On Choosing the Poems

In choosing poems that speak to and illustrate Dickinson’s engagement with Eastern thought, we have been guided by scholars working in this area, some of whom are mentioned in the Sources for this week’s post. Readers also might want to consult volume 22.2 of The Emily Dickinson Journal for 2013, which focuses on new scholarship exploring Dickinson’s engagement with Eastern aesthetic, philosophical, and spiritual values.

Yanbin Kang, who has an essay in this volume, explores many ideas from Chinese thought that appear in Dickinson’s poems as both themes and aesthetic strategies. We have chosen poems that illustrate a range of them. Some of these themes include: living in the present, letting go, nurturing the still or “bland” mind, steadfastness and tranquility, achieving a meditation-like repose, the “great death” of the individual and acquisitive ego. Many of these poems make use of a natural setting, since, as Kang notes,

Communion with nature enables the observer to efface the ego and forget the self.

Kang also discusses Dickinson’s language theory, which resembles Daoist thought in preferring silence over speech, and other formal strategies, such as deleting connectives to compress thought and enable ambiguity and simultaneity, suppressing the first person pronoun which suppresses the editorial ego, and the “erasing-while-writing” model of poetry that demonstrates a form of Daoist non-interference. Kang concludes:

This constructed self-awareness of her humility in her speakers is critical to Dickinson’s poetic method.

Sources:

Kang, Yanbin. “Dickinson’s ‘Power to die’ from a Transcultural Perspective.” The Emily Dickinson Journal, 22, 2 (2013): 65-85, 67, 76.

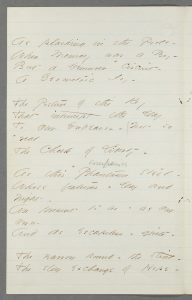

One life of so much consequence – (F248A, J270)

One life of so much

consequence!

Yet I – for it – would pay -

My soul's entire income -

In ceaseless – salary -

One Pearl – +to me – so signal -

That I would instant dive -

Although – I knew - to take it -

Would cost me - just a life!

The Sea is full – I know it!

That – does not blur my Gem!

It burns – distinct from all

the row -

Intact - in Diadem!

The life is thick – I know it!

Yet – not so dense a crowd -

But Monarchs - are perceptible -

Far down the dustiest Road!

+of such proportion

EDA manuscript: "Originally in Poems: Packet XXXVII, fascicle 10. Includes 22 poems, written in ink, ca. 1860-1861. Houghton Library – (203a) Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. First published in New York Herald Tribune Books (10 March 1929), 4, and Further Poems (1929), 142, without stanza division."

Franklin dates this poem to the second half of 1861. We include it in order to discuss the image of the “pearl,” which occurs in other poems around this time, in particular, “Your Riches taught me Poverty” (F418, J 299) and “The Malay took the pearl” (F451A, J452). Many readers understand the pearl as an image of Susan Dickinson: in the first poem mentioned above, as a “treasure” that slipped out of Dickinson’s grasp; and in the second, as the object of desire in an affective struggle between Dickinson and her brother Austin.

Likewise, romance is one of the lenses readers use to understand this poem, but it is layered with poetic ambition. Richard Sewall considers this poem “the climax” of a narrative he constructs around Dickinson’s relationship with Samuel Bowles, the editor of the Springfield Republican, which involves deep feelings, creative striving, rejection, and independence. Combining allusions to the religious and the secular, the poem, he says:

seems to reflect her realization of the price of her commitment to her vocation. The “pearl,” the “gem,” the “diadem,” though never without their religious resonance for her, are by now well-established metaphors for her poetry. She is saying here that the price is worth it. It is tempting to see the last stanza as her ironic comment on the lady poets whose verses graced the columns of the Republican and as her prediction of the ultimate verdict of time.

By contrast to these readings, we can think about Dickinson’s allusion to pearls in the context of Chinese thought. Yanbin Kang, for example, considers the “Malay” who takes the pearl from the acquisitive “Earl” as Dickinson’s embodiment of “Daoist modesty and fearlessness.” To contextualize this reading, Kang cites Han-shan, a Buddhist poet, who wrote:

a pearl fits in a burlap sack

Buddhahood rests under a thatch.

