On Choosing the Poems

As discussed in this week’s post, we are following the lead of Higginson and Thoreau, who both wrote about health in the June issue of the Atlantic Monthly. Thus, this week’s poems focus on health and illness–but mostly illness–in Dickinson’s poetry. As James Guthrie points out, in 1862 Dickinson was “suffering from a chronic optical illness” that corresponded with an “intensified creativity.” Illness and literary inspiration may have been linked in Dickinson’s mind, especially since she started writing to her “preceptor,” Thomas Wentworth Higginson, at this time, making frequent reference to illness, both literal and metaphorical in relation to her poetry.

April, May, and June mark the return of the sun after long New England winters. Guthrie argues that a

corresponding tension is set up in which sun and summer entice the poet while threatening her simultaneously with physical or imaginative collapse, generating a dialectic of desire and deferred gratification

that play out in her poetry. In Guthrie’s mind, poetry functioned for Dickinson as an “alternative mode of perception” when her vision was at its darkest. That is, poetry was Dickinson’s panacea for her own illness; another way to see when seeing became difficult.

Sources

Guthrie, James R. Emily Dickinson’s Vision: Illness and Identity in Her Poetry. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1998, 2.

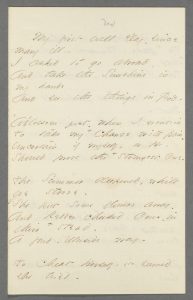

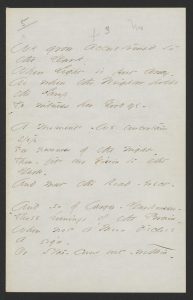

My first well day since many ill (F288B, J574)

My first well Day – since

many ill –

I asked to go abroad,

And take the Sunshine in

my hands

And see the things in Pod –

A'blossom just – when I went in

To take my +Chance with pain –

Uncertain if myself, or He,

Should prove the +strongest One.

The Summer deepened, while

we strove –

She put some flowers away –

And Redder cheeked Ones – in

their +stead –

A fond – illusive way –

To Cheat Herself, it seemed

she tried –

As if before a Child

To +fade – Tomorrow – Rainbows

+held

The Sepulchre, could hide.

She dealt +a fashion to the

Nut –

She tied the Hoods to Seeds –

She dropped bright scraps

of Tint, about –

And left Brazilian Threads

On every shoulder + that she met –

Then both her Hands of Haze

Put up – to +hide her

parting Grace

From our +unfitted eyes –

My loss, by sickness – Was it

Loss?

Or that +Etherial Gain

One earns by measuring the

Grave –

Then – measuring the Sun –

+[Chance] Risk +[Strongest] supplest • lithest • stoutest

+ [stead] place + [fade] die

+ [held] thrust + [a] the + [that she met] she could reach

+ [hide] hold + [unfitted] unfurnished

+ [Etherial Gain One earns] seraphic gain One gets

EDA manuscript: Originally in Amherst Manuscript # 685, Emily Dickinson letter to Samuel Bowles – asc:11414 – p. 1. Courtesy of Amherst College, Amherst, MA. First published in Letters (1894), 210, in the letter to Bowles (A); Unpublished Poems (1935), 43-44, with the alternatives not adopted, from the fascicle copy (B).

Dickinson incorporated the final stanza of this poem into a letter to her friend, Samuel Bowles, who had just returned from a European trip he took for his health, sometime around mid-November 1862 (L275). She copied the entire poem into Fascicle 28 around Spring 1862 in the 17th position, after a poem entitled “The Test of Love – is Death” (F541, J573).

The poem tells of a speaker who took to her bed in illness during the spring, when the world was just “A’blossom,” and is only able to get up and go outside in the late summer when the fall colors are beginning and a personified Summer touches the world with “Hands of haze … to hide her parting Grace.” Thus, the speaker loses the summer, which is also known to “Cheat Herself” by taking some flowers away but putting “Redder cheeked Ones – in their stead.” Those ruddy cheeks could betoken health, but the rest of this stanza alludes to the death of a child, who is comforted with a tale about soon seeing rainbows.

