel Bowles

[early 1862]

Dear friend.

If I amaze[d] your kindness – My Love is my only apology. To the people of "Chillon" – this – is enoug[h] I have met – no othe[rs.] Would you – ask le[ss] for your Queen – M[r] Bowles?

Then – I mistake – [my] scale – To Da[?] 'tis daily – to be gran[ted] and not a "Sunday Su[m] [En]closed – is my [d]efence –

[F]orgive the Gills that ask for Air – if it is harm – to breathe!

To "thank" you – [s]hames my thought!

[Sh]ould you but fail [at] – Sea -

[In] sight of me -

[Or] doomed lie -

[Ne]xt Sun – to die -

[O]r rap – at Paradise – unheard

I'd harass God

Until he let [you] in!

Emily.

Letter: Link to Yale ms.

Thomas Johnson’s note:

Ink. Outside edges torn away. Unpublished except for poem, which is in Poems (1955), 162, and there dated 1861. There can be no exact date assigned. Here the letter is moved somewhat ahead, since the letter seems to be part of a sequence that ED wrote Bowles between January and early April, when he sailed for Europe.

Poem: Link to EDA manuscript. Originally in Letter to Samuel Bowles, p. 2, Library ID: YCAL MSS 201. Courtesy of Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Library, Yale University, New Haven CT.

While Johnson dates this letter to early 1862, it is tempting to connect it to Bowles’s travel in Switzerland in the Fall, since “Chillon” refers to a castle on Lake Geneva, which also served as a prison in the 16th century during the Wars of Religions. Lord Byron wrote a famous poem, “The Prisoner of Chillon,” (1816), which Dickinson knew and referred to several times in her letters (see L293, for example).

Eleanor Heginbotham notes that “Chillon became a metaphor for Dickinson” who was deeply touched by “the anguished situation of the prisoner who, tied to a post, watches his brothers die one by one,” as described in the poem. That detail might help us glimpse the fear concealed beneath the bantering and flirtatious tone and the coded language Dickinson adopted with Bowles, as if she designed allusions for his eyes only. He has done her some kindness, sent her something for which she is thankful. She represents herself like “the people of Chillon,” an immobilized prisoner, but also as a Queen. The most arresting line is the image of “Gills that ask for Air,” as if she is an underwater creature and Bowles represents a veritable life line to her.

Dickinson's “defense” is her love for him expressed by the poem she encloses. With a comic, familiar tone, the poem associates Bowles or the beloved with the sea (travel) and other far-away places like the desert and Heaven, but also with danger–of drowning or dying of thirst, or the spiritual death of not getting into Heaven. This puts the speaker in the position of protector, savior, and intercessor with God. The almost rhyme of “Paradise” and “harass God” clinches the teasing mood. But beneath the fun, do we hear lurking fears that Bowles might not return?

Sources

Heginbothan, Eleanor. “Emily Dickinson’s Epistolary Book Club.” Reading Emily Dickinson's Letters: Critical Essays. Eds. Jane Donahue Eberwein and Cindy MacKenzie. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2009: 126-60, 137-38.

Me, change! Me, alter!

Then I will, when on

the Everlasting Hill

A Smaller Purple grows –

At Sunset, or a lesser

glow

Flickers opon Cordillera –

At Day's superior close!

Link to EDA manuscript. Originally in Amherst Manuscript # 281 – Me, change! Me, alter! – asc:12986 – p. 1. Courtesy of Amherst College, Amherst, MA. First published in Bolts of Melody (1945), 147, with the first three words of line 2 as the last of line 1.

This short, free verse “response” poem adopts a strategy we see elsewhere in Dickinson’s poetry: it responds to something someone says to the speaker off stage, so to speak, that we do not hear but can guess from the poem, and it agrees to do something in order to show the impossibility of that doing. In this case, someone has raised the possibility that the speaker will “change” or “alter,” presumably in her feelings for something or someone, and the speaker indignantly protests. But to illustrate the power of her resolve, she says, yes, I will change, but only when the unchangeable happens.

