On Choosing the Poems

In his 1891 essay, “The Letters of Emily Dickinson” in the Atlantic Monthly, Higginson claims that Dickinson’s second letter to him came with two more verses, “still in the same birdlike script.” They were: “Your riches taught me poverty” (F418) and “A bird came down the walk” (F359). According to Thomas Johnson’s note on letter 261, however, Higginson was incorrect. Analyzing the “folds in the letters and the poems,” Johnson argues that the enclosures must have been “There came a Day at Summer’s full” (F325), “Of all the Sounds despatched abroad” (F334), and “South Winds jostle them” (F98). Franklin argues that Dickinson enclosed “Your riches taught me poverty” in her fourth letter to Higginson, in July 1862. This week’s post explores the three poems Johnson claims came with the second letter, as well as the poems Higginson claims were included, despite the corrective. Though some poems may have been sent to him at another time, Higginson’s choice to mention them in his essay in the Atlantic demonstrates the profound effect they had on him. They are, as he writes, in

defiance of form, never through carelessness, and never precisely from whim, [exhibiting a] rare and delicate sympathy with the life of nature.

Additionally, we’ve decided to follow the lead of Dickinson scholars, who regard Dickinson’s letters as primary aesthetic and literary texts in their own right (rather than just sources of biographical information), and include this week’s letter among the poems as one of our primary texts.

Sources

Thomas Johnson’s Note on Letter 261

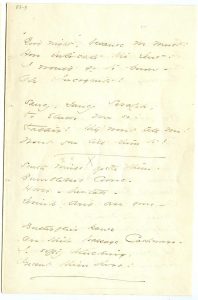

South winds jostle them (F98C, J86)

South winds jostle them -

Bumblebees come -

Hover – hesitate -

Drink, and are gone -

Butterflies pause

On their passage Cashmere -

I – softly plucking,

Present them here!

EDA manuscript: "Originally sent to Louise and Frances Norcross about summer 1859, now lost. Sent to Higginson on 25 April, 1862, now in BPL – Ms. Am. 1093(5) – p. 1; Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Rare Books and Manuscripts Collection, Boston, MA. First published in Poems (1891), 160, from the fascicle (C)."

Dickinson originally sent this poem to her cousins Louise and Frances Norcross with pressed flowers, about summer 1859. She then copied it into Fascicle 5 around 1861. She included a copy of it in her second letter to Higginson with pressed flowers on 25 April, 1862. It is clearly a “presentation” poem meant to accompany a pressed flower or small bouquet and Dickinson might have meant it as a gift for Higginson, who wrote eloquently about flowers and birds in several of his Atlantic Monthly essays. But could it also have been a rebuttal to the “surgery” he performed on the first four poems she sent?

It is an example of her free verse poetry, held together by some rhymes and the repetition of dimeter lines 2, 4, 8. But it’s not hard to see that Higginson might regard the “gait” or rhythm as “spasmodic” and certainly far from regular, though it captures the jostling of flowers by wind, bees, and butterflies.

The reference to “Cashmere” invites us to think of this poem in the terms set out by Mary Kuhn in her essay, “Dickinson and the Politics of Plant Sensibility,” which substantially enlarges the scope of Dickinson’s world. Kuhn points to another poem, “If I could bribe them by a Rose” (F176A, J179), which continues: “I'd bring them every flower that grows / From Amherst to Cashmere!” and observes:

The distance between Western Massachusetts and the Kashmir region of the Indian subcontinent—well over six thousand miles—is one that few in Dickinson’s lifetime would travel. The poet, however, traversed these miles within the poetic line. … The generative energy of this dimension of her writing has led to a turn in criticism that has unmoored Dickinson from the fixed radius around Amherst and even the United States. Dickinson’s ability to “telescope” place, as Christine Gerhardt puts it, is often particularly notable in the floral language she evokes over the course of her poetic career, because Dickinson was keenly aware that flowers simultaneously comprised the local garden and circumnavigated the globe. This motion resists the explanatory power of conceptual categories like the local or national, and Dickinson’s political engagement makes fuller sense when we consider how plants function within an international framework. Dickinson’s poems can suggest how middle-class horticultural enterprises were facilitated by colonial botanical pursuits, and how the projects of the home gardener were tied to imperial designs.