The speaker’s account of her illness is revealing. She describes it as a contest of strength that she ostensibly wins when she finally emerges from the sickroom: “when I went in/ To take my Chance with pain–/ Uncertain if myself, or He, / Should prove the strongest (variants: supplest, lithest, stoutest) One.” But the last stanza calls this conclusion into question. Although she lost the summer, her brush with illness, pain and death (“grave”) gave her a truer index by which to measure and appreciate life (“the sun”). As Susan Kornfeld comments:

The appreciation of a thing by awareness of its opposite is a theme in several Dickinson poems.

Sources

Kornfeld, Susan. “the prowling bee.” 10 July 2012.

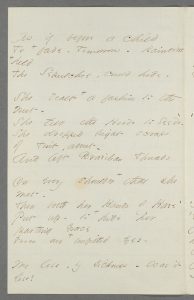

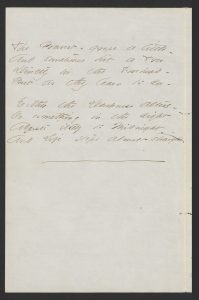

Before I got my eye put out (F336A, J327)

Before I got my eye

put out

I liked as well to see –

As other Creatures, that

have Eyes

And know no other way –

But were it told to

me – today –

That I might have the

sky

For mine – I tell you

that my Heart

Would split, for size of

me –

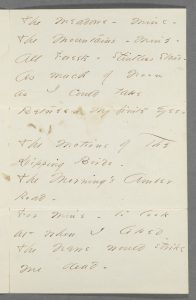

The meadows – mine –

The Mountains – mine –

All Forests – Stintless Stars –

As much of Noon

as I could take

Between my finite eyes –

The Motions of The

Dipping Birds –

The Morning's Amber

Road –

For mine – to look

at when I liked –

The News would strike

me dead –

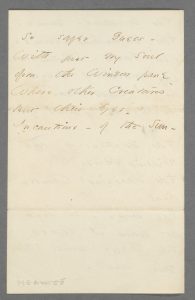

So safer Guess –

With just my soul

opon the Window pane –

Where other Creatures

put their eyes –

Incautious – of the Sun –

EDA Manuscript: Originally in A.MS. (unsigned) poem; [n.p., ca. 1862 Aug.]. 1s. (3p.) MS Am 1118.1 (14). Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. First published in Poems (1891), 60-61, as five quatrains, from the fascicle copy (B), with the alternative not adopted.

Perhaps Dickinson's most direct reference to the failing of her eyes, “Before I got my eye put out” details a speaker’s appreciation for observing nature, even as her vision falters. That appreciation quickly becomes a desire to consume or possess nature: “But were it told to / me – today – / That I might have the sky / For mine.” A literal impossibility, having the sky for oneself reads as a metaphor for glimpsing heaven prematurely. Though she previously acted as “other Creatures,” looking with her eyes, the speaker concludes in the final stanza to look differently—without her eyes: “So safer Guess – / With just my soul / opon the Window pane.” In fact, this newfound method of looking transcends entirely her “finite eyes.”

James Guthrie offers first a literal interpretation of the poem: Dickinson feels that getting her eye put out is punishment for not following the doctor’s orders. On a semantic level, however, Dickinson’s eye is “put out,” indicating that the source of her affliction is external:

Her description of scenes she would look upon, were she to regain full use of her eyes, is so rapturous that we may infer her transgression had been to admire the visible world excessively.

That external force might be God, punishing her for consuming the beauty of nature too eagerly, and likening earth to heaven, thus glimpsing heaven before her time. The repetition of “mine” in the third stanza along with the lines, “As much of Noon / as I could take / Between my finite eyes,” all gesture at consumptive greed. That the “News would strike [her] dead” ties her consumption to the transcendence of death.

Richard Sewall connects “Before I got my eye put out” to Higginson, noting that Dickinson included it in a letter to him in August, asking about the new poems she enclosed, “Are these more orderly?” Though this is not an orderly poem, Dickinson’s characterization of nature would have surpassed Higginson’s orderly treatment of it; as Guthrie comments, his writing did not

come close to the overwhelming, even mortal, experience when, for the supremely sensitive soul, mere observation becomes possession and man [sic] and nature are one.

Sources

Guthrie, James R. Emily Dickinson's Vision: Illness and Identity in Her Poetry. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1998, 15-16.

