On Choosing the Poems from Fascicle 12

Because we could not focus on all the poems in the fascicle and have already discussed several in earlier posts, we chose poems that exemplify Fascicle 12’s imagery of God and sound, and the ambivalence and agnosticism that emerges in relation to these motifs. Each poem in Fascicle 12, except perhaps “I taste a liquor never brewed –,” questions the power of the divine, either through an abstract concept labeled immortality or a reference to God. “Many a phrase” stands out in this respect due to its lack of divine imagery, but the last two lines may allude indirectly to the subject, especially in the context of this fascicle: “Say it again, Saxon! / Hush, only to me!” Saxon is a word associated with Dickinson’s “Master Documents,” and one interpretation of the identity of the “Master” is God.

In terms of sound, “I got so I could hear his name –” and “Many a phrase has the English language –” both explore sound as an agent of “extasy,” love, fear, power, and perhaps even divine manifestations. Every poem also has a unique metric rhythm to it, especially when we take Dickinson’s own written line breaks into account.

“I taste a liquor never brewed -” starts the fascicle off, and hence colors the fascicle’s first impressions and initial thematic explorations. Perhaps this fascicle means to inebriate the reader, or transport the reader to another scale of space. It is worth thinking about the differences of scale in this fascicle as well—starting as small as bees and butterflies, ending with God and immortality.

Cristanne Miller dates Fascicle 12 from “early 1861” (sheet 1) to “early 1862” (sheet 2 on to sheet 8); “early” here is only in terms of the year, as the presence of the poem “One Year Ago – jots what?” indicates Dickinson was still working on it in April (as the date discussed in the poem is the anniversary of the Civil War, April 12th). The Fascicle contains twenty-six poems, including some well known ones. Here is the list in the order Miller assigns them:

Sheet One

- I taste a liquor never brewed–

- Pine Bough/A feather from a Whippowil

- I lost a World –the other day!

- I’ve heard an Organ talk, sometimes–

- A transport one cannot contain

- “Faith” is a fine invention

Sheet Two

- I got so I could hear his name–

- A single Screw of Flesh

- A Weight with Needles on the pounds–

Sheet Three

- Father–I bring thee–not myself–

- Where Ships of Purple–gently toss–

- This-is the land–the Sunset washes–

- The Doomed–regard the Sunrise

- Jesus! thy Crucifix

- Did we Disobey Him?

Leaf Four

- Unto Like Story– Trouble has enticed me–

Sheet Five

- One Year ago–jots what?

- It’s like the Light –

- Alone, I cannot be–

Sheet Six

- He put the Belt around my life –

- The only Ghost I ever saw

Sheet Seven

- Doubt me! My Dim Companion!

- Many a phrase has the English language–

Sheet Eight

- Of all the Sounds despatched abroad–

- Her smile was shaped like other smiles–

The meaning of the Fascicles, of course, is a matter of interpretation. This one focuses on themes of religion and sound—or at least has a good range of poems containing God or godlike imagery and sonic qualities, both in meter and in imagery that could inform the readings of these poems.

“I taste a liquor never brewed” (F 208A, J214)

I taste a liquor never brewed –

From Tankards scooped in Pearl –

Not all the +Frankfort Berries

Yield such an Alcohol!

Inebriate of air – am I –

And Debauchee of Dew –

Reeling – thro’ endless summer days –

From inns of molten Blue –

When “Landlords” turn the drunken Bee

Out of the Foxglove’s door –

When Butterflies – renounce their “drams” –

I shall but drink the more!

Till Seraphs swing their snowy Hats –

And Saints – to windows run –

To see the little Tippler

+From Manzanilla come!

+Vats opon the Rhine +Leaning against the – Sun -

EDA manuscript: "Originally in Packet XIV, Mixed Fasciles, ca. 1860-1862. First published in Springfield Daily Republican (4 May 1861), 8, from the lost copy; also Springfield Weekly Republican (11 May 1861), 6. Poems (1890), 34, from the fascicle, with both alternatives adopted, under the title “The May Wine.” Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA."

