On Choosing the Poems

As we suggested in the Overview to this week’s post, Dickinson was profoundly affected by contemporary cultural attitudes about women of genius. In her essay, “A Damned Mob of Corinnes: Hawthorne and the Daughters of de Staël,” Renée Bergland reviews the history of these attitudes in relation to the french author, Madame de Stael. Bergland focuses on de Stael’s popular novel, Corinne, about a dark-haired and passionate female poet who loses her gift and pines away when the English lord she loves marries her blonde, bland and modest sister.

As we suggested in the Overview to this week’s post, Dickinson was profoundly affected by contemporary cultural attitudes about women of genius. In her essay, “A Damned Mob of Corinnes: Hawthorne and the Daughters of de Staël,” Renée Bergland reviews the history of these attitudes in relation to the french author, Madame de Stael. Bergland focuses on de Stael’s popular novel, Corinne, about a dark-haired and passionate female poet who loses her gift and pines away when the English lord she loves marries her blonde, bland and modest sister.

Published in 1807, Corinne set a standard for the artistic female and was very influential for 19th century women writers in France, England and the US. Bergland finds that popular US writers like “Catharine Sedgwick and Lydia Maria Child were relatively untroubled by their identification with Corinne in the 1820s and 1830s.” Indeed, the great writer, Margaret Fuller, was known as “the Yankee Corinne.” But “[b]y the 1860s and 1870s, Louisa May Alcott and Constance Fenimore Woolson would describe genius as a fatal disease.”

Bergland calls the period of 1850-1860 “the crucial decade” when anxiety about the figure of Corinne reached a fever pitch and turned. It was in 1855 that Nathaniel Hawthorne famously wrote to his publisher, William Ticknor, castigating that “d—d mob of scribbling women,” who were outselling male writers.

And though Hawthorne admired the writing of many contemporary women, like Grace Greenwood, Fanny Fern, and Julia Ward Howe, he compared women’s publication of their works to “prostitution.” Others shared his feelings.

As in so many other ways, Dickinson’s father Edward was a bellwether of mixed and misogynist attitudes when it came to questions of gender and genius, attitudes he must have communicated to his perceptive daughter. Bergland notes that in 1826, Edward met Catharine Sedgwick, a leading writer of the day, and wrote in his journal that he felt

a conscious pride that women of our own country … are emulating not only the females, but also the men of England & France & Germany & Italy in works of literature.

But he was also disturbed: “I should be sorry to see another Madame de Staël.” This ambivalence emerges in Dickinson’s remark to Thomas Higginson about her father:

He buys me many books, but begs me not to read them, because he fears they joggle the mind. (L261, 25 April 1862)

The poems we have chosen for this week meditate on issues of fame, freedom, despair in love and marriage, misunderstanding, and isolation, all of the obstacles facing women of genius in 1862.

I would not paint – a picture – (F348A, J505)

I would not paint – a picture –

I’d rather be the One

It’s +bright impossibility

To dwell – delicious – on –

And wonder how the fingers feel

Whose rare – celestial – stir –

+Evokes so sweet a torment –

Such sumptuous – Despair –

I would not talk, like Cornets –

I’d rather be the One

Raised softly to +the Ceilings –

And + out, and easy on –

Through Villages of Ether –

Myself + endued Balloon

By but a lip of Metal –

The pier to my Pontoon –

Nor would I be a Poet –

It’s finer – Own the Ear –

Enamored – impotent – content –

The License to revere,

A + privilege so awful

What would the Dower be,

Had I the Art to stun

myself

With Bolts – of Melody!

+fair + provokes

+ Horizons + by – +upborne • upheld • sustained

+ luxury

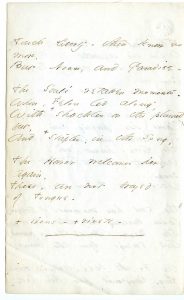

EDA manuscript: "Originally in Amherst Manuscript #fascicle 85. First published in Bolts of Melody (1945), xxxi, with the alternative for line 11 adopted. Courtesy of Amherst College, Amherst, MA."