Her image of unchangeability comes from nature, specifically the sunset over the mountains. This seems like a fairly straightforward image, but it is quite layered in Dickinson’s world. Purple was a color Dickinson associated with Bowles. “Cordillera” is Spanish for mountain but most likely refers to the mountain range in the Andes made famous at the time in a painting by Frederic Church (1826-1900), a central figure in the Hudson River School of American landscape painting, known for his massive, detailed and dramatic paintings and panoramic views. According to Judith Farr, Church’s "The Cordilleras: Sunrise" (1854) established his reputation as a painter of Edenic places in the US and in South America.

While Dickinson’s poem envisions sunset over the Cordilleras, Farr asserts: “his colors are hers.” Another poem from this period, “We see – Comparatively –” (F534 c. 1863), links Cordillera with sunrise. It is important to note that Church depicts the snow-covered peak of Chimborazo, an active volcano mentioned both by Dickinson and Emerson, in the left side of his painting, its icy peak a fascinating antithesis to the towering palm tree on the right and the peaceful lake at the center. It is also relevant that Farr discusses Church’s visual imagery of Edenic places in relation to Dickinson’s “narrative of Master,” an identity scholars often link with Bowles. We will return to Dickinson's allusions to Church’s South American landscapes in the discussion of “Love thou art high" (F452, J453). Church’s visual metaphors for paradise were an important vehicle for Dickinson’s global imaginary.

Sources

Farr, Judith. The Passion of Emily Dickinson. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 1992, 231-32.

Delight is as the flight –

Or in the Ratio of it,

As the Schools would say –

The Rainbow's way –

A Skein

Flung colored, after Rain,

Would suit as bright,

Except that flight

Were Aliment –

"If it would last"

I asked the East,

When that Bent Stripe

Struck up my childish

Firmament –

And I, for glee,

Took Rainbows, as the common

way,

And empty skies

The Eccentricity –

And so with Lives –

And so with Butterflies –

Seen magic – through the

fright

That they will cheat the sight –

And Dower latitudes far on –

Some sudden morn –

Our portion – in the fashion –

Done –

Link to EDA manuscript. Originally in Poems: Packet XIV, Mixed Fasciles. Includes 33 poems, written in ink, ca. 1860-1862, Houghton Library – (74a). Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. First published in Further Poems (1929), 77, as three stanzas of 9, 10, and 9 lines; in later collections, as three stanzas of 7 lines.

Dickinson copied this poem into Fascicle 13 in the 7th place, in early 1862. This meditation on “delight” measured in the magical terms of the eccentric “Rainbow’s way,” stares into the face of commonality, if not despair. Suzanne Juhasz says:

The ratio that must be measured and understood is the proportion between having and losing, presence and absence. Obviously, if rainbows are the eccentricity, empty skies the common way, this proportion is weighted in favor of pain.

But apparent binaries like “presence and absence” are not clear or simply antithetical in Dickinson’s poetic universe. Let’s focus on the image of “flight,” the exact rhyme with “delight” and a word with many connotations, not least of them the ultimate mobility of birds, bees and butterflies, Dickinson's favorite images of mobility. In the first line, flight seems to refer to both the sudden appearance of the rainbow and is fading and departure. The ratio, or proportion, of delight depends up our ability to balance the presence of beauty against its absence or presence in memory. But even this is not satisfactory, because, the speaker notes, that mere beauty or brightness is not the issue. If it were, the rainbow “flung” like colored skeins of the housewife’s threads or yarns, “would suit.” “Except that flight / Were aliment –”

The Dickinson Lexicon defines aliment as “Food; nourishment; sustenance; life support; essential provisions.” It reminds us of the line in Dickinson’s letter to Bowles, discussed above, in which she compares his presence in her life to the “air” the gills of a fish ask for. This is a complicated image in which Dickinson portrays herself as "a fish out of water." In reality, fish use "gills" to extract "air" or, more precisely, oxygen, from the water in which they swim. She depicts herself as performing a similar or metaphorical extraction of life-sustaining air from the presence, friendship, writing of Bowles. It is an almost metaphysical conceit.