Sewall, Richard. The Life of Emily Dickinson. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1980, 558-59.

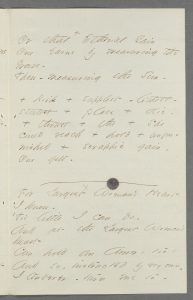

The Soul has Bandaged moments (F360A, J512)

The Soul has Bandaged moments –

When too appalled to stir –

She feels some ghastly Fright

come up

And stop to look at her –

Salute her, with long fingers –

Caress her freezing hair –

Sip, Goblin, from the very lips

The Lover – hovered – o'er –

Unworthy, that a thought so

mean

Accost a Theme – so – fair –

The soul has moments of escape –

When bursting all the doors –

She dances like a Bomb, abroad,

And swings opon the Hours,

As do the Bee – delirious borne –

Long Dungeoned from his Rose –

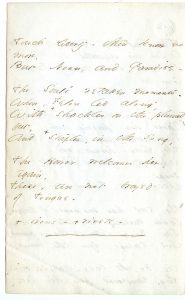

Touch Liberty – then know no

more –

But Noone, and Paradise

The Soul's retaken moments –

When, Felon led along,

With +shackles on the plumed

feet,

And +staples, in the song,

The Horror welcomes her,

again,

These, are not brayed

of Tongue –

+irons +rivets

EDA manuscript: Originally in: Amherst – Amherst Manuscript #fascicle 85 – I dreaded that first robin, so – asc:17622 – p. 11. Courtesy of Amherst College, Amherst, MA. First published in Bingham, Ancestors' Brocades (1945), 331, lines 1-2; Bolts of Melody (1945), 244-45, as three stanzas of 10, 8, and 6 lines, with the alternative for line 22 adopted.

James Guthrie reads “The Soul has Bandaged moments” as an example of a creative arc through illness:

Denied the stimulus of perception, Dickinson’s burgeoning creativity, which was driving her in 1862 to write at the rate of a poem a day, might slow down, wither or even die.

This poem, for which Guthrie offers a literal paraphrase, represents a relief from the stagnancy of illness; it

quite possible chronicles one of the poet’s flights from her sickroom to the brilliant, yet fatal, refuge of the family flower garden.

Considering its style, Cynthia Wolff points to the poem’s “compression,” which conveys a “surrealistic ordeal.” Dickinson is able to capture intense, dark feelings in tight verses full of metaphor and personification—“Fright,” “Horror”—which are able to convey the complex external power of illness. Wolff continues:

The image of “Bandaged moments” captures several principal issues of the verse. The displacement of the bandage from the “Soul” herself to the temporal term of imprisonment, “moments,” suggest a force sufficiently brutal to fracture the integrity of consciousness. Yet such a blow to coherence is not of central importance here. The overriding issues are those of direct injury and literal constraint. If God cannot coerce us by threats, He can always retreat to His residual source of mastery: He is more powerful than we are; He can weaken us with sickness; if all else fails, He can execute us. Thus it is God’s power to injure that this poem addresses, a power that can act quite literally as a prison.

Wolff helpfully points out that “bandaged” simultaneously refers to the literal bandaging of the eyes and to a

more general and inclusive wounding, the reiteration of God’s attack upon Jacob that may come in any number of specific afflictions, sicknesses, or losses.

See the poem “I taste a liquor never brewed” (F208), which Wolff has determined is an intertext for “The Soul has Bandaged moments.”

Sources

Guthrie, James R. Emily Dickinson's Vision: Illness and Identity in Her Poetry. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1998, 22-23.

Wolff, Cynthia. Emily Dickinson. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co., Inc. 1988, 359-360.

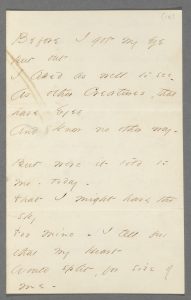

The first day’s night had come (F423, J410)

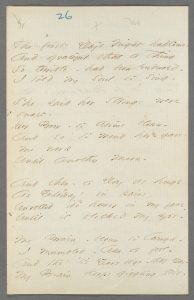

The first Day's Night had come –

And grateful that a thing

So terrible – had been endured –

I told my Soul to sing –

She said her strings were

snapt –

Her Bow – to atoms blown –

And so to mend her – gave

me work

Until another Morn –

And then – a Day as huge

As Yesterdays in pairs,

Unrolled it's horror in my face –

Until it blocked my eyes –

My Brain – begun to laugh –

I mumbled – like a fool –

And tho' 'tis Years ago – that Day –

My Brain keeps giggling – still.