This is the second poem in Fascicle 17, which Dickinson put together sometime in the summer of 1862. It shares sheet one with the first poem in the fascicle, “I dreaded that first Robin, so” (F347, J348). Its final, arresting line gives the title to the popular 1945 selection of Dickinson poems, Bolts of Melody, edited by Mabel Loomis Todd and her daughter, Millicent Todd Bingham. Cristanne Miller notes that Dickinson “would have known several poems linking the arts of painting, music, and poetry (e.g., Keats’s “Ode to a Nightingale,” 1819).” Susan Leiter observes that

Cristanne Miller notes that Dickinson “would have known several poems linking the arts of painting, music, and poetry (e.g., Keats’s “Ode to a Nightingale,” 1819).” Susan Leiter observes that

Dickinson was a skilled cartoonist and accomplished pianist who composed original pieces, as well as a lover of the visual arts and of music. So she had some experience as maker and receiver in all three artistic realms.

Helen Vendler adds Keats’s “Ode on a Grecian Urn” to this genre, and notes that Dickinson reverses the usual comparison between the sister arts, asserting that it is better to be the audience of the art than the artist. But, Vendler goes on,

because of her witty and beautiful descriptions of the various arts, we cannot help believing that it is an artist who is speaking to us.

Scholars focus on the last stanza’s description of hearing poetry, in which the speaker wishes to become an “ear” to receive the poem aurally. The experience is described in words that are bodily and profound: “Enamored – impotent – content,” “revere,” “privilege/luxury so awful”—that is, full of awe, “stun,” and finally, the startling image of the poet as a veritable Jove or Jehovah, hurling “Bolts – of Melody.” We might recall that the Puritans believed that grace came via the ear, through hearing the words of a divinely inspired minister. Compare another use of the ear image from “I felt a Funeral, in my Brain,” F340, J280), in which the speaker is hearing the sounds of death:

And then I heard them

lift a Box

And creak across my Brain

With those same Boots of

Lead, again,

Then Space – began to toll,As all the Heavens were

a Bell,

And Being, but an Ear …

Scholars also find erotic and sexualized imagery throughout this poem, suggested in part by the word “Dower,” which, according to Dickinson’s Lexicon, could mean the property a man leaves his widow, the property a bride brings to her marriage, or the gift of a husband to his wife. The power of artists appears “masculine” for being active, while the audience seems feminine for being passive. Suzanne Juhasz and Cristanne Miller call the final image

autoerotic … an orgasmic moment that combines the phallic “Bolts” with the more feminine (in its pleasing tunefulness) “Melody.”

Cynthia Wolff interprets this amazing moment as a “tongue-in-cheek assertion of the necessarily ‘androgynous’ nature of the Poet,” which is especially important to the woman poet who, as artist, must take on active, assertive and conventionally “masculine” qualities. This reading echoes the thinking of the German philosopher, Arthur Schopenhauer, mentioned in this week’s post, who posited the existence of a “third sex” to describe the artist. Feminist critic Carolyn Heilbrun also championed androgyny as a means of including women in genius.

Sources

Dickinson, Emily. Emily Dickinson’s Poems, As She Preserved Them. Ed. Cristanne Miller. Cambridge: The Belknap Press, of Harvard University, 2016, 754.

Juhasz, Suzanne and Cristanne Miller. “Performances of Gender in Emily Dickinson’s Poetry.” Cambridge Companion to Emily Dickinson. Ed. Wendy Martin. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002: 107-128, 125.

Heilbrun, Carolyn. Towards a Recognition of Androgyny. New York: W. W. Norton, 1973.

Leiter, Sharon. Critical Companion to Emily Dickinson: A Literary Reference to her Life and Work. New York: Facts on File, 2007, 135-36.

