On Choosing the Poems

As we explained in the post for this week, as Dickinson became more reclusive at this time in her life, she also began to think about possible fame and, thus, about possibly publishing her poems in print. She was already circulating them in letters to various friends and correspondents, which included several important and influential editors, who, she tells Higginson in her second letter to him later this month,

came to my Father’s House, this winter—and asked me for my Mind—and when I asked them “Why” they said I was penurious—and they would use it for the World — (L261)

Elliptical as usual, Dickinson suggests here that her poems are her “Mind,” and, thus, something to be guarded and only opened to intimates, and that print publication is “worldly,” perhaps, commodifying, although to “use” her poetry “for the World” can have any number of implications, positive and negative.

Still, Dickinson explored issues of publication, publicity, fame and “immortality” (her “flood subject” [L319]) in less spiritual and more literary terms. In 1863, she wrote the signal poem on this topic, “Publication – is the Auction / Of the Mind of Man,” which echoes the words she wrote to Higginson, and which we include in our cluster for this week. Another group of poems dated to 1865 meditate on issues of fame. In a poem dated 1877, she summed up:

To earn it by dis –

daining it

Is Fame’s consummate

Fee – (F1445A)

Because Dickinson continued to think and write about these issues, we include a list of related poems from beyond our focus year of 1862.

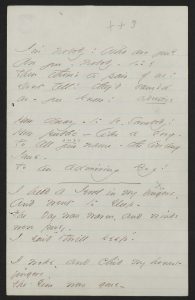

I'm Nobody! Who are you? (F260, J288)

I'm Nobody! Who are you?

Are you – Nobody – too?

Then there's a pair of us!

Dont tell! they'd banish us – you know!

advertise

How dreary – to be – Somebody!

How public – like a Frog -

one's

To tell your name – the livelong June –

To an admiring Bog!

EDA manuscript: "Packet VIII, Fascicle 11, ca. 1861. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. First published in Life, 17 (5 March 1891), 146, and Poems (1891), 21, with the alternatives not adopted and with the first two words of line 4 as the last of line 3.

Although this poem is dated to 1861, we include it in this cluster because of its popularity and because, though deceptively simple, it raises many salient questions about fame. Biographer Richard Sewall suggests that it is a “reduction” or distillation of a poem by Charles Mackay titled “Little Nobody” that found its way into the Springfield Republican in January 1858. Mackay’s poem, 24 lines in length, is a meditation on how the “storms of Fate” fall more painfully on the prominent. While it lacks the playful, even, arch tone of Dickinson’s poem, it highlights differences in status, which Dickinson’s poem seemingly ignores. Here are Mackay’s two refrains:

Blow, ye storms of Fate,

On the rich and great

I’m but little Nobody—Nobody am I.Kings may wake to weep,

While their plowmen sleep;

Who would be a Somebody? —Nobody am I.

In her poem, Dickinson adopts what scholars call her “child persona.” Cynthia Wolff, another biographer, sees this as strategic:

She uses this “Everyman figure of the child” to convince readers that they are in league with the speaker against the grown-up world,

a beguiling way to speak truth to power.

But why would a mature women (Dickinson was around 30 years old when she penned this poem) and, by this time, a prolific poet, feel or represent herself as a nobody? Scholars point to the gender conventions of 19th century New England in which women were, legally speaking,“femme couverte,” nobodies occluded under the protection of fathers or husbands. Many women writers resorted to personas, such as mythological figures, to disguise their voices and agency. In fact, Jane Eberwein argues that this poem echoes

Western mythology’s most memorable exploiter of submerged identity: Ulysses proclaiming himself No-man to evade Polyphemous.

