On Choosing the Poems and Letter

By the time Dickinson wrote her third letter to Higginson, seven weeks after her initial contact with him, she was, according to biographer Alfred Habegger, settled in her opinion of him:

Convinced by Higginson’s initial critique that he was prepared to take her seriously, Dickinson responded with a series of unparalleled self-disclosures.

In order to see these self-disclosures and weigh them against “the poet’s fondness for self-dramatization,” we invite you to explore the June 7th letter in detail, not only as a context for the poems but as an aesthetic text in its own right.

In our post on Dickinson’s first letter to Higginson, we quoted the work of several scholars who treat the letters as literary texts and important intertexts for the poems. Thomas H. Johnson makes this case in his “Introduction” to The Letters of Emily Dickinson:

Indeed, early in the 1860’s, when Emily Dickinson seems to have first gained assurance of her destiny as a poet, the letters both in style and rhythm begin to take on qualities that are so nearly the quality of her poems as on occasion to leave the reader in doubt where the letter leaves off and the poem begins.

Other scholars, like Agnieszka Salska and Cindy MacKenzie, see the letters as staging grounds for the poetry and the poems as “inflected by the properties of epistolarity.”

We also include several poems related to the letter by theme and imagery, in order to round out our exploration of Dickinson’s relationship to Higginson and her search for a literary friend and respondent.

Sources

Johnson, Thomas. “Introduction.” The Letters of Emily Dickinson. Eds. Thomas Johnson and Theodora Ward. 3 vols. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1958, xv-xxii, xv.

MacKenzie, Cindy.“‘This is my letter to the World:’ Emily Dickinson’s Epistolary Poetics.” Reading Emily Dickinson’s Letters: Critical Essays. Eds. Jane Donahue Eberwein and Cindy MacKenzie. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2009, 11-27.

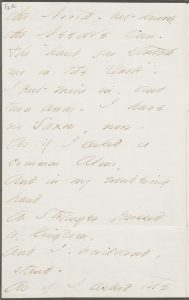

Dickinson to Higginson, June 7, 1862 (Letter 265)

7 June 1862

Dear friend.

Your letter gave no Drunkenness, because I tasted Rum before – Domingo comes but once – yet I have had few pleasures so deep as your opinion, and if I tried to thank you, my tears would block my tongue -

My dying Tutor told me that he would like to live till I had been a poet, but Death was much of Mob as I could master – then – And when far afterward – a sudden light on Orchards, or a new fashion in the wind troubled my attention – I felt a palsy, here – the Verses just relieve -

Your second letter surprised me, and for a moment, swung – I had not supposed it. Your first – gave no dishonor, because the True – are not ashamed – I thanked you for your justice – but could not drop the Bells whose jingling cooled my Tramp – Perhaps the Balm, seemed better, because you bled me, first.

I smile when you suggest that I delay "to publish"- that being foreign to my thought, as Firmament to Fin – If fame belonged to me, I could not escape her – if she did not, the longest day would pass me on the chase – and the approbation of my Dog, would forsake me – then – My Barefoot – Rank is better -

You think my gait “spasmodic” – I am in danger – Sir -

You think me “uncontrolled” – I have no Tribunal.

Would you have time to be the “friend” you should think I need? I have a little shape – it would not crowd your Desk – nor make much Racket as the Mouse, that dents your Galleries -

If I might bring you what I do – not so frequent to trouble you – and ask you if I told it clear – ’twould be control, to me -

The Sailor cannot see the North – but knows the Needle can -

The “hand you stretch me in the Dark,” I put mine in, and turn away – I have no Saxon, now -

As if I asked a common Alms,

And in my wondering hand

A Stranger pressed a Kingdom,

And I, bewildered, stand-

As if I asked the Orient

Had it for me a Morn-

And it should lift it’s purple Dikes,

And shatter me with Dawn!

But, will you be my Preceptor, Mr Higginson?

