July 1, 1862 marked the 6th wedding anniversary of Susan and Austin Dickinson, sister-in-law and older brother of Emily Dickinson. It spurs this week’s exploration of the important theme of marriage in Dickinson’s work. We also take inspiration from the publication in this month’s Atlantic Monthly of Julia Ward Howe’s tonally ambiguous poem, “The Wedding,” the second in her series titled Lyrics of the Street, reproduced in “This Week in History.”

July 1, 1862 marked the 6th wedding anniversary of Susan and Austin Dickinson, sister-in-law and older brother of Emily Dickinson. It spurs this week’s exploration of the important theme of marriage in Dickinson’s work. We also take inspiration from the publication in this month’s Atlantic Monthly of Julia Ward Howe’s tonally ambiguous poem, “The Wedding,” the second in her series titled Lyrics of the Street, reproduced in “This Week in History.”

For a woman of Dickinson’s time, region, and class, marriage was the acme of a female life. Such women were not considered “complete” without it. In 1966, historian Barbara Welter described what she called “the cult of domesticity” or “cult of true womanhood,” a set of ideas purveyed by sermons, how-to books and women’s magazines for middle and upper-class white Protestant New-Englanders, in response to a range of social developments: the disappearance of the family farm, where everyone worked together; new professions located outside the home; and the flood of immigrants crowding cities and even small towns like Amherst, MA. She titled her book on the subject, Dimity Convictions: The American Woman in the Nineteenth Century. She takes her opening phrase from a line in Dickinson's poem, “What soft – Cherubic Creatures–/These Gentlewomen are –" (F675), which condemns the timidity of the women of Dickinson's class.

At the same time, in legal terms, when a woman married, she moved from the legal category of feme sole (single woman) to the legal category of feme coverte (covered or protected woman), where her identity merged with that of her husband and she, essentially, had no rights apart from his protection. Reform of these laws in the form of the Married Women’s Property Acts began in the mid-nineteenth century but was not fully accomplished nation-wide until the early twentieth-century.

This vision of femininity reflected what scholars identified as an ideology of “separate spheres” for men and women, based on biologically determined gender roles and part of a complex system of “sex-gender conventions” that prevailed in the northeast US in the 19th century. It rested on four central “virtues:” piety, purity, domesticity and submissiveness. Recently, historians have challenged and amplified Welter’s definition. For example, Susan Cruea identifies four evolving and overlapping images of women in the nineteenth century: not only True Womanhood, but Real Womanhood, Public Womanhood and New Womanhood.

While the reality and effect of the beliefs in True Womanhood are palpable in Dickinson’s circle, as we will see in the poems for this week, there were also palpable tensions in this ideology and strong resistance to it. In her poem, “The Wedding” published in July 1862, for example, Julia Ward Howe called marriage “the weighty yoke / Might of mortal never broke!” and characterized the “the wedded task of life” as “Mending husband, moulding wife.”

A salient site of Dickinson’s desire and resistance to this ideology is her extensive series of poems that explore marriage in all its dimensions, often highly metaphorical and “mystical.” These poems explore betrothal, the bride and bridegroom, the wedding and its aftermath of consummation, the wife’s experience and entitlement, and the frequent renunciation that accompanies love and marriage. Although Dickinson never married, she had several proposals, one as late as 1882 from Judge Otis Lord when she was in her early 50s. Some scholars read her marriage poems biographically, but we will approach them as complex explorations of female identity. For models, Dickinson could draw on several very different types of marriages among her circle of intimates. We will look at these marriages, the current attitude towards marriage in the press, and Dickinson’s extraordinary poetry of marriage.

“They Will All Have to Die Old Maids”

Springfield Republican, July 5

Progress of the War, page 1

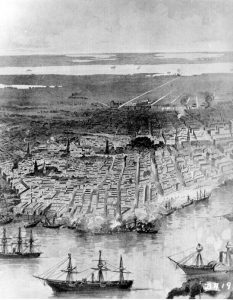

“We are in the midst of the great struggle before Richmond, with only imperfect accounts of the events that occurred last week. The prominent and most important fact is that Gen. McClellan has changed his entire line in the face of the enemy, and while a severe battle was raging, and that his army now occupies the region between the Chickahominy and James river, that his base of operations at the White House landing is abandoned and his supplies and reinforcements now go up the James River. A series of great battles has been fought commencing on Wednesday of last week and continuing until Sunday, possibly until the present hour, and there is no reason to expect a further lull in the storm till the fate of Richmond and of the rebel armies that defend it is decided.”