Other readers point out how in rejecting reptilian “publicity,” like the print publication of poems, Dickinson creates an alternative space of significance and agency. The variant of “advertise” for “banish” in the 4th line is telling; both Franklin and Johnson chose it as closer to (what they understood to be) Dickinson’s meaning in the versions they print in their editions. “Banish,” however, is an important choice of diction in raising the stakes. As Susan Leiter points out,

banishment was traditionally a punishment for dissent against tyranny,

giving the poem a deeper political reading that some see as “democratic,” advancing support for the faceless masses.

The other diction choice scholars find important is “bog,” and it leads to an antithetical reading. Domnhall Mitchell sees this word as a denigrating allusion to the Irish immigrants who came over during this period and settled in towns like Amherst; several people employed in the Dickinson household were Irish. Its use here, he argues, expresses not sympathy for them, but

both anxiety and contempt for the democratic system that gives “bog-trotters” access to political and cultural influence.

Sources

Eberwein, Jane. Emily Dickinson: Strategies of Limitation. Amherst: University of Amherst Press, 1985, 61-2.

Leiter, Sharon. Critical Companion to Emily Dickinson: A Literary Reference to her Life and Work. New York: Facts on File, 2007, 111-12.

Mitchell, Domnhall. “Emily Dickinson and Class.” The Cambridge Companion to Emily Dickinson. Ed. Wendy Martin. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002:191-214, 197-99.

Sewall, Richard. The Life of Emily Dickinson. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1980, 673-74.

Wolff, Cynthia. Emily Dickinson. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co., Inc. 1988, 184.

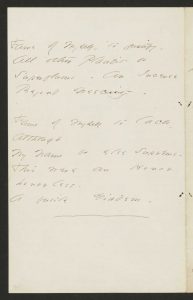

Fame of Myself, to justify (F481, J713)

Fame of Myself, to justify,

All other Plaudit be

Superfluous – An Incense

Beyond Nescessity –

Fame of Myself to lack -

Although

My Name be else supreme –

This were an Honor

honorless –

A futile Diadem –

EDA manuscript: "Originally in Poems: Packet XXXI, Fascicle 23, ca. 1862. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. First published in Bingham, Ancestors’ Brocades (1945), 171, from a transcript of A; also Bolts of Melody (1945), 237."

An explicit meditation on fame, this poem varies the familiar hymn measure of 8686 rhyming abcb to reveal subtle disruptions. In the first stanza, the 3rd line is only 7 syllables, which produces some irony because this line begins with the word “superfluous,” which means “excessive” but also “unnecessary,” a word that appears, superfluously, in line 4. While the rhymes scheme in this stanza is fairly exact—be/Necessity—it contrasts with the slant rhyme of the second stanza—supreme/diadem. These rhymes almost tell the story of the poem.

The structure of the poem is also a familiar Dickinson tactic, repeating the first line in the second stanza with a variation, often an antithesis: “Fame of Myself, to justify … Fame of Myself to lack.” The form asks us to compare these two possibilities, but what does the repeated line mean? Fame in and of the self, the self’s recognition of its own fame, fame that recognizes the self for what the self thinks it deserves? A self-empowering fame? Does this fame require public recognition or scorn it? The second stanza contains imagery of royalty and self-entitlement, especially the “diadem.” It may imply that to lack “fame” to/of oneself, even if one has public recognition (“My Name be else supreme”) is an “Honor honorless,” a “futile” form of entitlement.

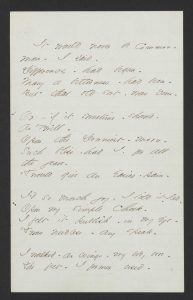

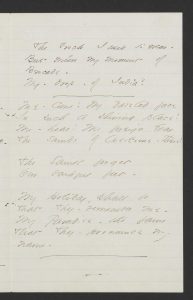

It would never be Common – (F388A, J430)

