On Choosing the Poems

Dickinson described her schooling at Amherst Academy and Mount Holyoke Female Seminary in detailed letters she wrote to friends and her brother Austin during the 1840’s when she attended these schools, but not very much afterwards, and only indirectly in her poetry. Although it’s not clear whether she felt loss at not attending the Seminary for a second year, she was relieved to return to her family and her father’s house, which she then rarely left until her death. In the Dickinsons’ extensive library and varied subscriptions to newspapers and journals, she said that she found “a feast in the reading line” as well as ample time to read, which was seriously curtailed at Mount Holyoke. In Amherst, she also had access to a wealth of scholars, lecturers, eminent visitors and friends of the family to enrich and challenge her mind and imagination.

The poems we have selected for this week illustrate Dickinson’s attitude to “school” in the abstract, to students and their tribulations (often metaphorical), to her dislike of conformity, which was a hallmark of her experience at Mount Holyoke Female Seminary, to the pleasures of reading, which were sublime for her, and that refer to and make use of the learning she did at both of the institutions she attended.

Read – Sweet – how others strove (F323, J260)

Read – Sweet – how others – strove –

Till we – are stouter –

What they – renounced –

Till we – are less afraid –

How many times they – bore

the faithful witness –

Till we – are helped –

As if a Kingdom – cared!

Read then – of faith –

That shone above the fagot –

Clear strains of Hymn

The River could not drown –

Brave names of Men –

And Celestial Women –

Passed out – of Record

Into – Renown!

EDA manuscript: Originally in Poems: Packet XXIII, Fascicle 13-13 (part), Houghton Library – (127c). Includes 11 poems, written in ink, dated ca. 1861. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. First published in Poems (1890), 32, as two eight-line stanzas.

Dickinson copied this poem into Fascicle 13 in the 13th place. It is about the power of reading to recuperate and actually reshape the reader’s mind and temperament, making us “stouter,” “less afraid,” and “helping us.” But the last line of the first stanza seems to question whether this effect matters: “As if a Kingdom – cared!” Still, we wonder who were the “celestial women” Dickinson was reading about who so filled her mind?

Perhaps at issue is the subject of the reader’s attention: those historical figures who “bore the faithful witness.” Their descriptions in the second stanza echo poems like

Through the strait pass of suffering -

The Martyrs – even – trod.

Their feet – opon Temptation -

Their faces – opon God – (F187B, J 792)

And “Unto like Story – Trouble has enticed me –” (F300, J295), which invokes martyrdom through “scaffolds” and “dungeons” and celebrates that “Feet, small as mine – have marched in Revolution …”

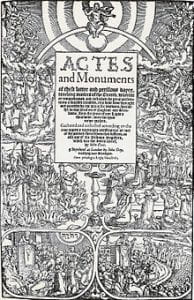

A source for this imagery may be found in John Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, originally published in 1563 and lavishly illustrated with woodcuts that told stories of English Protestants martyred for their beliefs. Dickinson’s family owned a copy of it, which Dickinson loved to read and reread. We could say this poem, with its allusion to this book, gives evidence of a self-made “curriculum about faith” that Dickinson created for herself and pursued through reading. It also affirms the profound effect the act of reading and re-reading had on a sensitive mind like Dickinson’s.

One and One – are One – (F497, J769)

One and One – are One –

Two – be finished using –

Well enough for schools –

But for minor Choosing –

Life – just – Or Death –

Or the Everlasting –

+More – would be too vast

For the Soul's Comprising –

+Two

EDA manuscript: Originally in Poems: Packet XXXI, Fascicle 23-19, Houghton Library – (170b,c). Includes 20 poems, written in ink, ca. 1862. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. First published in Bolts of Melody (1945), 93-94, from a transcript of B (a tr55).