The larger context for Daoist ideas are the parables of Zhuangzi (Chuang Tzu, 369-286 BCE), considered the co-founder, with Laozi, of Daoism, but also regarded as more anarchic and less homocentric than Laozi. On the power of simplicity, Zhuangzi

uses the example of drunken men surviving accidents without fatal damage to illustrate obliviousness to fear and death as a path toward transcendence.

In a famous parable, Zhuangzi remarks that it is

“Ignorance or No-mind,” not “Knowledge, Acumen, or Eloquence,” that retrieves the lost pearl.

This context substantially changes how we might read “One life so so much consequence!”

Sources

Kang, Yanbin. “Dickinson’s ‘Power to die’ from a Transcultural Perspective.” The Emily Dickinson Journal, 22, 2 (2013): 65-85, 72.

Sewall, Richard. The Life of Emily Dickinson. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1980, 506.

A burdock clawed my gown (F289A, J229)

A Burdock -

A Burdock -

clawed my Gown -

Not Burdock's - blame -

But mine -

Who went too near

The Burdock's Den -

A Bog - affronts my shoe -

What else have Bogs - to do -

The only trade they know -

The splashing Men!

Ah, pity – then!

'Tis Minnows can despise!

The Elephant's - calm eyes

Look further on!

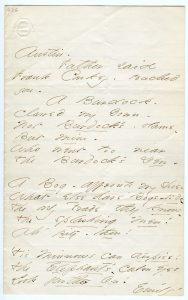

EDA manuscript: "Originally in Amherst Manuscript # 626, letter to Austin Dickinson (L240). Courtesy of Amherst College, Amherst, MA. First published in Bolts of Melody (1945), 73, from the set (B), with the first stanza as a quatrain and with the alternative not adopted."

Dickinson enclosed this poem in a letter to her brother Austin, “about 1861,” according to Thomas Johnson, and introduced it with the comment, “Father said Frank Conkey – touched you–” (L240). Johnson’s note explains:

There was keen political rivalry between Edward Dickinson, a “straight” Whig, and Ithamar Francis Conkey [1788-1870], a “republican” Whig. ED evidently thought that Austin has been “touched” by Conkey’s political thinking.

Johnson refers to tensions within the Whig party over the expansion of slavery. On account of their association with the New England textile industry, the “straight” Whigs de-emphasized the slavery issue, which put them on the same side as the pro-South “Cotton” Whigs, who eventually left to join the Democratic party. The “republican” Whigs, also called “Conscience” Whigs, were based in the Northern states, and split from the Whig party in 1848, when it nominated the slave-owning General Zachary Taylor for president. The Compromise of 1850 brought them back into the fold, but several of their leaders helped found the Republican party, which many joined when the Whig party disappeared.

Yanbin Kang argues that this poem

illustrates the workings of a bland state of mind: an unmentioned harasser is belittled by likening him or her to a “Burdock,” a “Bog,” and finally to “Minnows.” Remaining unaffected by these affronts, the speaker promotes a serene and unperturbed attitude

epitomized by “the Elephant’s – calm eyes” looking out and beyond “The splashing Men.”

It’s important to note that while “blandness” has negative connotations to the Western mind, it was highly valued by Chinese philosophers as an indication of “non-desire, non-contention, non-ego, and non-action,” or what Kang calls “negative wisdom celebrated in some of [Dickinson’s] poems,” which echo the teachings of Dao.

We found no other scholarly commentary on this poem, but did find this poetic appreciation from a poet in Australia:

A BURDOCK-CLAWED MY GOWN

Emily Polites*

05.10.15 7:30 am

(after Emily Dickinson’s poem by the same name)

What’s a girl to do

If a burr invades her shoe?

She’s the one to blame

For the path by which she came

There’s no use for stress

If some mud should spoil her dress

Puddles can’t be asked

To step aside and let her past

Without an ear to hear them, curses are just sounds

Best put by to spend upon the guy who keeps the grounds.

*Emily Polites has achieved a smattering of publications, including Best Australian Poems 2012. Her performance poetry has appeared on TV, radio and online, and she won the audience choice award and runner-up in Melbourne Poetry Idol 2010. Emily and her identical twin Bronwen can be found regularly and joyously listening and performing around Melbourne’s lively spoken word scene.

Sources

Dickinson, Emily. The Letters of Emily Dickinson. Eds. Thomas Johnson and Theodora Ward. 3 vols. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1958, 381.

