“Thank you for your surgery”

On April 25th, 1862, Dickinson wrote to Higginson for the second time, apparently after some delay:

Your kindness claimed earlier gratitude – but I was ill – and write today, from my pillow. (L261)

As discussed in last week’s post, Dickinson was first prompted to write after reading Higginson’s essay, “Letter to a Young Contributor,” published in the Atlantic Monthly on April 15th, and her letter inspired a swift response. Though we don’t know exactly what Higginson said in his reply to Dickinson, we do know that he offered some criticism of the poems she enclosed—criticism that she refers to in her second letter as “surgery.” Having her poems dissected by an established male editor “was not so painful as I supposed,” she writes, but she side-steps his advice, engaging on her own terms, in a series of dense, opaque lines, discussed in This Week in Biography.

This scenario is all too familiar to poets who are women. In 1964, Adrienne Rich wrote a poem to Emily Dickinson, referencing Higginson's involvement in and “garbling” of the posthumous publication of Dickinson poetry. The poem's title is a phrase taken directly from Dickinson's June 7th, 1862 letter to Higginson (L265). Check out the pun on “premises” at the end of the poem!

“I am in Danger Sir”

“Half-cracked” to Higginson, living,

afterward famous in garbled versions,

your hoard of dazzling scraps a battlefield,

now your old snood

mothballed at Harvard

and you in your variorum monument

equivocal to the end

who are you?

you, woman, masculine

in single-mindedness,

for whom the word was more

than a symptom

a condition of being.

Till the air buzzing with spoiled language

sang in your ears

of Perjury

and in your half-cracked way you chose

silence for entertainment,

chose to have it out at last

on your own premises.

– Adrienne Rich, from Necessities of Life (1966)

This week’s post explores one of Dickinson’s experiences of receiving literary criticism, underscoring the literary shrewdness and subversive assertions in her reply.

“This hectic grandiloquence so fashionable among the codfish aristocracy”

NATIONAL HISTORY

Springfield Republican, April 26

The Pear and Grape Mania, p. 1:

“Pyrumnia, or pear fever, and vitifermania, or grape fever,” says the New York Horticulturist, are endemic diseases, affecting most violently the inhabitants of anti-rural towns, and chiefly those recently from city life in the spring. This disease, to plethoric purses, is well understood by nurserymen, to whom its appearance is as welcome as an epidemic to young physicians, or a financial crisis to briefless lawyers. The first stage of the disease usually commences soon after taking a country residence, and shows itself in a general admiration of fruit. Soon half a dozen or more thrifty tress and vines are bought. These trees are generally faultless in shape and proportion, and the nurseryman very reluctantly, but obligingly parts with them.

Emancipation and Colonization, p. 2:

Frank P. Blair of Missouri made a speech in Congress, on the 11th, in defense of the president’s war policy, and of his plan of colonizing Black people as they are emancipated.

We can make emancipation acceptable to the whole mass of non-slaveholders at the South by coupling it with the policy of colonization. The very prejudice of race which now makes the non-slaveholders give their aid to hold the slave in bondage will then induce them to unite in a policy which will rid them of the presence of the negroes; and, as nine out of ten of the white people of the South are non-slaveholders, and as the right of suffrage is almost unlimited, it is easy to see what will be the result. It is objected, however, that we have no right to remove the negroes from their own country against their will. I do not believe that compulsory colonization is necessary to the ultimate success of this plan; but neither do I regard it with any abhorrence. On the contrary, I look at it as the greatest boon we can confer upon this race—greater by far than the gift of personal freedom in a land in which they must forever remain in a condition of social inferiority, among people who will treat them with every imaginable indignity.

The Abuse of Words

It may be a small matter to some that the noblest words in the English language are daily prostituted to the commonest affairs of life, but to an admirer of his mother tongue it is certainly painful. The constant application of great words to small things is gradually undermining the native strength of the language, insomuch that to make an impressive statement it is not infrequently necessary to pile a Pelion of adverbs upon an Ossa of adjectives. But that is not the only bad phase of the subject; to plain matter of fact sort of people nothing can be more nauseating than this hectic grandiloquence so fashionable among the codfish aristocracy.

