This week’s focus is Winter, inspired by this season of endings, of dormancy and darkness, and also of the holidays of lights—Christmas, Hanukkah, Kwanza, Diwali—with their candles, oil lamps, evergreens and messages of peace despite contemporary contamination by consumerism. It was heartening to hear several stories in the media calling for “giftless” holidays or giving the gift of presence and intimacy or homemade gifts. It’s a good time to think of renewing our commitments to making and nourishing connections and building bridges not walls.

Dickinson calls winter the “Finland of the Year” (J1696), and it is part of her extensive seasonal imagery. As we will see in our explorations of her attitudes in letters and the symbolism in her poetry, winter signals cold, deprivation, isolation and death. But it also suggests purity through the important images of whiteness, clarity, strength, independence and perseverance. As critic L. Edwin Folsom commented,

Winter, for Emily Dickinson, was a primary source of her realism.

Winter is also the time in which we lay up the seeds and resources for next year’s resurgence. For those of us in the north, it signals the end of the year and also the return of the light after the Winter Solstice. Thus, it is fitting that this is the last post in this year-long project of immersing ourselves in Dickinson’s world for the eventful year of 1862. We will reflect on the year’s process and also look forward to new beginnings in the buried roots of wonder.

“Strong and Healthy as a Northern Breeze”

Springfield Republican, December 27, 1862

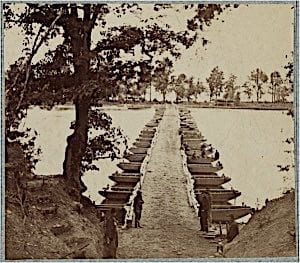

Progress of the War, page 1

“Public attention has been turned from the auxiliary situation for some days by an attempt of the majority of the Senate to force a reconstruction of the cabinet for the sake of dropping out Mr. Seward, which was temporarily successful, but terminated in the return of the secretaries to their previous positions. The first shock of the Fredericksburg disaster [the battle fought Dec 11-15] has been overcome, and since it is seen that the losses were less than at first supposed, that the army is not demoralized by the failure, and since Gen. Burnside assumes the whole responsibility of the experiment, hope begins to be entertained that the winter campaign in Virginia has not been terminated by it, and that some means of reaching Richmond may be discovered more hopeful than dashing our gallant army in places against impregnable fortifications.

Success of Physical Culture at Amherst College, page 2

“We are glad to receive from time to time favorable accounts of the working of the gymnastic system which has been adopted by the trustees of Amherst College. During the term, and indeed during the year, the health of the students has been remarkably uniform. Not a single case of fever has occurred in college during the year. Of 178 students who were present during the fall term, only five were at any time on the sick list for more than two days.”

Late from China and Japan: Russia sending troops to China—The Revolution in Japan, page 5

“It was rumored that a large body of Russian troops were coming from the Amoor to aid the Chinese government in the recapture of Ningpoo, and to put down the rebellion. James’ Herald of November says the revolution in Japan is complete. The tycoon [“taikun” or great commander] has been stripped of nearly all his special privileges.”

Books, Authors and Arts, page 7

“Of the remaining poems of [Bayard Taylor’s new volume], “Passing the Sirens” is the best. It is as strong and healthy as a northern breeze, and too full of life and power to be anything less than an offspring, most classically disguised, of personal experience. We trust the volume may find many appreciative readers, and that abundant room may be made for the author in the high place which belongs to him as an American poet.”