Cristanne Miller suggests a few contemporary influences for this poem that opens Fascicle 12: Longfellow’s “Catawba Wine” and Emerson’s “Bacchus,” both of which Dickinson would have known. The bee in the foxglove echoes Keats’ “O Solitude.” The unforgettable lines describing the speaker as “Inebriate of air – am I – / And Debauchee of Dew –,” also recall Emerson’s description of “The Humble-Bee” as “Insect lover of the sun” and “Epicurean of June.” “Manzanilla” is, according to Dickinson’s Lexicon, a “City on the southern coast of Cuba; important commercial center known for the export of rum,” which becomes a figure for “drunkenness, inebriation.” Another source is Emerson’s important essay, “The Poet,” published in his collection, Essays: Second Series in 1844 and based on a lecture (attended in New York by Walt Whitman), where he affirmed:

The poet knows that he speaks adequately, then, only when he speaks somewhat wildly, or, “with the flower of the mind;” not with the intellect, used as an organ, but with the intellect released from all service, and suffered to take its direction from its celestial life; or, as the ancients were wont to express themselves, not with intellect alone, but with the intellect inebriated by nectar. … The sublime vision comes to the pure and simple soul in a clean and chaste body. … Milton says, that the lyric poet may drink wine and live generously, but the epic poet, he who shall sing of the gods, and their descent unto men, must drink water out of a wooden bowl. For poetry is not “Devil’s wine,” but God’s wine.

It is intriguing to note that Dickinson’s Webster’s gives a gendered definition for “debauchee:” “A man given to intemperance, or bacchanalian excesses. But chiefly, a man habitually lewd.”

Many readings of this poem focus on the comedy, the intoxication of and in nature, and the final stanza’s opening to the universe as a sign of power and accomplishment. Karl Keller opines:

Her drunk poet … is not at all an Emerson intellectual speaking wildly but, oxymoronically and humorously, a drunk Congregationalist, a religious drunk: the pure transcendental mind and chaste transcendental body have become by worldly standards debauched and by heavenly ones heretical.

In the context of the Fascicle, this poem sets the stage for experiences of “transport.”

Sources

Emerson, Ralph Waldo. “The Poet.” Essays: Second Series. 1844

Emerson , Ralph Waldo. Poems. The Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson, vol. 9 [1909].

Hallen, Cynthia, ed. Emily Dickinson Lexicon. Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University, 2007.

Keller, Karl. The Only Kangaroo Among the Beauty. Emily Dickinson and America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1979.

Miller, Cristanne. “Immediate U.S. Literary Predecessors.” Emily Dickinson in Context. Ed. Eliza Richards. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013: 119-128, 121.

“I got so I could hear his name” (F292A, J293)

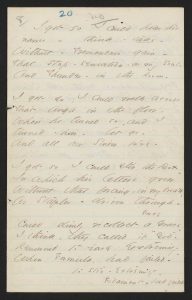

I got so I could hear his

name –

Without – Tremendous gain –

That Stop-sensation – on my Soul –

And Thunder – in the Room –

I got so I could walk across

That Angle in the floor,

Where he turned so, and I

+turned – how –

And all our Sinew tore –

I got so I could stir the Box –

In which his letters grew

Without that forcing, in my breath –

As Staples – driven through –

Could dimly recollect a +Grace –

I think, they called it “God” –

Renowned +to ease Extremity –

When +Formula, had failed –

And shape my Hands –

Petition’s way,

Tho’ ignorant of a word

That Ordination – utters –

My Business – with the Cloud,

If any Power behind it, be,

Not +subject to Despair –

It care – in some remoter way,

For so minute affair

As Misery –

Itself, too +great, for interrup –

ting – more –

+ let go – +Force

+to stir – Extremity -

+ Filament – had failed -

+Supremer than – • Superior to – Despair

+ vast

EDA manuscript: "Originally in Packet XX, Fascicle 10, ca. 1861. First published in London Mercury, 19 (February 1929), 357; New York Herald Tribune Books (10 March 1929), 4, and Further Poems (1929), 183-84. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA."

This poem appears after “Faith is a fine invention” (F202A, J185), with its skepticism about religious faith in relation to the modern science of “Microscopes,” and before “A Single Screw of Flesh,” which is the next poem discussed. It darkens the mood from the euphoria of “I taste a liquor never brewed” and the wry tone of “Faith is a fine invention.” Read alone, this poem is often interpreted as the end of a love affair—the meeting in a room, the letters accumulating in a box. In the context of the fascicle, the emphasis falls on the aftermath of a traumatic event and the subsequent loss of faith, of surviving the blow and living on after it.