In the next stanza, the speaker compares “Lives” that wish to be all rainbows but have to accept their ephemerality for the commonplace empty skies to “Butterflies,” who seem magical but leave our region to “dower” or enrich “latitudes far on.” Their disappearance leaves us bereft of beauty and the poem ends on a one-word note of finality: “Done.” Still, butterflies travel across oceans and continents in their migrations. They are the original, model global citizens, and they always return in the spring.

Sources

Juhasz, Suzanne. The Undiscovered Continent: Emily Dickinson and the Space of the Mind. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 87-90.

How the old Mountains drip

with Sunset

How the Hemlocks burn –

How the Dun Brake is draped

in Cinder

+By the Wizard Sun –

How the old Steeples hand

the Scarlet

Till the Ball is full –

Have I the lip of the Flamingo

That I dare to tell?

Then, how the Fire ebbs like Billows –

Touching all the Grass

With a departing – Sapphire – feature –

As a Duchess passed –

How a small Dusk crawls

on the Village

Till the Houses blot

And the odd Flambeau, no men

carry

Glimmer on the Street –

How it is Night – in Nest

and Kennel –

And where was the Wood –

+Just a Dome of Abyss is Bowing

+Into Solitude –

These are the +Visions +flitted

Guido –

Titian – never told –

Domenichino dropped his pencil –

+Paralyzed, with Gold

+By the Setting Sun + Acres of Masts are standing

+back of Solitude [for Into: next to – • At the • After – • Unto]

+Fashions – + baffled – +Powerless to unfold –

Link to EDA manuscript. Originally in Poems: Packet XXIII, Fascicle 13 (part). Includes 11 poems, written in ink, dated ca. 1861, Houghton Library – (129a). Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. First published in Poems (1896), 134-35, with alternatives for lines 3, 19 ("nodding"), 21 ("baffled"), and 24 adopted.

Dickinson copied this poem into Fascicle 13 in the 17th or penultimate position. It alternates longer lines of 10 (in the first line) and 9 syllables with lines of 5 syllables, a disruption of the hymn meter. It takes up the image of sunset over the mountains, an emblem of permanence we saw in “Me change! Me alter!” discussed above. This sunset, however, is destructive, ending in a “Night” that blots out “the Wood” and calls forth this amazing line:

Just a Dome of Abyss is Bowing

into Solitude –

Its variant, "Acres of Masts are standing," is also intriguing, imagining the trees of the wood already harvested and turned into masts for sailing ships that will circumnavigate the world.

In the last stanza, Dickinson mentions three Italian painters, Guido Reni (1575-1642), Titian (1488-1576) and Domenichino (1581-1641), all well known to 19th century Americans for their religious and mythological subjects. Titian’s application and use of color was particularly noteworthy, as in this painting, "The Rape of Europa" (c. 1560-1562). and would influence Renaissance as well as modern artists.

Dickinson's speaker acknowledges that all three artists had such “Visions” but could not capture them in painting, just as she wonders:

Have I the lip of the Flamingo / That I dare to tell?

Douglas Leonard argues that in this poem “fascicle 13 culminates its running meditation on the relation between nature and the artist. Here nature’s two great talents–art and murder–are fused; in the end the human artist is slain by beauty.”

Cynthia Wolff offers a long reading of the poem framed by the argument:

If sunrise, properly limned, is the opening volley of God’s assault upon mankind, Dickinson knew that, comprehensively understood, the story of sunset is an abomination. … the transcendent truth inherent in sunset–that the visible world’s most salient feature is its slow disintegration into nothingness–is perhaps not accessible to an artist of gloriously resplendent oil paintings. How is it possible to draw extinction?