Kang, Yanbin. “Dickinson’s ‘Power to die’ from a Transcultural Perspective.” The Emily Dickinson Journal, 22, 2 (2013): 65-85, 65, 67.

When we stand on the top of Things (F343, J242)

When we stand on the

tops of Things -

And like the Trees, look down,

The smoke all cleared away

from it -

And mirrors on the scene -

Just laying light – no soul

will wink

Except it have the flaw -

The Sound ones, like the

Hills – +shall stand -

No lightning, +scares away –

The Perfect, nowhere be

afraid -

They bear their +dauntless

Heads,

Where others, dare not

+go at noon,

Protected by their deeds -

The Stars dare shine

occasionally

Opon a spotted World -

And Suns, go surer, for

their Proof,

As if +an axle, held -

+stand up - +drives walk at noon -

+fearless – • tranquil - +a muscle – held

EDA manuscript: [No image is available.] "Originally in Fascicle 16 (H54, 54a). Courtesy of the Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. First published in Franklin, Variorum, 1998."

Franklin dates this poem, which Dickinson included in Fascicle 16, to “About summer 1862.” We should note that Fascicle 16 begins with the poem “Before I got my eye put out” (F336A, J327), which Dickinson will send to Thomas Higginson in August of this year. Michelle Kohler reads that poem as a critique of Emerson’s transcendental vision, which we know was influenced by Eastern philosophies.

Despite this context, and perhaps because of its hymn meter, John Robinson opines:

The poem is thoroughly Puritan in its division of people on other than earned merit and in its expectation of light which is only hinted at now. Yet it does not issue in ideas of duty and guilt but in security.

However, Yanbin Kang senses Eastern ideas in the imagery:

Dickinson uses hills to illustrate steadfastness and tranquility. … Here she alludes to a certain spiritual height, which, when achieved, allows for clarity and limpidity … Writing that even lightning will not make certain souls “wink,” Dickinson suggests that courageous unconcern comes from a pure mind; the reference to “mirrors” also suggests transparency to a Chinese reader attuned to Daoism. … Dickinson’s writing here coincides with Chinese thought: water and the mirror are common tropes for illustrating the sage’s blandness. Zhuangzi famously celebrates the still mind of the sage, which, like still water, functions as a mirror … the sage’s mind is like a mirror in that it chases nothing, welcomes nothing, responds without storing, and thus remains unaffected by external circumstance.

Sources

Kang, Yanbin. “Dickinson’s ‘Power to die’ from a Transcultural Perspective.” The Emily Dickinson Journal, 22, 2 (2013): 65-85, 67-68.

Kohler, Michelle. “Dickinson’s Embodied Eyeball: Transcendentalism and the Scope of Vision.” Emily Dickinson Journal 13.2 (Fall 2004): 27-57.

Robinson, John. Emily Dickinson: Looking to Canaan. Faber Student Guides. London: Faber, 1986, 43-44.

Heaven is so far of the mind (F413, J 370)

Heaven is so far of the

Mind

That were the Mind dissolved -

The Site – of it – by Architect

Could not again be proved -

'Tis Vast – as our Capacity -

As fair – as our idea -

To Him of adequate

desire

No further 'tis, than Here -

EDA manuscript: "Originally in Poems: Packet XIII, Mixed Fasciles, Houghton Library – (66d). Includes 27 poems, written in ink, ca. 1862. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. First published in Further Poems (1929), 108."

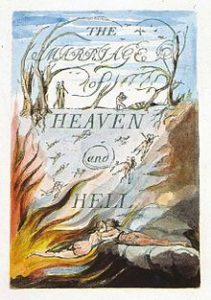

The title page, copy D, held by the Library of Congress

Dickinson included this poem in Fascicle 20, as poem number 18. In her note on “Heaven” as a theme in Dickinson’s work, Rosa Nuckels places the poem’s concept of heaven in a Western mystical tradition of writers like William Blake, who see humanity’s “vast … capacity” to conceive of heaven as well as our propensity to fail at it. Jed Deppman places the poem, and others in Dickinson’s canon, into a Western Enlightenment tradition of

Skeptical Humean questions about the independence of the external world.

By contrast, Yanbin Kang argues that the Buddhist

spiritual ideal [of ] no-mind … is also closely interwoven with [Dickinson’s] idiosyncratic redefinition of heaven, a strategy often eliciting a (mis)-reading as a critique of Christianity.