Your friend

E Dickinson -

EDA manuscript: Originally in MANUSCRIPT: BPL (Higg 52). Ink. Envelope addressed: T. W. Higginson./Worcester./Mass. Postmarked: Amherst Ms Jun 7 1862. Courtesy of Boston Public Library, Boston, MA. First published in Atlantic Monthly LXVIII (Oct. 1891) 447; Letters (1894) 303-304.

Thomas Johnson’s only note on this letter is the following:

The phrase “I have no Saxon” means “Language fails me”: see Poems (1955) 197, where in poem no. 276 she offers “English language” as her alternative for “Saxon.” She enclosed no poems in this letter.

The poem Johnson refers to is “Many a phrase has the English language” (F333A, J276), which we discuss below. This is an example of how the themes and imagery in the letters and poems interact.

We can take our cue from this, and following the flow of Dickinson’s clusters of images, compare her poetic elaboration of similar imagery. Thus, the first paragraph, in which Dickinson thanks Higginson for his “opinion” on the poems she enclosed in the previous letter, uses imagery of intoxication, rum, and “Domingo,” a reference to St. Domingo, the capital city of the Dominican Republic, which produced the sugar needed to make rum. Dickinson elaborates on images related to intoxication in “We–bee and I –live by the quaffing” (F244 B, J230), discussed below, and “I taste a liquor never brewed” (F207B, J214).

The next paragraph sets up Dickinson’s final request to Higginson in this letter by referring to her earliest “tutor,” Benjamin Newton, his premature death and her own association of poetry as a relief from illness, a topic explored in last week’s post. The third paragraph refers directly to Higginson’s criticism of her poetry as a form of “bloodletting,” a common medical treatment for several ailments that was still in practice at the time, and his praise and sincere attention as a form of “Balm,” which the Dickinson Lexicon defines as a “remedy; soothing cream; pain-relieving ointment.” We might think about this cluster in terms of the poem “Kill your balm and it's odors bless you”(F309A, J238).

The fourth paragraph contains Dickinson’s famous rejection of publication and fame and embrace of her “Barefoot-Rank.” A fascinating intertext for this subject is the 1860 poem “I met a king this afternoon!” (F183A, J166), a parable about meeting a “King” whose uncrowned, ragged but clearly “royal” condition Dickinson calls “this Barefoot Estate.” Her disavowal of print publication and fame can be read in terms of the following stinging one-liners, in which Dickinson rejects Higginson’s characterization of her poetic meter as “spasmodic,” a word associated with the Azarian School of writers which Higginson earlier applauded, and herself as “uncontrolled,” which then sets up her final request: “Would you have time to be the ‘friend’ you should think I need?”— her “Preceptor.”

In keeping with her emphasis on the physicality of relations, Dickinson represents Higginson’s letter as a “hand” stretched out to her “in the Dark,” a form of rescue, and she takes it, though very much in a spirit of friendship and equality that belies her diminished self-representations.

Sources

Hallen, Cynthia, ed. Emily Dickinson Lexicon. Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University, 2007.

Dickinson, Emily. The Letters of Emily Dickinson. Eds. Thomas Johnson and Theodora Ward. 3 vols. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1958, xv-xxii, 409.

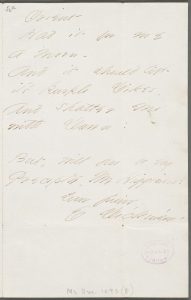

As if I asked a common Alms (F14B, J323)

As if I asked a

common Alms,

And in my wondering

hand

A Stranger pressed

a Kingdom,

And I, bewildered,

stand –

As if I asked the Orient

Had it for me

a Morn –

And it should lift

it's purple Dikes,

And shatter Me

with Dawn!

EDA manuscript: Originally in BPL – Ms. Am. 1093(8) – p. 6. Courtesy of Boston Public Library, Rare Books and Manuscripts Collection, Boston, MA. First published in Higginson, Atlantic Monthly, 68 (October 1891), 447, and Letters (1894), 304, in the letter to him (B).