The poem questions whether human art, visual or verbal, are capacious or daring enough to represent beauty and nothingness. In its answer to this question, it contradicts an earlier poem, “The Robin’s my Criterion for Tune” (F256, J285), in which the speaker affirms, “I see – New Englandly.” Here, the speaker needs to have “the lip of the Flamingo,” a colorful and exotic bird whose name comes from the Spanish or Portuguese word for "flame-colored," to “tell” what she sees. Does this etymology connect the flamingo speaker with volcanoes, which in "A still Volcano life"(F517, J601), Dickinson linked with the "Torrid – Symbol" and "lips that never lie"? Human and local lips, even the song of the Robin that Dickinson earlier took as “my Criterion for Tune,” will not suffice. While the flamingo betokens tropical climates around the globe, the artists mentioned take us to Renaissance Italy, but even these visionaries are not up to the task.

The poem questions whether human art, visual or verbal, are capacious or daring enough to represent beauty and nothingness. In its answer to this question, it contradicts an earlier poem, “The Robin’s my Criterion for Tune” (F256, J285), in which the speaker affirms, “I see – New Englandly.” Here, the speaker needs to have “the lip of the Flamingo,” a colorful and exotic bird whose name comes from the Spanish or Portuguese word for "flame-colored," to “tell” what she sees. Does this etymology connect the flamingo speaker with volcanoes, which in "A still Volcano life"(F517, J601), Dickinson linked with the "Torrid – Symbol" and "lips that never lie"? Human and local lips, even the song of the Robin that Dickinson earlier took as “my Criterion for Tune,” will not suffice. While the flamingo betokens tropical climates around the globe, the artists mentioned take us to Renaissance Italy, but even these visionaries are not up to the task.

Sources

Leonard, Douglas. “Certain Slants of Light: Exploring the Art of Dickinson’s Fascicle 13.” Approaches to Teaching Dickinson’s Poetry. Eds. Robin Riley Fast and Christine Mack Gordon. New York: Modern Language Association, 1989, 128, 131-33.

Wolff, Cynthia. Emily Dickinson. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co., Inc. 1988, 290-91, 302.

I think the Hemlock likes to stand

Upon a Marge of Snow –

It suits his own Austerity –

And satisfies an awe

That men, must slake in Wilderness –

+And in the Desert – cloy –

An + instinct for the +Hoar, the Bald —

Lapland's –nescessity –

The Hemlock's nature thrives – on cold –

The Gnash of Northern winds

Is sweetest nutriment – to him -

His +best Norwegian Wines

To satin Races – he is nought –

But Children on the Don,

Beneath his Tabernacles, play,

And Dnieper Wrestlers, run.

+or +hunger + drear +good

Link to EDA manuscript. Originally in Poems: Packet XIII, Mixed Fasciles. Includes 27 poems, written in ink, ca. 1862, Houghton Library – (63a). Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. First published in Poems (1890), 104-5, with the alternative for line 6 adopted.

Dickinson copied this poem into Fascicle 20 in the 5th place, around Autumn 1862, and it is a fitting introduction to winter. Its hymn form of common meter and chilly locales suggest, to Jane Eberwein, “how her region’s bleak winter landscapes emblematized Puritan grimness and integrity.” Indeed, a variant for "Hoar," as in frost, is "drear."

Its global imaginary takes us to places antithetical to the tropical landscapes of the previous poem: Lapland, the northernmost region of Finland, Norway, another Scandinavian country whose “wines” mentioned in the poem are more like our American ciders, the Don and Dnieper Rivers that flow through Russia. These places are associated with “austerity,” “an instinct for the Hoar, the Bald … necessity,” but also “awe,” a crucial word in Dickinson’s Lexicon, which means “Reverence; sublimity; veneration; respectful fear.” Indeed, the “Gnash of Northern winds,” a powerful use of diction, “Is sweetest nutriment” to the Hemlock, which “stands” on the “marge of snow,” but also “stands” for a certain, call it, “Yankee” sensibility of grim determination, independence, hardiness, survival.