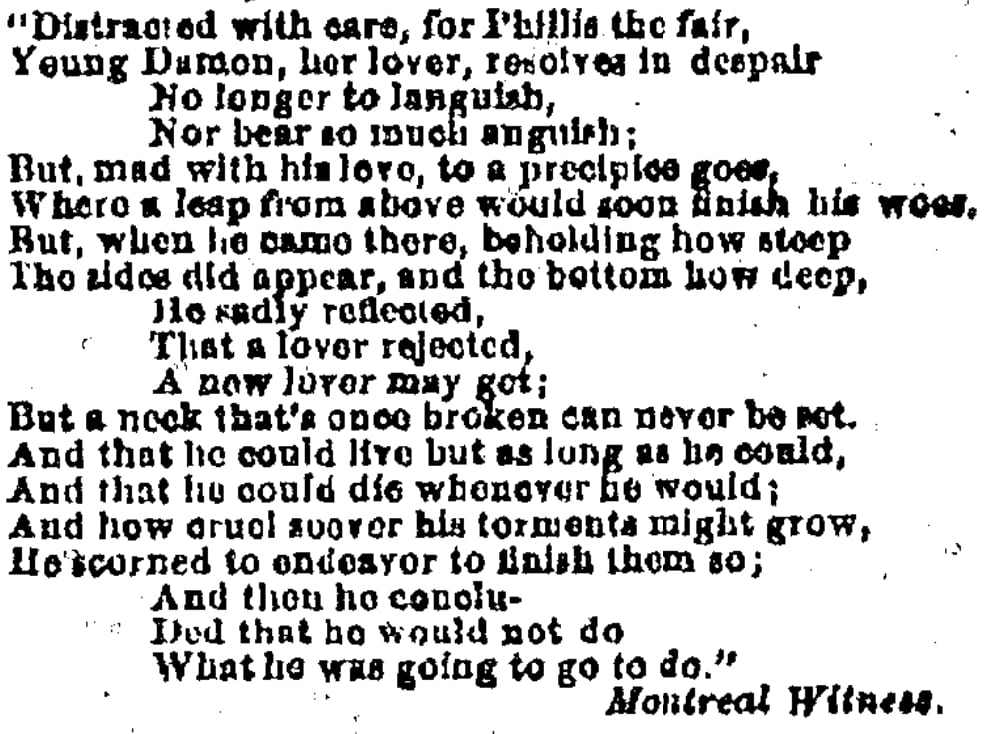

Original Poetry: Dying for Love, [by William Walsh (1662-1708) English poet and friend of Alexander Pope] page 7

Atlantic Monthly, December 1862

The Fossil Man, page 670 [by C. L. Brace (1826-1890), an American social reformer]

“What a mysterious and subtile pleasure there is in groping back through the early twilight of human history! The mind thirsts and longs so to know the Beginning: who and what manner of men those were who laid the first foundations of all that is now upon the earth: of what intellectual power, of what degree of civilization, of what race and country. We wonder how the fathers of mankind lived, what habitations they dwelt in, what instruments or tools they employed, what crops they tilled, what garments they wore. We catch eagerly at any traces that may remain of their faiths and beliefs and superstitions; and we fancy, as we gain a clearer insight into them, that we are approaching more nearly to the mysterious Source of all life in the soul.”

Harper’s Monthly, December 1862

Editor’s Easy Chair, page 134

“The letter of Garibaldi to the British nation contrasts strangely in the purity of its appeal to the loftiest principle with the apparent character and conduct of the people to whom it is addressed. Yet the contrast is between the heroic faith of Garibaldi and the hesitating, treacherous timidity of the British Government, and not between the instinct of the Italian fils du people and that of the people of England. When you hear the high appeal, breathed in passionate music, it is impossible not to think of Titania and Bottom [from Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream, Act IV.1. An angry King Oberon casts a spell on Queen Titania, so that she falls madly in love with Bottom, a weaver who has been given the head of an ass.] When you turn from English history, or the London newspaper of today, to listen to that clear Southern voice intoning the principles and ideas which it is the glory of men to have uttered centuries ago, it is almost if you have heard that voice itself out of history, vague, remote, illusive.”

“Better than a Summer”

“The Puritan Governor interrupting the Christmas Sports,” c. 1883

The last week in December was likely a cold and perhaps dreary time in the Dickinson household. The earliest New England Puritans were not keen on Christmas, which they claimed had no scriptural foundation and was celebrated in Old England by carnival-like activities they found reprehensible. They outlawed Christmas, but by the mid-eighteenth century, it had become a popular holiday in the US embraced by Congregational Churches as a time for formal observance. The December 27, 1862 issue of the Republican reported:

Here at home we see the usual demonstrations on the part of the whole people for a spirited and bona fide celebration of the holiday rites,

but we have no idea how the Dickinson family of the Homestead spent the holiday, if at all.