Books, Authors and Art, p. 7:

Mrs. H. B. Stowe’s Romances of Italy and America, “Agnes of Sorrento,” and “The Pearl of Orr’s Island,” will appear in book form on the same day. One is a story of the Old World’s loves and sorrows, and the other is a vivid picture of our own country’s romance of a newer life. Messrs. Ticknor & Fields, in Boston, and Messrs. Sampson, Low & Co., in London, will bring out both these charming stories on the 1st of May. The author of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” thus provides summer reading for both sides of the Atlantic.

Mrs. H. B. Stowe’s Romances of Italy and America, “Agnes of Sorrento,” and “The Pearl of Orr’s Island,” will appear in book form on the same day. One is a story of the Old World’s loves and sorrows, and the other is a vivid picture of our own country’s romance of a newer life. Messrs. Ticknor & Fields, in Boston, and Messrs. Sampson, Low & Co., in London, will bring out both these charming stories on the 1st of May. The author of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” thus provides summer reading for both sides of the Atlantic.

The Unparalleled Flood of 1862, p.8

The rapid melting of immense bodies of snow throughout New England has caused a sudden freshet in most of the rivers, wholly unparalleled at some points. No rain fell until the water had begun to subside. The few warm days of last week caused the snow to melt and run like butter… As the great spring freshet of 1801 was called the “Jefferson flood,” and that of 1854 the “Nebraska flood,” so this unparalleled one of 1862 may perhaps go down to posterity under the name of the “Secession flood.”

Hampshire Gazette, April 29 1862

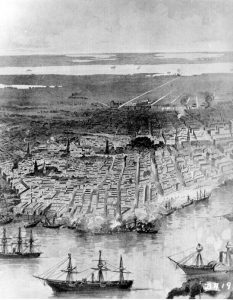

New Orleans Captured, p. 2

Dispatches from Gen. Wool at Fortress Monroe, and Gen. McDowell, at Fredericksburg, contain the intelligence, obtained from rebel newspapers, published in different southern cities, that New Orleans has been captured by the federal forces.

Dispatches from Gen. Wool at Fortress Monroe, and Gen. McDowell, at Fredericksburg, contain the intelligence, obtained from rebel newspapers, published in different southern cities, that New Orleans has been captured by the federal forces.

The correspondent of the Herald, under date of the 23d, states that Fredericksburg, Va., is now occupied by Gen. McDowell’s force. The troops are in excellent health, only 75 being on the sick list, including 14 wounded. The flotilla has succeeded in clearing the Rappahannock of obstructions, and reached Fredericksburg on Saturday. Work has been commenced on the Acqui Creek and Fredericksburg railroad, which will soon be in running order. The railroad bridge over the Rappahannock will of course be immediately rebuilt.

“The Most Experienced and Worldly Coquette”

Upon receiving Dickinson’s first letter, Higginson reported in a reminiscence published after her death that he was struck by

the impression of a wholly new and original poetic genius

exemplified by the four poems she enclosed. Just what Higginson wrote back to Dickinson is up for speculation; even he seems to have forgotten, as he admits in his 1891 recollction in the Atlantic, “On Dickinson’s Letters:”

It was hard to tell what answer was made by me, under these circumstances, to this letter. It is probably that the advisor sought to gain time a little and find out with what strange creature he was dealing. I remember to have ventured on some criticism which she afterward called “surgery,” and on some questions, part of which she evaded, as will be seen, with a naive skill such as the most experienced and worldly coquette might envy.

Indeed, in her letter Dickinson thanks Higginson “for the surgery,” riffing on whatever dissecting remarks he made about her four enclosed poems and the fact that, one line before, she claimed to be ill in bed. Jason Hoope, who studies their relationship, remarks that

these passages expand on the stylistic criterion of vitality established by the first letter

and that Higginson’s criticism

dovetails with the phenomenon of Dickinson’s own physical illness; both her poetry and her person, she suggests, are in a state of recovery from Higginson’s salutary critical procedure—the invasions of editorial “surgery” are appreciated as “kindness.”