Vendler, Helen. Dickinson: Selected Poems and Commentaries. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University, 2010, 148-50.

Wolff, Cynthia. Emily Dickinson. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co., Inc. 1988, 171-72.

The Soul has Bandaged moments – (F360A, J512)

The Soul has Bandaged moments –

The Soul has Bandaged moments –

When too appalled to stir –

She feels some ghastly Fright

come up

And stop to look at her –

Salute her, with long fingers –

Caress her freezing hair –

Sip, Goblin, from the very lips

The Lover – hovered – o’er –

Unworthy, that a thought so

mean

Accost a Theme – so – fair –

The soul has moments of escape –

When bursting all the doors –

She dances like a Bomb, abroad,

And swings opon the Hours,

As do the Bee – delirious borne –

Long Dungeoned from his Rose –

Touch Liberty – then know no

more –

But Noone, and Paradise

The Soul’s retaken moments –

When, Felon led along,

With +shackles on the plumed

feet,

And +staples, in the song,

The Horror welcomes her,

again,

These, are not brayed

of Tongue –

+ irons – + rivets –

EDA manuscript: "Originally in Amherst Manuscript #fascicle 85. First published in Bingham, Ancestors’ Brocades (1945), 331, lines 1-2; Bolts of Melody (1945), 244-45, as three stanzas of 10, 8, and 6 lines, with the alternative for line 22 adopted. Courtesy of Amherst College, Amherst, MA."

Dickinson included this poem in Fascicle 17, on sheet six, the next to the last poem in the group. Thus, Dickinson herself put it into relationship with “I would not paint – a picture –”, the second poem in the fascicle, and the first in our cluster. It is also connected to the first poem in Fascicle 17 by the word “salutes,” which suggests the military discipline of wartime.

In three parts, this poem narrates three experiences of the “Soul:”

1)“Bandaged moments” of intense wounding when it is paralyzed by Fright, a personified abstraction that becomes a horribly tactile gothic “Goblin” sipping—what?— from lips “The Lover – hovered – o’er –,” a line of immense linguistic craft.

2) Then, the opposite experience: delirious “moments of escape,” “liberty,” even “paradise,” expressed in one of the most memorable self-descriptions in a huge store of memorable imagery: “She dances like a Bomb, abroad …” We should note that in a letter to Thomas Wentworth Higginson written in August 1862, Dickinson uses similar imagery to describe her attempts to impose self-discipline in the process of writing:

I had no Monarch in my life and cannot rule myself, and when I try to organize – my little Force explodes – and leaves me bare and charred – (L271).

It is hard not to think of events of the Civil War as a context for this poem and its explosive imagery: the devastation of the siege of Fort Donelson and the raid on Harper’s Ferry discussed in this week’s post; and the death of Frazar Stearns, which will happen next week. This context suggests that this poem is not only about “the suspicion of infidelity,” as Helen Vendler asserts, but also about Dickinson’s experience of her genius, an explosive force that emanates from a deep wound or “terror,” which sometimes manages to escape its captivity (by social convention, conformity, scrutiny, the gendered body). When it does, it is like the promiscuous and fertilizing “bee” finding its “Rose” and losing itself in bliss.

3) But bliss, paradise and “noon” cannot last. In the third section, the soul is “retaken” as a “Felon.” What crime has this female Soul committed against the world? “Perhaps,” as the speaker says in another poem in this Fascicle, “I asked too large – / I take – no less than skies–” (F360A, J512). That the crime concerns the hubris of writing poetry seems borne out by the description of the recapture: “With shackles/irons on the plumed feet, / And staples/rivets, in the song …” and the rhyming of “along,” “song” and “Tongue.” The soul is feathered, like a bird, to soar (compare Margaret Fuller’s depiction of genius in the introduction) but its feet are crippled and crucified, its voice reduced to the “braying” of animals.