The struggle takes on physical dimensions and a rather specific location, “That Angle in the floor, / Where he turned so, and I / turned – how/ and all our Sinew tore –.” “Turning” in religious terms usually means a turning towards God, the first step in the conversion process. Here, it seems to mean the opposite, turning away from faith. The word “Sinew” brings us into the Biblical story from Genesis 32:22-31 of Jacob wrestling with the Angel. Jacob, grandson of Abraham and Sarah, is injured in his thigh but prevails and gets a blessing. This word also appears in “I Rose – because he sank” in last week’s post. It is significant that the speaker in this poem can barely remember “Grace” and “God,” can barely shape her hands to pray.

Sharon Cameron reads this poem as an example of “knowledge that dares not scrutinize itself” and “narrative breakdown.” She argues that the point of too much pain produces

rhythmic transformations in the last three stanzas: full rhyme disappears, the common particular meter established in the first three stanzas gives way to variation, as does the regular four-stress line. Such rhythmic change also counterpoints the paraphrasable sense of the lines.

Finally, Cameron concludes, the poem,

though not, I suspect, intentionally, is about what it is like to trivialize feeling because, as is, feeling has become unendurable. Better to make it nothing than to die from it.

Sources

Cameron, Sharon. Lyric Time: Dickinson and the Limits of Genre. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1979, 58-61.

“A single screw of flesh” (F293A, J263)

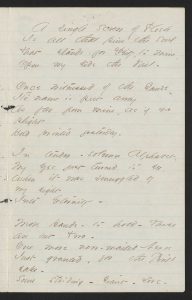

A single Screw of Flesh

A single Screw of Flesh

Is all that pins the Soul

That stands for Deity, to mine,

Opon my side the Vail –

Once witnessed of the Gauze –

It’s name is put away

As far from mine, as if no

plight

Had printed yesterday,

In tender – solemn Alphabet,

My eyes just turned to see –

When it was smuggled by

my sight

Into Eternity –

More Hands – to hold – These

are but Two –

One more new-mailed Nerve

Just granted, for the Peril’s

sake –

Some striding – Giant – Love –

So greater than the Gods

can show,

They slink before the Clay,

That not for all their Heaven

can boast

Will let it’s Keepsake – go

EDA manuscript: "Originally in Packet XX, Fascicle 10, ca. 1861. Unpublished Poems (1935), 107.Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA."

This troubling and difficult poem follows “I got so I could hear his name” and continues in its agonized tone. Much hangs on the opening word, “screw.” Judith Weissman argues that in this word Dickinson

speaks more blasphemy than many whole volumes by other nineteenth-century writers. Souls are not supposed to be pinned to each other by screws of flesh–and we can suspect that Dickinson knows what “screw” means in obscene slang. Furthermore, one human soul is not supposed to stand for deity to another.

Another notable phrase is “new-mailed Nerve,” which the Lexicon defines as “suddenly shielded, now protected with plates of armor.” But sounding like “new-nailed,” it thus calls up Christ’s crucifixion. Other meanings it offers are “sent off recently; dispatched,” with the figurative meanings of “fired; sparked; activated; triggered; set off.”

And an expansive, even hopeful phrase: “Some striding – Giant – Love –” describing an emotion so vast it makes the Gods “slink” before it.

Sources

Hallen, Cynthia, ed. Emily Dickinson Lexicon. Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University, 2007.

Weissman, Judith. “Transport’s Working Classes: Sanity, Sex, and Solidarity in Dickinson’s Late Poetry.” Midwest Quarterly 29.4 (Summer 1988): 407-24, 408-09.

“Father – I bring thee – not myself” (F295B, J265)

Father – I bring thee – not

myself –

That were the little load –

I bring thee the departed

Heart

I had not +strength

to hold –

The Heart I cherished

in my own

Till mine – too heavy grew –

Yet – strangest – heavier –

since it went –

Is it too large for you?

+power

EDA manuscript: "Originally in Packet XX, Fascicle 10, ca. 1861. First published in Poems (1896), 88, from the fascicle. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA."

This poem is the eleventh poem in the fascicle, one poem away from “A Single crew of Flesh” and by comparison with the poems that precede it, seems like the eye of the storm. It confirms that another’s “heart” is involved in the speaker’s religious struggles. And though the tone is simple and straightforward, it contains some classic Dickinson moves. The self-abasement in terms of scale: her speaker is “little” compared to the bigger heart of the beloved; the strangeness of the heart/loss growing heavier with its absence; the weightiness of absence and renunciation; the simple question at the end.