Sources

Kuhn, Mary. “Dickinson and the Politics of Plant Sensibility,” ELH 85.1 Spring 2018: 141-70, 143-44.

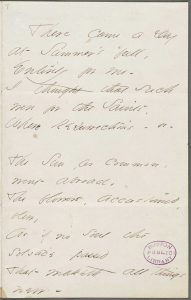

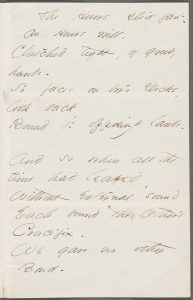

There came a Day at Summer’s full (F325D, J322)

There came a Day

at Summer's full,

Entirely for me –

I thought that such

were for the Saints,

Where Resurrections – be –

The Sun, as common,

went abroad,

The flowers, accustomed,

blew,

As if no soul the

solstice passed

That maketh all things

new –

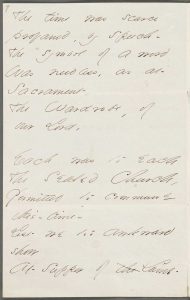

The time was scarce

profaned, by speech –

The symbol of a word

Was needless, as at

Sacrament,

The Wardrobe, of

our Lord –

Each was to each

The Sealed Church,

Permitted to commune

this – time –

Lest we too awkward

show

At supper of the Lamb.

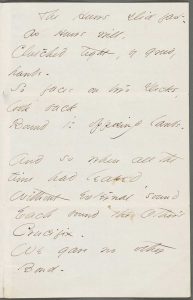

The Hours slid fast -

as Hours will,

Clutched tight, by greedy

hands –

So faces on two Decks,

look back,

Bound to opposing lands –

And so when all the

time had leaked,

Without external sound

Each bound the Other's

Crucifix –

We gave no other

Bond –

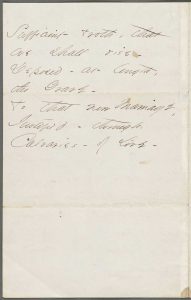

Sufficient Troth, that we shall rise –

Deposed – at length, the Grave –

To that new Marriage,

Justified – through Calvaries – of Love –

EDA manuscript: "Originally in BPL – Ms. Am. 1093(7) – p. 1; Courtesy of Boston Public Library, Rare Books and Manuscripts Collection, Boston, MA. First published in Scribner's Magazine, 8 (August 1890), 240, without stanza 4, from the copy to Susan Dickinson ([E]). Lavinia Dickinson protested this publication, and Mabel Todd pointed out that “sail” in line 7 was a misreading for “soul” (Bingham, AB, 59, 149n). With the permission of Scribner’s the poem was included in Poems (1890), 58-59, but the text itself derived from the fascicle (C), with the first word of the last line concluding the penultimate one; all the alternatives had been adopted (in accord with Dickinson's revisions), “revelations” adopted as the revision for line 4, and stanza 4 restored. Although a facsimile of the retained copy (B) was included in Poems (1891) to verify the correctness of “soul” in line 7, the text in Collected Poems (1924), 152-53, reverted to “sail,” based upon the annotation in Susan’s copy of Poems (1890)."

Originally published in Scribner’s Magazine in 1890 under the editorial title “Renunciation,” “There Came a Day at Summer’s Full” was one of the three poems that Johnson argues Dickinson sent along with her second letter to Higginson. In addition to the version she sent to Higginson, Dickinson penned two other variant versions: one included in Fascicle 13, and one she sent to Susan Dickinson. As Susan Leiter notes, the poem is distinguished from Dickinson’s other spiritual poems for its unambiguous “tone of assured belief,” marked by its regular meter, rhyme, syntax, and narrative arc. The last phrase, “Calvaries – of Love,” aptly captures Dickinson’s awareness of the suffering and sacramental nature of love.

Richard Sewall’s reading of the poem calls attention to its mastery of form, which Higginson considered defiant if not careless. Sewall writes,

the total journey of the poem, from a lovely summer day with sun and flowers to the beatific vision won through loyalty and suffering, is achieved with modulation and control.