Dickinson’s letters from this time indicate that she was preoccupied with Samuel Bowles’s return from Europe in mid-November, and her imagery in those letters sheds light on her broader attitude towards winter. After his return, Bowles visited the Homestead, but Dickinson refused to come down and see him, and sent this note instead:

Dear friend

I cannot see you. You will not less believe me. That you return to us alive, is better than a Summer. And more to hear your voice below, than News of any Bird.

Emily. (L276)

In a longer letter sent at the same time, Dickinson explained:

Because I did not see you, Vinnie and Austin, upbraided me – They did not know I gave my part that they might have the more.

The rest of the letter is elliptical and ends on a note of shared suffering and renunciation with these two lines:

Let others – show this Surry's Grace -

Myself – assist his Cross. (L277)

Dickinson’s description of Bowles’s safe return as “better than a Summer” places it within her seasonal symbolism where she measures it against her favorite season of the fullest sun, light, warmth, life, even eternity. Evoking related symbolism in other letters, Dickinson associates winter with death, as in this (melo)dramatic outburst to the Hollands in November 1858:

I can't stay any longer in a world of death. Austin is ill of fever. I buried my garden last week – our man, Dick, lost a little girl through the scarlet fever. I thought perhaps that you were dead, and not knowing the sexton's address, interrogate the daisies. Ah! dainty – dainty Death! Ah! democratic Death! Grasping the proudest zinnia from my purple garden, – then deep to his bosom calling the serf's child!

Say, is he everywhere? Where shall I hide my things? Who is alive? The woods are dead. Is Mrs. H. alive? Annie and Katie – are they below, or received to nowhere? (L195)

Later in her life, Dickinson will reverse this symbolism, suggesting that it is death that brings winter no matter what season it is, as in this description of her mother’s death from 1882:

She slipped from our fingers like a flake, and is now part of the drift called “the infinite.” (L785)

In her classic study of Dickinson’s imagery, Rebecca Patterson saved the last chapter for an explication of the symbolism of “The Cardinal Points,” which Barton Levi St. Armand expanded into what he calls “Dickinson’s mystic day.” Patterson argues that Dickinson learned the power of symbolism from Emerson, who asked in his great essay Nature (1836),

is there no intent of an analogy between man’s life and the seasons? And do the seasons gain no grandeur or pathos from that analogy?

Patterson finds that Dickinson

was in fact a naïve symbolist who … used this symbolism like a second language, or a species of shorthand

but often diverged from Emerson’s ideas. She associated “North” and “northern” and its equivalents like “Arctic” and “Polar” with night, specifically midnight, winter and elements like sleet, snow, frost, glaciers, freezing, icicles, darkness, blindness, death, and the color white

as an arbitrary (cultural) identification of chastity or virginity.

As we discussed in our earlier post on White, however, these cultural associations are hardly “arbitrary” at all.

In many symbol systems, including Dickinson’s, the north and winter have some positive attributes and are associated with masculinity, maturation, power, hardihood, independence, female virtue, and faithfulness. Patterson suspects Dickinson absorbed these ideas from the writings of John Ruskin, a prominent English art critic, which, in a letter from April of this year, she told Higginson she was reading.

In several of his works, Ruskin praises northern superiority, which flourishes in the cold and, like the hemlock trees surrounding the Homestead, is strengthened by the deprivations of winter. Not surprisingly, given her skepticism, the north is where Dickinson locates her God, but it is also the regions associated with Satan in Milton’s Paradise Lost. In several poems, she refers to winter and “snow” as a “Prank,” a joke God or Nature plays on humans: see “The tint I cannot take” (F696, J627) and “These are the days that Reindeer Love” (F 1705, J1696).