Dickinson copied this poem into Fascicle 23 in the 19th place sometime in late 1862. This gnomic poem begins by rejecting the basic mathematical reasoning taught in school, that 1+1 = 2. Dickinson’s speaker contravenes this knowledge, the production of twoness or duality, by implying that now that we are “finished” with school, we can see the inaccuracy of such reasoning, and move beyond it and the limited framework of thinking it constitutes. The speaker calls it a form of “minor Choosing,” though the syntax here creates multiple references for this comment. Ashok Karra observes the mobility of Dickinson’s diction:

Socrates in the Phaedo: the unity of body and soul is the problem of how 1 + 1 = 1. One is finished using 2 after school is done. Dickinson says “Schools:” it brings to mind the condemnation of the Scholastics common in thinkers from Descartes to Kant. A “School” can even be one of fish.

The second stanza illuminates the speaker’s frame of reference: “Life – just – Or Death – / Or the Everlasting –.” These large and abstract concepts are as much as the “soul” can comprise. Though the variant of “Two” for “More” seems to imply that they are all “ones,” the same, not two or dual. This poem, with its metaphysical speculation, seems to put us in a “School’s out forever” state of mind.

Source

Karra, Ashok. “Emily Dickinson, ‘One and One – are One’ (769).” Rethink. August, 2011.

Much Madness is divinest Sense – (F620A, J435)

Much Madness is divinest Sense –

To a discerning Eye –

Much Sense – the starkest

Madness –

'Tis the Majority

In this, as all, prevail –

Assent – and you are sane –

Demur – you're straightway dangerous –

And handled with a Chain –

EDA manuscript: Poems: Packet XXVIII, Fascicle 29-11, Houghton Library – (151c,d). Includes 20 poems, written in ink, dated ca. 1862. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. First published in Unpublished Poems (1935), 7, as two eight-line stanzas, with the alternative for line 1 adopted.

Dickinson copied this poem into Fascicle 29 in the second half of 1863 in the 11th place, though Thomas Johnson dates it to 1862. Helen Vendler reads it as an angry poem about “the savagery” of the majority and its imposition of conformity on the minority. The terms Dickinson uses are extreme: the majority condemns as “madness” any form of deviance from its strict norms, even the politest “demurral,” which, as Vendler notes, “is the mildest word of opposition.” Demur from the norm and one becomes “dangerous,” a threat to the social order, “and handled with a Chain,” a chilling phrase that evokes not just social ostracism but horrifying mental asylums and medieval dungeons. Yet, to “a discerning eye,” this madness is not just sense, it is “divinest Sense,” the wisdom of the gods.

For Sharon Leiter, this poem

belongs to that group of watershed poems, written during the same prolific period [of 1862-63] including “I’m ceded – I’ve stopped being Theirs –” [F353A, J508] and “On a Columnar Self –” [F740A, J789] in which [Dickinson] finds the strength to declare her independence from both the conventional aesthetic tastes and religious persuasions of her time.

This is certainly possible, but those poems are declarations, while this one is more a critique of the reality of social coercion. To what extent might Dickinson have drawn on her experiences at Mount Holyoke Female Seminary for this poem, a place where she experienced a season of pressure from many sides while away from the comfort and confirmation of home (neither Austin nor her father had converted at the time). The line “Assent – and you are sane –” captures the seductive ease of conversion and social acceptance that Dickinson could not embrace with integrity.

Sources

Leiter, Sharon. Critical Companion to Emily Dickinson: A Literary Reference to her Life and Work. New York: Facts on File, 2007, 143-44.

Vendler, Helen. Dickinson: Selected Poems and Commentaries. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University, 2010, 272-74.

Unto my books so good to turn (F512, J602)

Unto my Books – so good

to turn –

Far ends of tired Days –

It half endears the Abstinence –

And Pain – + is missed – in Praise.

As Flavors – cheer Retarded

Guests

With Banquettings to be –

So Spices – stimulate the time

Till my small Library –

It may be Wilderness – without –

Far feet of failing Men –

But Holiday – excludes the night –

And it is Bells – within –

I thank these Kinsmen of the Shelf –

Their Countenances Kid

Enamor – in Prospective –

And satisfy – obtained –

+ Forgets

EDA manuscript: Originally in Poems: Loose sheets. Various poems. MS Am 1118.3 (383), Houghton Library – (383c). Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. First published in Poems (1891), 74, with the alternatives not adopted.