Although Higginson regularized many of Dickinson’s posthumously published poems, his editing of “There came a day” was relatively sparse.

In terms of occasion, Sewall speculates that the poem could be

commemorating a farewell meeting, perhaps with [Reverend Charles] Wadsworth (whose 1860 visit was, however, in March); or with Samuel Bowles, who at least came to Amherst for many a Commencement in August; or, going further back, with Ben Newton, her first Tutor.

Countering this heteronormative reading, Martha Nell Smith argues that the love object here might be Susan Dickinson. Smith considers “There came a day” as one of a large group of Dickinson's “Calvary of Love” poems, which she made fair copies of in the early 1860s. While these poems “all emphasize a love crucified” and are full of suffering, several of them, like this poem, use imagery to “show lovers who are equals.” Thus, Smith argues,

they do not reflect the hierarchy of heterosexual relations in patriarchy, but the sameness and equality of lesbian relations.

Another approach is to consider this poem in the light of Dickinson's decision to write to Higginson and enclose her poems. It may have been, Sewall argues,

Dickinson’s way of dramatizing her ultimate determination to be a poet, the culminating moment, perhaps, of the long way she had come since the early premonitions in letters to Abiah Root and Jane Humphrey.

Sources

Sewall, Richard B. The Life of Emily Dickinson, 1974, 552-53.

Leiter, Sharon. Critical Companion to Emily Dickinson: A Literary Reference to Her Life and Work. New York, NY: Facts on File, 2007, 195.

Smith, Martha Nell. Rowing in Eden: Rereading Emily Dickinson. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1992: 37-38.

For a fascinating exploration of the various versions of the poem, see Carolyn Vega, “The Realm of Fox: The Dispersal of Emily Dickinson’s Manuscripts” in The Networked Recluse: The Connected World of Emily Dickinson. Amherst: Amherst College Press, 5-12.

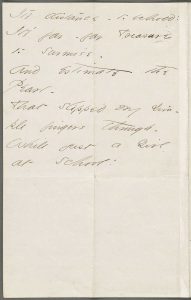

Of all the Sounds despatched abroad (F334 B, J321)

Of all the Sounds

despatched abroad,

There's not a Charge

to me

Like that old measure

in the Boughs -

That phraseless Melody -

The Wind does – working

like a Hand,

Whose fingers Comb

the Sky -

Then quiver down – with

tufts of Tune -

Permitted Gods, and me -

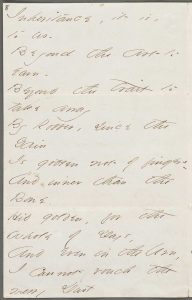

Inheritance, it is,

to us -

Beyond the Art to

earn -

Beyond the trait to

take away

By Robber, since the

Gain

Is gotten not of fingers -

And inner than the

Bone -

Hid golden, for the

whole of Days,

And even in the Urn,

I cannot vouch the

merry Dust

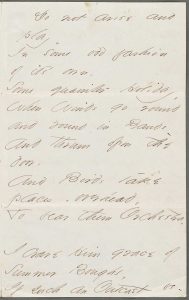

Do not arise and

play,

In some odd fashion

of it's own,

Some quainter Holiday,

When Winds go round

and round in Bands -

And thrum opon the

door,

And Birds take

places, overhead,

To bear them Orchestra.

I crave Him grace of

Summer Boughs,

If such an Outcast be -

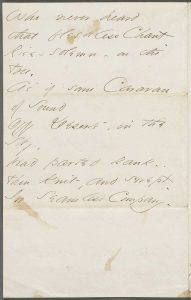

Who never heard

that fleshless Chant -

Rise – solemn – on the

Tree,

As if some Caravan

of Sound

Off Deserts, in the

Sky,

Had parted Rank -

Then knit, and swept -

In Seamless Company -

EDA manuscript: "Originally sent to Higginson on 25 April, 1862; now in BPL – Ms. Am. 1093(6) – p. 1; Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Rare Books and Manuscripts Collection, Boston, MA. First published in Higginson, Christian Union, 42 (25 September 1890), 393, in part, as two eight-line stanzas, from his copy (B) but with readings from the fascicle (A). Poems (1890), 96-97, in part, from the fascicle (A), as five stanzas of 4, 4, 4, 4, and 5 lines; the alternative for line 8 was adopted."

