On Choosing the Poems: A Musician’s Approach

Dr. Nicole Panizza, University of Coventry

As a direct result of her musical training, Emily Dickinson was able to effectively harness the three basic principles of musical construction: melody, harmony, and rhythm, and then carefully tailor them to her own individual style and literary voice. A master of economy with her use of concise and direct forms, she then combined these with her choice of a slow, short meter. This enabled Dickinson to bring each syllable into close-up, as if using a microscope. There is a deep and steady focus of thought and image, her words connecting yet somehow standing in independence from each other. Dickinson presents her ideas and thoughts as mosaics: gem-like miniatures that paradoxically open up perspectives on a very grand scale. For the musician engaging with her work, these fundamental musical building blocks provide a welcome synchronicity: a safe anchor from which to analyze her work.

As a direct result of her musical training, Emily Dickinson was able to effectively harness the three basic principles of musical construction: melody, harmony, and rhythm, and then carefully tailor them to her own individual style and literary voice. A master of economy with her use of concise and direct forms, she then combined these with her choice of a slow, short meter. This enabled Dickinson to bring each syllable into close-up, as if using a microscope. There is a deep and steady focus of thought and image, her words connecting yet somehow standing in independence from each other. Dickinson presents her ideas and thoughts as mosaics: gem-like miniatures that paradoxically open up perspectives on a very grand scale. For the musician engaging with her work, these fundamental musical building blocks provide a welcome synchronicity: a safe anchor from which to analyze her work.

The importance of melody in Dickinson’s literary approach cannot be overlooked, especially within the discussion of her inherent musicality. Melody features regularly in Dickinson’s poems and letters, sometimes in direct reference to musical idioms, although more often as a pertinent metaphor for relationships. These relationships were either personal (i.e. friendships, familial unions, romantic interests) or pertaining to the relationship between nature and religion, particularly immortality. Dickinson herself described the time spent with friends as “those melodious moments of which friends are composed” (L969, 1885). On the event of Judge Otis Lord’s death, a love interest that has been well documented, she observed, “Abstinence from Melody was what made him die” (L968-1885).

In her 1862 poem “I would not paint – a picture – ” (F348A, J505), Dickinson refers to the arts but as an observer of poetry, painting, and music. For music, she says: “I would not talk, like Cornets —,” a soft, more muted alternative to the trumpet or bugle, and often used as a metaphor for foreboding and danger, as in her poem “There came a Wind like a Bugle” (F1618, J1593). Rather than “talking,” or making music, she prefers to be “Raised softly to the Ceilings … By but a lip of Metal — The pier to my Pontoon —”. Here, Dickinson describes a spiritual journey with music as the vehicle: her soul (pontoon) being released via the pier (music). In the final lines of this poem, Dickinson wonders what the effect would be,

Had I the art to stun myself

with Bolts of Melody!

This image offers both reader and musician an insight into Dickinson’s personal relationship to melody and musical phraseology, indicating her apprehension of its sheer electric force, and serving as a metaphor for Dickinson’s literary discourse.

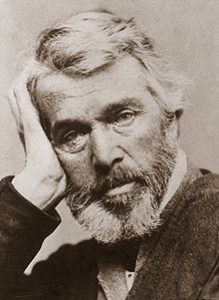

In addition to Dickinson’s references to melody, harmony played an equally compelling and integral role in her creative approach, although it represented something very different. In the poem “‘Nature’ is what we see” (F721, J668), the speaker affirms that “Nature is Harmony,” indicating the extent to which she felt and experienced the cooperation and kinship of nature as musical. Indeed, Emily Dickinson echoed the writer Thomas Carlyle (whom she held in high regard) in his musings regarding the interconnectedness of poetry, music and nature.

Musicians wrestle everywhere (F229B, J157)

Musicians wrestle everywhere –

All day – among the crowded air

I hear the silver strife –

And – waking – long before the morn –

Such transport breaks opon the town

I think it that “New life”!

It is not Bird – it has no nest –

Nor “Band” – in brass and scarlet -

drest –

Nor Tamborin – nor Man –

It is not Hymn from pulpit read –

The “Morning Stars” the Treble led

On Time's first afternoon!

Some – say – it is “the Spheres” – at play!

Some say – that bright Majority

Of vanished Dames – and Men!

Some – think it service in the place

Where we – with late – celestial face –

Please God – shall ascertain!

