On Choosing the Poems

As we described in the post’s introduction, the word white and its cognates appear in many poems, but we have confined our choices to poems written in 1862; they are among Dickinson’s most important work on this theme.

The critical conversation about Dickinson and whiteness has been particularly contentious. For example, in 2000, two prominent Dickinson scholars published essays on the subject in The Emily Dickinson Journal: Vivian Pollak, “Dickinson and the Poetics of Whiteness” and Domhnall Mitchell, “Northern Lights: Class, Color, Culture and Emily Dickinson.” Both locate Dickinson’s representations emerging out of broad cultural changes involving white middle and upper class people looking for ways to distinguish themselves from the lower classes, from social mobility, from aristocratic excess, and from racial and ethnic groups. American Studies scholars have produced important work on this period that details the re-consolidation of whiteness: Toni Morrison, Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination (1992); Eric Lott, Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class (1992); and David R. Roediger, The Wages of Whiteness: Race and the Making of the American Working Class (1999), to name a few.

Mitchell routes his argument through Dickinson’s response to a concert by Jenny Lind, a Swedish soprano, who represented her class’s elevation of all things Northern as culturally superior.

In Mitchell’s mind, whiteness becomes

an agent of social discrimination, a determinant of virtue and value against vulgarity and excess,

a sign of Dickinson’s

strategic disengagement, precisely because it promotes non-specificity, purity of reference, puzzlement, contemplation, inaction.

Pollak argues, more broadly, that

Whiteness functions as an ambivalent sign of historical privilege; the poet … is ambivalent about her whiteness.

But Pollak also claims that Dickinson

identifies her psychological difference from other people with racial and ethnic others,

and that her poems using white imagery clear space “for rebellion against ethnic and racial sexual prejudice” as well as gender non-conformity.

In a 2002 essay, Paula Bennett takes issue with Pollak’s view in particular, and with the majority of critics who view Dickinson outside and above the raft of other women writers of her time, critics who do not call out what Bennett sees as the “racism” in various poems and letters by Dickinson about Irish and African American domestics. It is unrealistic to think that Dickinson, as a product of her culture, was not deeply affected by “the nineteenth century’s racist environment,” including racially insensitive “squibs” and stereotypes penned in articles by Dickinson’s revered friend, Samuel Bowles, as editor of the Springfield Republican.

In all of these arguments, white gets inevitably folded into attitudes towards race, a subject of particular contention at this moment of US history. In a more recent analysis from 2009, Wesley King agrees with earlier scholars that whiteness for Dickinson is “a contested site … almost always subjected to some form of reversal,” and that, putting aside Bennett’s argument,

Dickinson attempts to wrest some form of power from whiteness while in part avoiding the dominant ideological position such claims imply.

King takes another approach, using post-Freudian Lacanian theories of language and identity formation. Looking at two poems, one very early and one very late in Dickinson’s career, he teases out, quite remarkably, how Dickinson uses white imagery to explore the crisis

between the image and the word, or between the realm of appearances and language.

In doing so, King concludes, Dickinson works against the tide of her culture where white was becoming a sign of “natural authority,” to reveal

the linguistic and epistemological underpinning of racial hierarchy.

Many poets have written poems in the wake of this complicated history. Here are a few of our favorites: Robert Frost’s “Design,” Wallace Stevens’ “The Snow Man,” and Pat Parker’s “For the White Person who Wants to be my Friend.”

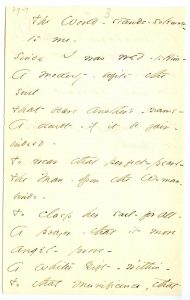

The World – stands – solemner– (F280A, J493)

The World – stands – solemner –

The World – stands – solemner –

to me –

Since I was wed – to Him –

A modesty – befits the

soul

That bears another’s – name –

A doubt – if it be fair –

indeed –

To wear that perfect – pearl –

The Man – opon the Woman –

binds –

To clasp her soul – for all –

A prayer, that it more

angel – prove –

A Whiter Gift – within –

To that munificence, that chose –

So unadorned – a Queen –

A Gratitude – that such

be true –

It had esteemed the

Dream –

Too beautiful – for Shape

to prove –

Or posture – to redeem!

Link to EDA manuscript: “Originally in Amherst Manuscript #set 89, p. 7. First published in Bolts of Melody, 1945. Courtesy of Amherst College.”