Dickinson copied this poem into Fascicle 12 in early 1862. It is a long poem for Dickinson and the hymn form is fairly regular, 8 line stanzas of 8686 loosely rhyming abcb dcec, though that breaks down in the later stanzas. Its theme is the action and effect of the wind, a favorite subject of the Romantic poets: think Shelley’s “Ode to the West Wind,” Keats’ “The Winter’s Wind,” Wordsworth’s “Surprised by Joy,” Coleridge’s “The Eolian Harp.” This last was a favorite trope of the Romantics: a stringed instrument placed in a window and played upon by the wind to make music not by human hands. They regarded this as an image of the poet’s divine inspiration. There is one in the parlor window at the Homestead.

Cristanne Miller calls our attention to the “Orientalist metaphor” of the last stanza, which

likens the moment of hearing this “solemn” natural music to … caravans bringing precious goods to desert dwellers … the wind brings transitory inspiration of its “Tune” to the poet.

While these “tropes of the East” connote exoticism and inspiration, we can also read them in Mary Kuhn’s terms, described in the commentary on “South Winds jostle them” (F98C, J86) as resisting the local and domestic scale often associated with Dickinson’s poems. Perhaps Dickinson wanted to show Higginson that she could handle a poetic subject favored by near contemporary male poets, and that she could give this theme an unusual and unique spin, which also indicated the global scope of her imagination.

Sources

Miller, Cristanne. Reading in Time: Emily Dickinson in the Nineteenth Century. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2012, 132.

A Bird Came down the Walk (F359/J328)

A Bird came down the Walk –

He did not know I saw –

He +bit an Angleworm in halves

And ate the fellow, raw,

And then he drank a Dew

From a convenient Grass –

And then hopped sidewise to the Wall

To let a Beetle pass –

He glanced with rapid eyes

That hurried all around –

They looked like frightened Beads, I thought –

He stirred his Velvet Head

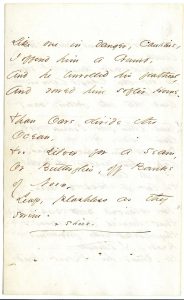

Like one in danger, Cautious,

I offered him a Crumb

And he unrolled his feathers

And rowed him softer home –

Than Oars divide the Ocean,

Too silver for a seam –

Or Butterflies, off Banks of Noon

Leap, plashless as they swim.

+shook

EDA manuscript: "Originally in Amherst Manuscript #fascicle 85. Courtesy of Amherst College, Amherst, MA. First published by Higginson, Atlantic Monthly, 68 (October 1891), 446-47, from the lost copy to him ([A]). Poems (1891), 140-41, from the fascicle copy (C), with the alternative not adopted."

Franklin argues that Dickinson sent a copy of this poem to Higginson in a letter dated August 1862, and copied a version into Fascicle 17 around that time. In the Atlantic Monthly, Higginson claims that “A Bird Came down the Walk” exhibits

what had already been visible, a rare and delicate sympathy with the life of nature

—a sympathy that may have garnered “more distinct praise or encouragement” in his response to Dickinson’s second letter.

Higginson decided to publish and comment on “A Bird” because he saw in it what Helen Vendler calls its “aesthetic ecstasy” in terms of form and soundscape. Cynthia Wolff calls attention to this quality as well, noting the

misfit between the categories available to the speaker and those that appear to be relevant to the “Bird.”

This poetic misfit between language and the bird results in a “failure to capture and organize the essence of the event,” which allows the poem to invoke “nature’s impenetrable enigma.”

Higginson may have been impressed by Dickinson’s “delicate sympathy” in writing about nature, but the poem also showcases her versatility with form. “A Bird” is written in quatrains of 6686 syllable length, rhyming abcb. Her mastery of form, however, emerges in the fourth stanza, which marks a rupture with the pattern, extending line length to 7676 syllables, invoking what Wolff calls the “danger” and unknowability of nature and writing about it. Dickinson is well aware of the inadequacy of language to describe nature, even on the micro-scale, but her sensitivity to form and its imperfection allows the poem to imitate that imprecision on the page.