Sources

Eberwein, Jane. "New England Puritan Heritage." Emily Dickinson in Context. Ed. Eliza Richards. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013, 46-55, 54.

It would have starved a Gnat –

To live so small as I –

And yet, I was a living child –

With Food's nescessity

Opon me – like a Claw –

I could no more remove

Than I could +coax a Leech

away –

Or make a Dragon – move –

Nor like the Gnat – had I –

The privilege to fly

And +seek a Dinner for myself –

How mightier He – than I!

Nor like Himself – the Art

Opon the Window Pane

To gad my little Being out –

And not begin – again –

+ Modify +gain

Link to EDA manuscript. Originally in Poems: Packet XXXIV, Fascicle 21. Includes 17 poems, written in ink, ca. 1862, Houghton Library – (182c). Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. First published in Bolts of Melody (1945), 100, from a transcript of A (a tr362), with the alternative for line 2 adopted.

Dickinson copied this poem into Fascicle 21 in the 5th place in late 1862. It is written in short meter, 6686 syllables, appropriate for a poem about childhood deprivation, living on less than what “would have starved a Gnat,” a very small flying insect that usually congregates in clouds, but here is singular as if under a microscope.

Dickinson copied this poem into Fascicle 21 in the 5th place in late 1862. It is written in short meter, 6686 syllables, appropriate for a poem about childhood deprivation, living on less than what “would have starved a Gnat,” a very small flying insect that usually congregates in clouds, but here is singular as if under a microscope.

Sharon Leiter groups this poem with others that evoke childhood suffering and starvation written during this period: “I was the slightest in the House –” (F473, J486) and “I had been hungry all the Years” (F439, J579), but calls the speaker of this poem “the most diminished and dehumanized.” Some scholars speculate that God, not parents are the source of the speaker’s deprivation, while others, like Cristanne Miller, note the masculinity of the gnat, and speculate that a child’s persona was Dickinson’s strategy for critiquing her diminished position as a woman in a patriarchal society. In the light of these readings, Leiter cautions against confusing “the poetic truth [Dickinson] had to tell about her childhood and the more complex reality of her early years.

What seems striking, in terms of our theme of global consciousness, is the Gnat’s “privilege to fly / And seek a Dinner” for himself. That is the measure of his “might,” his independence and, especially, his mobility. In a poem discussed earlier, we saw that "flight” was linked to "delight." Nor, continues the diminished speaker, does she have

like Himself – the Art

Opon the Window Pane

to gad my little Being out –

Leiter interprets these lines as the speaker’s inability to commit suicide and thus “not begin – again” the next day with the same dreadful starvation. According to the Lexicon, however, Dickinson used "gad" to mean “Coax; remove; steal; pry.” Webster’s defines it as “To walk about; to rove or ramble idly or without any fixed purpose,” and gives as an illustration a line from the Hebrew Bible's Book of Ecclesiastes with a gendered warning:

Give the water no passage, neither a wicked woman liberty to gad about.

The example from Milton, by contrasts, offers “gadding vines” in Eden, rambling in growth.

Is it possible that what could save, nourish, and sustain this speaker is the ability not only to fly and catch her dinner but “the Art,” as she calls it, to imaginatively rove and ramble around the world of possibilities in order to grow?

Sources

Leiter, Sharon. Critical Companion to Emily Dickinson: A Literary Reference to her Life and Work. New York: Facts on File, 2007, 131-32.

Miller, Cristanne. Emily Dickinson: A Poet’s Grammar. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1987, 98-104.

Love – thou art high –

I cannot climb thee –

But, were it Two –

Who knows but we –

Taking turns – at the Chim –

borazo –

Ducal – at last – stand

up by thee –

Love – thou art deep –

I cannot cross thee –

But, were there Two

Instead of One –

Rower, and Yacht – some

sovreign Summer –

Who knows – but we'd reach

the Sun?

