There is no color more connected to Dickinson than white. And since we named this project “White Heat,” we feel duty-bound to interrogate the implications of that word choice.

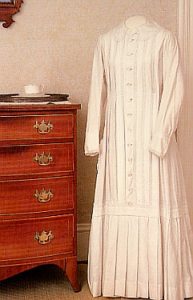

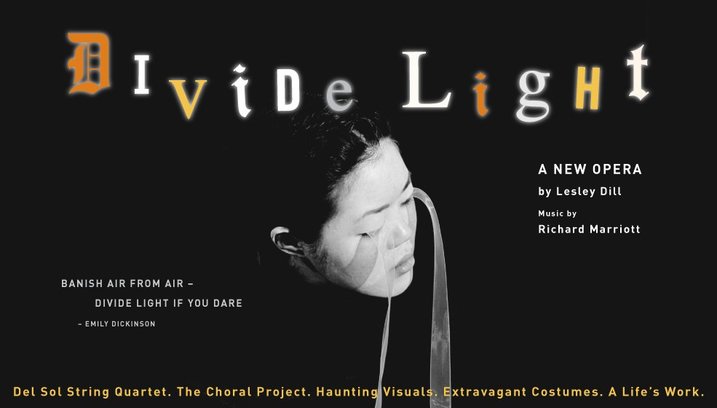

Seeing the project's title, a sympathetic colleague feared it invoked and, thus, endorsed the “myth” of Dickinson as the eccentric recluse in the white house dress she began wearing sometime around 1862, which is prominently on display at the Emily Dickinson Museum at the Homestead (though it is a replica! The original is at the Amherst Historical Society Museum). This humble garment, called a “wrapper,” with buttons down the front so she could dress herself and a discreet pocket for pencil and scrap paper, has been described as “the T-shirt and sweatpants of its day.” In the hands of contemporary artists, like Lesley Dill, this dress becomes a kinetic sculpture that highlights the power of Dickinson's words as well as racial identity.

Still, according to scholar Barton St. Levi Armand, the white dress quickly became a symbol for Dickinson’s public myth around town as “The White Moth of Amherst.” As soon as Mabel Loomis Todd, the young wife of a newly-appointed Professor at Amherst College, arrived in town in 1881, she heard about this “myth” or “moth” and proceeded to expand on and spread it. And it stuck.

What did this color choice stand for? Innocence or spiritual/sexual purity? Brides, bridal gowns and weddings? Coldness, snow, and the forbidding blankness of New England winters? Bones and marble, alabaster chambers, pearls, death shrouds and ghosts? Or renunciation of society—by 1869, Dickinson rebuffed an invitation to visit her “mentor,” Thomas Higginson, declaring,

I do not cross my father’s ground to any house or town. (L330).

In the now classic literary history, Madwoman in the Attic, Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar offer a series of possibilities for this fashion choice, including Dickinson as maid, nun, bird, corpse and ghost. Cheryl Walker reminds us that other women poets at the time wore white, including Maria Brooks, Christina Rossetti and Elizabeth Barrett Browning's heroine Aurora Leigh (of the long poem of that name), when she choose poetry as her life's work. As we detail in a later post, Dickinson adored Aurora Leigh.

As Dickinson's assumption of the white dress occurred during the years of the Civil War, we cannot ignore the meaning of white as a racial marker of class privilege and power, a category of identity that was undergoing cultural re-consolidation during this period. We have only to think of Herman Melville’s extensive meditation on “the whiteness of the whale” in Moby Dick (1851).

Dickinson is also a product of her time, class and region. It would be surprising if she did not harbor attitudes of race and class superiority, though there is profound disagreement among scholars about what her attitudes towards race and class privilege actually were, and whether they evolved over the course of her life.

What we can agree on is that Dickinson uses white and its related imagery throughout her poetry and letters. We chose the term “White Heat” as our project's title, from the poem,“Dare you see a soul at the ‘White Heat?’” (F401, J365) because it captured Dickinson’s intensity and the refining forge of creativity that characterized the year 1862 in her life. But that meaning does not cancel out the resonance of other meanings of white that appear in her work. With her extensive knowledge of astronomy, Dickinson would have known that white is not so much a color as a compendium of the full spectrum of colors.

