On Choosing the Poems

As mentioned in the post for this week exploring the relationship of Emily Dickinson and Susan Dickinson, her sister-in-law and life-long correspondent, we have chosen poems that scholar Judith Farr includes in what she calls the “Sue cycle.” These are a series of “poems for and about a beloved and inaccessible woman,” which, Farr argues, are the result of “the narrative of Sue” she extracts from letters, biographies and poetry from the years 1858-1863 related to the Dickinson-Sue relationship. This narrative, Farr notes:

As mentioned in the post for this week exploring the relationship of Emily Dickinson and Susan Dickinson, her sister-in-law and life-long correspondent, we have chosen poems that scholar Judith Farr includes in what she calls the “Sue cycle.” These are a series of “poems for and about a beloved and inaccessible woman,” which, Farr argues, are the result of “the narrative of Sue” she extracts from letters, biographies and poetry from the years 1858-1863 related to the Dickinson-Sue relationship. This narrative, Farr notes:

cost Dickinson a great deal. It also gave her much: an experience of privation and sublimation that become one of her chief poetic themes.

Basically, Farr finds that in the 1850’s, Dickinson developed a grand passion for Susan, which Susan did not always or fully reciprocate, and which had cooled by 1861 after Susan married Dickinson’s brother Austin, moved next door to the Evergreens, began having children and building a busy and ambitious social life for herself. Also around this time, as other scholars confirm, Dickinson became focused on a male figure she calls “Master,” whose identity is unclear and whose significance to the poet we explored in an earlier post. As Farr explains,

Emily’s love for Sue is important, because it helps to explain consistent images and tropes in her art … and resulted in a body of poems and letters that is as eloquent and complex as any written to “Master.”

But in her revealing reconsideration of Sue’s role in Dickinson’s life and art, Martha Nell Smith argues that scholars have given far too much attention to “Master,” an unidentified figure who was the addressee of three letters and several poems, and not enough to Sue, who received hundreds of notes, letters and poems.

Farr also speculates that “As Sue’s character and personality became clearer to her over the years, Dickinson tried to become her opposite:” She explains:

If Sue were given to frivolity, snobbery, and ruthlessness, Dickinson became increasingly gentle and private. While Sue grew into a proud “cosmopolite,” Emily became the intimate of birds, plants, and children. As Sue became more and more busy “with scintillation,” Emily Dickinson busied herself with thought. … Nevertheless, while (as Dickinson said) the tie between them became very “fine,” it was “a Hair” that never dissolved.

Farr identifies a “cult of fond sentimentality among Victorian girls” tinged with “an ambiguous eroticism,” in which she reads the poems in the “Sue cycle.” This cult is exemplified by the photography of Lady Hawarden, often of her daughters as pictured here, with its soft-focus and filmy homoeroticism.

Farr finds this cult draws on works like Lord Alfred Tennyson’s Maud (1855), on a courtly tradition that associated women with birds and flowers, and on the sensuous imagery of the Biblical “Song of Solomon.”

In this vein, Dickinson came to associate Sue with Cleopatra from Shakespeare’s play, Antony and Cleopatra, with his sonnet sequence, which was addressed to both a “dark lady” and a young man, with eastern and oriental imagery of exoticism and luminous pearls (that slip through her fingers), as well as dangerous volcanoes — her nickname for Sue was “Vesuvius.” Sue also became associated with heaven and the imagination, prison and deprivation. We have chosen poems this week that illustrate several of these patterns of imagery.

This week’s poems:

Going – to – Her! (F277B, J494)

Going – to – Her!

Happy – Letter! Tell Her –

Tell Her – the page I never

wrote!

Tell Her, I only said –

the Syntax –

And left the Verb

and the Pronoun – out!

Tell Her just how the

fingers – hurried –

Then – how they – stammered –

slow – slow –

And then – you wished

you had eyes – in your

pages –

So you could see – what moved –

them – so –

Tell Her – it was’nt

a practised Writer –

You guessed –

From the way the sen –

tence – toiled –

You could hear the

Boddice – tug – behind you –

As if it held but the

might of a Child!

You almost pitied – it –

you – it worked so –

Tell Her – No – you may

quibble – there –

For it would split Her

Heart – to know it –

And then – you and I –

were silenter!