This is the poem Dickinson included in the body of her third letter to Higginson, when words fail her as she attempts to thank him for what she calls in this letter his “friendship.” Dickinson copied this poem as the 13th in the very first Fascicle she put together in 1858. Elizabeth Hewitt finds that this Fascicle is governed by economic and financial tropes, which are not, as some readers think, “facetious” or critical, but indicate Dickinson’s belief

that social and erotic relations like monetary or commercial ones, operate similarly: value is not intrinsic, but determined by exchange … the greater the risk of loss, the more potential value should accrue to the investor.

Perhaps this logic of “speculative capitalism” appears more clearly in the fascicle context. In the epistolary context of the third letter to Higginson, it reads more like the wonderment of a needy person with rather modest desires and requests, who is surprised by the inestimable treasures she unexpectedly receives. The speaker asks for “a common Alms,” the last word signifying

Donation; contribution; free will offering, financial aid for the needy, gratuitous gift for the poor; (see Acts 3.2-3); [fig.] kindness; favor; blessing; service

according to the Dickinson Lexicon. Instead, she gets a “Kingdom,” which renders her royal—and masculine (though kingdoms held queens)? And asking the east for “a Morn,” the speaker is shattered by a spectacular sunrise. These are quite revelatory terms in which to express her gratitude for Higginson’s presence in her life.

Sources

Hallen, Cynthia, ed. Emily Dickinson Lexicon. Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University, 2007.

Hewitt, Elizabeth. “Economics.” Emily Dickinson in Context. Ed. Eliza Richards. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013: 188-97, 191.

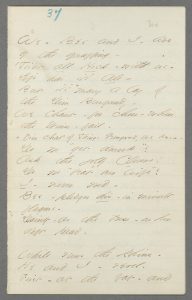

We–bee and I–live by the quaffing (F244 B, J230)

We – Bee and I – live

by the quaffing –

'Tis'nt all Hock – with us –

Life has it's Ale –

But it's many a lay of

the Dim Burgundy –

We chant – for cheer – when

the Wines – fail –

Do we "get drunk"?

Ask the jolly Clovers!

Do we "beat" our "Wife"?

I – never wed –

Bee – pledges his – in minute

flagons –

Dainty – as the tress – on her

deft Head –

While runs the Rhine –

He and I – revel –

First – at the Vat – and latest at the Vine –

Noon – our last Cup –

"Found dead" – "of Nectar" –

By a humming Coroner –

In a By-Thyme!

EDA manuscript: Originally in Poems: Packet XXXVII, fascicle 10, Houghton Library – (200a). Includes 22 poems, written in ink, ca. 1860-1861. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. First published in Atlantic Monthly, 143 (February 1929), 181, and Further Poems (1929), 61, in twenty-two lines without stanza division, from the fascicle (B). The alternative was not adopted.

In what might be a male persona poem, the speaker portrays himself as the drinking buddy of a bee, who survives by “quaffing,” a word that already implies, according to Dickinson’s Lexicon, excess: “inebriation; intoxication; act of imbibing; hearty consumption of liquor.” Its figurative meanings are “experience; pleasure; delight; enjoyment of life.” This speaker is a close companion of the tippler of “I taste a liquor never brewed”(F207, J214), who describes themself as:

Inebriate of air am I,

And debauchee of dew.

So that when Dickinson assures Higginson that his letter did not lead her into inappropriate intoxication, we have to hear the metaphorical realm of pleasure and sheer physical euphoria in nature this imagery implies.

This poem, however, takes the metaphor quite far, and might reflect, humorously, some of the temperance rhetoric afoot in Amherst and Springfield we saw in the section of the post on “This Week in History.” “Getting drunk” and “beating our Wife” are extreme intemperate behaviors that the speaker sidesteps by countering, “I – never wed.” But they were real-life dangers women faced from drunken husbands, which led them to create a Temperance Movement that was later taken over by men.