Finally, to bring this back to Dickinson’s relationship to Bowles, Patterson traces a set of poems and letters she wrote to him in 1861-63 beginning with “Title divine is mine” (F194 , J1027) in which Patterson surmises that “snow” refers to sexual purity and the martyrdom of renunciation. We might contest this biographical reading with its symbolic “shorthand” as reductive, though Patterson concedes:

These poems of northern cold and darkness always imply their opposites.

We have only to think of the “White Heat” of creativity that also characterizes this period in Dickinson’s life.

(the last!) Reflection

Ivy Schweitzer

It has been a year of unmitigated creative fun and revelations for me as I blogged every week about Dickinson’s life and writing in 1862!

It has been a year of unmitigated creative fun and revelations for me as I blogged every week about Dickinson’s life and writing in 1862!

I recognize how lucky I am to have had the luxury of spending a year with one poet who so richly deserves and repays our closest attention. To be able to read extensively and deeply in the biographical materials has been essential. And to dip into the newspapers and periodicals Dickinson most likely read on a daily basis has sharpened my sense of the issues surrounding her, in the air and on people’s lips and minds. And not only the substance of the news, but its form: the large, packed pages of print, sometimes broken by a tiny square of poetry; reports of grisly war next to fluff pieces reinforcing Victorian sex-gender conventions about “the perfect girl,” “How husbands should act,” “How wives should act,” and so on. Serious news next to the latest in fashion, and in periodicals, now-famous writers published without by-lines.

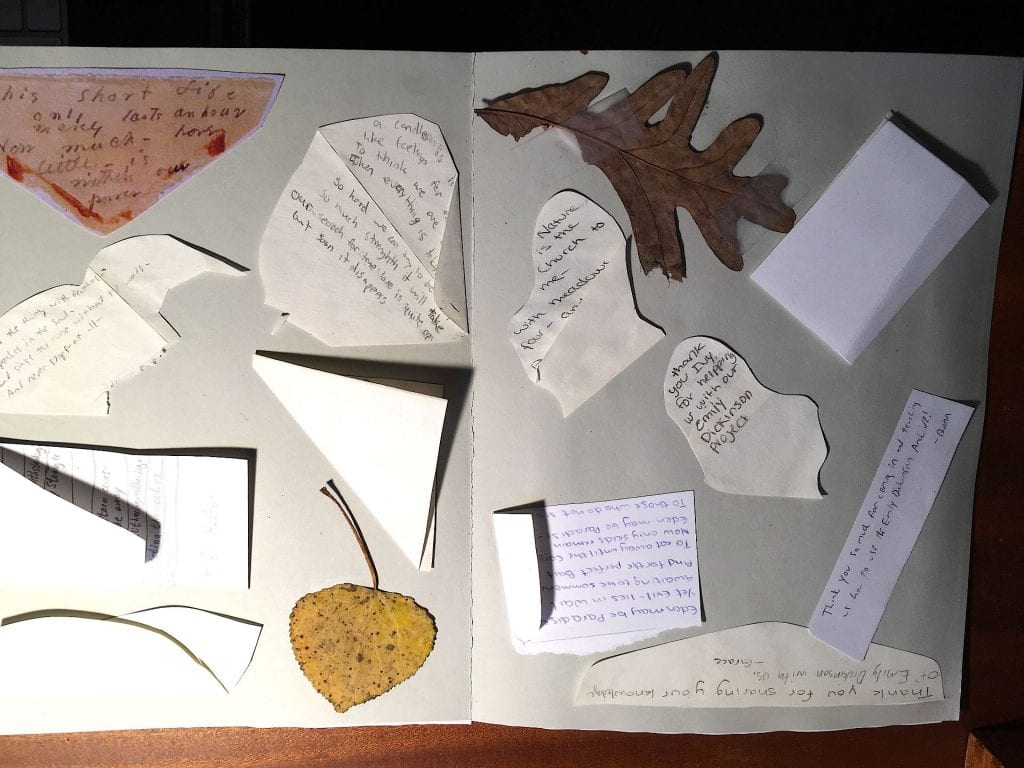

Another absolute revelation was engaging people to reflect on the weekly posts and the range and depth of passion for Dickinson this unearthed. From the amazing 7th graders at the Crossroads Academy in Lyme, New Hampshire, to a poet and translator living and working under life-threatening conditions in Iraq, a translator of Dickinson in Germany wrestling with diction choices, scholars and poets, friends and those who volunteered to reflect whom I had not even met—Dickinson continues to be a comfort and confidante to so many readers around the world and across time.

