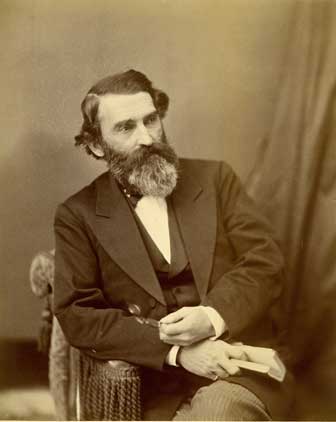

During August 1862, Dickinson wrote only two letters that survive to give us a glimpse into her mood and concerns: her fifth letter to Thomas Wentworth Higginson (L270), discussed in a previous post, and a letter to Samuel Bowles (1826-1878), owner and editor-in-chief of the Springfield Republican and family friend of the Dickinsons, who had been touring Europe for his health since the spring. This week, we take our cue from this letter to Bowles (L272), in order to continue incorporating letters into our gathering of primary texts and to explore themes Dickinson includes in that letter.

During August 1862, Dickinson wrote only two letters that survive to give us a glimpse into her mood and concerns: her fifth letter to Thomas Wentworth Higginson (L270), discussed in a previous post, and a letter to Samuel Bowles (1826-1878), owner and editor-in-chief of the Springfield Republican and family friend of the Dickinsons, who had been touring Europe for his health since the spring. This week, we take our cue from this letter to Bowles (L272), in order to continue incorporating letters into our gathering of primary texts and to explore themes Dickinson includes in that letter.

In her letter, Dickinson expresses her longing for Bowles in terms of the changing of the seasons, from late summer to fall, and through the figure of a bee and its clover. Bees are arthropods, and represent a large trove of images Dickinson drew on frequently. Medical Entomologist Louis C. Rutledge notes that 180 of Dickinson’s 1775 poems (according to Johnson’s 1955 edition)—more than 10%—refer to one or more arthropods, including her first poem and her last.

As an important pollinator of plants, bees are under severe threat in our time because of environmental challenges, and we wanted to bring attention to that. We also nod to a whimsical essay in Harper’s Monthly for August 1862 about “a fairy that had lost the power of vanishing” and appears in the form of cheerful crickets, another prevalent arthropod in Dickinson’s writing. With this focus, we bring attention to arthropods, explore the role and symbolism of bees in particular for Dickinson, which can be quite racy, and of anthropomorphism more generally in her writing.

“Authors ought to be Read and not Heard”

Springfield Republican, August 23, 1862

Progress of the War, page 1

“The great event of this week has been the transfer of Gen. McClellan’s army to Yorktown [end of the Peninsula Campaign]. Not the slightest molestation was suffered from the enemy during the perilous operation.”

How Do These Men Feel? page 4

“When a man is praised by a scoundrel he ought to suspect himself. The Memphis (Grenada) Appeal, the most malignant of all rebel sheets, praises Seymour of Connecticut, Wood of New York, Vallandigham of Ohio, and ex-president Pierce as the only true friends the South can count upon in the North.”

Mexico and the West Indies, page 4

“The steamer Columbia, from Havana, has arrived at New York. The yellow fever was decreasing, but for the past month had been very fatal.”

Poetry, “Ministering Angels” [by Adelaide Anne Procter], page 6

Conversational Powers, page 6

“The late William Hazlitt was of opinion that authors were not fitted, generally speaking, to shine in conversation. ‘Authors ought to be read and not heard.’ Some of the greatest names in English and French literature, men who have filled books with an eloquence and truth that defy oblivion, were mere mutes before their fellow men. They had golden ingots, which, in the privacy of home, they could convert into coin bearing an impress that would insure universal currency; but they could not, on the spur of the moment, produce the farthings current in the marketplace.”

Book, Authors, and Arts, page 7

“A French novel is often an odd compound of fiction and philosophy; but when it is the work of a master, like Victor Hugo, each of these qualities is admirable in its own way. His philosophy is always piquant and readable and raises a thousand questions where it answers one. He drops here a theory and there an epigram, here a sketch from fancy and there a photograph from life, and then puts them all aside for the moment, or rather mingles them all, as he plunges into one of the most exciting stories of the day.”