EDA manuscript: Originally in Poems: Packet XV, Fascicle 9, Houghton Library – (82a). Includes 29 poems, written in ink, ca. 1862. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. First published in Poems (1891), 84, from the fascicle (B).

This poem, first sent to Susan Dickinson in late spring 1861 and then copied into Fascicle 9, not only makes full use of direct musical terminology and reference (“band,” “hymn,” “tamborin”) but also explores the phenomenon of the poet as celestial muse, with the ability to attune to a music beyond the everyday noises within her domestic and community environs, as described in stanza one.

At the end of the second stanza, Dickinson posits that music may be the song of the “Morning Stars” on the first afternoon of creation, a direct reference of the Book of Job where God asks

Where was thou when I laid the foundations of the earth … when the morning stars sang together, and all the Sons of God shouted for joy?”(Job 38: 4-7).

Further, the hymn form of these verses, as written by J. Montgomery in 1849, may have inspired Dickinson, particularly in reference to the “the Treble” as a soprano, or other high voice:

The morning stars in concert sang

When God created heaven and earth

And earth and heaven with music sang

When angels hail’d Messiah’s birth.

In the third stanza, Dickinson’s reference to Music, or Harmony of the Spheres (“Some – say — it is ‘the Spheres’ – at play”), directly resonates with a theorem of Pythagoras (570-495 BC): if heavenly bodies moved according to mathematical symmetry and equation, and if music could equally be viewed as a mathematical construct, then each celestial body had its own set of tones or notes – a harmonic embodiment of a spiritual symphony. Indeed, Dickinson defines musical “transport” as the moment when she wakes to the sound of saints singing in full chorus, and refers to a (church) service that provides an individual spiritual path:

Of vanished Dames — and Men!

Some — think it service in the place

Where we — with late — celestial face —

Sharon Leiter addresses the role of punctuation in Dickinson’s verse, particularly as a means of musical device. She synthesizes the work of several scholars who position Dickinson’s use of the dash as a direct mechanism for both musical tension and reflection. Between 1860 and 1863 Dickinson adopted a frenetic, almost obsessive use of the dash – so much so that it arguably superseded her use of almost every other punctuation marking. Scholars suggest that this may have been due to increasing (and unrelenting) personal stress, creating a jarring and unsettling effect for the reader.

However, when approaching this device from an aural/musical perspective, the musician is offered an opportunity to experience Dickinson as both composer and performer. As Kamilla Denman notes in her essay, “Emily Dickinson’s Volcanic Punctuation,” Dickinson’s use of punctuation

expands the space and pitch in which words are uttered, underlines or undercuts words, blends words, or dislocates them from their context.

Denman further observes:

Dickinson’s punctuation affirms the silent and the non-verbal, the spaces between the words that lend resonance and emphasis to poetry. In the punctuation of her poetry, Dickinson creates a haunting, subversive, impelling harmony of language, wordless sound (emotional tonality and musical rhythms), and silence. Like songs set to music, Dickinson’s poems are accompanied by a punctuation of various pauses, tone, and rhythms that extend, modify, and emancipate her words, while pointing to the silent places from which language erupts.

Sources

Denman, Kamilla. “Emily Dickinson’s Volcanic Punctuation.” Emily Dickinson: A Collection of Critical Essays. Ed. Judith Farr. New York: Prentice Hall, 1996, 187-205, 198-199.

Leiter, Sharon. “Punctuation.” Critical Companion to Emily Dickinson: A Literary Reference to her Life and Work. New York: Facts on File, 2007, 374-377.

Better – than Music (F378A, J503)

Better – than Music!

For I – who heard it –

I was used – to the Birds -

before –

This – was different – 'Twas

Translation –

Of all tunes I knew -

and more –

'Twas'nt contained – like other

stanza –

No one could play it – the

second time –

But the Composer – perfect

Mozart –

Perish with him – that

keyless Rhyme!