Love – thou art Vailed –

A few – behold thee –

Smile – and alter – and

prattle – and die –

Bliss – were an Oddity -

without thee –

Nicknamed by God –

Eternity –

Link to EDA manuscript. Originally in Poems: Packet XXXIV, Fascicle 21. Includes 17 poems, written in ink, ca. 1862, Houghton Library – (184d-185). Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. First published in London Mercury, 19 (February 1929), 355; Further Poems (1929), 145, as three stanzas of 7, 8, and 8 lines.

Dickinson copied this poem into Fascicle 21 in the 14th position sometime late in 1862. Its form is unusual, all long lines without the alteration of shorter lines as in the hymn meter. Perhaps because it imagines or aspires to a love of “two,” of equals. Its three stanzas each take up a variation on the same theme: “Love – thou art …,” a definitional form Dickinson used frequently.

Noteworthy is Dickinson’s representation of Love in the spatial terms of a landscape: a high mountain that must be climbed, a deep lake that must be rowed across, a view or scene or face that is veiled by clouds or mist. Several words link this poem to “Me change! Me alter!” discussed earlier, especially naming the high mountain “Chimborazo,” an active volcano in the Cordillera range of the Andes, depicted in several of Frederic Church’s popular paintings exhibited in the 1850s.

Judith Farr explores this allusion, arguing that “The volcano is [Dickinson’s] symbol for passion suppressed, not only love but rage. Her choice of it was apt (particularly in the case of Chimborazo, an active volcano ringed by ice),” and also showed her familiarity with Church’s monumental painting that romanticized this volcano and its Edenic landscape, “The Heart of the Andes” (1859). Ten feet long and “not a mere a painting but a national event,” it was displayed in New York in April 1859 to rapturous crowds and lauded in the Springfield Republican.

Farr notes that the painting inspired a pamphlet by Theodore Winthrop, the subject of an article in the Atlantic Monthly in August 1861, which Dickinson would have seen. Winthrop extolled Chimborazo in terms that would have piqued and challenged Dickinson’s imagination:

this miracle of vastness, and peace, and beauty, not merely white snow against blue sky, but light against heaven. No poetry of words can fitly paint its symmetry, its stateliness, the power of its crown, up into the empyrean. The poetry is before our eyes … It gives a vision of glory, and every one who beholds it is a poet.

Farr also mentions another Church painting, “Chimborazo,” which, she argues, resembles the elements of Dickinson’s poem: “the mountain peak towering nearly into invisibility and a single rower, trying to cross water toward it, as someone watches him in the summer sunlight.” Although this painting was not finished until 1864, well after Dickinson composed her poem, Farr suspects Dickinson could have heard of the painting or sketches for it described to her by Bowles.

One last frame for this poem is from Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Aurora Leigh, a poem Dickinson and Bowles both adored. The heroine wonders

by how many feet / Mount Chimborazo outsoars Himmeleh” (Bk 1. line 14)

Dickinson also alludes to “Himmeleh,” another important global reference, in several poems, often about love and scale.

Sources

Farr, Judith. The Passion of Emily Dickinson. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 1992, 212, 233-36.

The World – feels Dusty

When We stop to Die –

We want the Dew – then –

Honors – taste dry –

Flags – vex a Dying face –

But the least Fan

Stirred by a friend's Hand –

Cools – like the Rain –

Mine be the Ministry

When thy Thirst comes –

Dews of Thessaly, to fetch –

And Hybla Balms –

Link to EDA manuscript. Originally in Poems: Packet XXXI, Fascicle 23. Includes 20 poems, written in ink, ca, Houghton Library – (168c). 1862. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. First published in Atlantic Monthly, 143 (February 1929), 186; Further Poems (1929), 109.

