On Choosing the Poems

Because Dickinson did not date or number her poems, we cannot determine the exact dates of their composition. Furthermore, we feel justified in taking some latitude about Dickinson’s writing on such an important subject as the Civil War. Thus, the poems for this week vary in date from late 1861 to early 1863. We also want to illustrate how fully Dickinson engages with the War, continuously grappling with the moral questions it posed in relation to other pervasive Dickinsonian themes – death, sacrifice, fear, faith, immortality. During this period, she never quite escapes the Civil War, because of the lasting effects it had on her family, community, ethics, politics, and world view.

Although the war was an ever-present backdrop, Dickinson wrote few poems directly about it, opting instead for natural metaphors, slanting imagery, or close comparisons and implications. Faith Barrett argues that

Although the war was an ever-present backdrop, Dickinson wrote few poems directly about it, opting instead for natural metaphors, slanting imagery, or close comparisons and implications. Faith Barrett argues that

Dickinson uses her Civil War poems to test out opposing ideological positions, sometimes skeptically questioning wartime ideologies and sometimes endorsing them. … Dickinson finds extraordinary imaginative freedom in poetry, with the possibilities it offers for equivocation, ambivalence, and reversal.

The poems selected below illustrate these qualities. We will return to this theme in later posts.

That after horror – that 'twas us – (F243, J286)

That after Horror – that 'twas us -

That passed the mouldering Pier -

Just as the Granite crumb let go -

Our Savior, by a Hair -

A second more, had dropped too deep

A second more, had dropped too deep

For Fisherman to plumb -

The very profile of the Thought

Puts Recollection numb –

The possibility – to pass

Without a moment's Bell -

Into Conjecture's presence

Is like a Face of Steel -

That suddenly looks into our's

With a metallic grin -

The Cordiality of Death -

Who +drills his Welcome in -

+nails

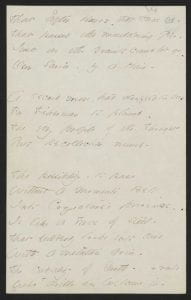

EDA manuscript: “Originally in Fascicle 11 (1861), and a letter to Higginson (1861). First published in Letters by Mabel Loomis Todd in 1894. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.”

This poem explores close encounters with death. Many scholars see it exploring death and the trauma such an experience brings, especially for soldiers who experience battle. The “Face of Steel” with its “metallic grin” suggests a “soldier looking into the barrel of a gun,” according to Dickinson biographer, Cynthia Wolff. This reading gains support when we learn that on hearing that her friend Thomas Higginson was seriously wounded during battle, Dickinson sent him a letter (L 282) containing the last eight lines of this poem.

Wolff’s reading also points out the Christian undertones in the poem, noting that Dickinson offers “nails” as a variation for the potent verb “drills” in line 15, which conjures up an image of the crucifixion, a frequent allusion in Dickinson’s poetry. Here, the “Face of Steel” is linked to the sinister face of “Our Savior” who, like a crumbling pier of granite, “let go” of us “by a Hair” and, thus, threw the world into horror.

Other scholars do not read an allusion to the Civil War in this imagery. Helen Vendler, for example, links it to a variety of anxieties surrounding death, universal to the human experience. Dickinson’s “terror” comes to mind, which she described in Letter 261 to Higginson as occurring in September of 1861.

Major motifs include the warlike imagery of machines, weaponry, and army “drills.” Also notable is the image of the “Face:” in stanza one, death is a “horror,” but in stanza two, it becomes a “profile of the Thought,” and by stanza three, it rears its fully revealed, personified “Face of Steel.” There is also a narrative in this poem: a quiet walk along an old pier that goes horribly wrong. Who is the “us” the speaker refers to? Wolff thinks it may be a pun on “U.S.,” adding to the Civil War connection.

Sources

Duchac, Joseph. The Poems of Emily Dickinson: An Annotated Guide to Commentary Published in English. 2 volumes, Hall, 1993. Note: these books are a compilation of other sources.

An Emily Dickinson Encyclopedia. Ed. Jane Donahue Eberwein. Westport, CT, 1998.

Letter 261. "Letters from Dickinson to Higginson" in the Dickinson Electronic Archive.