It would never be Common -

more – I said –

Difference – had begun –

Many a bitterness – had been –

But that old sort – was done –

Or – if it sometime – showed -

as 'twill –

Opon the Downiest – morn –

Such bliss – had I – for all

the years –

'Twould give an easier – pain –

I'd so much joy – I told it – Red –

Opon my simple Cheek –

I felt it publish – in my eye –

'Twas needless – any speak –

I walked – as wings – my body bore –

The feet – I former used –

Unnescessary – now to me –

As boots – would be – to Birds –

I put my pleasure all abroad –

I dealt a word of Gold

To every Creature – that I met –

And Dowered – all the World –

When – suddenly – my Riches shrank –

A Goblin – drank my Dew –

My Palaces – dropped tenantless –

Myself – was beggared – too –

I clutched at sounds –

I groped at shapes –

I touched the tops of Films –

I felt the Wilderness roll back

Along my Golden lines –

The Sackcloth – hangs opon the nail –

The Frock I used to wear –

But where my moment of

Brocade –

My – drop – of India?

EDA manuscript: "Originally in Poems: Packet XXVII, Fascicle 19. Includes 13 poems, written in ink, ca. 1862. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. First published in Unpublished Poems (1935), 98-99, as eight quatrains."

This is what critics call a poem of “aftermath,” poems that describe the consequences of some crisis that completely wrecks and alters the speaker’s world. But this poems spends a lot of time describing the before scenario, so that we get a full picture of what has been lost. What this crisis was, we do not know for sure. The description of it and the word “Goblin” connect it to the Gothic imagery of the Azarian School of writing, discussed in the second post in January, which often recounted crises that led to religious conversions:

When – suddenly – my Riches shrank –

A Goblin – drank my Dew –

My Palaces – dropped tenantless –

Myself – was beggared – too –

There are hints, however, that this is a poem in which, as Alice Fulton says, “a woman confronts literary effacement.” That is, the crisis is caused by a lack of publication and recognition. Fulton examines the poem’s “syntactical deletion, compression, and blurred pronouns.” Several words shimmer with this meaning, especially “publish” in the third stanza. The speaker is describing the time “before,” one of so much “bliss” and “joy” that “I told it – Red – Opon my simple Cheek,” in blushes, and “I felt it publish – in my eye–/ ‘Twas needless – any speak.” This publication comes from inside the speaker (“Fame of myself”?), and expresses itself through her eye/I; that is, publication is bodily, enlivening the whole self, and requires no speech or acknowledgement by others. In this elevated state, the speaker is fully expressive: “I put my pleasure all abroad–/ I dealt a word of Gold.” It is not hard to hear “God” in that last word, so that poetic activity is divine as well as enriching.

Then, the “Goblin” appears, sips all the dew, and rolls back paradise into a “Wilderness” that buries the speaker’s “Golden lines,” a direct allusion to poetry. There is an echo in these lines of Edgar Allan Poe's poem "Alone," in which a speaker describes his “difference” from others as the Heavenly blue of the sky obstructed by “a demon in my view.” Finally, the “drop – of India” evokes not only the exotic, sensual East but, more specifically, drops of “india ink” that probably indelibly marked the writer’s clothing with evidence of her work, marring her “moment of Brocade.” Jane Eberwein suggests that in this poem

Dickinson confronted the loss of dreams—deprivations of those imagined compensations that serve fanciful people as substitutes for the status, jewels, and property discovered to be elusive.

It is worth noting that the poem, “Me come! My dazzled face” (F389A, J431), written at the bottom of the second sheet in the fascicle in which this poem appears, is also about the speaker wishing for a spiritual type of “fame” being remembered only by “Saints,” which would constitute “My paradise.” On this theme, see also “I had the glory – that will do” (F350A, J349), also written in 1862.

Sources

Eberwein, Jane. Emily Dickinson: Strategies of Limitation. Amherst: University of Amherst Press, 1985, 63-64.

Fulton, Alice. “Her Moment of Brocade: The Reconstruction of Emily Dickinson.” Poetry in Review. 15. 1 (Spring 1989): 9-44, 27-43.

Wolff, Cynthia. Emily Dickinson. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co., Inc. 1988, 216-17.