Dickinson copied this poem into Fascicle 23 in the 13th place in late 1862. It is written in short lines of 5 or 4 syllables and loose rhymes. It is one of the twelve songs Aaron Copland set to music. To Listen to Rebekah Schweitzer's rendition of the song, visit the White Heat Youtube Channel.

Although Dickinson wrote several poems imagining the death of a beloved man, this one is about death on the battlefield and, thus, appropriate for the autumn of 1862, which was a season of bloody battles during the Civil War. Here, though, the “Honors” of war “taste dry,” and “Flags – vex a Dying face.” There is no glory or heroics, Dickinson implies, when dying in this war.

What soothes the dying is the ministrations of a friend, who stirs a “Fan” to cool a feverish face. The antidote to feeling “dusty,” a word that suggests human frailty and divine carelessness, is “Dew.” Dew, of course, suggests morning and, thus, rebirth and revival. In another poem of this period, Dickinson links “the news of Dews” heard by thirsty flowers with the “gospel” or good news of heaven (“Like Flowers, that heard the news of Dews” [F361]).

In this poem, she links the ministrations of friendship with two faraway places: the “Dews of Thessaly” and “Hybla Balms.” Susan Kornfeld notes:

Hybla is a town in Sicily famed since antiquity for its bees and honey. Romantic author Leigh Hunt's 1883 booklet, "A Jar of Honey from Mount Hybla," draws from myth and Greek poet Theocritus in discussing the restorative properties of this honey.

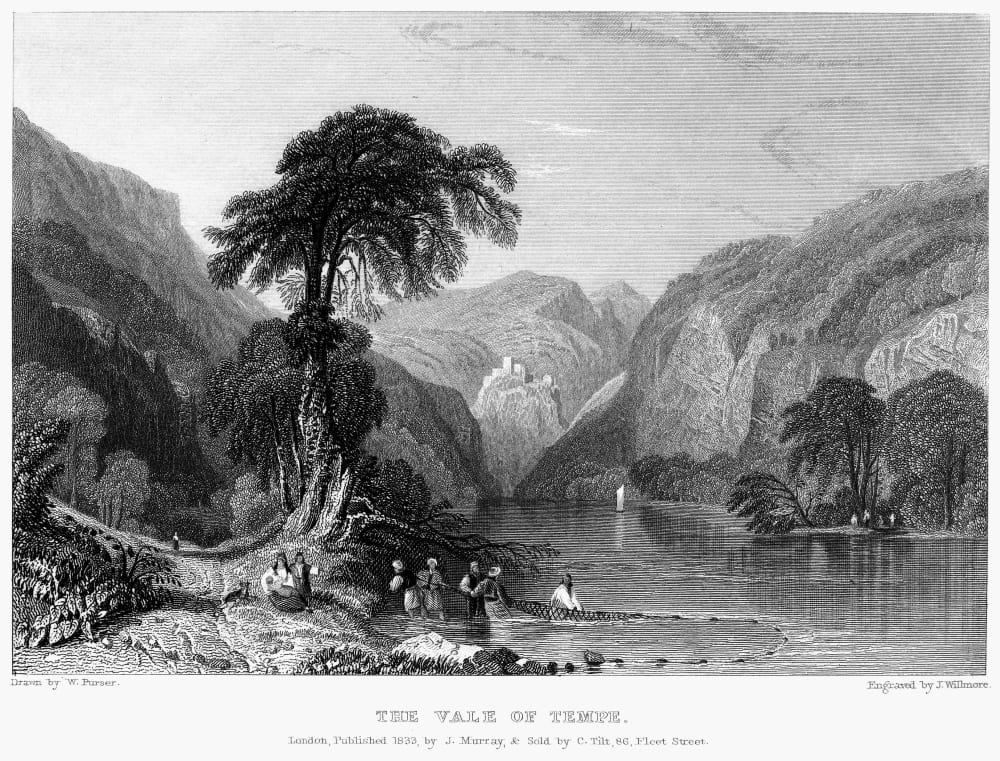

The "Dews of Thessaly" are probably a reference to the lovely pools and waters of the Vale of Tempe – located in the north of Thessaly (a region of modern Greece). John Lemprière in his Classical Dictionary gives this description of Tempe:

“… The poets have described it as the most delightful spot on the earth, with continual cooling shades, and verdant walks, which the warbling of birds rendered more pleasant and romantic, and which the gods often honored with their presence.”