Hampshire Gazette, August 26, 1862

Literary: Poems of Mrs. Browning, page 1

“Mrs. Elizabeth Barrett Browning ‘as a poet, stands among women unrivaled and alone. In passionate tenderness, in capriciousness of imagination, freshness of feeling, vigor of thought, wealth of ideas and loftiness of soul, her poetry stands alone amongst all that has ever been written by women.’ That opinion, comprehensive in its flattery, we readily adopt in lieu of any praises of our own.”

Amherst, page 3

“The enrolled militia of Amherst number a little more than 400, making the chance for a draft one in ten.”

Harper’s Monthly, August 1862

Tommatoo, page 325

“A fairy that had lost the power of vanishing, and was obliged to remain ever-present, doing continual good; a cricket on the hearth, chirping through heat and cold; an animated amulet, sovereign against misfortune; a Santa Claus, without the wrinkles, but young and beautiful, choosing the darkest moments to leap right into one’s heart, and drop there the prettiest moral playthings to gladden and make gay—such, in my humble opinion, was Tommatoo.”

“Jerusalem Must be like Sue’s Drawing Room”

Samuel Bowles was a handsome, charming and passionate man whose literary interests and public position appealed to Dickinson. He became friends first with Susan and Austin Dickinson, who hosted him many times at the Evergreens. In her “Annals of the Evergreens,” Sue wrote about him in glowing terms:

[He] seemed to enrich and widen all life for us, a creator of endless perspectives. … His range of topics was unlimited, now some plot of local politics, rousing his honest rage, now some rare effusion of fine sentiment over an unpublished poem which he would draw from his pocket, having received it in advance from the fascinated editor.

Dickinson met him in June 1858 at the Evergreens and immediately afterwards wrote him in passionate terms (apparently, “purple” was a color she thereafter associated with him):

Though it is almost nine o'clock, the skies are gay and yellow, and there's a purple craft or so, in which a friend could sail. Tonight “Jerusalem.” I think Jerusalem must be like Sue’s Drawing Room, when we are talking and laughing there, and you and Mrs Bowles are by (L189).

Especially during the difficult period of 1861-62, Dickinson considered Bowles a special confidante and wrote him frequently, although the friendship suffered a breach which was not repaired until the death of Edward Dickinson, Dickinson’s father, in 1874. Some scholars consider Bowles a likely candidate for the person Dickinson addressed as “Master” during this period. Over the course of their relationship, she sent him 40 poems, and though he was a passionate supporter and publisher of women’s poetry, he never published any of them.

The letter Dickinson wrote to him this month in 1862 expresses her longing in revelatory terms. We focus on the allusion to bees, which comes at the end of the letter in a question:

Sue gave me the paper, to write on – so when the writing tires you – play it is Her, and “Jackey”- and that will rest your eyes – for have not the Clovers, names, to the Bees?

Dickinson refers to the special thin, air-mail stationery Sue gave her to write on. “Jackey” was the name Austin and Sue used for their first son Ned while still a baby. Dickinson suggests that if Bowles gets tired of her letter, he can “play” or pretend it is Sue and her son who are writing, comparing them to “the Clovers” that bees identify by name. This obscure reference gains clarity when we explore Dickinson’s wider use of bees in her writing.

Speaking broadly about Dickinson’s frequent references to animals and her attribution of subjectivity to them, Aaron Shakleford argues that Dickinson’s anthropomorphism

uncovers just how limited our own consciousness and epistemology really is, while also demonstrating how this shapes our knowledge of animals. … [Dickinson] demonstrates how to navigate both our inescapable reliance upon the human to "know" the external world and the limitations of our own ability to understand that world.

More specifically, in her study of Dickinson’s gardens, Judith Farr notes the dual symbolic valence of bees. On the one hand, Dickinson

More specifically, in her study of Dickinson’s gardens, Judith Farr notes the dual symbolic valence of bees. On the one hand, Dickinson

contemplated the sexual arena of her garden daily. There, the careers of flowers and the dramatic career of the bee as their lover/propagator commanded her attention, for “till the Bee / Blossoms stand negative” (F999).