And Something's odd – within –

That person that I was –

And this One – do not feel the

same –

Could it be Madness – this?

EDA manuscript: Originally in Poems: Packet XXVI, Fascicle 15 (part), Houghton Library – (141a). Includes 8 poems, written in ink, dated ca. 1862. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. First published in Unpublished Poems (1935), 13, stanzas 1-3. The entire poem was published in Bingham, New England Quarterly, 20 (March 1947), 40-41, from a transcript of A (a tr210).

Franklin dates this poem to autumn 1862. Dickinson copied it as the first poem in Fascicle 15, a placement that might mean it announces major themes for this group of poems, which includes the next poem, “We grow accustomed to the Dark” (F428A, J419), in the sixth place. It is written in short meter, stanzas of 6686 rhyming abcb, which, according to Cristanne Miller, is the second most frequently used form in Dickinson’s canon. It shares this form and its theme with another poem from this period, “He fumbles at your soul” (F477, J315), which begins in short meter but disintegrates by the end. Another important difference is the prominent agency of a “He” who targets the soul in that poem.

In “The first day’s night had come” there is no powerful force, but rather “a thing so terrible” that “had been endured.” This might refer to “the terror” Dickinson told Higginson she suffered since the Fall of 1861 (L261), but it could also be a physical loss or debility, like the eye problems that plagued Dickinson during this period. The allusion to “night” as a reprieve, as a time to “mend” her Soul’s “strings” and “bow”– that is, her means of making music or poetry–suggests that it is the light of morning that is painful to the speaker.

In the third stanza, what assails the speaker is “a Day as huge/As Yesterdays in pairs,” unrolling “it’s horror in my face–/Until it blocked my eyes.” Whatever the horror is, whether emotional, existential, or physical, it blinds the speaker, and this blinding brings on the cleaving of the self that feels like “madness.” Madness is a frequent theme in Dickinson’s poems, but as Jane Eberwein observes about this poem:

Those knowledgeable in gothic fiction may notice a normative aspect even to Dickinson’s attempts to express and experience madness by playing the madwoman role. It was, after all, one of the conventional female parts …

Whether the speaker was playing a role or narrating a real experience, this poem suggests that physical debility played a crucial part in the experience of madness.

Sources

Eberwein, Jane. Dickinson: Strategies of Limitation. Amherst: University of Amherst Press, 1985, 124.

Miller, Cristanne. Reading in Time: Emily Dickinson in the Nineteenth Century. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2012, 59.

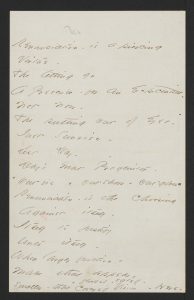

We grow accustomed to the Dark – (F428A, J419)

We grow accustomed to

the Dark –

When Light is put away –

As when the Neighbor holds

the Lamp

To witness her Good bye –

A Moment – We uncertain

step

For newness of the night –

Then – fit our Vision to the

Dark –

And meet the Road – erect –

And so of larger – Darknesses –

Those Evenings of the Brain –

When not a Moon disclose

a sign –

Or Star – come out – within –

The Bravest – grope a little –

And sometimes hit a Tree

Directly in the Forehead –

But as they learn to see –

Either the Darkness alters –

Or something in the sight

Adjusts itself to Midnight –

And Life steps almost straight.

EDA manuscript: Originally in Poems: Packet XXXII, Mixed Fascicles, Houghton Library – (174a). Includes 12 poems, written in ink, ca. 1862. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. Firs published in Commonweal, 23 (29 November 1935), 124; Unpublished Poems (1935), 16.

Dickinson copied this poem into Fascicle 15, as the sixth poem. It is one of several poems in the Fascicle that explore sight, blindness and darkness, and amplifies the themes in the previously discussed poem, “The first day’s night had come” (F423, J410). It describes a visit to a neighbor, who holds a lamp to light the visitor on her way home in the dark. The visitor/speaker must allow her vision to grow accustomed to the night so she can meet it “erect,” with confidence.