Children – so +told how Brooks

in Eden –

Bubbled a better – melody –

Quaintly infer – Eve's great

surrender –

Urging the feet – that would -

not – fly –

Children – +matured – are wiser -

mostly –

Eden – a legend – dimly +told –

Eve – and the Anguish -

Grandame's story –

But – I was telling a

tune – I heard –

Not such a strain – the

Church – baptizes –

When the last Saint -

goes up the Aisles –

Not such a stanza

splits the silence –

When the Redemption +strikes her Bells –

Let me not + spill – it's

smallest cadence –

Humming – for promise – when

alone –

Humming – until my faint

Rehearsal –

Drop into tune – around the

Throne –

+assured that + grown up

+learned • crooned + shakes

+lose • waste

EDA manuscript: Originally in Poems: Packet VI, Fascicle 18, Houghton Library – (27). Includes 13 poems, written in ink, dated ca. 1862. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. First published in Bolts of Melody (1945), 235, from a transcript of A (a tr285), as six quatrains, without the transposition, with the alternatives for lines 10 and 22 ("lose") adopted and the alternative for line 21 ("shakes") used in line 20.

A fitting example that resonates with the poem, “Of all the Sounds dispatched abroad” (F334, J321), also written in 1862, Dickinson’s poem “Better — than Music!” explores the role of poet as translator – the act of transforming a musical epiphany into language. As Robin Riley Fast observes, Dickinson

recalls a transcendent music which is both evanescent and hers (“Let me not spill – its smallest cadence”), which both connects her to Eve (and the tempting music she might have heard) and assures her own access to heaven.

The opening stanza aptly describes a “music” which she has never heard: one that is more than the birds and sounds of nature. Dickinson’s use of the dash creates a superstructure of awe, wonderment and musical suspension–emulating a lyric, song-like rendering of her experience in real time. In the second stanza, she continues this theme by reinforcing the lack of structure, circumference and boundary, and a lack of identity and compass (“Keyless Rhyme!”). Dickinson posits the notion that this “playing” was unique and not to be repeated—the composer was a “perfect Mozart” (a reference to her knowledge of Western classical music tradition), and the music would “Perish with him.”

The final stanza sees the speaker in the act of prayer: she has received a private and precious gift that she prizes, holds dear, and will guard against anyone else hearing. She offers the value of musical rest, category, and punctuation, as in a “smallest cadence” which must not be spilled into the common air. She alerts the reader to her intention of lyrically recreating this “music,” in private and alone, until such time as she dies. Her “Humming,” her “faint Rehearsal,” will “Drop into tune” and the music will take on its true meaning and purpose.

Sources

Fast, Robin Riley. “Workshop Two: Poem 315, ‘He Fumbles at your Soul.’” Emily Dickinson: A Celebration for Readers. Eds. Suzanne Juhasz and Cristanne Miller. New York: Routledge, 1989, 55-60, 56.

Put up my lute! (F324A, J261)

Put up my lute!

What of – my Music!

Since the sole ear I

cared to charm –

Passive – as Granite – laps

my music –

Sobbing – will suit – as well

as psalm!

Would but the “Memnon” of the Desert –

Teach me the strain

That vanquished Him –

When He – surrendered

to the Sunrise –

Maybe – that – would

awaken – them!

EDA manuscript: Originally in Poems: Packet XXIII, Fascicle 13 (part), Houghton Library – (127d). Includes 11 poems, written in ink, dated ca. 1861. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. First published in Unpublished Poems (1935), 140, as two quatrains.

In her 1988 book, Emily Dickinson: Personae and Performance, Elizabeth Phillips invites the reader to consider the connection between Dickinson's “Put up my lute!” and Robert Browning’s “One Way of Love,” from Men and Women (1855), as a key inspiration and informant. Browning writes:

How many a month I strove to suit

These stubborn fingers to the lute!

Today I venture all I know

She will not hear my music so?

Another influence is Shakespeare’s use of and reference to the lute (namely, in Richard III and Henry IV), as a symbol of the power of music, and as a metaphor for love, lust, beauty and flirtation. Dickinson resonated with the common belief that this instrument could transport the listener into a form of ecstasy and offered a viable form of spiritual and musical healing. In the first stanza of the poem, Dickinson discards the lute (“Put up my lute!”) as a reference to shedding a perceived “non-emotional response” to her poetic process and output, possibly by peers (“What of — my Music!”). The longing for a wider audience, and her frustration at the fact that despite the mood being tragic and heartfelt (“sobbing”), or hymnal and religious (“psalm”), the response is the same.

The second stanza makes reference to Memnon, the Ethiopian warrior king and son of Eon, the dawn goddess. He brought an army to Troy and personally fought against Achilles, who killed him, after which Zeus granted him immortality. One of the great Colossi of Memnon was damaged in the 27 BC earthquake; after which its remaining lower half continued to be heard singing at sunrise. Dickinson makes reference to this well-known myth, and in particular, the shattered statue: conflating the earthquake “strain/That vanquished Him” with the sunrise song that he is said to have sung every day.