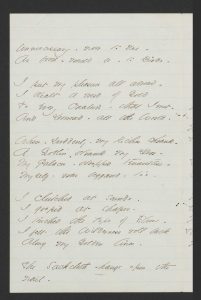

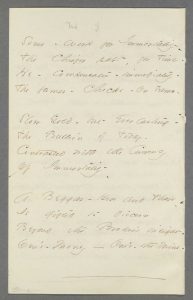

Some – Work for Immortality – (F536A, J406)

Some – Work for Immortality –

The Chiefer part, for Time –

He – Compensates – immediately –

The former – Checks – on Fame –

Slow Gold – but Everlasting –

The Bullion of Today –

Contrasted with the Currency

Of Immortality –

A Beggar – Here and There –

Is gifted to discern

Beyond the Broker's insight –

One's – Money – One's – the Mine –

EDA manuscript: "Originally in Poems: Packet XXV, Fascicle 28. Includes 23 poems, written in ink, dated ca. 1862. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. First published in Further Poems (1929), 5.

This poem artfully confuses the spiritual and literary meanings of “immortality,” which, in any case, becomes a kind of demanding employer. The whole enterprise is wreathed in implications of paid labor, compensation, currency “of Today” compared to the “Currency of Immortality.” This confusion expands the purview of the poem. Heather McHugh finds:

There is hardly a syntactical unit here which cannot be variously connected with the elements surrounding it,

a technique which creates

the greatest possible number of competing readings.

Cristanne Miller explores the imagery of payment, the “immortal fame” produced by “Slow Gold,” versus the “Money” of “immediate praise” and the pun on “Mine,” and concludes:

In 1863, [Dickinson] presciently and precisely distinguishes the advantage of writing in relation to her immediate world but not “for” any judge or gain from “Time”— or at least, her time.

Sources

McHugh, Heather. “Interpretive Insecurity and Poetic Truth: Dickinson’s Equivocation.” American Poetry Review. 17.2 (Mar.-Apr. 1988):49-54, 51-2.

Miller, Cristanne. Reading in Time: Emily Dickinson in the Nineteenth Century. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2012, 189.

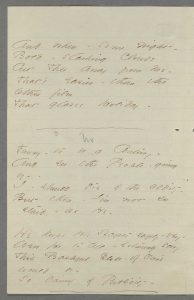

Funny – to be a Century – (F677, J345)

Funny – to be a Century –

And see the People – going

by –

I – should die of the oddity –

But then – I'm not so

staid – as He –

He keeps His Secrets safely – very –

Were He to tell – extremely sorry

This Bashful Globe of Our's

would be –

So dainty of Publicity –

EDA manuscript: "Originally in Poems: Packet XXXIII (mixed sets). Includes 26 poems, written in ink, dated ca. 1862-1864. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. First published Unpublished Poems (1935), 88, with the alternative not adopted."

Here, Dickinson considers fame and notoriety from the point of view of time, of a “Century.” This is the way recorded history reckons human activities and achievements, by hundred year groups. The reversal allows the poet to make revealing comparisons.

For example, she depicts the century as fixed while the people who live within time, within it, move past. The adjective Dickinson uses to describe the century is “staid,” which in her Dictionary means “Sober; grave; steady; composed; regular; not wild, volatile, flighty or fanciful.” Perhaps more importantly, the word derives from the verb “to stop.” By contrast, the speaker, who is “not so staid,” also thinks she “should die of the oddity” produced by such voyeurism, which perhaps gives us a glimpse into Dickinson’s horror of being exposed to public view. Who really is “staid” and who is “flighty, volatile, and fanciful”?

In the second stanza, the speaker describes “This Bashful Globe of Our’s” as “So dainty of Publicity,” which suggests a squeamishness the speaker earlier ascribed to herself. Publicity becomes a threat when there are “secrets” at stake, secrets better kept safely under wraps.