From Washington, page 1

“No one can think of anything but the great battle at Richmond and the gigantic movements of the last few days. Is McClellan whipped? Is our army in danger of immediate destruction? Can McClellan still evolve victory from apparent disorder? Great battles have been fought—and the war department pretends it has no news.”

Poetry, page 5

General News, page 5

“English antiquarians are much exercised over the identity of a human skeleton just discovered at Leicester. It is supposed that the remains are those of King Richard III.”

“The reason the southern women are so bitter in this rebellion, against the people of the North, is that the southern men prefer the northern women to them, and they are afraid if the war ceases they will all have to die old maids.”

Wit and Wisdom, page 6

“Some married folks keep their love, like their jewelry, for the world’s eyes; thinking it too precious for everyday wear at the fireside.”

“Men love women for their natures—not their accomplishments. More men of genius marry, and are happy, with women of very common-place understandings, than ever venture to take brilliant wives, and enjoy a showy misery.”

The First Death, page 7

“It is wonderful how a war like this ennobles death. Once it was only sad to think of the first death, and no subsequent bereavement seemed quite like that. The heart was not accustomed to chastening when the first blow fell, nor the home used to such visitants when the destroying angel first crossed its threshold. That house of mourning may become again a house of feasting, but the memory of the darkened chamber and vacant chair below survive all change.”

Books, Authors and Art, page 7

“There are certain books which are not what we wish they were, because we are confident they are not what their authors are capable of producing—books of promise—books which betray a nature kept by circumstances from a free and full development—books which impress without satisfying—books which please moderately, yet yield us no full throb of pleasure—books with musical threats and warm bosoms and fine plumage, but no wings, no faculty of flight to take us up through the ether. One of these books is “Home, and other Poems” by A.H. Caughey of Erie, PA.”

Woman and Chivalry, page 7

“A man should yield everything to a woman for a word, for a smile—to one look of entreaty. But if there be no look of entreaty, no word, no smile, I do not see that he is called upon to yield much.”

Atlantic Monthly, July 15

Originality, page 63

“A great contemporary writer, so I am told, regards originality as much rarer than is commonly supposed. But, on the contrary, is it not far more frequent than is commonly supposed? For one should not identify originality with mere primacy of conception or utterance, as if a thought could be original but once. In truth, it may be so thousands or millions of times.”

Lyrics of the Street II [from a series of 6], page 98

“The Wedding” by Julia Ward Howe

In her satin gown so fine

Trips the bride within the shrine.

Waits the street to see her pass,

Like a vision in a glass.

Roses crown her peerless head:

Keep your lilies for the dead!Something of the light without

Enters with her, veiled about;

Sunbeams, hiding in her hair,

Please themselves with silken wear;

Shadows point to what shall be

In the dim futurity.Wreathe with flowers the weighty yoke

Might of mortal never broke!

From the altar of her vows

To the grave’s unsightly house

Measured is the path, and made;

All the work is planned and paid.As a girl, with ready smile,

Where shall rise some ponderous pile,

On the chosen, festal day,

Turns the initial sod away,

So the bride with fingers frail

Founds a temple of a jail,—Or a palace, it may be

Flooded full with luxury,

Open yet to the deadliest things,

And the Midnight Angel’s wings.

Keep its chambers purged with prayer:

Faith can guard it, Love is rare.Organ, sound thy wedding-tunes!

Priest, recite thy wedding tunes!

Hast no ghostly help nor art

Can enrich a selfish heart,

Blessing bind ‘twixt greed and gold,

Joy with bloom for bargain sold?Hail, the wedded task of life!

Mending husband, moulding wife.