Sources

Dickinson, Emily. The Letters of Emily Dickinson. Eds. Thomas Johnson and Theodora Ward. 3 vols. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1958, 414-15.

Dickinson, Emily. Emily Dickinson’s Poems, As She Preserved Them. Ed. Cristanne Miller. Cambridge: The Belknap Press, of Harvard University, 2016.

Vendler, Helen. Dickinson: Selected Poems and Commentaries. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University, 2010, 161-64.

They shut me up in Prose (F445A, J613)

They shut me up in Prose –

As when a little Girl

They put me in the Closet –

Because they liked me “still” –

Still! Could themself have peeped –

And seen my Brain – go round –

They might as wise have lodged

a Bird

For Treason – in the Pound –

Himself has but to will

And easy as a Star

Look down opon Captivity –

And laugh – No more have I –

EDA manuscript: "Originally in Packet XXXIV, Fascicle 21, ca. 1862. First published in Unpublished Poems (1935), 34, with the alternative not adopted. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA."

This poem of defiance and resistance employs some of the imagery we have seen in earlier poems in this group. It implies that female genius cannot express itself without a struggle. The speaker, identifiable as a “girl,” is “shut up,” with the double meaning of made silent and locked into a room defined as “Prose.” This could refer to the prosaic expectations of women in her small town, chained to domesticity, subservience and humility, or the denial of her intellect imaged as her restless “Brain,” obstacles other women of genius experienced as well. Although it has been suggested that this poem describes a traumatic childhood experience of Dickinson’s, we have no definitive evidence of it. We do know, from their biographies, that George Sand (1804-1876), pen name for the French author Aurore Dudevant, and Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806-1861), the English poet, both favorites of Dickinson, suffered restraint and repression of their gifts in their childhoods.

There is also bird and crime imagery here. The physical captivity of the girl’s body cannot fetter her mind or spirit, which she compares to the attempt to keep a bird “For Treason – in the Pound.” According to Dickinson’s Webster’s,

Treason is the highest crime of a civil nature of which a man can be guilty.

It is a deliberate flouting and betrayal of the government, of patriarchal rule. Despite the speaker’s defiance, birds, which Dickinson connects with the artist figure, can be captured: the caged bird was a frequent symbol of women imprisoned by marriage. Still, the bird in this instance looks down from a height and laughs at “Captivity,” just as the speaker does, or wishes to do.

Dickinson copied this poem into Fascicle 21 during 1862 (the year after Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s death, we might note), and it appeared on the left hand page opposite another poem relevant to our week’s theme. “This was a Poet – It is That” (F446A, J448) describes the process of genius, how the poet (referred to here as “He” but in many ways resembling Dickinson)

Distills amazing sense

From Ordinary Meanings –

And Attar so immense.

Sources

Hallen, Cynthia, ed. Emily Dickinson Lexicon. Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University, 2007.

Leiter, Sharon. Critical Companion to Emily Dickinson: A Literary Reference to her Life and Work. New York: Facts on File, 2007, 203-204.

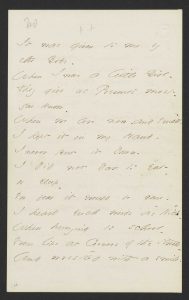

It was given to me by the Gods (F455A, J454)

It was given to me by

It was given to me by

the Gods –

When I was a little Girl –

They give us Presents most –

you know –

When we are new – and small.

I kept it in my Hand –

I never put it down –

I did not dare to eat –

or sleep –

For fear it would be gone –

I heard such words as “Rich” –

When hurrying to school –

From lips at Corners of the Streets –

And wrestled with a smile.

Rich! ‘Twas Myself – was

rich –

To take the name of Gold –

And Gold to own – in solid

Bars –

The Difference – made me

bold –

EDA manuscript: "Originally in Packet XXXIV, Fascicle 21, ca. 1862. First published in Bolts of Melody (1945), 83-84, from a transcript of A (a tr360), as four quatrains. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA."