Most readings of this poem include it, along with “I’m ‘wife’– I’ve finished that–” (F225A, J199) and “A Wife – at Daybreak I shall be–” (F185A, J461) among a type of work Paul Crumbley calls the “bride poem,” and he identifies more than forty of them in Dickinson’s canon. These poems present Dickinson’s description and frequent critique of the popular cultural mythology of marriage, which saw it as essential to female self-completion. Crumbley notes that the majority of these poems

oppose expectation with actual experience, [and] reveal how the reality of marriage falls short of the dream engendered by society.

But he also observes that there are different kinds of brides in Dickinson’s work, including the “Brides of Christ” who enter into an often ecstatic spiritual union with divinity.

There are several allusions to whiteness in this poem, first in the “perfect–pearl” the man uses to bind the woman to him, and next in the prayer that the wife’s soul will prove “A Whiter gift–within”—that is, purer than the expense or excess of pearls, and for that she will be recognized as an “unadorned” “Queen.” We see a play of external appearance of richness set against an internal “munificence” of soul. But is it a “Dream – too beautiful” to hope for?

Sources

Crumbley, Paul. “Bride Poem.” An Emily Dickinson Encyclopedia. Ed. Jane Donahue Eberwein. Westport, CT.: Greenwood Press, 1998, 32-33.

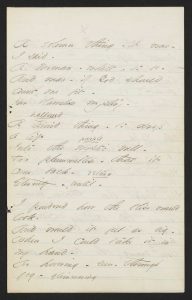

A solemn thing it was I said (F307A, J271)

A solemn thing – it was –

I said –

A Woman – white – to be –

And wear – if God should

count me fit –

Her blameless mystery –

A timid thing – to drop

a life

Into the +mystic well –

Too plummetless – that it

+ come back –

Eternity – until –

I pondered how the bliss would

look –

And would it feel as big –

When I could take it in

my hand –

As +hovering – seen – through

fog –

And then – the size of this

“small” life –

The Sages – call it small –

Swelled – like Horizons – in my

+breast –

And I sneered – softly – “small”!

+purple +return + glimmering +vest

EDA manuscript: “Originally in Packet XIV, ca. 1860-1862. First published in Poems, (1896). Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.”

This poem struck a discordant note for Dickinson’s first editor, Mabel Loomis Todd, who was always concerned with the salability of Dickinson’s works and the “protection” of her reputation. In Poems (1896), the third collection she co-edited with Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Todd gave the title “Wedded” to this poem, which Martha Nell Smith calls “culturally blasphemous,” and to make that title stick, Todd cut out the last two stanzas, where the speaker grew powerful and “sneered” at the “Sages” who dared see her life as “small.”

Many scholars see a direct allusion to Dickinson’s dressing in white in this poem. In an essay from 1983 titled “The Wayward Nun,” Sandra Gilbert says that though the poem is partly obscure, it is eminently clear that

Dickinson’s white dress is the emblem of a “blameless mystery,” a kind of miraculous transformation that rejoices and empowers her.

Maurya Simon calls this text

a poet’s poem: that is, one that focuses upon the poet’s relationship to her own power and that ultimately exposes her willingness to submit to that power.

Fog is an intriguing version of whiteness; not quite white, but blanking out the landscape or the mind. The conjunction of fog and “glimmering” as a variant for “hovering” sheds a glamor over this moment when the speaker holds the “bliss” of acceptance into the mysterious ranks and watches it swell into the limitlessness of horizons.

Sources

Gilbert, Sandra M. “The Wayward Nun beneath the Hill: Emily Dickinson and the Mysteries of Womanhood.” Feminist Critics Read Emily Dickinson. Ed. Suzanne Juhasz. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1983, 22-44, 40.

Simon, Maurya. “Poem 271.” Women’s Studies 16.1-2 (1989): 35-37.

Smith, Martha Nell. “‘To Fill a Gap.’” San Jose Studies 13.3 (Fall 1987): 3-25, 12-13.

Of Tribulation these are they (F328A, J 325)

Of Tribulation, these are They,

Denoted by the White –

The Spangled Gowns, a lesser Rank

Of Victors – designate –

All these – did Conquer –

But the ones who overcame

most times –

Wear nothing commoner than snow –

No Ornament, but Palms –

Surrender – is a sort unknown –

On this superior soil –

Defeat – an outgrown Anguish –

Remembered, as the Mile

Our panting Ancle barely passed –

When Night devoured the Road –

But we – stood whispering in

the House –

And all we said – was “Saved”!