This poem mocks that movement and/or appropriates the language of intemperance for a female poet, who loved to make and imbibe currant wine. As long as the “Rhine,” the “Chief river in Germany” but also a figure for “wine; sweet drink from grapes” as well as “spirit; breath of life” according to the Lexicon, runs freely in the garden, the bee and speaker “revel” and by “Noon” are “’Found dead–‘of Nectar’” by the hummingbird/coroner in a patch of thyme. They die by excessively indulging in the essence of flowers and life, not a bad death, all things considered.

Sources

Alexander, Ruth M. “Class and Domesticity in the Washingtonian Temperance Movement,1840-1850.” The Journal of American History vol. 75, no. 3: 1988, 763-785.

Hallen, Cynthia, ed. Emily Dickinson Lexicon. Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University, 2007.

Koukoutsis, Helen. “‘We – Bee and I – Live by the Quaffing –’: Seduction and Volitional Freedom in Emily Dickinson’s Alcohol Poems.” The Emily Dickinson Journal, vol. 27, no. 1: 2018, 74–93, doi:10.1353/edj.2018.0004.

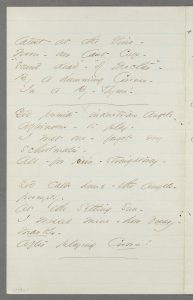

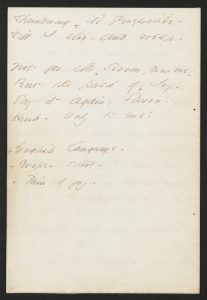

Bound – a trouble (F240A, J269)

Bound a Trouble – and

Lives will bear it –

Circumscription – enables Wo –

Still to anticipate – Were

no limit –

Who +were sufficient to Misery?

State it the Ages – to a

cipher –

And it will ache con –

tented on –

Sing, at it's pain, as any

Workman –

Notching the fall of the

even Sun -

+ could begin on

EDA manuscript: Originally in Poems: Packet XV, Fascicle 9, Houghton Library – (78c, d). Includes 29 poems, written in ink, ca. 1862. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. First published in Bolts of Melody (1945), 95, from a transcript of A (a tr168).

This poem is written in stanzas of long lines, often 9 syllables; Dickinson copied it into Fascicle 9. We include it as an elaboration of Dickinson’s reference in her letter to Higginson to being “bled” by the “surgery” of his critique of her poems. The first stanza parallels the “measured” and “limited” bleeding of a body for medicinal purposes with an “algebra” of pain inflicted on the soul. If a trouble can be bound, or limited, we can bear it. It’s the unknown extent of pain that is unbearable.

The second stanza is about “telling” or expressing the pain, which is also a form of binding or limiting it. “Cypher” is a resonant word for Dickinson. Her Lexicon notes its meaning as:

Zero; nonentity; numeral which has no value by itself, but which increases or decreases the value of other figures according to its position,

Even telling one’s pain to a nobody makes it bearable, just as “any Workman” counts off the hours until the end of the workday. And yet, this paraphrase does not quite capture the eerie sense of doom and resignation that hangs over these lines.

Sources

Hallen, Cynthia, ed. Emily Dickinson Lexicon. Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University, 2007.

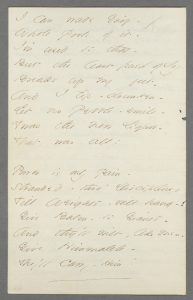

I can wade grief (F312A, J252)

I can wade Grief –

Whole Pools of it –

I'm used to that –

But the least push of Joy

Breaks up my feet –

And I tip – drunken –

Let no Pebble – smile –

'Twas the New Liquor –

That was all!

