“and I choose …”

Still ringing in our ears are the last words from the last poem in last week’s post:

“With Will to choose,

Or to reject, and I choose, just a crown.”

The flood of power that comes with embracing one’s agency, often associated in Dickinson’s poems with images of royalty, has the speaker feeling “adequate,” becoming “erect,” and “crowing” like a rooster over his roost—that has to warm any feminist’s heart. And because there is so much celebration in the news this week in 1862 on account of a string of Northern victories, we want to continue the mood of exultation by exploring the theme of “choosing.”

It is not clear how much choice women of Dickinson’s time, place, class and race could exercise in their lives. Within certain realms—the domestic sphere, emotional life, religion—white women of this class had scope for agency, but always granted and surveilled by men. Dickinson’s father was notoriously controlling and supervisory, but so were the gossiping tongues of relatives and neighbors in the small town of Amherst.

During this year, as she withdrew more and more from activities outside her home and even within it, Dickinson contrived a mental sphere of empowerment for herself by choosing carefully how to live her life and who to allow in it. Her niece Martha, Susan Dickinson’s daughter, recalls a childhood memory of entering Dickinson’s upstairs bedroom with her, and tells how her aunt closed the door behind them, mimed the act of turning a key in the lock and said: “It's just a turn–and freedom, Matty!”

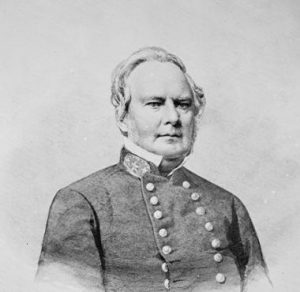

We also wanted an excuse to organize a group of poems around the incomparable poem, “The Soul selects her own Society.” When a version of the poem was published in the first collection of 1890, the editors Mabel Loomis Todd and Thomas Wentworth Higginson gave it the title “Exclusion.” While being “exclusive” sounds discriminating, as we know Dickinson was about people and silly social conventions, that word doesn’t capture the exhilaration of actively “selecting” and “choosing.” We want to explore the differences between s/electing and being s/elected; choosing and being chosen. And in the poems section, we will explore Sharon Cameron’s provocative phrase and title for her book describing Dickinson’s governing method and ethos in her fascicles, “Choosing not Choosing.”

Not that all choosing in Dickinson’s work or life was the occasion for celebration. There is exclusion in “The Soul selects her own society” and it has serious, even painful consequences. In another poem Franklin dates to late 1863, “Renunciation is a piercing virtue” (F782A, J745), the speaker finds that:

Renunciation – is the Choosing

Against itself –

Itself to justify

Unto itselfThe letting go

A Presence – for an Expectation -

Not now -

That is, sometimes the exhilaration of exercising choice is dampened by what one decides to choose. In this passage, one gives up a present joy “for an expectation.” Is it worth it?

“Who is she?”

NATIONAL

From the Springfield Republican for Saturday February 22, 1862

Review of Week: Progress of the War: “This has been a week of triumph and exultation, unbroken by a single disaster. The series of victories continues and increases in value. The victories at Fort Henry and Roanoke Island have been followed by the capture of Fort Donelson, with fifteen thousand prisoners, and all their arms and supplies, while Price has ignominiously fled into Arkansas and his army is being captured piecemeal or dispersed.”

Home Matters: “The deep interest felt in the war has taken a new start and led to extensive rejoicings over the federal victories, which will culminate in this city in public services and a splendid illumination on Saturday, the 130th anniversary of the natal day of the father of the country. His soul need not now be ashamed of his loyal children.”

Religious Intelligence: Church and Ministry. “A revival has been going on in the Northampton Methodist church, for five or six weeks past … and as a result some twenty-three persons have professed a hope in Christ.”

Opinions and Movements: “A Massachusetts soldier on the upper Potomac, recently went to hear a hardshell Presbyterian slaveholder preach, and gives the following graphic account of his style:”

Like most men of his profession who live in open violation of the moral precepts of Christ, he is a perfect tiger in doctrines. … There was not one kindly, charitable word in the whole sermon. I can easily see how such a man–so positive where modest men utter their convictions with some sort of deference to the opinions of other men, and where the great majority of hearers have very poorly defined views–should be a very effective preacher. It is in religion much as in medicine–the mass of men concern themselves so little about it that the quack who assumes the most and speaks most positively usually carries the day.

A Visitor at Washington. “Who is She?” Correspondence of the Republican.

The story is told of a certain Caliph … that he was in the habit of going about incog. to observe the state of affairs in his capital, and whenever he saw any … disturbance, or heard of any trouble or quarrel, his one question always was, “Who is she?”– thereby proving his acuteness and knowledge of the world. … Perhaps, if we were Caliphs, we might arrive at the truth as to the part woman has taken in this wild and wicked rebellion; as it is, our information is partial, but startling. Beyond the line of Mason and Dixon, (is that why it is called Dixie?) they were early aroused, and were stirring up their sons and brothers, husbands and lovers, to resist this dreadful oppression. Poor dears, they did not stop to reason–women never do; they jump at conclusions, and it is but justice to say that their impulses are often right … But in this case … nothing that woman has done since Eve ate the fruit (I never did believe it was an apple) has wrought such mischief to the country.