In this poem, Kang argues,

Dickinson conceives “the Mind dissolved,” specifically the mind of “adequate desire,” as the site of heaven.

For Kang, Dickinson's terms are close to the concept of “no-mind” of Daoism and Chan Buddhism. To illustrate this, Kang refers to the teachings of Hui Neng (638-713), the sixth and final Chan patriarch, who lamented

the human tendency to become “infatuated by sense-objects and to act voluntarily as slaves to their own desires.” … he advocates a life lived free of obstacles … an ideal of self-negation. … In particular, Chan Buddhism uses the trope of ice dissolving in water to illustrate the change from ignorance to enlightenment and suffering to happiness.

Sources

Deppman, Jed. “‘Say Some Philosopher!’” Emily Dickinson in Context. Ed. Eliza Richards. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013, 257-67, 264.

Kang, Yanbin. “Dickinson’s No-body, No-mind, and Non-Action.” ANQ: A Quarterly Journal of Short Articles, Notes, and Reviews 28.2 (2015): 110-17, 110, 112.

Nuckels, Rosa. “Heaven.” An Emily Dickinson Encyclopedia. Ed. Jane Donahue Eberwein. Westport, CT.: Greenwood Press, 1998, 137-38.

A Prison gets to be a friend – (F456, J652)

A Prison gets to be a

friend -

Between it's Ponderous face

And Our's – a Kinsmanship

+express -

And in it's narrow Eyes -

We come to look with

+gratitude

For the appointed Beam

It +deal us – stated as Our

food -

And hungered for – the same -

We learn to know the

Planks -

That answer to Our feet -

So miserable a sound – at first -

Nor even now – so sweet -

As plashing in the Pools -

When Memory was a Boy -

But a Demurer – +Circuit -

A Geometric Joy -

The Posture of the Key

That interrupt the Day

To Our Endeavor – Not so +real

The Cheek of Liberty -

As this +Phantasm steel -

Whose features – Day and

Night -

Are present to us – as Our

Own -

And as escapeless – quite -

The narrow Round – the stint -

The slow exchange of Hope -

For something passiver – Content

Too steep for looking up -

The Liberty we knew

Avoided – +like a Dream -

Too wide for any night

but Heaven -

If + That – indeed – redeem -

+express: exist–•subsist–•arise

+gratitude: fondness–• pleasure

+deal us: furnish

+Circuit: Measure

+real: true–•close–•near

+Phantasm: Companion

+like: As

+That – indeed – redeem -: Even That–redeem

EDA manuscript: "Originally in Poems: Packet XIX, Fascicle 22, Houghton Library – (103a). Includes 23 poems, written in ink, dated ca. 1862. Courtesy of Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. First published in Further Poems (1929), 21-22, as four eight-line stanzas, with alternatives adopted in lines 3 (“exist”) and 21."

Dickinson placed this poem first in Fascicle 22, which might mean that it announces a large set of themes explored in the grouping. It is also related to poems that redefine Heaven such as “Heaven is so far of the mind” which we considered above.

Joanna Yin considers the poem in relation to Dickinson’s circle imagery, which she argues the poet used

to focus the gaze and develop perspective, [and which employs] a direct or inferred image of Jesus, which implies the old circular sun/Son narratives of death and resurrection.

Paul Crumbley reads the poem in a political context and in the context of other poems about prisons, observing:

The line of reasoning that unites resistance with sovereignty is wonderfully productive across Dickinson’s oeuvre and central to her political epistemology.

This poem, then,

presents the loss of liberty as a direct result of diminished resistance. This particular speaker goes so far as to state that without resistance, liberty ceases to be a realistic possibility.

Maryanne Garbowsky reads the last stanza as recalling “the terrors of agoraphobia,” a psychological condition characterized by fear of public and open spaces.

The context Cristanne Miller offers for this poem suggests another approach. She notes an allusion to Lord Byron’s poem, “The Prisoner of Chillon” (1816), in which the prisoner claims, “My very chains and I grew friends.” A few years later, Dickinson wrote to her cousin Lavinia about her confinement due to illness and quipped:

You remember the Prisoner of Chillon did not know Liberty when it came, and asked to go back to Jail (L293).