In the Atlantic essay written many years after the events, Higginson claims that in her second letter Dickinson attempted to “step nearer, signing her name” and calling him her “friend.” He is also impressed by her astute response to his didacticism:

It will also be noticed that I had sounded her about certain American authors, then much read; and that she knew how to put her own criticism in a very trenchant way.

Dickinson’s lines were trenchant, to say the least, and convey a pointed dishonesty that obscures her intent in responding to, or accepting, Higginson’s criticism, advice, and correspondence.

You speak of Mr. Whitman. I never read his book, but was told that it was disgraceful.

I read Miss Prescott’s Circumstance, but it followed me in the dark, so I avoided her.

Dickinson's demure categorization of Whitman as “disgraceful” leaves us wondering; a poet with her ear to the ground and an appetite for upending literary convention, she very well might have read Leaves of Grass, however disgraceful. As for Harriet Prescott Spofford’s Circumstance, the post for January 8-14 makes the case that several of Dickinson’s poems were directly influenced by what David Cody calls the “Azarian School” named after Spofford’s novel, Azarian. In fact, in a column Susan Dickinson wrote in the Springfield Republican praising Spofford’s works, she reports having sent “Circumstance” to Dickinson, her sister-in-law, after reading it. Dickinson immediately replied:

Dear S. That is the only thing I ever saw in my life that I did not think I could have written myself. You stand nearer the world than I do. Send me everything she writes.

Regardless of what Dickinson is willing to admit to Higginson, it is clear that she was intensely interested in Spofford’s writing. And she clearly read the Azarian works thoroughly; Cody points to a handful of Dickinson’s poems that are intertexts for, or at the very least heavily influenced by, Spofford’s novels.

These are not the letter’s only half-truths. “You ask how old I was?” Dickinson writes, “I made no verse – but one or two – until this winter – Sir –.” This is, of course, blatantly false, as Dickinson had been writing deftly since at least 1858, and had penned hundreds of poems, distributing many to friends and family members before contacting Higginson. She goes on to mischaracterize her status as a novice, asking

I would like to learn – Could you tell me how to grow – or is it unconveyed – like Melody – or Witchcraft?

In asking for Higginson’s guidance and simultaneously likening it to witchcraft, Dickinson belies her claim to being a beginning poet. What could a male magazine editor have to offer to her about the unconveyable art of witchcraft or melody? Further, Hoope argues that Dickinson’s fib stands as a parody of Higginson’s condescension in the Atlantic’s “Letter,” where he said:

Do you know, my dear neophyte, how Balzac used to compose?

Dickinson goes on to relay that she

had a terror – since September – I could tell to none – and so I sing, as the Boy does by the Burying Ground – because I am afraid.

Cynthia Wolff comments that “for a long time critics supposed that this ‘terror’ was some disappointment in love,” but she disagrees:

she scarcely knew Higginson at the time of this letter, and it would be astonishing to find her alluding to such an intimate matter in so early a note.

If Dickinson had been referring to a love affair gone wrong, Wolff thinks she would have said “loss” or “disappointment.” Instead, Wolff asserts, it is more likely that the “terror” refers to “periods of severely impaired vision.”

Additionally, Susan Leiter wonders if Dickinson might be referring to the departure of Rev. Dr. Wadsworth, which made the news that week.

Philadelphia Daily News

The Arch Street Presbyterian Church firmly but kindly resisted the application of the Rev. Dr. Wadsworth for a dissolution of the pastoral relation. So urgent were the people, that the Presbytery sent back the application to the congregation. But when it was found that the Dr. had made up his mind that it was his duty to go to California, the congregation yielded, and he was dismissed. He was accepted to the pastorate of the Calvary Church, San Francisco…

If Dickinson’s meanings in correspondence with Higginson are so obscured and indirect, then what were her intentions? Hoope asserts another possible reading of her letters:

By radically joining herself and her writing to Higginson and his writing, moreover, Dickinson links the antinomian qualities of her charismatic personality to social belonging and poetic achievement. In one movement she thus reverses the alienation and commonness Emerson associates with portfolioists, who are on his account mostly lonely eccentrics who litter the “masses of society,” with the fruits of their inspiration “sacred” to themselves alone.