Dickinson also copied this poem into Fascicle 21 as the last in the group, perhaps summing up its themes. It contains, for Dickinson, a rather straightforward narrative of “calling” or “vocation,” to use Puritan religious terms about one's earthy “work”or “occupation” as part of one's progress towards salvation. In this poem, the speaker recounts receiving her “gift” of genius. She says outright that it is from “the Gods” and so assigns this genius a divine source, something out of her control and beyond human reckoning. But notice the pantheism in her phrasing: not given by one God or the God, but by a raft of them, as if they are sitting majestically in Olympus, drinking nectar served by their cup bearer, Ganymede.

It is this gift that makes her “different,” and in this instance the speaker embraces her difference, even though it sets her apart. The poem characterizes this difference with the simple adjective: “Rich”—genius as a metaphorical form of wealth. These riches are both metaphorically material—“solid Bars” of gold the speaker owns, and also a description OF the self, “the name” the self takes for itself that she hears whispered by townspeople. In fact, it is this difference that “made me bold,” the speaker discloses; it gave her the strength to pursue her genius. For once, there is little to no ambivalence here, suggested by the exact rhymes of “Gold” and “bold” that conclude the poem.

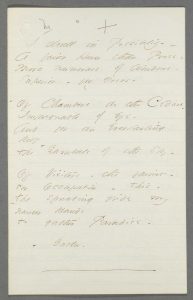

I dwell in possibility (F466A, J657)

I dwell in Possibility –

I dwell in Possibility –

A fairer House than Prose –

More numerous of Windows –

Superior – for Doors –

Of Chambers as the Cedars –

Impregnable of eye –

And for an everlasting

Roof

The Gambrels of the Sky –

Of Visitors – the fairest –

For Occupation – This –

The spreading wide my

narrow Hands

To gather Paradise –

EDA manuscript: "Originally in Poems: Packet XIX, Fascicle 22, dated ca. 1862. First published in Further Poems (1929), ed. Bianchi and Hampson, 30, with the alternative adopted. Courtesy of the Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA."

Dickinson copied this poem into Fascicle 22, also dated to 1862 and following Fascicle 21, which contained the previous two poems. The first poem in this fascicle is “A Prison gets to be a friend” (F456A, J652), which picks up the imagery of captivity. And the penultimate poem is “He fumbles at your Soul” (F477A, J315), a harrowing poem that ends with the hurling of an “imperial Thunderbolt – / That peels your naked soul,” an image that recalls the marvelous image, though in a more positive register, of the poet stunning herself with “Bolts of Melody,” from “I would not paint a picture.”

Readers have called this poem a “manifesto” that compares poetry, referred to obliquely as “Possibility,” to prose as an inferior dwelling place with decidedly inferior ventilation. The “cedars” referred to in the second stanza evoke a verse from Psalms 104:16:

The trees of the Lord are full of sap: the cedars of Lebanon which He hath planted,

and suggest the brimming, divinely ordained vitality of poetry.

“Gambrels” are “hipped roofs” (Webster’s) sloped on each side, which were traditionally used in building barns and could be seen in Amherst.

Here, in this poem, the homely and familiar become the architecture of the heavens. It is in this airy structure that the speaker can take up her genius and pursue her “Occupation,” or “calling,” which consists of “gather[ing] paradise,” even though her hands are “narrow” and small.

Here, in this poem, the homely and familiar become the architecture of the heavens. It is in this airy structure that the speaker can take up her genius and pursue her “Occupation,” or “calling,” which consists of “gather[ing] paradise,” even though her hands are “narrow” and small.

So much of Dickinson’s dynamic poetics can be illustrated by her equation of them with “possibility.” Still, we hear a darker note in the word “Impregnable,” which refers to the character of this dwelling as visually invisible. Yet, it is usually fortresses that are described as “impregnable,” so who is the enemy and where is the besieging army? The sexual connotation of this word cannot be avoided. Could Dickinson be suggesting that her dwelling is protected from invasion; that it has no male or masculine, impregnating or violating source?