Seeing this “friendship” in an eastern light, Yanbin Kang finds in this poem a description of

meditation-like repose … [Dickinson] seeks a “passive” “Content” rather than “Hope,” which her speaker achieves through self-cultivation within a narrow space, in a way that Daoism and Chan Buddhism would conceive as an admired negative action. Zhuangzi illustrates the importance of this principle via the negative example of a fool dying from exhaustion. Caught up in running away in order to avoid his own shadow and footprints, the fool remains unaware that once he stands still, they will disappear.

Sources

Crumbley, Paul. “Democratic Politics.” Emily Dickinson in Context. Ed. Eliza Richards. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013: 179-187, 183.

Dickinson, Emily. Emily Dickinson’s Poems, As She Preserved Them. Ed. Cristanne Miller. Cambridge: The Belknap Press, of Harvard University, 2016, 758, n. 209.

Garbowsky, Maryanne. The House without the Door: A Study of Emily Dickinson and the Illness of Agoraphobia. Rutherford, N. J.: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1989, 85-87.

Kang, Yanbin. “Dickinson’s ‘Power to die’ from a Transcultural Perspective.” The Emily Dickinson Journal, 22, 2 (2013): 65-85, 68.

Yin, Joanna. “Circle Imagery.” An Emily Dickinson Encyclopedia. Ed. Jane Donahue Eberwein. Westport, CT.: Greenwood Press, 1998, 45.

See also: Wohlpart, James. “A New Redemption: Emily Dickinson's Poetic in Fascicle 22 and ‘I Dwell in Possibility.’” South Atlantic Review 66.1 (Winter, 2001): 50-83.

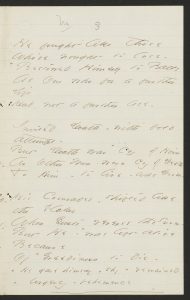

He fought like those Who’ve nought to lose - (F480, J759)

He fought like those

Who've nought to lose -

+Bestowed Himself to Balls

As One who for a further

Life

Had not a further Use -

Invited Death – with bold

attempt -

But Death was +Coy of Him

As Other Men, were Coy of Death.

To Him – to live – was Doom -

His Comrades, shifted like

the Flakes

When Gusts reverse the Snow -

But He – +was left alive

Because

Of +Greediness to die -

+ He gave himself + shy + remained +Urgency – • Vehemence

EDA manuscript: "Originally in Poems: Packet XXXI, Fascicle 23, Houghton Library – (165b). Includes 20 poems, written in ink, ca. 1862. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. First published in Unpublished Poems (1935), 6, with the alternatives for lines 11 and 12 (“Vehemence”) adopted."

Dickinson placed this poem second in Fascicle 23, after the opening poem “Because I could not stop for Death,” a poem with many and various readings. In an essay on “Dickinson’s Fascicles,” Sharon Cameron discusses “Because I could not stop for Death,” and how its meaning changes when read in relation to many of the poems in the fascicle that are not just about the apprehension of death but the apprehension of the death of a lover. Cameron does not specifically discuss “He fought like those Who’ve nought to lose;” and in fact, its imagery of “Balls,” “Comrades,” and “Flakes” links this poem to other poems in this period about the deaths of soldiers in the Civil War, though, of course, soldiers were likely someone’s beloved too.

Still, the poem does not express a lover’s anguish over this death, or failure to die; it is much more detached and rather curious about the “Greediness,” or as the variants have it, “Urgency” and “Vehemence to die” that allow the man to fight fearlessly. Yanbin Kang provides an approach to Dickinson’s poem through the Chan Buddhist notion of nullifying the power of death over life. Kang notes that in this poem

Dickinson paradoxically employs martial images to express self-denial and self-conquest, which enable one to achieve repose. … This idea relates to what is called Great Death in Chan Buddhism, which is deemed a necessity for achieving Great Life. … Dickinson may have been influenced in such thinking by Thoreau … For Dickinson, readiness to die emboldens us, effectively cancelling fear of aggression or threat.

Sources

Cameron, Sharon. “Dickinson’s Fascicles.” The Emily Dickinson Handbook. Eds. Gudrun Grabher, Roland Hagenbüchle, Cristanne Miller. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1998: 138-60, 149-50.

Kang, Yanbin. “Dickinson’s ‘Power to die’ from a Transcultural Perspective.” The Emily Dickinson Journal, 22, 2 (2013): 65-85, 75-76.