Tell Her – Day – finished –

before we – finished –

And the old Clock

kept neighing – “Day”!

And you – got sleepy –

And begged to be ended –

What could – it hinder

so – to say?

Tell Her – just how she

sealed – you – Cautious!

But – if she ask “where you are hid” – until the

evening –

Ah! Be bashful!

Gesture Coquette –

And shake your Head!

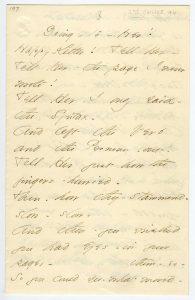

Link to EDA manuscript: "Originally in Amherst Manuscript # 197. Courtesy of Amherst College, Amherst, MA. First published in Poems (1891), 94-95, as three eight-line stanzas from F277C, 'Going to him! Happy letter!'”

This poem from 1862 exists in three versions: “Going – to – her!” “Going to him!” and “Going to them!” and illustrates Dickinson’s ability to adapt her emotional effusions across genders and types of relations. The speaker of the poem says that she has “left the Verb and the Pronouns – out,” but, in fact, Dickinson has put a proliferation of pronouns in!

Farr includes this poem in the Sue cycle, where it illustrates the speaker’s flirtatious elation tinged by trepidation in imagining her letter “going” to a female correspondent, perhaps across the hedges to the Evergreens and Sue. It is unclear whether Dickinson sent this poem to Sue or perhaps sent it as a draft. Franklin notes,

The earlier of the surviving manuscripts, from about early 1862, is on embossed notepaper and signed “Emily,” but not addressed or folded (A 197). It was ED’s record for the poem, the working draft of which she destroyed.

Franklin continues:

About later summer 1862, ED made another fair copy (A 689), apparently from the earlier one. The later copy, on embossed notepaper, was signed “Emily”’ and has been folded. Although prepared as if for a recipient, the manuscript remained among ED’s own papers. It was not sent to Samuel Bowles.

This is the version with the male pronouns. Another “lost manuscript, sent to Louise and Frances Norcross, was described by Mable Todd;” this one uses the plural pronoun.

What we might note about this poem are the thematic ellipses, the absences, what is left out. The speaker commands the letter she is writing to tell its recipient about “the page I never wrote!” What has been held back or omitted? What cannot or will not be said? And why then tell about it ? Many scholars speculate that Dickinson wrote to Sue in a coded language that could be read by Austin and others who carried letters for her and not be deciphered. But here the speaker refers to the omitted page as, in some way, the most precious and important part of the communication.

Each stanza ends on a moment of intensity. In the first stanza, the speaker’s surmise of the letter’s wish that it “had eyes – in your pages” so it could see the emotion that moved the stammering fingers of the writer, suggests feelings unutterably deep. In the second stanza, the speaker urges the letter to tell how the writer’s heart pounded “as if it held but the might of a Child!” But then fears this disclosure would break the recipient’s heart. In the last stanza, the speaker enjoins the letter not to tell where it was hidden until it could be sent–rendering the imagined place (a heaving bosom?) exquisitely alluring.

Sources

Farr, Judith. The Passion of Emily Dickinson. Harvard University Press, 2004: 100-177.

Dickinson, Emily. The Poems of Emily Dickinson: Variorum Edition. Ed. R. W. Franklin. Cambridge: the Belknap Press of Harvard University, 1998, 294-96.

Her smile was shaped like other smiles (F335A, J514)

Her smile was shaped like other smiles –

The Dimples ran along –

And still it hurt you, as some Bird

Did hoist herself, to sing,

Then recollect a Ball, she got –

And hold opon the Twig, –

Convulsive, while the Music

crashed –

Like Beads – among the Bog –

A happy lip – breaks sudden –

It does’nt state you how

It contemplated – smiling –

Just consummated – now –

But this one, wears it’s merriment

So patient – like a pain –

Fresh gilded – to elude the eyes

Unqualified, to scan –

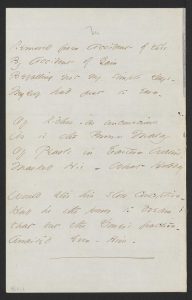

EDA manuscript: "Originally in Packet XIV, Mixed Fasciles, ca. 1860-1862, Fascicle 12, Houghton Library – (77b, c). First published in Unpublished Poems (1935), 123, in part, as three quatrains. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA."