Written in the common meter of 8686 but with very few rhymes, this poem exemplifies Dickinson’s love of books. We include it to illustrate her self-created curriculum of reading, which she followed all her life.

The speaker describes turning to books at the end of a day of chores, where the time away from reading makes the activity even more pleasurable. The word “Abstinence” suggests a religious or moral forbearance or restriction of appetite or indulgence, close to temperance or celibacy. But the major comparison in the poem is to the pleasure of food (“flavor,” “spices”), as a “retarded [hindered] Guest” coming late to a banquet has their anticipation of the feast whet their appetite. Hunger is a recurrent theme in Dickinson’s work, often figuring a desire for many worldly experiences (see “I had been hungry all the years” [F439A, J579]).

The third stanza can be an allusion to the Civil War, a “wilderness” of “falling Men” outside, while in the room where the speaker reads, bells ring out happily, announcing a holiday. The speaker is well aware of the refuge books provide from the cruelty and sadness of her historical moment.

In a chapter of his biography of Dickinson titled “Books and Reading,” Richard Sewall frames his account with a comment Dickinson made to Joseph Lyman about her eye problems in 1864-65:

Some years ago I had a woe, the only one that ever made me tremble. It was a shutting out of all the dearest ones of time, the strongest friends of the soul – BOOKS. (Lyman letter 4)

In a life filled with losses and disappointments, Dickinson found that books, those “Kinsmen of the Shelf,” would never disappoint her, and the language she uses is one of love: they “Enamor – in Prospective,” that is, thinking about reading makes us fall in love with books, and in the experience of reading we always “obtain” satisfaction. For other poems on books, see “A precious – mouldering pleasure – ‘tis” (F569, J371, 1863) and “There is no Frigate like a Book” (F1286B, J1263, 1873).

Source

Sewall, Richard. The Life of Emily Dickinson. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1980, 668-705.

Tis one by one the Father counts (F646, J545)

'Tis One by One – the Father

counts –

And then a Tract between

Set Cypherless – to teach

the Eye

The Value of it's Ten –

Until the peevish Student

Acquire the Quick of Skill –

Then Numerals are dowered

back –

Adorning all the Rule –

'Tis mostly Slate and Pencil –

And Darkness on the School

Distracts the Children's fingers –

Still the Eternal Rule

Regards least Cypherer

alike

With Leader of the Band –

And every separate Urchin's

Sum –

Is fashioned for his hand –

EDA manuscript: Originally in Poems: Packet XIII, Mixed Fasciles, Houghton Library – (67b). Includes 27 poems, written in ink, ca. 1862. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. First published in Bolts of Melody (1945), 93, from a transcript of A (a tr441), with the alternative adopted.

Dickinson copied this poem into Fascicle 31 in the 17th position around the end of 1863. Johnson dates it to 1862. In this rather somber poem, Dickinson uses the schoolroom and its iconic scene of instruction in arithmetic as an analogy for several divine scenarios: God the Father’s counting the saved and/or his instruction of each individual soul, even “the Least Cypherer,” according to its specific needs.

In the first stanza, the Father counts one [soul] then another, with an empty “tract” between them that is “Cypherless,” a resonant term that can mean several things: beyond or outside human arithmetic and calculation, or disguised and unknowable, since a “cypher,” according to Dickinson’s Webster’s is also the key to a secret code or protected form of writing, as used in wartime (which was the historical context of Dickinson’s poem) to communicate without enemy knowledge. Is the tract a wilderness devoid of saved souls, the blank of failure? In that sense, does it teach us to see the “ten good men” Abraham pleaded with God to save when He threatened to destroy the impenitent cities of Sodom and Gomorrah (Genesis 18-19)? Or is “the Value of it’s Ten” a reference to the power of zero, which added to one makes ten, a possible reference to nothingness or lack of value and another meaning of “cipher”?