Because form is so central to this poem’s conceit, we discussed it in the February 5-11 post on “Meter,” which addresses the intricacies of form in more detail.

Sources

Vendler, Helen. Dickinson: Selected Poems and Commentaries. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University, 2010, 160.

Higginson, Thomas Wentworth. “Emily Dickinson’s Letters,” The Atlantic. October 1891.

Wolff, Cynthia G. Emily Dickinson. New York: Knopf, 1986, 488.

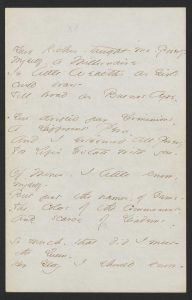

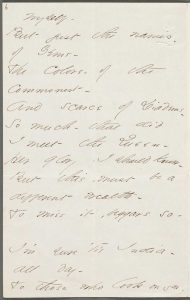

Your riches taught me poverty (F418B, J299)

Your Riches, taught

me, poverty –

Myself a Millionaire –

In little wealths – as

Girls could boast –

Till broad as Buenos –

Ayre –

You drifted your Do –

minions –

A different Peru –

And I esteemed all

poverty –

For Life's Estate, with you –

Of Mines, I little know, myself –

But just the names -

of Gems –

The Colors of the

commonest –

And scarce of Diadems –

So much – that did

I meet the Queen –

Her glory – I should know –

But this – must be a

different wealth –

To miss it, beggars so –

I'm sure 'tis India -

all day –

To those who look on you –

Without a stint -

without a blame –

Might I – but be the

Jew!

Im sure it is Golconda –

Beyond my power to deem –

To have a smile for

mine, each day –

How better, than a Gem!

At least, it solaces

to know –

That there exists – a

Gold –

Although I prove it

just in time

It's distance – to behold!

It's far – far Treasure

to surmise –

And estimate the

Pearl –

That slipped my sim –

ple fingers through –

While just a Girl

at school!

EDA manuscript: "Originally in BPL – Ms. Am. 1093(11) – p. 1; courtesy of Boston Public Library. First published in Higginson, Atlantic Monthly, 68 (October 1891), 446, from the copy to him (B); Poems (1891), 91-92, from the fascicle (C)."

Though Johnson points out that it is unlikely Dickinson actually included “Your riches taught me poverty” in the second letter to Higginson, and Franklin argues she enclosed it in her fourth letter written in July, it clearly left an impression on him. We know for certain she sent the poem to Susan Dickinson in 1862 with the heading “Dear Sue,” leading Susan Leiter to speculate that it recalls a

saying good-bye… to their girlhood romance, which, by 1862, had existed only in memory for quite some time.

If we imagine Sue as the subject of the poem, we see how Dickinson associates an energized diction with her. She writes of far-off, inaccessible locales—“Buenos Ayre,” “Peru,” “India”—and precious materials—“Diadems,” “Gem!,” “Gold,” “Treasure,” “the Pearl”—and calls attention to her childhood friend’s drifting “Dominions,” a “different” Peru, “a different wealth.”

Dickinson’s references to wealth and poverty, as well as a litany of precious objects, suggest that the poem filters her feelings toward Sue through the invocation of value. As Joan Burbick points out:

Dickinson often analyzes desire through economic tropes that ultimately determine the “cost of longing.” … Her work is never far from describing the tension of delayed desire as well as the horror of deprivation. In her quest for adequate expressions of delight, spectres of regulation stalk the poetry… But most provokingly, they figure as economic metaphors that imply a system of controlled “values.” Desire is often encased in a “costly” standard of measure that robs the body of delight.

In his essay in the Atlantic Monthly, printed in October of 1891, Higginson responded to the poem and recognized Dickinson's brilliant intentionality:

Here was already manifest that defiance of form, never through carelessness, and never precisely from whim, which so marked her. The slightest change in the order of word—thus, “While yet at school, a girl”—would have given her a rhyme for this last line; but no; she was intent upon her thought, and it would not have satisfied her to make the change.