While the project didn’t manage to include every poem Franklin dated to 1862, it included a good many from “around” that year and some that don’t often get anthologized or discussed. But then, this project reinforced for me the folly of getting too hung up on dates and dating. Dickinson’s canon is a floating, morphing, wonderfully organic landscape that benefits from less strictures and determinations rather than more.

If we can let go of our need to “know,” to figure out the riddles or fill in the omitted center, or “understand” and, thus, pin down and lock in, then the poems have the leeway to work their magic on us more thoroughly. If I had to choose one major take-away from my year with Dickinson’s poetry, it would be:

ask questions rather than assert. Open up meanings rather than close them down. Bring a humility to our reading of the poetry

—a recommendation academics have a hard time embracing. But as the Crossroad students titled their thank you note to me:

“In Poetry is Possibility.”

Though fun, it was not always an easy year and I was sometimes daunted by how the research and writing on a weekly basis expanded to fit the time. In November, I presented the project to Martha Nell Smith’s class on Dickinson and Whitman at University of Maryland, and one of her students asked me: what gives you the energy to go on every week? Without thinking, I replied: Every week there is a surprise, often many surprises, which sometimes, for me—a Dickinson dilettante—rose to the level of a discovery.

A few other take-aways I would pass on:

The letters. There is some wonderful scholarship on Dickinson’s letters but they are not read frequently enough as aesthetic texts in their own right alongside the poetry. And perhaps they require a different, and new, methodology of textual reading. But read them we should be doing on a par with the poetry.

Speaker and Gender. I tried to honor Dickinson’s assertion in her letter to Higginson that her poetic speakers are “representative persons” rather than autobiographical, but then struggled with the presumption that her speakers are necessarily female or feminine or gendered at all! I loved the group of poems we found where Dickinson speaks not just in a masculine voice, but as a boy–a very particularly gendered and located voice. And her use of the plurals they and them for singular subjects or the arresting word, themself. I found myself often reaching for a non-gendered pronoun with which to refer to Dickinson’s speakers. This is an area that needs so much more work and innovative thought.

The World. Finally, the extent and richness of the world Dickinson occupied and evoked. Reading in the Springfield Republican for July about the discovery of the Swift-Tuttle comet, I wondered if I could find poems in Dickinson's canon that might touch on that event and was amazed to find a whole cluster of poems on Astronomy. Or the cluster of bloody poems on what fellow poet John Greenleaf Whittier called “the battle autumn of 1862.” We are still discovering the many ways that Dickinson engaged with her world and turned it into poetry.

But this is not the end. Or rather, as Peter Schumann, founder of Bread and Puppet Theater and a big fan of Dickinson, implies in his calendar for December: in ending are beginnings. We continue to send out the blog again in coming years, so if you have missed any posts, you will be able to catch up.

It has been an honor to share this project with you. Profoundest thanks to my students who worked to make this dream a reality, to my web designer Harriette Yahr and other tech wizards who lent their expertise, to my family who put up with my incessant monologues on things Dickinson, and to all the users, participants and fans who dared to “see a soul at the White Heat.”

Bio: Ivy Schweitzer is the creator and editor of White Heat.

Sources

Overview

Folsom, L. Edwin. “‘The Souls That Snow’: Winter in the Poetry of Emily Dickinson.” American Literature 47. 3 (Nov., 1975): 361-376, 376.

History

Atlantic Monthly, December 1862

Harper's Monthly, December 1862

Springfield Republican, December 27, 1862

Biography

Emerson, Ralph Waldo. Nature. Complete Works. RWE.org.

Patterson, Rebecca. Emily Dickinson’s Imagery. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1979, 182-83, 185.