“Many a phrase has the English language” (F333A, J276)

Many a phrase has the

English language –

I have heard but one –

Low as the laughter of the

Cricket,

Loud, as the Thunder’s Tongue –

Murmuring, like old Caspian

Choirs,

When the Tide’s a’lull –

Saying itself in new inflection –

Like a Whippowil –

Breaking in bright Orthogra–

phy

On my simple sleep –

Thundering it’s Prospective –

Till I – +stir, and weep –

Not for the Sorrow, done me –

But the – +push of Joy –

Say it again, Saxon!

Hush – Only to me!

+ Grope – start +Pain of joy

EDA manuscript: "Packet XIV, Mixed Fasciles, ca. 1860-1862. First published in Unpublished Poems (1935), 89, with the alternatives not adopted. Courtesy Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA."

This is the twenty-fourth poem in the fascicle, and it seems to take us into the aftermath of a startling event, somewhat distant from the bitter agony of some of the earlier poems in the group.

This is a riddling poem about the power of language and the experience of hearing it spoken. It asks: what is the phrase, spoken to the speaker that has such various and lush timbres? Caspian, according to the Lexicon, is “the largest lake in the world … located in northern Iran.” The “Whippowil” also appears in the second poem in the fascicle. It is a nocturnal bird with a haunting song, sometimes regarded as an omen of death

“Saxon” according to the Lexicon refers to the “Germanic tribe that conquered the Celts in Britain” and stands for the English language. There is something delicious in the secret whispered only to the speaker, but it is characteristically ambivalent: the speaker is moved, haunted, awakened and weeps not for sorrow but “for the push/pain of joy.”

Sources

Hallen, Cynthia, ed. Emily Dickinson Lexicon. Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University, 2007.

“Of all the sounds despatched” (F334A, J321)

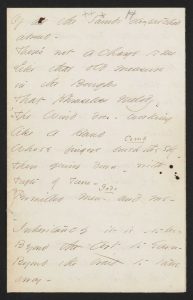

Of all the Sounds despatched

Of all the Sounds despatched

abroad –

There’s not a charge to me

Like that old measure

in the Boughs

That phraseless Melody –

The Wind does – working

like a Hand

Whose fingers brush the Sky –

Then quiver down – with

Tufts of Tune –

Permitted +men – and me –

Inheritance it is – to us –

Beyond the Art to Earn –

Beyond the trait to take

away –

By Robber – since the Gain

Is gotten, not with fingers –

And inner than the Bone –

Hid golden – for the whole

of Days –

And even in the Urn –

I cannot vouch the merry

Dust

Do not arise and play –

In some odd fashion

of it’s own –

Some quainter Holiday –

When Winds go round

and round, in Bands –

And thrum opon the Door –

And Birds take places – Overhead –

To bear them Orchestra –

I crave him grace – of

Summer Boughs –

If such an Outcast be –

He never heard that

fleshless Chant

Rise solemn, in the Tree –

As if some Caravan of

sound

On Deserts, in the Sky

Had broken Ran (k) –

Then knit – and +passed –

In Seamless Company –

+Gods +swept

EDA manuscript: "Originally in Packet XIV, Mixed Fasciles, ca. 1860-1862. First published in Higginson, Christian Union, 42 (25 September 1890), 393, in part, as two eight-line stanzas. Poems (1890), 96-97, in part, from the fascicle (A), as five stanzas of 4, 4, 4, 4, and 5 lines; the alternative for line 8 was adopted. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA."

This poem follows directly after “Many a phrase has the English language,” and continues the theme of heard language or sound in the many sounds of the wind. William Shurr argues that the poem develops

a comparison between the way the wind moves across the landscape and the way the hand of a lover moves across a woman’s body.

There is certainly sensuous pleasure in hearing “that phraseless Melody,” and also in contemplating how the wind “plays” with the “Dust,” which suggests the poet’s own play with im/mortality and the “fleshless chant” of poetry. The final images of an exotic desert caravan first breaking rank, then knitting back together and passing on “in seamless Company” evokes the restless, non-conforming poetics of the poet herself.

Sources

Shurr, William. The Marriage of Emily Dickinson: A Study of the Fascicles. Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 22.