Sources

Hallen, Cynthia, ed. Emily Dickinson Lexicon. Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University, 2007.

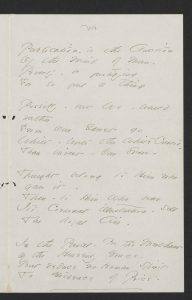

Publication – is the Auction (F788, J709)

Publication – is the Auction

Of the Mind of Man –

Poverty – be justifying

For so foul a thing

Possibly – but We – would

rather

From Our Garret go

White – unto the White Creator –

Than invest – Our Snow –

Thought belong to Him who

gave it –

Then – to Him Who bear

It's Corporeal illustration – sell

The Royal Air –

In the Parcel – Be the Merchant

Of the Heavenly Grace –

But reduce no Human Spirit

To Disgrace of Price –

EDA manuscript: "Originally in Poems: Packet XII, Fascicle 37. Includes 21 poems, written in ink, ca. 1863. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. First published in Letters (1894), 268, the first two lines; also Letters (1931), 245. Further Poems (1929), 4, entire, with the final two stanzas as one and the last word of line 11 as the first of line 12."

Dickinson never explored her position on publication more clearly than in this poem. It is dated to late 1863, but because it is so central to this theme, we include it in this group. It reflects a cultural shift apparent in the mid-19th century, in which writing morphed from an occupation of the leisured, wealthy class and educated gentlemen, into a paying profession that depended on publicity, reputation, and literary trends. It became a marketplace in which many women and friends of Dickinson, like Helen Hunt Jackson, found ways to support themselves and their families.

There are so many elements to notice that connect this poem to the others we have explored in this group. First we need to wrestle with the poem’s signal concept: publication as the “Auction / of the Mind of Man.” Several readers find in the word “auction” a reference to slave auctions and the reprehensible commodification of human life and spirit. While this is a resonance necessarily produced by the moment of the poem’s composition, it is somewhat unsettled by the references later in the poem to “white” as a signifier of innocence, purity, and divinity: “the White Creator.” Domnhall Mitchell argues that the word refers to the common practice of the time of auctioning off the household items of bankrupts, in order to pay off their debts. Being “dainty of publicity,” Dickinson would have found this public display humiliating in the extreme.

In either case, the poem associates publication with commercialism, with selling out and selling one’s soul, with corrupting the sacred expression of the spirit with crass materialism. For Helen Vendler, the formal qualities of the poem express this opposition:

The rhyming of “Heavenly Grace” with “Disgrace of Price” sets the antitheses of the poem in sharp relief.

While the tone here is uncompromising and, for some, high-handed in using a universalizing royal “we,” there are elements that jar. The image of the speaker dying unknown in a writer’s “Garret” is romantic in the extreme. In reality, Dickinson did not have to retreat to a garret and starve in the service of her art, though Mitchell argues that her family’s checkered financial and civic history (her grandfather was a financial over-reacher) motivates

the poem’s aesthetic and class-related distance from a potentially compromising encounter with the literary marketplace.

Sources

Mitchell, Domnhall. “Amherst.” Emily Dickinson in Context. Ed. Eliza Richards. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013, 13-24, 20.

Mitchell, Domnhall. “Emily Dickinson and Class.” The Cambridge Companion to Emily Dickinson. Ed Wendy Martin. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002:191-214,199.

Vendler, Helen. Dickinson: Selected Poems and Commentaries. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University, 2010: 333-35.

More Poems on Fame

Best things dwell out of sight (F1012A, J998) 1865

Ended ere it begun (F1048A, J1088) 1865

I was a phebe – nothing more (F1009A, J1009) 1865

Fame is a fickle food (F1702A) no date

Fame is the tint that scholars leave (F968A) 1865

The beggar at the door for fame (F1291A, J1240) 1873

To earn it by disdaining it (F1445A) 1877

Fame is the one that does not stay (F1507A, J1475) 1879