How far from the killing fields of Maryland and Virginia and the exclusive heaven of Christianity!

Sources

Kornfeld, Susan. “The World – feels Dusty.” The prowling bee. 26 August 2013.

Of Brussels – it was not –

Of Kidderminster? Nay –

The Winds did buy it of

the Woods –

They – sold it unto me

It was a gentle price –

The poorest – could afford –

It was within the frugal

purse

Of Beggar – or of Bird –

Of small and spicy + Yards –

In hue – a mellow Dun –

Of Sunshine – and of Sere -

Composed –

But, principally – of Sun –

The Wind – unrolled it fast –

And spread it on the Ground –

Upholsterer +of the Pines – is

He –

Upholsterer – of the Pond –

+Breadths – +Of the Sea • of the land

Link to EDA manuscript. Originally in Poems: Loose sheets. Various poems. MS Am 1118.3 (383), Houghton Library – (383a). Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. First published in Bolts of Melody (1945), 331, from a transcript of B (a tr54, 54a).

Dickinson copied this poem into Fascicle 24 in the 5th place. Last week, we looked extensively at poems in this Fascicle and their relation to the Civil War, especially the Battle of Antietam that occurred on September 17, 1862. Franklin notes that Dickinson sent a fair copy to Louise and Frances Norcross, “perhaps in early 1863” and that according to a note by Frances “the poem had been sent ‘with a pine needle.’”

This lovely detail helps with the riddle of the poem that begins by describing what “it” was not: beautiful carpets made in Brussels, which innovated the machined uncut loop pile, and in Kidderminster, England, the center of British carpet manufacturing in the 18th and 19th centuries. While showing her familiarity with these luxuries and the places of their production, Dickinson rejects them for something less cultured but far more precious, produced by the “Wind,” whom she describes unforgettably as “Upholsterer of the Pines” and “Upholsterer – of the Pond.”

In reading through Samuel Bowles’ letter printed in the Springfield Republican this week describing his travels in Switzerland (excerpted in the Biography section of the post), we came across the following passage, which seems like a possible inspiration for Dickinson’s poem. First, he quotes a verse from “Mrs. Browning,” a writer whom they both adored, from her utopian poem, “An Island” (1837), to describe a scene that moves him immensely:

Hills running up to heaven for light,

Through woods that half way ran;

As if to mock in their wild delight

The wilder heart of man;

Only they are greener and gladder far

Than human hearts every are.

Bowles continues, though is a very different mood:

Yet one of these hillsides, when in shadow, symbolizes and sympathizes with, as no other natural scenery I ever beheld, the deep unutterable pathos of humanity. It looks out upon you like a great human soul in imperishable and unspeakable sorrow. These woods, too, are the paradise of mosses and ferns. The amateur in these should make a special pilgrimage to the Black Forest. The mosses, thick, soft and of every hue of green, shaded with yellow and red, are not content to cover the ground with a carpet that no tapestry can rival, but often mount the trees themselves and clothe the trunks and branches with their fascinating resurrection life.

Dickinson swaps the pine needles of Amherst's woods for his mosses of the Black Forest, but the poignant feeling is the same. She may not have traveled to Switzerland, but Bowles was her conduit, her eyes and ears to a wider world that allowed the poet to expand her imagination to places she would never physically know.

Sources

Hsu, Li-Hsin. Emily Dickinson’s Poetic Mapping of the World. School of Literature, Languages and Cultures: University of Edinburgh, 2012. PhD dissertation, 319.