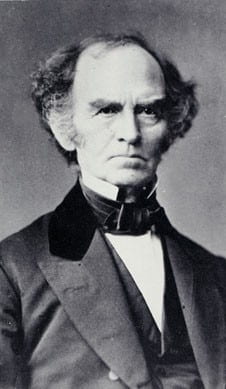

Edward Dickinson

“He buys me many Books – but begs me not to read them”

Though Edward Dickinson may have bought his daughter Emily Dickinson many books, his role in her life was more complicated than that of a fatherly didact. One such book he purchased was Letters on Practical Subjects to a Daughter by William B. Sprague, a sort of etiquette manual of orderly conduct for women. At the very least, this gift shows some fatherly desire to control and to rein in his daughter's intellect. Edward also bought her Dr. Gregory’s A Father’s Legacy to His Daughter, another advice manual. Writing to Higginson, Emily Dickinson comments that her father “buys me many Books” but suggests that he knows little about her and how she occupied her time, because he is “too busy with his Briefs” (L261). Even when he was absent on business trips, the books he gave to his daughter were an attempt to maintain control over her conduct and shape what he might have regarded as her flagging sense of social decorum.

That Edward Dickinson begged his daughter not to read books, fearing they would “joggle the mind,” makes his gifts all the more curious. He certainly wasn’t afraid that she might read and internalize those instructive manuals on proper female conduct. He must have feared the effect other, perhaps literary and intellectual, books had on her—a father afraid that his daughter’s ever-growing intellect would break the belt he had strapped around her life.

This week’s post explores the influence Edward Dickinson had on Emily Dickinson’s life and writing. Having grown up in a family facing financial trouble, Edward Dickinson governed his own household with a firm hand, kept a tight domestic economy, and imposed his values on his family members. While Emily Dickinson respected her father greatly, and tended to obey the rules he set for her, she kept her poetry well out of his reach. She only mentioned him directly in one poem, “Where bells no more affright the morn” (F114), which is based in fact: he would literally wake his children with a bell at an early hour. Thus, Edward is largely absent from her poetry. Following the lead of Dickinson scholars, however, we’ve located him in other places: in her legal vocabulary, in her metaphors of domestic control, and in her notions of power.

“No more kid-glove policy”

NATIONAL HISTORY

Hampshire Gazette, April 15, responds to the battle of Shiloh on April 6-7th"

“The best contested and most sanguinary battle that ever took place on this continent, occurred on Sunday and Monday of last week. The rebel forces, under Gens. Beauregard and S.E. Johnston, advanced from their fortified position at Corinth, evidently with the intention of defeating our army by piecemeal, and attacked that portion of it stationed at Pittsburg Landing in Tennessee. It was a complete surprise and during the first day our forces were defeated, and had it not been for the opportune arrival of reinforcements, the union army would have met with a most fatal reverse.”

Springfield Republican, April 12, “Civil War in Cipher,” p. 4:

“A Cipher Despatch from Beauregard.—We have been shown a dispatch or message, in cipher, from Beauregard to some confederate in Washington, which, in addition to the ingenuity which characterizes the cipher, contains intrinsic evidence both as to its origin and the desperate means proposed by the rebel general for getting possession of the capital. It seems certain that arson and assassination were component parts of the chivalry of which we heard so much a year or so ago, and perhaps the publication of such a dispatch as this may modify the tender sensibility of those who adhere to the kid-glove policy in dealing with rebels who themselves stickle at nothing in prosecuting their traitorous schemes.”

Springfield Republican, April 12th, p. 5, Proclamation by the President:

“By the President of the United States of America—a Proclamation: It has pleased Almighty God to vouchsafe signal victories to the land and naval forces engaged in suppressing an internal rebellion, and at the same time to avert from our country the dangers of foreign intervention and invasion. It is therefore recommended to the people of the United States, that at their next weekly assemblages in their accustomed places of public worship, which shall occur after the notice of this proclamation shall have been received, they especially acknowledge and render thanks to our Heavenly Father for these inestimable blessings.”

Hampshire Gazette, April 15th: “Edward Dickinson in the Public Eye”

“Presentation of Cannon.—The ceremony of presenting a six-pound brass cannon captured from the rebels at the battle of Newbern, by the 21st Mass. regiment, to the trustees of Amherst College, took place at Amherst yesterday. The occasion called together about two thousand people, who gathered in front of the college chapel building, where the ceremonies were held. The cannon is a beautiful piece. It bears the stamp of ‘U.S.,’ and is believed to be one of the pieces captured from the federal army at Bull Run. … Hon. Edward Dickinson presided and introduced the speakers.”