The writer goes on to castigate the courage of the Southern women who “have quilted quinine into their skirts, and carried arms in their trunks” to support their fighting men and exclaims:

How they have taken advantage of our proverbial national courtesy to women.

But in the next breath, he recounts:

I know a man who applied for a certain post [in Washington] and he was well fitted for it, and had some claim. But, the highest lady in the land (who is she?) said, “Tell him he cannot have it, I have promised it elsewhere;” and she carried her point. It is certain we are indebted to the same influence for some very curious appointments, more curious than suitable.

We will see many more criticisms of Mrs. Lincoln from this source in the coming weeks.

Books, Authors and Art. Notes a new edition of the popular author Bayard Taylor, and recommends a passage from “A Young Author’s Life in London,” which is relevant to Dickinson’s upcoming correspondences with Higginson:

O, the dreams we dream! O, the poems we write! Kind are the hands that hold us back from rushing into print; tender the words which pronounce such harsh judgments upon our works. For a year, we proudly curse the stupidity of our advisers; forever afterwards we bless them as benefactors. Reader, that knoweth, peradventure, how many bad poems I have published, little dreamest thou how many worse ones a kind fate has saved me from offering thee.

The article concludes: “The reader will perhaps be reminded of those playful lines of Lowell’s:

While you were thinking yourself to be pitied,

Just think how much harder your teeth you’d have gritted,

It ‘twere not for the dullness I’ve kindly omitted.”

Original Poetry: Printed “February” a long poem in tetrameter quatrains rhyming abab about the coming spring as a metaphor for the peace of summer longed for by the nation. [We found this poem in a volume titled A Quiet Life and Other Poems by EDR, or Elizabeth Dickinson Rice Biancardi 1833-1885, author of At home in Italy, NY: Houghton Mifflin and Co, 1884, but could find no more information on her.] “The Photograph Album,” in the same form, about the fear of loss of a loved one. “Along the Lines” uses a more rousing ballad measure to evoke the men fighting the rebellion, and “My Love,” a humorous poem in common meter of 8 line stanzas describing the speaker’s passion for an ill-favored man [which gets reprinted in the Labor Digest and other books about workingmen]:

My love, dear man, turns in his toes,

My love is tangle-kneed,

Cross-eyed, left-handed, hair and beard

In hue are disagreed.

He has no soft and winning voice,

No single charm has he.

And yet, this awkward, ugly man

Is all the world to me.

In Selected Miscellany: Two poems: “Into the Darkness” by Mary Forest, in iambic tetrameter quatrains with variable rhyming, about the inevitability of death. “The Compass” by S. D. Robbins, iambic pentameter quatrains rhyming abab about God as the speaker’s moral index.

Also, from Gail Hamilton, “The Time to Make Love to a Woman”– after she has been jilted by another; “The Army of the English Commonwealth” by John Milton, the men of which, he claims, were exemplary for reading scripture and hearing sermons in their off-hours; “The Women of a Nation” by Alexis de Tocqueville, who, though he argues that women are sometimes a positive and redeeming influence on men, most often are negative influences because “the grand notion of public duty was entirely absent” from their minds. “Stick to your Opinions” by John S. Hart, “Baby Talk” a complaint about the degeneration of the language from the novel Vanity Fair.

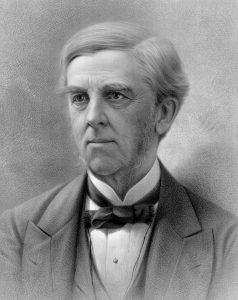

Hampshire Gazette for February 25, 1862, publishes on its first page from the Atlantic for March, “Voyage of the Good Ship Union” by Oliver Wendell Holmes, with 8 line stanzas of two quatrains of ballad measure rhyming ababcdcd and ending,

One flag, one land, one heart, one hand,

One Nation, evermore!

Besides coverage of the war they print a column on “A Royal Courtship,” about the late Prince Albert’s courtship of Queen Victoria, and “A Few Reflections on Boys” about how to raise honorable men.

INTERNATIONAL

From the Springfield Republican, February 22, 1862: “In the January number of the Westminster Review is an interesting article on the Religious Heresies of the Working Classes of England. In speaking of the atheism of a certain class of unbelievers, it is said that they carry their opposition to theism so far that their organs strike out the word ‘God’ in all poetry they quote. Thus, the ‘National Reformer,’ having occasion to quote, to serve its own purpose, Bryant’s celebrated stanza, beginning–

Truth crushed to earth will rise again,

The eternal years of God are hers

[from William Cullen Bryant (1794-1878) “The Battle-Field,” ll. 33-34, which was made into a hymn. The first, famous line was quoted by M. L. King and gave the title to an album by the hip hop group House of Pain] alters the second line in this way,

Surely eternal years are hers.