In exchanging reading lists, asking for literary criticisms but then asserting her own standard, and even commenting on Higginson’s own writing—“I read your Chapters in the Atlantic – and experienced honor for you,” Dickinson engages Higginson in a discourse of two equals, or, as Hoope calls it, a “poetic elect.” Referring to Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of “equality in honor,” Hoope thinks we can understand Dickinson’s “riposte” as a relationship between writers who are both up for the challenge, willing to “play the game.” At any rate, Dickinson’s rhetorical agility and coy rebuttals in her second letter spurred a long correspondence and friendship with Higginson, who would be inspired by her “wholly new and original poetic genius.”

Reflection

Joseph Waring

Scholars have argued for treating Dickinson’s letters, including her letters to Higginson, as literary texts, but rarely are they read for their subversive potential as queer. In light of her decision to sidestep the publishing industry and forgo conventional metrics of “success,” Dickinson wrote with a negative affect that resembles what Jack Halberstam terms a “queer art of failure.”

Scholars have argued for treating Dickinson’s letters, including her letters to Higginson, as literary texts, but rarely are they read for their subversive potential as queer. In light of her decision to sidestep the publishing industry and forgo conventional metrics of “success,” Dickinson wrote with a negative affect that resembles what Jack Halberstam terms a “queer art of failure.”

By negative affect, Halberstam means the “disappointment, disillusionment, and despair” that “poke holes in the toxic positivity of contemporary life” (Halberstam 3). Dickinson’s disillusionment with the publishing industry is well-documented in her verse—“Publication – is the Auction / Of the Mind of Man” (F788, J709)—and her second letter to Higginson invokes an ongoing sense of unnamed despair: “I had a terror since September, I could tell to none; and so I sing, as the boy does by the burying ground, because I am afraid” (L261).

Moreover, in a letter that otherwise might have been a request for literary mentorship, Dickinson insists on invoking illness, pain, and loss while concealing her motives behind a cryptic rhetorical mask. Her letter rejects what Halberstam calls a certain strain of “positive thinking,” a “North American affliction” that traffics in

a combination of “American exceptionalism” and a desire to believe that success happens to good people and failure is just a consequence of a bad attitude (Halberstam 3).

“Are you too deeply occupied to say if my verse is alive?,” Dickinson asks in her first letter, precluding the opportunity for Higginson to say if it’s good or “successful.”

Though scholars portray Higginson as a literary mentor and teacher, Dickinson’s letters verge on a vision of “education” that is anti-disciplinarian, anti-authoritarian, and untrained. First, she deceives Higginson, claiming that she “made no verse, but one or two, until this winter,” which we know to be untrue—a simple lie, but it undermines the teacher-student norm, which requires students to be honest. Second, she asserts herself as unschooled: “I went to school,” she admits, “but in your manner of the phrase had no education.” Instead, she avows an alternative form of education, an unconventional teacher: “When I was a girl, I had a friend who taught me Immortality.” Finally, she mentions past experiences with “tutors” that were rife with conflict. One died, leaving her with one companion, her “lexicon,” and the second “was not contented [that she] be his scholar, so left the land.”

Her misadventures with education and insistence on alternative pedagogy are akin to Halberstam’s “counterintuitive modes of knowing such as failure and stupidity” (11-12). Though no one would ever call Dickinson’s “stupid,” Halberstam invokes a sort of unschooled, subversive naiveté, a

refusal of mastery, a critique of the intuitive connections within capitalism between success and profit, and as a counter hegemonic discourse of losing (12).

“I would like to learn,” Dickinson insists, but she proposes only alternative pedagogies—learning immortality from a child, for example—and suggests that any “growth” might be unconveyed rather than studied, “like melody or witchcraft.” What does witchcraft have to do with education? It is, as Halberstam would call it, a “counter hegemonic discourse,” an alternative way of knowing (12).