“The Delicate Crow-quill of the Fair”

INTERNATIONAL

The Springfield Republican reported on rumors that Queen Victoria, who recently suffered the death of her beloved husband, Prince Albert, was a Swendenborgian, as was her late husband, and that

the consoling character of the convictions thence derived in regard to the nature of the transition that the world calls death

has helped to produce the “calmness and resignation” the Queen has shown in the face of this tragedy. Surprisingly, the writer does not condemn this revelation.

Reports on “the New Conquest of Mexico,” that Spain has taken advantage of the Civil War in the United States to “regain her old foothold on this continent,” and is joined by England and France. “Some of the Peruvian papers are urging union of the Spanish American states for mutual protection against European invasion.” But, the writer opines:

The true cause of the invasion is jealousy of the United States, and a desire to obtain a position on this continent so as to be in readiness to check our rising power if occasion should require.

NATIONAL

All the talk this week in the Springfield Republican is about the Burnside Expedition caught in storms and “delayed for a week or fortnight.” Readers would be eager to hear of the fate of this amphibious endeavor to close the blockade-running ports inside the Outer Banks of North Carolina, because Brigadier General Ambrose E. Burnside commanded troops primarily from New England.

The prospect of his being able to capture Newbern and to penetrate to Weldon or any other point where he can cut the railroad connection of Virginia with the South, has thus become sufficiently doubtful to give interest to adventure.

The upcoming battle of Newbern will have a large impact on the inhabitants of Dickinson’s Amherst, as we will see in an upcoming post.

“The Slavery Question.” In a long column, the writer considered: What should the government do with slaves who are seized and emancipated during the war? “The president’s suggestion of colonization abroad meets with little favor. Indeed everybody sees that the negroes are needed where they are, and that neither they nor the country will be benefited by their expatriation.” The writer finds evidence that emancipated slaves become useful citizens and, thus, argues that Congress should not do anything and let the war act as it will:

Already they have convinced some of our army officers, whose southern notions had made them skeptical on the subject, that the negro is capable of self-support and useful citizenship, as a free man, and that slavery is by no means essential to his industry or his well being in any respect.

In the Massachusetts legislature, there was some excitement about the governor’s veto of a bill extending state aid to families of the soldiers in General Butler’s New England division. “The great questions of finance connected with the support of the war—such as taxes, loans, treasury paper, etc.—are very actively discussed in the newspapers, but languidly acted on in Congress. We have reviving confidence, however, that the difficulties will be overcome, the credit of the United States preserved from any serious shock, and a good sound currency furnished to the loyal masses.”

“Piety and Patriotism:” The writer complains that “so little is heard from the chaplains in the volunteer army,” but adds, “Perhaps the most interesting letters from chaplains have been with respect to the negroes made free by the war.” The article then quotes a long passage by Chaplain Strickland from Beaufort, S.C. who narrates a “curious account of the celebration of Christmas eve by the freed negroes.”

They called the festival a “serenade to Jesus.” One of the leaders, of which there were three, was dressed in a red coat with brass buttons, wearing white gloves. The females wore turbans made of colored cotton handkerchiefs. All ages were represented, from the child of one year to the old man of ninety.

They sang hymns and spiritual songs,

and though none of them could read, it was remarkable with what correctness they gave the words. Their Scripture quotations were also correct, and appropriate … When asked as they could not read how they could quote the Scriptures, they replied: "We have ears, massa, and when de preacher give out his texts, den we remembers and says dem over and over till we never forgets dem. Dat’s de way, massa, we poor people learns de word of God."

Under “Dog Stories” appeared one entitled “Carlo,” but it was about a young terrier not Dickinson's beloved newfoundland.

Original Poetry: “A Portrait” by Caroline A. Howard of a young, “strangely fair” woman, alone, standing on the cliffs above the beach “as sculptured in the stone.” And “To Herbert. Je te n’oublirai jamais,” that captures the popular sentimental ethos of loyalty in love.