The analogy is reinforced in the second stanza’s description of the “peevish Student” finally acquiring “the Quick of Skill.” This phrase can refer to a facility in arithmetic but the word “Quick” also means lively or alive, as in the “quickening” of a fetus in the womb, and could refer to immortality, the truculent student’s ability, finally, to decipher the mind of God with respect to salvation. The next stanza’s reference to “the Eternal Rule” furthers this reading, alluding to a “rule” that explains divine arithmetic and sums up each “Urchin” or soul individually.

Dickinson’s depiction of the schoolroom is dour and dreary, perhaps based on her primary school:

'Tis mostly Slate and Pencil –

And Darkness on the School

Distracts the Children's fingers –

One can almost hear the scratching of pencils (often made of soapstone) on the slates each child would bring to school, a technology that explains why memorization was so important in 19th century schooling. Students did not take notes or do lessons on paper, which was expensive and not reusable, but wrote on inexpensive slates which they erased between each lesson. What is the darkness that has descended on the school and distracts the children from their lessons? If this is a depiction of God’s divine instruction, it is not a cheery one.

Let us play yesterday (F754, J728)

Let Us play Yesterday –

I – the Girl at School –

You – and Eternity – the

untold Tale –

Easing my famine

At my Lexicon –

Logarithm – had I – for Drink –

'Twas a dry Wine –

Somewhat different – must be –

Dreams tint the Sleep –

Cunning Reds of Morning

Make the Blind – leap –

Still at the Egg-life –

Chafing the Shell –

When you troubled the Ellipse –

And the Bird fell –

Manacles be dim – they say –

To the new Free –

Liberty – commoner –

Never could – to me –

EDA manuscript: Poems: Packet XVIII, Fascicle 36, Houghton Library – (102b). Includes 22 poems, written in ink, dated ca. 1863. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge. MA. First published in Unpublished Poems (1935), 105-6, as nine quatrains.

In the second half of 1863, Dickinson copied this poem into Fascicle 36 in the 21st position and though both Franklin and Johnson date it to 1863, we include it because it brings together some of the images and themes from the previous poems in this cluster about schooling.

The speaker opens by suggesting a game to her interlocutor, who may be God or Death, because he is paired with “Eternity.” She will play the role of “the Girl at School,” a youthful scholar eager for knowledge, “Easing my famine/ At my Lexicon.” This image reminds us of Dickinson’s attachment to her Webster’s Dictionary and the nourishing “feasts” of words she found there. One of them was probably “Logarithm.” According to her Webster’s,

logarithms are the exponents of a series of powers and roots. … They are extremely useful in abridging the labor of trigonometrical calculations.

The reference to higher math like trigonometry echoes the divine Cyphering in “Tis one by one the Father counts” discussed above. Dickinson’s Lexicon notes the “word play on ‘logos’ + ‘rhythm’ or ‘rhyme,’” which connects this word to the production of poetry.

The next stanzas offer a difficult-to-parse meditation on the opposition of freedom and captivity through images of bird flight and punishment that echoes the opening of the third Master Document:

If you saw a bullet hit a Bird – and he told you he was'nt shot – you might weep at his courtesy, but you would certainly doubt his word. (L 233)

These stanzas depict birds edging out of eggshells, as schoolgirls edge into maturity, then falling out of the sky; larks trying to get back into their eggs; bonds and manacles, dungeons and questions about how much worse restriction feels to someone who has experienced freedom, someone “doomed new.” The final stanza pleads with the “God of the manacle / As of the free” not to limit the speaker’s “Liberty.” These manacles echo the mental captivity of “Much madness is divinest sense” but are more directly connected to the norming atmosphere of school. Could Dickinson be making a case for not going back to the restrictive conditions of “yesterday” at one of the academic institutions she attended?