Hope brings labor, labor peace;

Wisdom ripens, goods increase;

Triumph crowns the sainted head,

And our lilies wait the dead.

Reviews and Literary Notices, page 124

“‘Fantine,’ the first of five novels under the general title of ‘Les Misérables,’ has produced an impression all over Europe, and we already hear of nine translations. It has evidently been ‘engineered’ with immense energy by the French publisher. Every resource of bookselling ingenuity has been exhausted in order to make every human being who can read think that the salvation of his body and soul depends on his reading ‘Les Misérables.’”

“That Great Blessedness”

Dickinson’s feelings about marriage emerge early in her writing. In a letter to Susan Gilbert, dated early June 1852, Dickinson recalls a walk with her friend Mattie, how they talked about “life and love, whispered our childish fancies about such blissful things” and

wondered if that great blessedness which may be our’s sometime, is granted now, to some. Those unions, my dear Susie, by which two lives are one, this sweet and strange adoption wherein we can but look, and are not yet admitted, how it can fill the heart, and make it gang wildly, beating, how it will take us one day, and make us all it’s own, and we shall not run away from it, but lie still and be happy.

It is not clear whether Dickinson refers here to heterosexual marriage or, as some commentators argue, a great love she feels for Sue. What is clear is that she is looking at this rapturous state from the outside and has some fear of it. The phrase, “but lie still and be happy,” echoes the advice about unwanted marital sex purportedly given to women at the time, sometimes attributed to Queen Victoria: “close your eyes and think of England.” Women were not supposed to have or feel or own up to sexual desires.

Dickinson goes on in the letter to chide Susan for being “strangely silent on this subject,” asks her if she has a “dear fancy, illuminating all your life … one of whom you murmured in the faithful ear of night,” and insists

when you come home, Susie, we must speak of these things. How dull our lives must seem to the bride, and the plighted maiden, whose days are fed with gold, and who gathers pearls every evening; but to the wife, Susie, sometimes the wife forgotten, our lives perhaps seem dearer than all others in the world; you have seen flowers at morning, satisfied with the dew, and those same flowers at noon with their heads bowed in anguish before the mighty sun; think you these thirsty blossoms will now need naught but – dew? No, they will cry for the sunlight, and pine for the burning noon, tho’ it scorches them, scathes them; they have got through with peace – they know that the man of noon, is mightier than the morning and their life is henceforth to him. Oh, Susie, it is dangerous and it is all too dear, these simple trusting spirits, and the spirits mightier, which we cannot resist! It does so rend me, Susie, the thought of it when it comes, that I tremble lest at sometime I, too, am yielded up. (L93; her emphasis).

From this “amatory strain,” we can draw several inferences about Dickinson's feelings about marraige. On the one hand, Dickinson feels that non- or pre-brides and “unplighted” maidens have dull lives, although the phrases describing brides as “fed with gold,” and gathering “pearls every evening” verge on the melodramatic and ironic. On the other hand, “the wife forgotten” is pitiful, and the scorching of delicate female flowers by burning “men of noon” is dangerous and threatens to consume women. Dickinson fears being “yielded up,” a doubling of the passive construction.

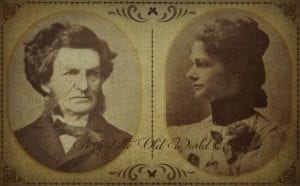

We know that Susan also feared marriage and put hers to Austin off for several years, mainly because of her fear of the sexual component and possibly dying in childbirth. There is speculation that she had several abortions before her first child was born in June 1861, and that she may have tried to terminate that pregnancy as well. This resistance occurred, perhaps, because, by all accounts, her marriage to Austin was miserable. While Susan was a close school friend of Dickinson and was, at first, adored by the Dickinson family, she and Austin had very different expectations of their union. From a less stable background, Sue wanted financial security and improved status. Austin, by contrast, had a romantic streak and craved affection he did not get from his stern father and distant mother.

Although they eventually had three children together, Austin felt exiled from the family and spent much time at the Homestead next door with his two unmarried sisters. Unable to divorce Susan, Austin eventually began a passionate, long-term affair with Mabel Loomis Todd, a much younger woman.