Vendler, Helen H. Dickinson: Selected Poems and Commentaries. Belknap Press, 2010, 84-85.

Wolff, Cynthia Griffin. Emily Dickinson. Perseus Books, 1999, 264-66.

The Doomed – regard the Sunrise (F298, J294)

The Doomed – regard the

Sunrise

With different Delight -

Because – when next it burns abroad

burns abroad

They doubt to witness it -

The Man – to die – tomorrow -

Harks for the Meadow Bird -

Because it's Music stirs

the Axe

That clamors for his head -

Joyful – to whom the

Sunrise

Precedes Enamored – Day -

Joyful – for whom the

Meadow Bird

Has ought but Elegy!

EDA manuscript: “Originally in Fascicle 12 (1862) in the 14th position. First published in The Atlantic Monthly in 1929. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.”

According to Cristanne Miller, the form of this poem, a 4 line stanza of 7686 syllables, was a favorite of Dickinson's and echoes the form of the poem, “The May Flower” by Edward C. Goodwin, which appeared in the Springfield Republican on May 16, 1857.

This poem centers around a sunrise, a symbol Dickinson uses frequently in her larger “mystic day” cycle as described in Barton Levi St. Armand’s Emily Dickinson and Her Culture: The Soul’s Society. The sunrise stands for birth and rebirth, resurrection, expectation, awakening, conviction, and, perhaps most importantly, hope. “The Doomed” could be soldiers in the war, a reading in which the soldiers’ new day brings bravery, relief, and hope back to life. Alternatively, “the Doomed” could be a criminal awaiting execution, and the poem could be a commentary on a contemporary debate on the death penalty in Massachusetts, mentioned in next week’s news. Dickinson personifies “the Axe,” a powerful image that removes some of the agency of war and violence from its human actors.

The first two stanzas stand in stark contrast with the last stanza, which describes how the “Joyful” regard the sunrise: with love, awe, beauty, and no worry about trouble. Here, Dickinson could be highlighting the separation between soldier and civilian. However, “Joyful” may also be an adjective, as in a joyful coming of the sun on a day long awaited by “the Doomed,” or a joyful sense of self-sacrifice in offering one’s life to a righteous cause, in the case of soldiers or religious martyrs.

Sources

Miller, Cristanne. Reading in Time: Emily Dickinson in the Nineteenth Century. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2012, 59.

St Armand, Barton Levi. Emily Dickinson and Her Culture: The Soul's Society. Cambridge University Press, 2009.

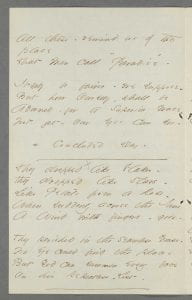

Unto like Story – Trouble has enticed me – (F300, J295)

Unto like Story – Trouble

has enticed me -

How Kinsmen fell -

Brothers and Sisters – who

preferred the Glory -

And their young will

Bent to the Scaffold, or in

Dungeons – chanted -

Till God's full time -* *whole – will -

When they let go the ignominy -

smiling -

And Shame* went still -* *Scorn *dumb.

Unto guessed Crests, my moaning

fancy, leads* me, *lures

Worn fair

By Heads rejected – in the lower

country -

Of honors there -

Such* spirit makes her perpetual *Some

mention,

That* I – grown bold - *till

Step martial – at my Crucifixion-

As Trumpets – rolled -

Feet, small as mine – have

marched in Revolution

Firm to the Drum -

Hands – not so stout – hoisted

them – in witness -

When Speech went numb -

Let me not shame their

sublime deportments -

Drilled bright -

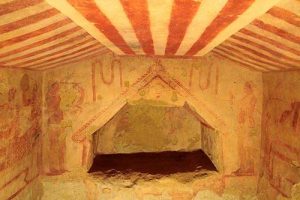

Beckoning – Etruscan invitation -

Toward* Light - *to -

EDA manuscript: “Originally in Fascicle 10 (1862). First published in Unpublished Poems edited by Martha Dickinson Bianchi and Alfred Leete Hampson in 1935. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.”

This poem can be read alongside “The Doomed – regard the Sunrise -” because both grapple with bravery and hope in relation to death and sacrifice. A kind of martyred heroism displays itself in this poem, as the speaker imagines herself going to war for her beliefs. Dickinson’s family had a copy of John Foxe’s The Book of Martyrs, originally published in 1563 and lavishly illustrated with woodcuts, that told stories of English Protestants martyred for their beliefs. Dickinson loved to read and reread this book.