As part of the “Sue cycle,” this poem details the destructive power of the beloved woman. The violence is disguised, however, in seemingly familiar smiles and dimples, a situation mirrored by the nearly perfect form of common meter (alternating iambic tetrameter and trimeter) but with wildly erratic rhymes. There are no rhymes, even slant one, in the first stanza, suggesting, perhaps, how out of sync the speaker feels with her female beloved.

Also notable here is the reversal of the bird imagery. Farr examines early poems in which Dickinson uses bird imagery to describe Sue and the friendship she wants to have with her. For example, in the early poem,“One Sister have I in our house” (F5A, J14) from 1858, which we discussed earlier in this week’s post, Dickinson describes Sue

as a bird her nest,

Builded our heart among.She did not sing as we did –

It was a different tune–

Herself to her a music

As Bumble bee of June.

Sue is a bird of a different stripe, singing a singular, even self-referential music, like the bumblebee, which Dickinson often associates with sexuality and pain (the sting).

By contrast, in “Her smile was shaped like other smiles,” the speaker is the bird, ready to sing her praises of the beloved’s smile, when it “recollect[s] a Ball, she got–,” that is, remembers that she was shot by a hunter’s gun, and grabs the twig “convulsive” while the music of her song and the hope of her bliss crash around her head. This image recalls the first line of the Third Master document discussed in a previous post:

If you saw a bullet hit a Bird – and he told you he was’nt shot – you might weep at his courtesy, but you would certainly doubt his word.

This wounding imagery connects the speaker’s feelings for the beloved woman and the Master, though Farr argues that the renunciation each elicits from the poet is different. In the case of Sue, their passion “is forbidden as a type,” while the passion for the Master is forbidden because he is already taken, and union is postponed to the afterlife. The presence of the bird connects both forms of renunciation with singing and poetry.

Sources

Farr, Judith. The Passion of Emily Dickinson. Harvard University Press, 2004, 160.

Removed from accident of loss (F417A, J424)

Removed from Accident of Loss

By Accident of Gain

Befalling not my simple Days –

Myself had just to earn –

Of Riches – as unconscious

As is the Brown Malay

Of Pearls in Eastern Waters –

Marked His – What Holiday

Would stir his slow conception –

Had he the power to dream

That but the Dower’s fraction –

Awaited even – Him –

EDA manuscript: "Originally in Packet X, Mixed Fascicles, ca. 1858-1862. Fascicle 14. First published in Unpublished Poems (1935), 73. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA."

One of the governing structures of the relation with Sue and with her literary avatar is triangulation, based on several biographical triangles: Dickinson-Sue-Austin, Dickinson-Sue-Samuel Bowles, and perhaps Dickinson-Kate Anthon-Sue. Anthon was a young widow and school friend of Sue’s whom Emily met in 1860 at Sue’s house and about whom she developed warm and even passionate feelings.

We have seen this triangulation before in “The Malay – took the Pearl” (F451A, J425), discussed in an earlier post on White. Farr places that poem and “Removed from Accident of Loss” in what she calls “the pearl sequence” and links them to Dickinson’s network of imagery of

riches/poverty, intelligence/dullness, and the eastern sea – her complex conceit embracing passion, imagination, and eternal life.

Farr paraphrases the poem as a scenario much like “The Malay took the Pearl,” with Austin as the masculine “dark” force “unconscious” of his wealth and acting as the rival of the “simple” speaker for the affections of Sue/the pearl. Still, the poem seems determined not to give up a meaning readily. Is the speaker relieved to be “removed” from the loss? Or does the emphasis fall on the repeated word, “accident,” which suggests the beloved object’s unpredictability? Some economy of loss and gain, accident and earnings, riches and holiday from work, dreams and dowers mark the speaker’s response to what she cannot have.

Sources

Farr, Judith. The Passion of Emily Dickinson. Harvard University Press, 2004, 150-51.

Your – Riches – taught me – poverty! (F418A, J299)

Your – Riches – taught me – poverty!

Myself, a “Millionaire”

In little – wealths – as Girls can boast –

Till broad as “Buenos Ayre” –

You drifted your Dominions –

A Different – Peru –

And I esteemed – all – poverty –

For Life’s Estate – with you!