Thus, bees often emblematize a promiscuous masculine sexuality (though worker bees are female), and the drama of active (masculine) bee and passive (submissive) flower figures a gendered human theater of love, intimacy, and desire. On the other hand, in her playful/heterodox revision of the Christian trinity dated to 1858, Dickinson prayed:

In the name of the Bee –

And of the Butterfly –

And of the Breeze – Amen!

(F23A)

Thus, as several scholars observe, Dickinson links the gendered sexuality figured by bees to Puritan doctrines of conversion and salvation as well as her own revisions of spirituality. According to Victoria Morgan,

Dickinson disrupts the industriousness culturally associated with bees by employing bee imagery in her depictions of physical and spiritual excess and pleasure. … Dickinson’s excessive bees emulate the “dangerous” sexuality that is forbidden, but also embody the rhapsodic spiritual pleasure which organized religion attempts to name and own.

Taking this one step further, H. Jordan Landry sees Dickinson’s bees as essentially “queer.” Although, as Dickinson would have known, worker bees are all female, she clearly marks them as male and penetrative. Still, they engage in what can be read as the lesbianic sexual act of cunnilingus with the feminine flower. According to Landry, Dickinson’s bee imagery

aims at reorganizing the experience, perception, and value of the female anatomy and rewriting its capacities to be pleasured and give pleasure.

Furthermore, Landry argues that Dickinson overlays this rewriting onto Puritan conversion in which Dickinson felt women were regarded as secondary. Landry reads Dickinson’s bee imagery through her early letters to Sue and the queer desires that can be discerned there. In the letter to Bowles, the bee image is connected to Sue and her young son but directed at Bowles. Is he the “bee” who names, recognizes and pollinates specific clovers? Does this imagery signify differently when Dickinson deploys it to express her longing for Bowles? What queerness inheres in that relationship?

Furthermore, Landry argues that Dickinson overlays this rewriting onto Puritan conversion in which Dickinson felt women were regarded as secondary. Landry reads Dickinson’s bee imagery through her early letters to Sue and the queer desires that can be discerned there. In the letter to Bowles, the bee image is connected to Sue and her young son but directed at Bowles. Is he the “bee” who names, recognizes and pollinates specific clovers? Does this imagery signify differently when Dickinson deploys it to express her longing for Bowles? What queerness inheres in that relationship?

Reflection

Efrosyni Manda

A letter requires two communicating poles and its presence presupposes the absence of one of them. It is meant to efface the very gap that brought it to the surface by drawing the poles together. Senders were advised to include trivial and gossipy details of their microcosm in their letter so as to relieve the recipient’s pain of separation. However, these moments gone away forever widen the gap since they accentuate absence and exclusion.

A letter requires two communicating poles and its presence presupposes the absence of one of them. It is meant to efface the very gap that brought it to the surface by drawing the poles together. Senders were advised to include trivial and gossipy details of their microcosm in their letter so as to relieve the recipient’s pain of separation. However, these moments gone away forever widen the gap since they accentuate absence and exclusion.

In her letter to Samuel Bowles, Emily Dickinson carries the macrocosm of Nature, the Hills, the flowers and the bright autumnal Skies, over to him in an effort to retain a shared referential point, a cosmos that, regardless of the seasonal changes, is permanent, always waiting for him to come back to her. Time is inextricably bound with space and it is chopped away through a peculiar countdown: its passing is not measured by the linear succession of days or months; rather, it’s the changes in nature that constitute milestones towards Bowles’ return. Time is too abstract and immaterial for her to handle; she has to materialize it in its concrete symbols. The Grape, the Pippin, the Chestnut, separated with dashes yet squeezed into the same sentence, resemble a rapid time lapse and constitute tangible proofs that time has indeed passed, that his coming back gets closer. Unlike time in the poem, “If you were coming in the Fall,” which opens up to infinity, in this letter, time moves painfully slowly, closing steadily in to his return, “[Him]self”.