In "Books, Authors and Art:" A critical review of a novel by an unnamed male writer elicited this sarcastic comment, which illustrates the biases of the day and an awareness of them:

We were at first in some doubt as to the sex of this new genius, for it has been the gallant custom of critics to impute weak novels, characterized by copious verbal infelicities, to the delicate crow-quill of the fair.

“My Snow”

Although no letters are specifically dated to this week, during this period, Dickinson wrote several emotion-filled letters to Samuel Bowles, a family friend and editor of the Springfield Republican, who was ill and preparing for a trip to Europe. In one letter dated to early 1862 (L251), she begins,

Dear friend

If you doubted my Snow – for a moment – you will never – again– I know.Because I could not say it – I fixed it in the Verse – for you to read – when your thought wavers, for such a foot as mine –.

Dickinson then includes the poem, “Through the strait pass of suffering– / The Martyrs–even–trod,” which ends with an imagistic amplification of her reference to “Snow” in the extreme image of “polar Air:”

Their faith– the everlasting troth–

Their Expectation – fair–

The Needle – to the North Degree–

Wades – so– thro’ polar Air! (F 187A, J792)

The letters from this period also share some of the tenor and imagery of the Third “Master Document,” discussed in an earlier post; for example, a reference to “Chillon,” a castle on an island in Lake Geneva made famous by Lord Byron’s poem The Prisoner of Chillon (1816).

This poem tells the story of a monk, Francois Bonivard, the lone survivor of a martyred family who was imprisoned in the castle from 1532-1536. In addition to this image of martyrdom and imprisonment, Dickinson's “Master Document” contains a suggestive reference to white:

What would you do with me if I came ‘in white’? Have you the little chest to put the Alive–in? … I didn’t think to tell you, you didn’t come to me “in white,” nor ever told me why (L233).

Cynthia Wolff interprets these cryptic lines as references to writing poetry and in the context of the poem, “Mine–by the Right of the White Election!” which is one of the poems we discuss for this week.

One more important biographical context for the color white from later in Dickinson’s life. In a short poem sent to Susan Dickinson and dated 1871, Dickinson wrote:

White as an

Indian Pipe

Red as a

Cardinal Flower

Fabulous as a

Moon at Noon

Febuary [sic] Hour – (F1193A, J1250)

Dickinson reprises the image in a longer poem dated 1879, which is an apt example of her “it” poems—poems about an unidentified, often uncanny figure or experience. It is telling that Dickinson describes this “it” not only in terms of white things but as surpassing the whitest of them, as “whiter than the Indian Pipe:”

'Tis whiter than an Indian Pipe -

'Tis dimmer than a Lace -

No stature has it, like a Fog

When you approach the place -

Not any voice imply it here -

Or +intimate it there -

A spirit – how doth it accost -

+What function hath the Air?

This limitless Hyperbole

Each one of us shall be -

'Tis Drama – if Hypothesis

It be not Tragedy – (F1513A, J1482)+designate – +What customs -

The Indian pipe, or monotropa uniflora, also known as the ghost plant or corpse plant, is a small perennial plant native to the temperate regions of North America, Asia, and South America.

It gets its name from its coloration—or lack thereof—which is pure white, with sometimes a pink or red tinge and a yellowish flower flecked with black. It is white because it contains no chlorophyll. Rather than deriving energy from the sun, it is parasitic on certain trees, especially beech, and can grow in the dark understory of forests. It appears in early summer to early fall and often after a rain.

In early September 1882, Mabel Todd sent Dickinson her painting of Indian pipes, and Dickinson wrote back thanking her for “the preferred flower of life” (notice, she does not say, “my” preferred flower of life!), and enclosing a poem (“A Route of Evanescence” [F1489, J1463]) with the message, “I cannot make an Indian Pipe but please accept a Humming Bird.”

When Todd co-edited the first posthumously published volume of Dickinson’s poems in 1890, her rendering of the Indian pipes appeared on the cover.

When Todd co-edited the first posthumously published volume of Dickinson’s poems in 1890, her rendering of the Indian pipes appeared on the cover.