Atlantic Monthly, April 15, “Letter to a Young Contributor” by Thomas Wentworth Higginson

My dear young gentleman or young lady,—for many are the Cecil Dreemes of literature who superscribe their offered manuscripts with very masculine names in very feminine handwriting,—it seems wrong not to meet your accumulated and urgent epistles with one comprehensive reply, thus condensing many private letters into a printed one. And so large a proportion of “Atlantic” readers either might, would, could, or should be “Atlantic” contributors also, that this epistle will be sure of perusal, though Mrs. Stowe remain uncut and the Autocrat go for an hour without readers.

How few men in all the pride of culture can emulate the easy grace of a bright woman’s letter!

Yet, if our life be immortal, this temporary distinction is of little moment, and we may learn humility, without learning despair, from earth’s evanescent glories. Who cannot bear a few disappointments, if the vista be so wide that the mute inglorious Miltons of this sphere may in some other sing their Paradise as Found? War or peace, fame or forgetfulness, can bring no real injury to one who has formed the fixed purpose to live nobly day by day.

“His Heart was pure and terrible and I think no other like it exists”

The eldest of nine children, Edward Dickinson was born in Amherst, Massachusetts in 1803 to an established family. His parents, Samuel Fowler Dickinson and Lucretia Gunn Dickinson, valued education and, despite financial difficulties, sent their son to Amherst Academy, Yale University, and Northampton Law School.

Equipped with a first-rate education and a traditional set of values, Edward Dickinson launched a successful career in law, was elected as a Representative to the General Court of Massachusetts in 1838, to the National Whig Convention in Baltimore in 1852, and to the Congress of the United States as a Representative from the Tenth Massachusetts District in that same year. His successful career buoyed his stature in the Amherst community, and he governed the Dickinson household with a authoritative hand commensurate with his status as a prominent legal and political figure.

Equipped with a first-rate education and a traditional set of values, Edward Dickinson launched a successful career in law, was elected as a Representative to the General Court of Massachusetts in 1838, to the National Whig Convention in Baltimore in 1852, and to the Congress of the United States as a Representative from the Tenth Massachusetts District in that same year. His successful career buoyed his stature in the Amherst community, and he governed the Dickinson household with a authoritative hand commensurate with his status as a prominent legal and political figure.

Even his personal life was touched by his ambitious resolve; in a letter to Emily Norcross, whom he would later marry, he wrote,

My life must be a life of business, of labor and application to the study of my profession.

His obsessive commitment to his career set in motion a precarious and, at times, distant relationship with his family, especially his eldest daughter, Emily Dickinson. As a politician, he was eager to bring a railroad to Amherst, an accomplishment that was met with

great rejoicing through this town and the neighboring [one],

according to Dickinson in a letter to her brother Austin (L72). She admired her father's success, commenting a bit wryly later in the correspondence that

Father is really sober from excessive satisfaction, and bears his honors with a most becoming air.

Though Dickinson clearly thought highly of her father, his conventional values and imposing authority strained their relationship. Writing to Austin, who was away at school, she expressed regretfully that she and her family

don’t have many jokes tho’ now, it is pretty much all sobriety, and we do not have much poetry, father having made up his mind that it’s pretty much all real life. … Father’s real life and mine sometimes come into collision, but as yet, escape unhurt! (L65).

Similar sentiments emerge in other correspondences. To Higginson, Dickinson wrote,

and Father, too busy with his Briefs – to notice what we do – He buys me many Books – but begs me not to read them – because he fears they joggle the mind (L261).

Their relationship was one of contrasts: Edward Dickinson was supportive of his daughter's education yet wary of its effects, overbearing in his authority yet distant and, as Emily withdrew from religious observance, Edward underwent a religious conversion in the revival in Amherst in 1850. Her tone about him is routinely marked by a regretful distance. In a letter to Joseph Lyman, she wrote:

My father seems to me often the oldest and the oddest sort of a foreigner. Sometimes I say something and he stares in a curious sort of bewilderment though I speak a thought quite as old as his daughter… And so it is, for in the morning I hear his voice and methinks it comes from afar & has a sea tone & there is a hum of hoarseness about [it] & a suggestion of remoteness as far as the isle of Juan Fernandez.

Richard Sewall, Dickinson's biographer, describes their relationship as

compounded of many elements incompatible with fear. It developed early into an amused tolerance, a touch of condescension arising from an entirely justified sense of intellectual superiority, a tender devotion that made her delight in serving him in many ways, and later on into a deep, pervasive pity for his lonely and austere life.