EDA manuscript: “Originally in Poems: Packet XXIII, Fascicle 13, dated ca. 1861. First published by Higginson in the Atlantic Monthly (68 October 1891), 277. Courtesy of the Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.”

Dickinson included this poem in her July 1862 letter (L268) to Thomas Wentworth Higginson, where she called attention to the misspelling of “ancle” and, more importantly, where she explained that the “I” in her poems was “a supposed person.”

Emily Seelbinder argues that this poem, as others that refer to white clothes, borrows heavily from the Book of Revelation, chapter 7, a page that Dickinson dog-eared in her Bible. The chapter describes the celebrations of the children of Israel who have been “sealed the servants of our God” (Rev. 8:3-4), who form “a great multitude, which no man could number, of all nations, and kindreds, and people, and tongues … clothed in white robes” (Rev. 7:9). Here is the most relevant passage:

And one of the elders answered, saying unto me, What are these which are arrayed in white robes? and whence came they? And I said unto him, Sir, thou knowest. And he said to me, These are they which came out of great tribulation, and have washed their robes, and made them white in the blood of the Lamb.

Seelbinder goes on to notice the poem’s emphasis on “other-worldliness,” the inversion of worldly signs and spiritual signs, the transformation of earthly grief into heavenly triumph. We should note the interesting demotion of “Spangled Gowns” to a lesser Rank than the “white robes” of the righteous. Judith Farr discovered that in the 1860s, fashionable women like Dickinson’s worldly sister-in-law Susan showed a preference for “spangled” or sequined evening gowns. From this fact, Domhnall Mitchell concludes that white served Dickinson as

a determinant of virtue and value against vulgarity and excess.

Sources

Farr, Judith. The Passion of Emily Dickinson. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998, 41.

Mitchell, Domhnall. “Northern Lights: Class, Color, Culture and Emily Dickinson.” Emily Dickinson Journal 9.2 (2000) 74-83, 77.

Seelbinder, Emily. “The Bible.” Emily Dickinson in Context. Ed. Eliza Richards. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013: 69-77.

Dare you see a soul (F401A, J 365)

Dare you see a Soul

at the White Heat?

Then crouch within

the door –

Red – is the Fire’s common

tint –

But when the vivid Ore

Has vanquished Flame’s

conditions,

It quivers from the

Forge

Without a color, but the

light

Of unannointed Blaze.

Least Village, has it’s

Blacksmith

Whose Anvil’s even

ring

Stands symbol for the

finer Forge

That soundless tugs – within –

Refining these impatient

Ores

With Hammer, and

with Blaze

Until the Designated

Light

Repudiate the Forge –

EDA original manuscripts: Page 1, Page 2. “Part of the Amherst manuscripts. First published in the Atlantic Monthly by Thomas Higginson in 1891. Courtesy Amherst College, Amherst, MA.”

We discussed this poem in the post for January 8-14 on the Azarian School, where it exemplified the “distilled dramatic monologue” common to that then popular style. In this group of poems, we can focus more specifically on the references to white. In this poem, Dickinson uses her knowledge of white as encompassing all the colors of the spectrum in the speaker’s description of what happens when, in the process of forging metal, “the vivid Ore” defeats the “Fire’s common tint” of red, and quivers “Without a color, but the light/ of unannointed Blaze.” To be “anointed,” according to Dickinson’s Webster’s, means to be prepared or consecrated by oil, an action

of high antiquity. Kings, prophets and priests were set apart or consecrated to their offices by the use of oil. Hence the peculiar application of the term anointed, to Jesus Christ.

What this definition does not specify is who authorizes or does the anointing—in the case of prophets, kings, priests and Jesus, it is God. To be “unanointed” (notice that Dickinson spells it with two n’s) means to be unconsecrated or not authorized by God or a higher power. Thus, the most intense form of heat, white heat, and the white, rather than red, light of this forge are not authorized by a divine or outside force, but from within the soul or mind of the speaker, the “finer forge” of the second stanza.