Reflection

Michael Amico

White contains all the colors of the spectrum … That makes me think that white collapses all points on a cultural map or a social topography. It does not negate them into an abyss of blackness. The points are still there, but their exact size, shape, and whereabouts seem not to matter. White is the mark of no-one-thing and no-one-where.

White contains all the colors of the spectrum … That makes me think that white collapses all points on a cultural map or a social topography. It does not negate them into an abyss of blackness. The points are still there, but their exact size, shape, and whereabouts seem not to matter. White is the mark of no-one-thing and no-one-where.

This blog uses news of the Dickinson family, the town of Amherst, the country and the globe, to cast light on Dickinson’s poems and give their particular words and phrases some color. Meanwhile, in the field of race studies, scholars are increasingly elucidating how the concept of a “white race” has asserted a kind of omnipotence and omniscience (containing “all”) when, in reality, it has been shading and apportioning all sorts of colors to itself and others with deadly consequence. As this week’s blog post tells us, scholars have also been asking what “whiteness” might signify for Dickinson as a “white person” in a racially “white” world.

I am not a scholar of Dickinson and hardly a regular reader of her work, until I began following this blog. What has struck me most is that Dickinson, let alone her poems, absorbs all the many historical and biographical and literary points we pin on and around her and her poems. She and they give no answer back, yield no colors other than the ones we shade and apportion to her and her work. That process of absorption without yielding is, for me, the whiteness of her and her poems.

The poems do not alone or together stage an argument about anything or anyone because the values that course through them are not stably ranked or even clear. The thinking and feeling that happens there is cut and re-cut so continuously across words and their letters, individual sounds, marks on the page, that I never know “what,” if anything, is important and why. Dickinson writes at the edge of any signifying chain. Wesley King analyzes the poems in this vein, as the editors here quote him,

to explore the crisis “between the image and the word, or between the realm of appearances and language,” and reveal “the linguistic and epistemological underpinning of racial hierarchy.”

Surely the poetry does that, but not in the service of that goal. Rather, the writing seems to set as its task the claim, or maybe it needs to be the creation, of a position that is not a position, more powerful than any hierarchy, even if it were on top, which it has no interest in being.

Can you write that white? Perhaps the strength involved in containing all colors, and not leaning on a particular combination of colors to develop a categorizable “voice,” is simply too much for most people to harbor. Perhaps the more routine life of the women around Dickinson in Amherst, women who were out and about in colorful array, would have mitigated against the focus and effort, the very power of thought, needed to write as white as she did.

Dickinson’s way does not at all court madness, the dissolution of self, for that is the abyss of blackness, the absence of all color.

If you thought and wrote like Dickinson, you would get bored of socializing. You would see how the “content” of anyone’s mind, including your own, was an illusion, and your pen would cut right through it to … the paper. And there you would act out the social masquerade in a play of words and sounds and marks. We would look for you and others there, try to identify feelings and thoughts and events, and you would be … What? Where?

On to the next poem.

bio: Michael Amico holds a PhD in American Studies from Yale University. His dissertation, “The Forgotten Union of the Two Henrys: The True Story of the Peculiar and Rarest Intimacy of the American Civil War,” is about the romance between Henry Clay Trumbull and Henry Ward Camp of the Tenth Connecticut Regiment. He is the author, with Michael Bronski and Ann Pellegrini, of “You Can Tell Just by Looking”: And 20 Other Myths about LGBT Life and People (Beacon, 2013), a finalist for the Lambda Literary Award in Nonfiction. He is presently a Researcher at the Center for the History of Emotions at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development in Berlin and can be reached at mjamico@gmail.com.

Sources

Overview

Dill, Lesley, artist.

Sewall, Richard. The Life of Emily Dickinson. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1980, 173.

St. Armand, Barton Levi. Emily Dickinson and Her Culture: The Soul’s Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984.

Walker, Cheryl. “A Feminist Critic Responds to Recurring Student Questions about Dickinson.” Approaches to Teaching Dickinson's Poetry. Edited by Robin Riley Fast and Christine Mack Gordon. New York: MLA, 1989, 142-47, 143.

History

Springfield Republican Feb 1, 1862

Biography

Wolff, Cynthia. Emily Dickinson. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co., Inc. 1988, 409.