The absence/presence of the sender/receiver of a letter is mutually interchangeable and negated; concurrence of the poles is impossible. Dickinson’s letter, a communicative device which relies on the metaphor, becomes the vehicle that brings her to Bowles. She carries her parousia over to him; her writing travels through time and space to meet and possibly tire him. Painfully aware of the “Sea” between them, she tracks the steamer that took him away in an attempt to wipe away the ocean that separates them. The projection of his spatiotemporal zone into hers makes them coincide, even apparitionally, and she constructs an a-temporal, a-spatial niche in which the epistolary displacement is annulled so that they can touch each other; he has already returned and rings her bell. Her attempt to coordinate their spatiotemporal zones obscures or even eliminates the boundaries of the epistolary cosmos and produces time textually, allowing Dickinson’s live streaming interaction with Bowles.

Bio: Efrosyni Manda holds a BA in English Literature and Culture and an MA in Translation Studies. She is a PhD Candidate at the University of Athens, Greece. She is working on Emily Dickinson’s Letters and focuses on the ways Dickinson employed the letter, a means of interpellation, to dodge interpellation as well as on the techniques she uses to set a time and place in a specific document free from its spatiotemporal boundaries. She has translated Dickinson’s Letters in Greek: "Emily Dickinson: Επειδή δεν άντεχα να ζήσω φωναχτά. Ποιήματα και Επιστολές." I could not bear to live aloud. Translation of a selection of Emily Dickinson's Poems and Letters. Athens: Gutenberg Press, 2013.

Sources

Overview

Rutledge, Louis C. “Emily Dickinson’s Arthropods.” AMERICAN ENTOMOLOGIST. Summer 2003, 70-74.

History

Hampshire Gazette, August 26, 1862

Harper’s Monthly, August 1862

Springfield Republican, August 23, 1862

Biography

Dickinson, Susan. “Annals of the Evergreens.” EDA, 2008.

Farr, Judith, with Louise Carter. The Gardens of Emily Dickinson. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2004, 146, 196.

Landry, H. Jordan. “Animal/Insectual/Lesbian Sex: Dickinson’s Queer Vision of the Birds and the Bees.” The Emily Dickinson Journal 9, 2, (Fall 2000): 42-54, 50-51.

Morgan, Victoria. “‘Repairing Everywhere without Design’? Industry, Revery and Relation in Emily Dickinson’s Bee Imagery.” Shaping Belief: Culture, Politics, and Religion in Nineteenth-Century Writing. Eds. Clare Williams and Victoria Morgan. Liverpool: Liverpool University Pres, 2008. 73-93, 84.

Shakleford, Aaron. “Dickinson’s Animals and Anthropomorphism.”

The Emily Dickinson Journal 19, 2 (2010): 47-66, 61.

Perhaps a more revealing intertext for “If you were coming in the fall,” this week’s post on Bowles and Bees, and, more broadly, the circuits and assumptions of desire that charge Dickinson’s social situation at home is Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale.

In Act II, Scene 1, King Leontes’ son Mamillius readies to whisper his ‘winter’s tale’ into his mother Hermione’s ear.

“A sad tale’s best for winter: I have one

Of sprites and goblins.

…

There was a man–

…

Dwelt by a churchyard: I will tell it softly;

Yond crickets shall not hear it.”

Leontes enters the room as he hears from an aide a report that his personal advisor Camillo was seen whispering with Leontes’ childhood best friend Polixenes, who is about to leave on a ship for his journey back home after spending a rollicking good time as the guest of Leontes and Hermione.

During that time, Leontes has come to believe that Polixenes has impregnated his wife with the baby she is about to birth. Leontes has even ordered Camillo to poison Polixenes before he leaves. Now Leontes believes, after hearing of the aide’s account, that Camillo is conspiring with Polixenes to save the fate of the latter.