But in the stunning final lines, the process of refinement or purification gets so intense that it produces a “Designated Light” that can repudiate (dismiss, renounce) altogether the forge, the physical shaping process, and perhaps symbols altogether. This specially distinguished light can be seen as a positive form of the “unanointed Blaze,” less ritualistic and more administrative, earthly, and the extremest form of purified, self-authorized white. It’s hard not to hear “or’s,” which means choices or contradictions or refusals to choose, in the word “Ores,” which are first “vivid” and then “impatient,” longing for purification.

Sources

Cody, Dan. “‘When one’s soul’s at a white heat’: Dickinson and the ‘Azarian School.’” The Emily Dickinson Journal. 1 (1 2010): 30-59. doi: 10.1353/edj.0.0217.

Vendler, Helen. Dickinson: Selected Poems and Commentaries. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University, 2010, 180-83.

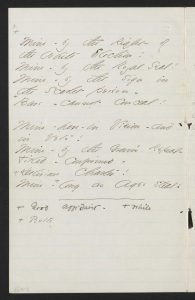

Mine by the right of the White Election! (F411A, J528)

Mine – by the Right of the White Election!

Mine – by the Royal Seal!

Mine – by the sign in

the Scarlet prison –

+Bars – cannot conceal!

Mine – here – in Vision – and

in Veto!

Mine – by the Grave’s Repeal –

Titled – Confirmed –

+Delirious Charter!

Mine – +long as Ages steal!

+Bolts + Good affidavit – +while

EDA manuscript: “Originally in Packet XIII, Mixed Fasciles, ca. 1862. First published in Poems (1890), 43. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.“

Readers give various and divergent contexts for this rousing, delirious declaration of possession. Perry Westbrook observes:

The choice of words echoes not only the speech of Emily’s lawyer father but also the old Puritan legalistic view of the Covenant of Grace whereby God enters into a contract with His elect.

This is the language of John Winthrop’s famous lay sermon, “Of Christian Charitie,” preached to the band of Puritans emigrating in 1630 to the northeast coast of North America, and Dickinson manages to show its continued relevance in a poem representative of Massachusetts Congregationalism.

Peggy Anderson relates the poem to a hymn, “Holy Bible, Book Divine,” which lends it a theological meaning. Elizabeth Philips thinks that Hawthorne’s well known novel The Scarlet Letter about Winthrop's Puritan settlement in Boson is a source for the poem and that the speaker is Dickinson’s version of Hester Prynne, a heroic figure of dissent against the puritanical founders of the Massachusetts Bay colony. Cynthia Wolff calls this a “heretical hymn,” arguing that a traditional one would celebrate the supremacy of God, whereas this poem

glorifies the individual’s ability to remain intact despite cosmic threats and bribes.

Wolff finds other poems that strike a similar tone,

though few others achieve the high pitch of hypnotic intensity.

Sharon Cameron reads “Mine by the Right of the White Election!” in the context of Fascicle 20, where Dickinson placed it, whose other poems are notable for their explicit sexuality. She argues that the whole fascicle, in a wonderful play on the title for Cameron’s own book (Choosing Not Choosing), is “choosing,” the advocacy of “a personal criterion–often a person’s criterion–for what is chosen and deemed acceptable, in opposition to a theological or social one.” Cameron argues that in this fascicle

the personal, the theological, and the social are first substituted, then equated, and then treated as interchangeable,

an “equivalence” demonstrated in this extraordinary poem.

Formally, this poem stands out for its use of anaphora, repetition of elements at the beginning of a line, a technique pioneered by and equated with the rebellious, often delirious, poetry of Dickinson's contemporary, Walt Whitman.

Sources

Anderson, Peggy. “The Bride of the White Election: A New Look at Biblical Influence on Emily Dickinson.” Nineteenth-Century Women Writers of the English-Speaking World. Ed. Rhoda B. Nathan. New York: Greenwood, Press, 1986.

Cameron, Sharon. Choosing Not Choosing: Dickinson’s Fascicles. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992.

Philips, Elizabeth. Emily Dickinson: Personae and Performance. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1988, 113-15.

Westbrook, Perry. Free Will and Determination in American Literature. Rutherford: Farleigh Dickinson University Press, 1979, 55-56.

Wolff, Cynthia. Emily Dickinson. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co., Inc. 1988, 198.