Of “Mines” – I little know – myself –

But just the names – of Gems –

The Colors – of the Commonest –

And scarce of Diadems –

So much – that did I meet the Queen –

Her glory – I should know –

But this – must be a different wealth –

To miss it – beggars – so!

I’m sure ’tis “India” – all day –

To those who look on you –

Without a stint – without a blame –

Might I – but be the Jew!

I know it is “Golconda” –

Beyond my power to dream –

To have a smile – for mine – each day –

How better – than a Gem!

At least – it solaces – to know –

That there exists – a Gold –

Altho’ I prove it, just in time –

It’s distance – to behold!

It’s far – far – Treasure – to surmise –

And estimate – the Pearl –

That slipped – my simple fingers – thro’

While yet – a Girl – at school!

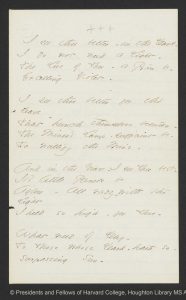

EDA manuscript: "Originally a note and poem signed “Emily” to Susan Huntington Dickinson, [early 1862] Ink; 3 1/3p. MS Am 1118.5 (B44), Fascicle 14. First published by Higginson, Atlantic Monthly, 68 (October 1891), 446, from the copy sent to him (B); Poems (1891), 91-92, from the fascicle (C). Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA."

This poem was included in a note Dickinson sent to Sue next door at the Evergreens in 1862, which read simply:

Dear Sue–You see I remember–Emily.

To emphasize its status as a letter directed to a particular person, Dickinson also wrote above the poem, “Dear Sue.” But she also sent a copy to Thomas Wentworth Higginson, whom she was soon to ask to become her “preceptor,” some think, as a replacement for Sue. She also copied the poem into Fascicle 14 after the poem just discussed, “Removed from Accident of Loss” (F417A, J424).

This poem is both a farewell to Sue, who had recently become a mother and was making her place as the wife of one of Amherst’s most influential men, and an evocation of what Sue meant to the poet. Paula Bennett observes that it is

the only poem in which Dickinson ever felt totally free to express in direct and undisguised form the love she felt for this extraordinary and very much underrated woman.

It is part of the “pearl sequence,” although here the speaker admits letting the pearl slip through her fingers while she was a school girl, not as a result of losing a competition with a dusky male figure.

The poem uses ironic reversals: Sue, who had been poor, is now rich as Austin’s wife, but the “riches” of her allurements, compared to exotic, torrid places like “Buenos Ayre,” “Peru” (known for its silver mines), and “India,” also make the speaker feel impoverished or inadequate as a woman and suitor. Still, the speaker says she would give all she had, “For Life’s Estate with you–.” Sue is described not only in terms of wealth, especially the wealth of mines and diamonds, but as a Queen, with a diadem and a degree of royalty that in other poems Dickinson takes for herself as the sign of her maturity and independence. The “smile” in stanza 6 is the inverse of the deadly smile of “Her smile was shaped like other smiles” (F335a, J 514).

Judith Farr notes that Harper’s Monthly, Atlantic Monthly and Scribner’s had all run articles about diamond mining and cutting in South America and India at the time. The imagery of “mines” also puns on the notion of possession and in stanza 5 hints at the forbidden love. If the speaker could be “the Jew,” alluding to the stereotyped image of Jewish merchants who were often diamond traders, she could look at Sue without “blame.” This emotion is intensified in the next stanza through the reference to “Golconda,” a region in India known for its diamond production as well as a notorious fort and prison where the famous Koh-i–Noor diamond was once stored in the vaults, along with other diamonds.

Sources

Bennett, Paula. My Life, a Loaded Gun: Female Creativity and Feminist Poetics. Boston: Beacon Press, 1986, 53-55.

Farr, Judith. The Passion of Emily Dickinson. Harvard University Press, 2004, 140-42.

Leiter, Sharon. Critical Companion to Emily Dickinson: A Literary Reference to her Life and Work. New York: Facts on File, 2007, 234-35.