Maybe, for Dickinson, the theme of ‘separation’ is one component of a larger emotional state of feeling left out of a tight-knit circle of friends and family: brother Austin, sister-in-law Sue, and good friend Samuel Bowles. Is she really pining romantically for Samuel per se, or is he, and his journeys by ship afar, the figures by which she is feeling out her jealousy, confusion, and anger around the cross-currents of attention and intimacy created amongst her and these three others at the Evergreens? As we well know, there is more evidence for Emily’s sexual attraction to Sue than there is for Samuel. Nonetheless, Dickinson’s image of Samuel’s doting, as a bee, on Sue and her son “Jackey” poses Sue’s attraction to Samuel. Where is Austin, Jackey’s actual father, in Dickinson’s sentence to Samuel: “when the writing tires you – play it is Her, and “Jackey” – and that will rest your eyes – for have not the Clovers, names, to the Bees?”

Hermione twice asks her son, the boy prince Mamillius, to sit to tell his story to her ear, for she is tired by the new life stirring in her body. Yet, she asks her son,

“What wisdom stirs amongst you? Come, sir, now

I am for you again

…

and do your best

To fright me with your sprites; you’re powerful at it.”

The power of the storyteller is in the influence they have over the listener. Bowles literally wrote the news of the day, and pulled out poems from his pockets that, submitted to him, he could choose to share with others, or not. ‘Winter’s tales’ of fairies could be mere bobbies for children and women, frivolous news items, or they could be whispered secrets impregnating the hearer with unsurpassed gifts of devotion. For some, those gifts, evocative life forms, could be a little too intense, powerful in their traversals with sprites and goblins. Dickinson, despite Susan being a central reader of and responder to her words, knew that she could be overpowering in her dark summoning powers, socially impolitic even to Susan and her more decorous crowd.

Could she find a place there? Did she want to?

Dickinson waited and looked and listened—thoughts buzzing.

When the length of separation becomes completely uncertain, the point of anxiety is no longer the separation itself (a manageable diagnosis) but the very fact of how close yet unknown one is, being so near a most beloved one (Sue?) and yet feeling so far.

But, now, uncertain of the

length

Of this, that is between,

It goads me, like the

Goblin Bee –

That will not state –

it’s sting.

For what buzzing and what bee is Sue most interested in, and what is the bee to Emily—is it herself, the sting from others, her own sting? How have Austin bee and Samuel bee pollinated Sue in ways that Emily cannot, other than with her words and her looks, in her exchanges within this circle of friends and family?

Mamillius, a child chasing the bee, the “maddest”/“nearest” dream, prefers to feature goblins in the tale he whispers; Dickinson is goaded by the Goblin Bee; as the bee, in its imagistic use throughout Dickinson, tends toward drinking and sipping.

By merely observing the social pleasantries and warmness with each other, drinks in hand, Leontes becomes convinced that Polixenes has surreptitiously impregnated his wife.

“There may be in the cup

A spider steep’d, and one may drink, depart,

And yet partake no venom, for his knowledge

Is not infected: but if one present

The abhorr’d ingredient to his eye, make known

How he hath drunk, he cracks his gorge, his sides,

With violent hefts. I have drunk,

and seen the spider.

“It,” the Goblin/goblet bee, “has stated it’s sting.”

Perhaps Emily wants Samuel back to complete that scene again, and so observe the bees of her garden more directly, drinking and sipping in the parlor rooms, as she sits,

The Bravest – of the Host –

Surrendering – the last –

Nor even of Defeat – aware –

When cancelled by the Frost –

Michael Amico

Researcher, Center for the History of Emotions, Max Planck Institute for Human Development

Berlin

I quote Amico’s sentence here, because THAT is a great question:

“How have Austin bee and Samuel bee pollinated Sue in ways that Emily cannot, other than with her words and her looks, in her exchanges within this circle of friends and family?”

I always felt – being native speaker in a language “Bee” (abelha) is female – that Dickinson plays with gender issues when using Bee. Playing also in the sense of “exchanging roles”. But maybe I see things…

Anyway, this letter is an abyss – and a bliss.

The word “Sould” on the transcription is not “Soul”? And Steamer is the ship, right? I mean, she opens the Springfield Republican and sees the ships all around the world (including the one Bowles travels). Is it?

Thanks.