Sources

Phillips, Elizabeth. Emily Dickinson: Personae and Performance. Penn State Press, 1988, 126.

He fumbles at your Soul (F477A, J315)

He fumbles at your Soul

As Players at the Keys –

Before they drop full Music

on –

He stuns you by Degrees –

Prepares your brittle substance

For the etherial Blow

By fainter Hammers -

further heard –

Then nearer – Then so – slow –

Your Breath – has +chance

to straighten –

Your Brain – to bubble cool –

Deals One – imperial Thunder –

bolt –

That +peels your naked soul –

When Winds hold Forests in their Paws –

+The Firmaments – are still

+ time +scalps +The Universe – is still

EDA manuscript: Originally in Poems: Packet XIX, Fascicle 22, Houghton Library – (108c). Includes 23 poems, written in ink, dated ca. 1862. Courtesy of Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. First published in Poems (1896), 86, from the fascicle (B), with the alternatives for lines 9 and 12 adopted and the final two lines omitted.

As a profound and compelling example of Dickinson’s use of music reference as a vivid metaphor for male power and oppression, this poem provides a striking and cataclysmic illustration of a slow and seductive succumbing to an all-powerful, charismatic figure. In the first stanza, Dickinson creates an image of a pianist improvising over a few notes, a veritable “warming up” before the full performance begins (“Before they drop full Music on”). The musician, potentially God, or a significant male figure, toys with the writer’s soul, the very essence of their private emotional world. The warm-up provocatively disrupts the listener’s desire to be at one with the intended “full” performance, followed by a slow tease of the “fainter Hammers” – a systematic premonition that all is not well.

Bind me – I still can sing! (F1005, J1005)

Bind me – I still

can sing –

Banish – my mandolin

Strikes true, within –

Slay – and my Soul

shall rise

Chanting to Paradise –

Still thine –

EDA manuscript: Originally in Amherst Manuscript #set 90, Amherst Manuscript #set 90 – Crumbling is not an instant's act – asc:17286 – p. 6. Courtesy of Amherst College, Amherst, MA. First published in Bolts of Melody (1945), 148.

At first glance, this short poem affirms the persistence of music making beyond the obstacles of binding the singer, banishing their instrument, and in the final stanza, slaying them. Dickinson’s choice of words, however, offers several ways of understanding this delirious and enduring power of song, allowing the poem to work on several levels simultaneously.

We might consider who the speaker is addressing in the poem, and almost daring to muzzle her: a divine power, a set of human and material circumstances, a lover who forbids communication and expression? The instrument, a mandolin, is in the lute family and, thus, partakes of the symbolism discussed in relation to “Put up my lute!”—love, lust, as well as ecstasy and healing. Except here, it is being forcibly removed from the player’s hands. Still, even without a player, the poem insists, the mandolin will “strike true – within,” that is, will sound a right and pure note within the mind or soul; implying that this kind of music does not need to be heard.

Even death is no bar to this music and musician, who asserts they will rise up to Paradise chanting this music of the soul. In using the word “slay” for kill, Dickinson retains an echo of its original meaning, described in Dickinson’s Webster's, as “strike with a sword,” which reinforces the connection of this kind of death to the music making of striking the strings.

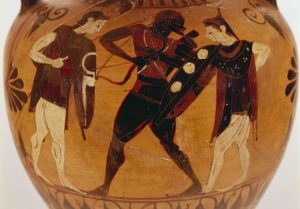

Finally, we might consider this poem to be spoken by Orpheus, the master-musician of ancient mythology, whose music was so powerful, it charmed all living things and even stones. In one story, Orpheus almost succeeds in bringing his wife, Eurydice, back from the underworld by charming Hades, its ruler, with his music. Orpheus fails when he looks back to make sure Eurydice is following him, thus breaking his agreement with Hades. Despondent, he refuses to play and casts aside his lute, or, in other versions, spurns the love of women, and for this he is “slain” by the Maenads, female worshipers of Dionysus. Because the sticks and stones they throw at him refuse to hurt him, the Maenads tear him to pieces. For the Greeks, Orpheus was also a prophet and founder of the “Orphic” mysteries—a powerful male musical/poetic voice for Dickinson to ventriloquize.