I see thee better – in the Dark – (F442, J611)

I see thee better – in the Dark –

I do not need a Light –

The Love of Thee – a Prism be –

Excelling Violet –

I see thee better for the

Years

That hunch themselves between –

The Miner’s Lamp – sufficient be –

To nullify the Mine –

And in the Grave – I see Thee best –

It’s little Panels be

A’glow – All ruddy – with the

Light

I held so high, for Thee –

EDA manuscript: "Originally in Packet XXXIV, Fascicle 21, ca. 1862. First published in The Single Hound (1914), 85, from the copy sent to Susan ([B]). Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA."

Dickinson sent a copy of this poem to Sue in 1862, which Sue’s daughter Martha included in The Single Hound, the collection of poems she published from her mother’s cache of poetry sent to her in letters. Another version, now lost, was sent to the Norcross cousins. It picks up the “mining” imagery of the previous poem, “Your – Riches – taught me – poverty!” (F418A, J299) but uses it to suggest burial and lovers meeting in the depths of the grave, which will be illumined by the light of their passion.

According to Judith Farr,

This conceit of burial and destruction after love’s explosion surely had some relation to [Dickinson’s] own life

and her increasing withdrawal, in particular, her refusal to see Samuel Bowles when he finally returned from his European travels. Farr continues, it is

apposite to the considerable number of her poems which imagine both beloveds–female and male–as entombed with her.

This poem is part of that cluster, as is “I see thee clearer for the grave” (F1695A, J1666), and associates the poems to and about Sue with poems to and about the Master.

Sources

Farr, Judith. The Passion of Emily Dickinson. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 1992, 215.

Like Eyes that looked on Wastes (F693A, J458)

Like Eyes that looked on Wastes –

Like Eyes that looked on Wastes –

Incredulous of Ought

But Blank – and steady Wilderness –

Diversified by Night –

Just Infinites of Nought –

As far as it could see –

So looked the face I looked opon –

So looked itself – on Me –

I offered it no Help –

Because the Cause was Mine –

The Misery a Compact

As hopeless – as divine –

Neither – would be absolved –

Neither would be a Queen

Without the Other – Therefore –

We perish – tho’ We reign –

EDA manuscript: "Originally in Packet XL, Fascicle 32, ca. 1862 [though Franklin dates it to the second half of 1863]. Houghton Library – (127c). First published in Bolts of Melody (1945), 111, from a transcript of A (a tr515). Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA."

Judith Farr places this poem at “the crux of the Sue story.” It recounts the effects of a face-to-face encounter, and may help to explain why Dickinson had begun to avoid them. In other poems about the lost or absent lover, Dickinson longs for a mutual ocular feeding that feels sacramental, as in “One Year ago–Jots what” (F 301A, J 296):

Such anniversary shall be –

Sometimes – not often – in Eternity –

When +farther Parted, than the + sharper

common Wo –

Look – feed opon each other’s

faces – so –

In doubtful meal, if it be possible

Their Banquet’s +real – +True

In “Like Eyes that looked on Wastes” we get the opposite scenario: looking into another’s face and seeing a nothingness that is rendered in grimly multiplying and expanding terms: Wastes, Ought, Wilderness, Infinites of Nought. This is an existential landscape so “blank” that it can be “diversified by Night,” itself already a steady, unbroken darkness. We should also note that this bleakness is further distanced by simile: the eyes looking on wastes serve as a figure for how the faces looked to each other and to themselves. For this poem also belongs to the category of “split self” poems.

This scenario, according to Farr, resembles other literary examples of passionate or narcissistic looking; the metaphysical poet John Donne’s lovers in “The Ecstasy” with their “eyebeams twisted,” for example. More specifically, she notes its symbology for lesbian attachment:

Their reciprocal gaze describes that mirror by which many nineteenth-century painters portrayed Sapphic love.

The mirror is an apt image for this extraordinary poem. Gone is the power differential and struggle between the speaker and her beloved. Rather, they are both Queens manqué, joined by an equally felt “Misery” in “a Compact/ As hopeless – as divine.”

Sources

Farr, Judith. The Passion of Emily Dickinson. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 1992, 160-63.

Sources

Farr, Judith. The Passion of Emily Dickinson. Harvard University Press, 2004, especially pp. 100-177.

Smith, Martha Nell. Rowing in Eden: Rereading Emily Dickinson. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1992.