In the closing line, Dickinson signs her letter, “Your friend,” as if to recall Ranciére’s The Ignorant Schoolmaster or Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Dickinson rejects the hierarchy of student-teacher relations, and insists on a “two-way street,” a “dialogic relation to the learner” (13). Halberstam comments:

[Ranciére’s book] examines a form of knowledge sharing that detours around the mission of the university, with its masters and students, its expository methods and its standards of excellence, and instead endorses a form of pedagogy that presumes and indeed demands equality rather than hierarchy.

Now, to zero in on the second letter’s most peculiar, and perhaps queer, diction. “Thank you for the surgery,” Dickinson writes, “it was not so painful as I supposed.” Why use a term like “surgery” to describe Higginson’s critique of her poetry? Why subject herself to his pen at all? Halberstam, verging on the Freudian, argues that “cutting”—where Dickinson’s “surgery” stands in as a textual metaphor for self-harm—

is a feminist aesthetic proper to the project of unbecoming (135).

Writing to Higginson, knowing well the pain it might entail, is Dickinson’s form of “unbecoming,” implicating a “desire for mastery, and an externalization of erotic energy” (135). In two moves—exposing herself to critique and then undermining it—Dickinson shatters the hegemonic “self” of the conventional poet, a practice that “may have its political equivalent in an anarchic refusal of coherence and proscriptive forms of agency.” Out of the public eye and away from the editor’s pen, Dickinson remains illegible to the hegemonic powers that be. Her “surgery” is the cut that breaks her away through a “masochistic will to eradicate the body” and leave only the page (135):

The antisocial dictates an unbecoming, a cleaving to that which seems to shame or annihilate, and a radical passivity allows for the inhabiting of femininity with a difference. The radical understandings of passivity … offer an antisocial way out of the double bind of becoming woman and thereby propping up the dominance of man within a gender binary (144).

What is queer about all this? Dickinson forgoes hegemonic structures, engages in self-shattering, revels in illegibility, and embraces the

incoherent, the lonely, the defeated, and the melancholic formulations of selfhood that it sets in motion (148).

If, at one time, her only companion was her lexicon, then that is a “lexicon of power” that, as Halberstam maintains, “speaks another language of refusal” (139).

Sources

Halberstam, Jack. The Queer Art of Failure. Durham: Duke University Press, 2011.

Bio: Joe Waring graduated from Dartmouth College, where he studied English, Italian, and Linguistics. He came by Dickinson like most, in his high school classroom, where he memorized “It Feels A Shame To Be Alive,” and was happy to revisit Dickinson in Professor Schweitzer's class, “The New Emily Dickinson: After The Digital Turn.” His favorite Dickinson poem is, unquestionably, “The Mushroom is the Elf of Plants” (F1350, J1298).

Sources

Overview

Higginson, Thomas Wentworth. “Emily Dickinson’s Letters,” The Atlantic, October 1891.

Rich, Adrienne. Necessities of Life. New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1966.

History

Hampshire Gazette, April 29 1862

Springfield Republican, April 26 1862

Biography

Dickinson, Susan Huntington. “Harriet Prescott’s Early Work: A Reader Who Agrees with Us That Mrs. Spofford Should Republish.” Springfield Republican. 1 February 1902: 19.

Leiter, Sharon. Critical Companion to Emily Dickinson: A Literary Reference to Her Life and Work. New York, NY: Facts on File, 2007. Print

Hoppe, Jason. “Personality and Poetic Election in the Preceptual Relationship of Emily Dickinson and Thomas Wentworth Higginson, 1862-1886.” Texas Studies in Literature and Language, vol. 55 no. 3, 2013, pp. 348-387, 352-58. Project MUSE, muse.jhu.edu/article/517590.

Higginson, Thomas Wentworth. “Emily Dickinson’s Letters.” Atlantic Monthly, October 1891.

Wolff, Cynthia. Emily Dickinson. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co., Inc. 1988, 165.