Written at a time when Dickinson stopped making social calls, even to her brother and sister-in-law, who lived next door at the Evergreens, Dickinson quickly turns this quotidian moment into an existential metaphor. In the second stanza, the familiar darkness of an Amherst evening becomes one of “larger Darknesses” and then exemplary of “Those Evenings of the Brain” characterized by a darkness so absolute as to suggest literal blindness or mental numbness.

Then, the poem takes a slightly humorous turn, describing how even “The Bravest – grope” when walking in the dark, lurching into objects, banging their foreheads into trees. This is inevitable “as they learn to see–” as either the darkness “alters– / Or something in the sight / Adjusts to Midnight–.” While some scholars, like biographer Cynthia Wolff, read this poem in a series of poems in which darkness symbolizes “God’s demise,” Maryanne Garbowsky reads it as a description of accommodation “to an abnormal situation” related to illness, like the panic attacks caused by agoraphobia, a fear of public spaces. It amplifies the allusions to incipient blindness and fear of losing one’s sight in this group of poems.

Sources

Garbowsky, Maryanne. The House without the Door: A Study of Emily Dickinson and the Illness of Agoraphobia. Rutherford, N. J.: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1989, 149-50.

Wolff, Cynthia. Emily Dickinson. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co., Inc. 1988, 452-54.

Renunciation is a piercing virtue (F782A, J745)

Renunciation – is a piercing

Virtue –

The letting go

A Presence – for an Expectation –

Not now –

The putting out of Eyes –

Just Sunrise –

Lest Day –

Day's Great Progenitor –

+Outvie

Renunciation – is the Choosing

Against itself –

Itself to justify

Unto itself –

When larger function –

Make that appear –

Smaller – that +Covered Vision – Here

+Outshow • Outglow

+flooded– • sated–

EDA manuscript: Originally in Poems: Packet XII, Fascicle 37, Houghton Library – (57c). Includes 21 poems, written in ink, ca. 1863. Courtesy of the Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. First published in Further Poems (1929), 167, in three stanzas, with the line arrangement altered and alternatives for line 9 ("Outshow") and line 16 ("sated") adopted.

Dickinson copied this poem into Fascicle 37 in late 1863 with other poems about “waiting” and renouncing. We include it here because it makes a direct reference to “The putting out of eyes,” which we saw in “Before I got my eye put out” (F336), discussed above.

Helen Vendler reads this as two poems on the abstraction “Renunciation” put together, and concludes:

we are almost forced to choose between them. The first version is the Renunciation taught by religion, which measures all values as seen by God. But the second version of Renunciation, correcting the first, is the critical virtue that Dickinson taught herself.

Dickinson's Renunciation has to do with sight, and Vendler helpfully points out that the variants for the modifier of Vision in the last line set up contradictory readings. The one Dickinson finally settles on is “Covered,” which, Vendler points out, makes “a pun on the word ‘Apocalypse’ (which means ‘The Uncovering’), when all shall be seen in its true appearance.”

By contrast, James Guthrie reads the poem in terms of Dickinson's illness:

“Renunciation – is a piercing Virtue –” completely deconstructions itself if we read it in the context of Dickinson’s metaphysical explanation of her illness. The previous poem’s [“Before I got my eye put out”] barely suppressed anger toward God resurfaces in her subversive speculation that day—more precisely, sunrise—might “Outvie” day’s “Great Progenitor,” God. Even to raise the possibility that earthly beauty might compete successfully with heaven’s interrogates the entire poem’s ostensible mood of pious self-abnegation as well as her professed acceptance of a reduced or “Covered” mode of vision. As a consequence, this poem represents, I believe, a failed attempt by Dickinson to resolve her spiritual and perceptual crisis. Yet if she could not learn to defer until after her death the pleasure she took in seeing the world, a different strategy she may have elected to pursue was to use her imagination to exchange the nighttime, which posed no threat to her eyes, for the proscribed day.

Sources

Guthrie, James R. Emily Dickinson's Vision: Illness and Identity in Her Poetry. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1998, 2, 17.

Vendler, Helen. Dickinson: Selected Poems and Commentaries. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University, 2010, 330-32.

+