Edward Dickinson died in Boston on June 16, 1874 shortly after speaking in the General Court, where he reportedly felt ill. Though Dickinson occasionally commented on her relationship with her father while he was alive, her posthumous remarks are keenest. In a letter to Higginson in 1874, a month after Edward's passing, she reflects on the memories she has of her father (L418):

The last Afternoon that my Father lived, though with no premonition – I preferred to be with him, and invented an absence for Mother, Vinnie being asleep. He seemed peculiarly pleased as I oftenest stayed with myself, and remarked as the Afternoon withdrew, he “would like it to not end.”

His pleasure almost embarrassed me and my Brother coming-I suggested they walk. Next morning I woke him for the train – and saw him no more.

His Heart was pure and terrible and I think no other like it exists.

I am glad there is Immortality-but would have tested it myself-before entrusting him.

Mr Bowles was with us–With that exception I saw none. I have wished for you, since my Father died, and had you an Hour unengrossed, it would be almost priceless. Thank you for each kindness.

My Brother and Sister thank you for remembering them.

Reflection

Hannah Matheson

Two Poems

SOTERIOLOGY

Salvation’s brutal logic. Our Father progenitor

of Munchausen by proxy: made us wrong

to be the one to fix broken. Fashioned

to fall. How’s that for self-

indulgence? His and mine,

I mean. Made in His image,

cheap facsimile that

I am, a mirror of ire. Anger is

unflattering. This is why we say

fear of God, and this is why

Sunday service finds me close-

fisted, fingernails carving red

crescents into my own palms,

but even if I gall I recognize

the architecture of a fine thing,

ornate scaffolding of psalms—

exquisite echolalia of call

and response, which is at least

an answer, even if it returns

in the sound of one’s own voice

whispering prayer, soothing

sleep along. What alternative

do I offer when, asked

a question, I can do nothing

but point to all my milk teeth

scattered on the floor?

LUST (II)

and my eyes, like the Sherry in the Glass, that the Guest leaves –Dickinson

For so long, Emily, my body as a scaffold of loss: self-

portraiture a composite of leavable parts. Anatomy

predicated on negative space—skeleton defined

by the emptiness filling around it. My ribs so hungry,

bone stitches suturing air. So much nothing. So much

take it or leave it, as they wished. I did not want to tell you

about what I allowed this frame to weather.

My labia scoured by a whiskered mouth. Rawed down

until I swelled, bleeding rose—red spattering of cells

in my underwear. I took it like a moth pinned

to corkboard, wingspread, still. Another time,

a different pair of hands, also hungry… I yearned

my pelvis away from his looming need. Battering

ram of his fingers breaching my borders, somehow

he sowed longing, somehow I wanted him

to want me, the truth is I did

go back, as if searching for the pummeling. What

did I think I could wrest from another night

in that dank room? As simple as a dog returning, wanting

to be un-kicked. I keep running from, running to

this exacting metronome but and of course the jolts

of these pulses are like everything else

a familiar rhythm—heartthrums, footfalls, the same

frat house couch spring

it hurt it hurt it hurts

bio: Hannah Matheson is a member of the class of 2018 at Dartmouth College and was an English major concentrating in Creative Writing. She studied poetry with Vievee Francis. She has edited for Mouth and The Stonefence Review, literary publications at Dartmouth, and sang in The Subtleties, an all-female a cappella group. .

Overview

Habegger, Alfred. My Wars are Laid away in Books. New York: Random House, 2001, 46.

History

Atlantic Monthly, April 15, 1862.

Hampshire Gazette, April 15, 1862.

Springfield Republican, April 12, 1862.

Biography

Dickinson, Emily. The Letters of Emily Dickinson. Eds. Thomas Johnson and Theodora Ward. 3 vols. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1958.

Martin, Wendy, ed. All Things Dickinson: an Encyclopedia of Emily Dickinson’s World. Greenwood, 2014.

Sewall, Richard B. The Life of Emily Dickinson. Cambridge: Harvard Univesity Press, 1974, 61.

Interesting. It’s my sense that her father haunts many of Dickinson’s poems, especially after his death. (“While we were fearing it, it came–“, “How soft his Prison is”, “From his slim Palace in the Dust,” etc.) I also suspect Dickinson is often posing, especially in her letters to Higginson. She presents herself as unappreciated and neglected by her parents, though this doesn’t hold up to scrutiny of the family dynamics. Rather than being afraid of her father, my sense is that Dickinson had him wrapped around her little finger.