In the minds of these bigots of atheism, Truth may be eternal, but God cannot be permitted to have even a momentary poetical existence.”

“Joyful Victory”

On February 17, the Springfield Republican reported that Edward Dickinson had been re-elected president of the Amherst, Belchertown and Palmer Railroad for the current year. See Dickinson's poem about the railroad, “I like to see it lap the miles” (F383A, J585), written in 1862.

On February 20 the town of Amherst rang the bells to celebrate the news of the capture of Fort Donelson.

The stars and stripes were unfurled from the tower of the chapel and cheer on cheer rose from College hill.

And on February 22, a short notice in the news from Amherst, which presages the tragedy to come:

We have just ascertained that the son of President Stearns [of Amherst College 1854-1876], engaged in the battle of Roanoke as Adjutant, was slightly wounded on the head. So we feel quite glorious over our share in the joyful victory.

Reflection

Charif Shanahan

To spend a life

In choice –

Not in having chosen, but in

Choosing –

A choice of its own

I suppose –

A railway paved as it goes –

The figs –

Ripe and dropping

From the encumbered boughs –

Before reach –

O Natural World

To commit – to be –

O to be certain so –

I was recently in Amherst for the first time and took the opportunity to visit Dickinson’s home. Unfortunately, the house was closed for the winter months, though I did have the chance to walk around and feel the energy of the estate. While there I recalled the details of a visit to Dickinson’s house that the great poet Jorie Graham had shared in an interview for Slate. Graham, pregnant with a child and at something of a crossroads in her life, was seeking guidance, direction from outside herself about how to proceed—perhaps from Dickinson’s spirit itself, still so alive in that small town it is almost tangible. During her visit, Graham noticed, on or near the poet’s grave, a ladybug, which then flew up and landed on her hand for a moment before flying in the direction of the Homestead. Graham followed the ladybug to Dickinson’s house, which was closed—for the winter season, as it was for me, or perhaps for renovations; I can’t recall the details. I do recall that Graham managed to convince the attendant to let her enter not only the house, but Emily’s upstairs bedroom where, incredibly, Graham found, next to Emily’s impossibly narrow desk, a small wooden crib—a sign to continue on the path of making poems in the face of imminent motherhood.

It’s likely I’m misremembering some details of Graham’s story—I looked for the interview in the Slate archives, but was unable to find it—though the story, as it exists in my memory, has stayed with me since I first encountered it years ago as an MFA candidate in New York City: I was struck that a poet as visionary and accomplished as Graham might, like myself and so many of the young poets I knew then personally, question how, or whether at all, to continue on a path of making poems. Given the demands of the world that might take us away from the craft, or simply given the other commitments one could choose to make in this life—some more clearly mapped, with fewer obstacles and less resistance, than a life of writing poems—I was encouraged to discern that the doubt, the questioning might simply be a part of the path that lies before any artist—of any age, background, experience, or life stage. As sentimental as it sounds, I think of the story—and of poetry—whenever I see a ladybug.

Years after first hearing Graham’s story, with a book of my own now in the world, I am grateful for the opportunity to re-read Dickinson’s poems “of choosing”—in her case, not only her art, but her reclusive life—and to be reminded of the many ways to be a poet in the world and of the responsibility we share to reflect the world back to itself, however we can.

At a time when so many of us carry a sense of helplessness and dread in the face of unimaginable greed, rampant and institutionally-sponsored violence, and the dehumanization of our brothers and sisters all around the world, I am “Held fast … By my own Choice” to engage in exactly the kind of truth-telling work that poetry allows. I sit in the Ferry Building of downtown San Francisco, looking into the open expanse above the Bay, on the opposite side of our “ample nation”—itself at a kind of crossroads and in need of the compassion and action that poetry can offer and inspire in us—and think of Dickinson at her small desk writing these lines:

A still – Volcano – Life -

That flickered in the night -

When it was dark enough to do

Without erasing sight -

Bio: Charif Shanahan is the author of Into Each Room We Enter without Knowing (SIU Press, 2017), winner of the Crab Orchard Series in Poetry First Book Award. His poems appear in New Republic, New York Times Magazine, PBS NewsHour, and elsewhere. Called a "vital and profound new voice" by Publishers Weekly, Shanahan is the recipient of awards and fellowships from the Academy of American Poets, Cave Canem Foundation, the Frost Place, the Fulbright Program/IIE, Millay Colony for the Arts, Starworks Foundation, and Stanford University, where he was a Wallace Stegner Fellow in Poetry. Originally from the Bronx, he is now an Assistant Professor of English at Northwestern University.

Sources

History

Hampshire Gazette, February 25, 1862

Springfield Republican, February 22, 1862

Helpful, and illuminating. With Dickinson – insights help decode. So Thanks! Fern Leaf.

So glad you find the posts illuminating. I hope you keep reading and tell your friends about White Heat!