H. Jordan Landry argues the opposite, that though masculine power can be terrifying in Dickinson’s poems, the “power available in poetic inspiration is also posited as masculine.” The transcendence

of restrictive boundaries … initiated by the masculine is commensurate with a key goal of Dickinson’s poetics: the attainment of “Possibility.”

There is another way to look at this set of images. In Anne Bradstreet’s poem, “The Author to her Book,” written after she first saw the volume of her poems published by her brother-in-law in London in 1650, she describes it deprecatingly as an “ill-formed offspring of my feeble brain,” turns it out of the house to manage on its own, and cautions:

If for thy father asked, say thou hadst none.

While this renders the book-child illegitimate, it also makes it completely and undeniably hers, a totally female creation.

Sources

Hallen, Cynthia, ed. Emily Dickinson Lexicon. Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University, 2007.

Landry, Jordan H. “The Masculine Role.” An Emily Dickinson Encyclopedia. Ed. Jane Donahue Eberwein. Westport, CT.: Greenwood Press, 1998, 192-93.

Leiter, Sharon. Critical Companion to Emily Dickinson: A Literary Reference to her Life and Work. New York: Facts on File, 2007. 96-97.

Vendler, Helen. Dickinson: Selected Poems and Commentaries. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University, 2010, 222-24.

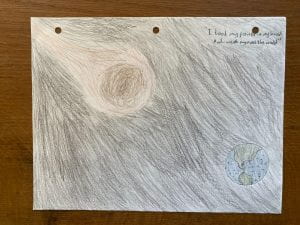

I took my power in my hand (F660A, J540)

I took my Power in my Hand –

And went against the

World –

‘Twas not so much as

David – had –

But I – was twice as bold –

I aimed my Pebble – but

Myself

Was all the one that fell –

Was it Goliah – was too

large –

Or was myself – too small?

EDA manuscript: "Originally in Poems: Packet XVII, Mixed Fasciles, ca. 1862. First published in Poems (1891), 56. Courtesy of the Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA."

This poem links genius with the boldness we saw in “It was given to me by the gods” (F455A, J454) but evokes a much more qualified experience of that power. The speaker takes the Biblical story of David and Goliath from 1 Samuel 17:23-50 as a conceit for her own small resistance to the much larger world of convention and androcentrism. In the Biblical story, David calls on God to help him defeat the giant Goliath, thereby showing that Saul, who has refused to face Goliath, does not deserve to be king of the Israelites, while David does. David is also the singer of the Psalms, a connection to the poem’s speaker’s literary vocation.

While the speaker says she does not have “so much as David – had,” she also says she “was twice as bold–” and dared more. But she finds the pebble she releases from her slingshot hits and fells “Myself.” She wonders, was the giant she faced “too large” or was “myself – too small?” In appropriating a parable about male courage and daring, Dickinson places herself in the line of ancient kings and divinely inspired singers. This story inverts the usual terms of martial combat: it is not sheer physical strength, but moral conviction and dependence on the divine, something larger and outside of oneself, that wins the day.

Or is this a parable about hubris, about overreaching? Vivian Pollak argues:

Out of this self-critical dialogue between arrogance and humility, a third voice emerges: the voice of the poet mediating this conflict through language which calls attention to the instability of its ironic mode.

Sources

Pollak, Vivian. “The Second Act: Emily Dickinson’s Orphaned Persona.” Nineteenth-Century Women Writers of the English-Speaking World. Ed. Rhoda B. Nathan. Contributions to Women’s Studies, no. 69. New York: Greenwood Press, 1986, 159-69, 163.

Sources

Bergland, Renée. “A Damned Mob of Corinnes: Hawthorne and the Daughters of de Staël,” Nathaniel Hawthorne Review 42.1 (Spring 2016): 95-120.