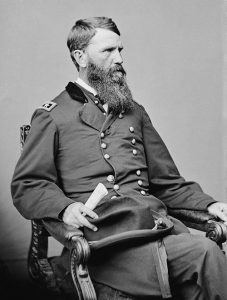

Dickinson’s biography contains several types of marriages that might have colored her feelings about the state. Her parents’ marriage was steadfast but featured a controlling husband who exacerbated the fears and dependencies of his much frailer wife. Austin’s marriage to Susan was a dismal failure that caused much pain to all involved. By contrast, Austin’s lover Mabel was married to David Todd, a young professor of Astronomy, who joined the faculty at Amherst College in 1881, and who seems to have known about and even approved of (and participated in) his wife’s liaison—offering a very different model of an “open” marriage from the very “closed” Victorian model advocated by the reigning sex-gender conventions. A happier version of this ideal was epitomized by Elizabeth and Josiah Holland, friends of Dickinson discussed in last week’s post. As we noted there, Josiah was large, imposing, and intellectual and Elizabeth was small, doting, and warm-hearted. He had a public profile as a writer, lecturer and literary editor of the Springfield Republican while she maintained their busy and vibrant home. Theirs was a traditional marriage that seemed to work incredibly well.

Reflection

Lisa Furmanski

How to Be Wife at the End of the World

How to Be Wife at the End of the World

Inside me is a scarlet feather, clenched

With gauze, it takes my mind abroad

Where I risk the end of our children.

Wed me not to bells, clanging knots,

Their sound is an eclipse of the spirit

Doming a lead gown. I can protest

A bare sun but no way to bear its melt,

Thus I am alone, that is, being a bride.

Night rites blue and our bed plumbs

What the radio said about loneliness.

Wife weeps. Wife pulls at her feather.

Fierce, a woman with such tiny wrists.

I am dogged enough to choir, to carry

Signposts, memes of sickness and vow.

— June 30th, 2018, the day of the March for Families, was unbearable in many ways. The incredible heat was ominous, and the speakers invoked the long, long arc of resistance, nothing near or soon. Is my marriage and wifehood in these times beyond the political, or can it strike a chord of protest? Proof and risk, defiance and intimacy, I want my shared life to be all of these. The poems for this week’s blog, like much of Dickinson’s work that I depend on, are a “puzzle”: of faith and nature and relationships, and inspired this attempt to speak as a wife in these terrible times.

bio: Lisa Furmanski is a physician and writer living in New Hampshire. Her poetry has appeared in Poetry, Gettysburg Review, Antioch Review, Hunger Mountain, Prairie Schooner and elsewhere.

Sources:

Overview

Cruea, Susan. “Changing Ideals of Womanhood During the Nineteenth-Century Woman Movement.” ATQ: 19th century American Literature and Culture. Vol. 19, Issue 3, 2005: 187-204; General Studies Writing Faculty Publications. 1. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/gsw_pub/1

Gerdes, Kirsten. “Marriage and Property Rights.” All Things Dickinson: An Encyclopedia of Emily Dickinson’s World. Ed. Wendy Martin. 2 vols. Greenwood Press, 2014, 564-68.

Welter, Barbara. “The Cult of True Womanhood: 1820-1860.” American Quarterly 18 (2, 1966): 151-74.

As complication and challenge, see:

Davidson, Cathy and Jessamyn Hatcher, eds. No More Separate Spheres!: A Next Wave American Studies Reader. Durham: Duke University Press, 2002.

History

Atlantic Monthly, July 15, 1862.

Springfield Republican, July 5, 1862.

Biography

Dickinson, Emily. The Letters of Emily Dickinson. Eds. Thomas Johnson and Theodora Ward. 3 vols. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1958.

Sewall, Richard. The Life of Emily Dickinson. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1980, 186-96.

Longsworth, Polly. Austin and Mabel: The Amherst Affair and Love Letters of Austin Dickinson and Mabel Loomis Todd. New York: Farrar, Straus, & Giroux, 1983.