This poem is a good example of Dickinson's experimentation with form. In a discussion of Dickinson's use of hymns, Cristanne Miller argues that is it more accurate to say

that she wrote in relation to song. Song, in this context, includes the hymns and ballads she sang, the poetry she read, and the popular music she played on the piano.

Miller asserts that although Dickinson “understood the integrity of the page … her poetry leans strongly toward what might be called a secondary or written orality.” This poem has an unusual stanza structure and unusual accentual syllabic pattern. Note the prevalence of four syllable lines and, in the last stanza, two syllable lines.

Paul Crumbley puts this poem among other “overtly political poems” that “combat the threat of complacency” by using an unreliable speaker “whose failures to activate the will serve as cautionary tales that dramatize faulty reasoning.” He argues that readers who “see through the speaker's rationalization” of small feet and not so stout hands “withhold their consent and independently imagine alternative courses of action.” This assertion of will allows readers to retain

sovereignty, in effect mimicking public acts of resistance and choice. This strategy invests the experience of reading with political significance even when the content of the poem is not overtly political. … Doing so draws readers into the creative process itself, democratizing the act of reading by leveling the authority of reader and text.

The phrase “Etruscan invitation” harks back to a rich and powerful civilization of ancient Italy, influenced by ancient Greek culture, that was eventually defeated, absorbed and defamed by the Roman Republic. Dickinson loved Italian culture. The phrase may refer to the Etruscan custom of lavishly decorated tombs, which “invite” martyrs to a “bright” afterlife.

It is notable that both this poem and “The doomed regard the sunrise” use the word “drills,” which in the previous poem has the variant “nails” and suggests the martyrdom of the Crucifixion.

Sources

Full text of The Book of Martyrs provided by Project Gutenberg.

Crumbley, Paul. “Democratic Politics.” Emily Dickinson in Context. Ed. Eliza Richards. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013, 179-187.

Miller, Cristanne. Reading in Time: Emily Dickinson in the Nineteenth Century. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2012, 49.

“Unto like Story – Trouble has enticed me -” The Prowling Bee. (photo)

They dropped like Flakes – (F545, J409)

They dropped like Flakes -

They dropped like stars -

Like Petals from a Rose -

When suddenly across the June

A Wind with fingers – goes -

They perished in the seamless Grass -

No eye could find the place -

But God can summon every face

On his Repealless – List.

EDA manuscript: “Originally in Fascicle 28 (1863). First published in Further Poems edited by Martha Dickinson Bianchi and Alfred Leete Hampson in 1929. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.”

This is one of the most famous Dickinson poems about the Civil War. Dickinson's first editors, Mabel Loomis Todd and Thomas Wentworth Higginson, recognized its subject and included it in the first collection of Dickinson's poems published in 1890 under the title “The Battle-Field.” To get a sense of the public conversation about the War, we can turn to the coverage of the Battle of Gettysburg, one of the bloodiest battles of the War, which took place on July 1-3, 1863. On July 8, 1863, Samuel Bowles, an important friend of Dickinson’s and editor of the Springfield Republican, wrote this about the battle:

Our soldiers credit the rebels with the most unyielding and fearless courage in the late battles. Torn to pieces as they are, having lost 30,000 or 40,000 men in this last five days, they are not used up. … Their endurance, their desperation, their utter disregard of life is surely worthy of a better cause.

Harper’s Weekly published an anonymous poem monumentalizing the victory, titled “Gettysburg.”

Dickinson’s poem participates in this conversation. It pits religious faith against the facts of nature through the dichotomy between an expected peaceful afterlife supposedly given by God and a strikingly sudden and unceremonious “drop” to death. The poem struggles with this issue in the second stanza especially, characterizing God as a ruthless reaper with a “Repealless – List.” The speaker questions which of the two powers, nature or God, is the truly merciful one, and the answer is up for debate.