Power is only Pain –

Stranded – thro' Discipline,

Till Weights – will hang –

Give Balm – to Giants –

And they'll wilt, like Men –

Give Himmaleh –

They'll carry – Him!

EDA manuscript: Originally in Packet XXIII, Fascicle 13 (part), Houghton Library – (126b). Includes 11 poems, written in ink, dated ca. 1861. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. First published in Poems (1891), 30.

Dickinson copied this poem into Fascicle 13, in the second place, in early 1862. Two of its key images reprise or, perhaps more accurately, echo (since the poem was probably written earlier than June 1862) images in her third letter to Higginson: drunkenness and balm. Yet, the feeling here is very different from the carefree tippler in “We–bee and I –live by the quaffing,” and lends a darker cast to these references in the letter.

This speaker is overcome by “the least push of Joy,” because her accustomed state is one of grief, “whole pools” that she has to wade through. The intoxication occasioned by even a glimpse of joy is framed by grief, which teaches, or disciplines, the speaker. It is like practicing with weights, which act like ballast but also measure how much we can bear. According to Dickinson’s Lexicon, “stranded” does not have our modern sense of “abandoned” but rather means “To drive or force aground,” that is, to stabilize and immobilize. In this crucial formulation, Dickinson defines “power” as the ability to master or bear pain through internal self-regulation. She illustrates this insight by the example of giants, who, given “Balm” or comfort, fall apart. But give them a mountain range like the mighty Himalayas, and they become Atlas, able to bear the weight of the world.

Sources

Leiter, Sharon. Critical Companion to Emily Dickinson: A Literary Reference to her Life and Work. New York: Facts on File, 2007, 92-93.

Vendler, Helen. Dickinson: Selected Poems and Commentaries. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University, 2010, 115-17.

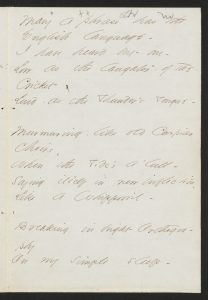

Many a phrase has the English language (F333A, J276)

Many a phrase has the

English language –

I have heard but one –

Low as the laughter of the

Cricket,

Loud, as the Thunder's Tongue –

Murmuring, like old Caspian

Choirs,

When the Tide's a'lull –

Saying itself in new inflection –

Like a Whippowil –

Breaking in bright Orthogra –

phy

On my simple sleep –

Thundering it's Prospective –

Till I +stir, and weep –

Not for the Sorrow, done me –

But the +push of Joy –

Say it again, Saxon!

Hush – Only to me!

+ Grope– • start– +Pain of joy–

EDA manuscript: Originally in Packet XIV, Mixed Fasciles, ca. 1860-1862. First published in Unpublished Poems (1935), 89, with the alternatives not adopted. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.

Dickinson copied this as the twenty-fourth poem in Fascicle 12 in early 1862. We discussed it in an earlier post but include it here as a poem Johnson explicitly connects to Dickinson’s third letter to Higginson. It also continues themes of grief and joy explored in the previous poem, “I can wade grief.”

As we said earlier, this is a poem about the power of spoken language. What is the phrase, spoken only to the speaker, that has the power to “break” into their sleep, stir them, make them grope, start and weep? The first part of the poem compares the mysterious phrase to many natural sounds, soft and thunderous. But what the speaker begs for at the end, is to hear the phrase in a human language, the voice of another person. “Saxon,” as Johnson says, refers to the “Germanic tribe that conquered the Celts in Britain” and stands for the English language, a conqueror’s tongue. There is something delicious in the secret whispered only to the speaker, but the feeling is characteristically ambivalent: the speaker is moved, haunted, awakened and weeps not for sorrow but “for the push” and/or “the pain of joy.” Perhaps because to speak and hear is to be in physical proximity, the intense face-to-face relation that Dickinson often longs for.

Sources

Hallen, Cynthia, ed. Emily Dickinson Lexicon. Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University, 2007.