The Malay took the Pearl (F451A, J452)

The Malay – took the Pearl –

Not – I – the Earl –

I – feared the Sea – too

much

Unsanctified – to touch –

Praying that I might be

Worthy – the Destiny –

The Swarthy fellow swam –

And bore my Jewel – Home –

Home to the Hut! What lot

Had I – the Jewel – got –

Borne on a Dusky Breast –

I had not deemed a Vest

Of Amber – fit –

The Negro never knew

I – wooed it – too –

To gain, or be undone –

Alike to Him – One –

EDA manuscript: “Originally in Packet XXXIV, Fascicle 21, ca. 1862. First published in Bolts of Melody (1945), 131, from a transcript of A. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.”

Many scholars interpret this poem biographically, as an allegory of Dickinson’s rivalry with her brother Austin for the affections of Susan Gilbert, who eventually becomes his wife. It is one of several poems that describe Susan as Dickinson’s precious, luminously white “Pearl:” see “One life of so much consequence!” (F248), “Your riches taught me poverty” (F418), “Shells from the coast mistaking” (F716) and “Removed from accident and loss” (F417).

By contrast, Robert Weisbuch sees no biographical meaning in the poem, but a universal allegory about failure to take risks or to act, despite fears, on one’s passionate desires. In a reading from 1984, Vivian Pollak challenges this interpretation by insisting that the poem can be read outside of the Emily-Sue-Austin triangle but not outside of the “sexual temptations of Dickinson’s experiences.” In her essay from 2000, Pollak reads the poem along color and, specifically, racial lines, finding in it Dickinson’s “use of race as a politically subversive form of self-definition.” In this approach, Pollak sees an erotic competition in which the speaker, a white upper class woman, fears the sea (sexuality) and thus loses “the Pearl” to “an id figure” first described as a “Malay,” then as “The Swarthy fellow,” and finally as “The Negro” who evinces an “erotic self-confidence” the speaker lacks. Pollak concedes that this view has

its own kind of racism – the association of dark skin and sexual power being all too familiar,

but reads it rather as “figuring whiteness as a burden,” and so “opens up a space” to escape it.

Paula Bennett takes heated issue with some critics’ refusal to call out Dickinson’s racism, exemplified by Pollak’s reading. This racism, she argues, inheres in Dickinson’s invocation in poems and letters of conventional stereotypes, like the sexual prowess of dark-skinned men, assumptions she finds

pervading late nineteenth-century U.S. literature top to bottom, with minority writers themselves as likely as anyone else to invoke them.

Betsy Erkkila echoes this approach, suggesting that

religious symbolism joins with racial ideology and Western aestheticism to create a perdurable racist mentality–a psychology of whiteness.

Cristanne Miller takes a very different tack, finding the poem “as close as Dickinson comes to constructing an Orientalist tale,” based on the era’s fascination with pearl divers, stories and poems about which appeared at the time in Harper’s Monthly Magazine and the Hampshire and Franklin Gazette.

Sources

Bennett, Paula. “‘The Negro never knew:’ Emily Dickinson and Racial Typology in the Nineteenth Century.” Legacy 19.1 2001: 53-61.

Erkkila, Betsy. “Dickinson and the Art of Politics.” A Historical Guide to Emily Dickinson. Ed. Vivian Pollak. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004, 133-74, 52.

Farr, Judith. The Passion of Emily Dickinson. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 1992, 147-51.

Miller, Cristanne. Reading in Time: Emily Dickinson in the Nineteenth Century. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2012, 134-35.

Pollak, Vivian. “Dickinson and Poetics of Whiteness.” Emily Dickinson Journal 9.2 2000: 84-95.

Pollak, Vivian. Dickinson: The Anxiety of Gender. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1984, 155-56.

Weisbuch, Robert. Emily Dickinson’s Poetry. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1975, 57-58.

A transcript of the discussion of some of these poems that took place during the “Emily Dickinson Museum Poetry Discussion Group,” led by Ivy Schweitzer at Amherst College, January 18, 2019.

Sources

Bennett, Paula. “‘The Negro never knew:’ Emily Dickinson and Racial Typology in the Nineteenth Century.” Legacy 19.1 2001: 53-61.

King, Wesley. “The White Symbolic of Emily Dickinson.” Emily Dickinson Journal 18.1 2009: 44-68.

Mitchell, Domhnall. “Northern Lights: Class, Color, Culture and Emily Dickinson.” Emily Dickinson Journal 9.2 (2000) 74-83.

Vivian Pollak “Dickinson and Poetics of Whiteness.” in Emily Dickinson Journal 9.2 2000: 84-95.