Cristanne Miller points out that the poem's structure is the ballad measure's four line stanza with 8686 syllables and with the first line split metrically, a technique Dickinson uses in other poems. Miller also notes that

Dickinson comes closest to writing in a popular genre of the war in her nature poems that present war in relation to a natural or sacred order, some adopting traditional Christian attitudes and others imagining nature itself overwhelmed by the violence of war.

Shira Wolosky points out that the comparison between death and nature makes nature seem frightening, which is uncharacteristic for Dickinson; nature is usually an intoxicating, ecstatic force of beauty. Faith Barrett sees the poem presenting

war as an inevitable part of nature's cycle of death and rebirth, [and] thus seems to endorse wartime ideologies that argue that death in battle is a form of Christian martyrdom, a theological view widely held in both North and South.

Sources

Barrett, Faith. “Slavery and the Civil War.” Emily Dickinson in Context. Ed. Eliza Richards. NY: Cambridge University Press, 2013, 206-215.

Harper's Weekly, July 18, 1863, from Son of the South.

Miller, Cristanne. Reading in Time: Emily Dickinson in the Nineteenth Century. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2012, 159.

Springfield Republican, July 8, 1863.

Wolosky, Shira. Emily Dickinson: A Voice of War. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1984.

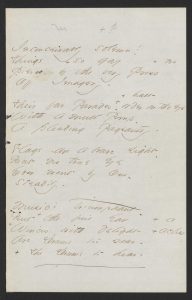

Inconceivably solemn! (F414, J582)

Inconceivably solemn!

Inconceivably solemn!

Things so gay

Pierce – by the very Press

Of Imagery -

Their far Parades – order* on the eye *halt

With a mute Pomp -

A pleading Pageantry -

Flags, are a brave sight -

But no true Eye

Ever went by One -

Steadily -

Music's triumphant -

But the* fine Ear *a

Winces* with delight *aches

Are Drums too near -* *The Drums to hear -

EDA manuscript: “Originally in Packet 10, and various fascicles. First published in The London Mercury in 1929. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.”

Even the small town of Amherst would have seen military parades of men going off to war during this time. Immediately, this poem fills the reader with a sense of foreboding and incongruity. Scholars note the jarring imagery: a parade should be a symbol of happiness, celebration, “things so gay.” But, instead, it frightens the watcher and evokes soldiers marching off to war. The music hurts the ears of the listener, almost like drums sounding like loud gunshots.

Ruth McNaughton calls the poem one of Dickinson’s explorations of the power of imagery, especially jarring, disturbing, or ironically set against its conventional character. Douglas Leonard suggests Dickinson’s striking imagery draws on “Burkean elements of the sublime,” and Pamela Matthews recognizes the disjunctive imagery as similar to the idea behind “Tell all the truth but tell it slant–.” What we imagine lying behind the parade is worse than any reality. Elizabeth Phillips notes Dickinson's poetic strategy, contrasting external events with their impact on the perceiver of them, with that of other poets of the Civil War, namely Herman Melville, who composed Battle-Pieces mostly from printed accounts, and Walt Whitman, who worked in a hospital tending the wounded and wrote from that intimate experience.

Stumped about a poem? Check out these “phone a friend” videos of Fiona Bowen, Dartmouth '18, and Sarah Miller, Dartmouth '19, discussing the poem.

Sources

Duchac, Joseph. The Poems of Emily Dickinson: An Annotated Guide to Commentary Published in English. 2 volumes, Hall, 1993. Note: these books are a compilation of other sources.

Leonard, Douglas. “‘Chastisement of Beauty’: A Mode of the Religious Sublime in Dickinson's Poetry.” University of Dayton Review 19.1 (1987): 39-47.

Matthews, Pamela R. “Talking of Hallowed Things: The Importance of Silence in Emily Dickinson's Poetry.” Dickinson Studies 47 (1983): 14–21.

McNaughton, Ruth F. The Imagery of Emily Dickinson. The University, 1949.

Phillips, Elizabeth. Emily Dickinson: Personae and Performance. Penn State Press, 1988.

Other Civil War poems not dated to circa 1862:

- It feels a shame to be Alive

- Success is counted sweetest

- And see the post for October 15-21 on Autumn, which discusses a cluster of poem about the battle of Antietam

Sources

Barrett, Faith. “Slavery and the Civil War.” Emily Dickinson in Context. Ed. Eliza Richards. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013, 206-15, 207.