Sources

Burbick, Joan. “Emily Dickinson and the Economics of Desire.” American Literature, vol. 58, no. 3, 1986: 361–378, 363-64.

Higginson, Thomas Wentworth. “Emily Dickinson’s Letters” The Atlantic Monthly. October 1891.

Leiter, Sharon. Critical Companion to Emily Dickinson: A Literary Reference to Her Life and Work. New York, NY: Facts on File, 2007, 234-35.

Dickinson’s Letter to Higginson, 25 April 1862 (L261)

25 April 1862

Mr Higginson,

Your kindness claimed earlier gratitude-but I was ill-and write today, from my pillow.

Thank you for the surgery-it was not so painful as I supposed. I bring you others-as you ask-though they might not differ-

While my thought is undressed-I can make the distinction, but when I put them in the Gown-they look alike, and numb.

You asked how old I was? I made no verse-but one or two-until this winter-Sir-

I had a terror-since September-I could tell to none-and so I sing, as the Boy does by the Burying Ground-because I am afraid- You inquire my Books-For Poets-I have Keats-and Mr and Mrs Browning. For Prose- Mr Ruskin-Sir Thomas Browne-and the Revelations. I went to school-but in your manner of the phrase-had no education. When a little Girl, I had a friend, who taught me Immortality-but venturing too near, himself-he never returned-Soon after, my Tutor, died-and for several years, my Lexicon-was my only companion-Then I found one more-but he was not contented I be his scholar-so he left the Land.

You ask of my Companions Hills-Sir-and the Sundown-and a Dog-large as myself, that my Father bought me-They are better than Beings-because they know-but do not tell-and the noise in the Pool, at Noon – excels my Piano. I have a Brother and Sister – My Mother does not care for thought-and Father, too busy with his Briefs – to notice what we do – He buys me many Books – but begs me not to read them-because he fears they joggle the Mind. They are religious-except me-and address an Eclipse, every morning-whom they call their “Father.” But I fear my story fatigues you-I would like to learn-Could you tell me how to grow-or is it unconveyed-like Melody-or Witchcraft?

You speak of Mr Whitman-I never read his Book-but was told that he was disgraceful-

I read Miss Prescott's "Circumstance," but it followed me, in the Dark-so I avoided her-

Two Editors of Journals came to my Father's House, this winter- and asked me for my Mind-and when I asked them "Why," they said I was penurious – and they, would use it for the World -

I could not weigh myself-Myself-

My size felt small- to me- I read your Chapters in the Atlantic- and experienced honor for you-I was sure you would not reject a confiding question-

Is this- Sir-what you asked me to tell you?

Your friend,

E – Dickinson.

Following the lead of Jane Donahue Eberwein and Cindy MacKenzie, we have decided to include Dickinson’s second letter to Higginson along with the poems for this week, and will continue to include letters in subsequent weeks, tracing Dickinson’s literary relationship with Higginson and others. Though scholars have so often mined Dickinson’s letters for biographical details, there is an urgent call to treat them as primary literary texts. Eberwein and MacKenzie make the case for doing so in the foreword to a collection of critical essays titled Reading Emily Dickinson’s Letters (2011):

It took, however, largely until the second half of the twentieth century before Dickinson’s letters were recognized as literary works of art in their own right—rather than as mere biographical or cultural background materials for her poems. This turn in reception emerged from the premise that Dickinson’s correspondence constitutes her only “published” form of writing, her “letter to the world” that she was willing to share with an audience. While Dickinson left her poems (individual poems as well as those collected in fascicles) in various states of (in)completion, often featuring multiple variants and unresolved alternative readings, it was her correspondence that she finalized and specifically prepared for circulation among friends and family members.

We’ve included a commentary on the letter in This Week in Biography, but as Eberwein and MacKenzie point out, the letter deserves to be included here as a part of Dickinson’s “central form of public artistic expression.” The letters, they argue, deserve the same sort of critical attention afforded to Dickinson’s poetry. In particular, the letters are of interest as primary texts to feminist scholars, who turned their

attention to socially transgressive aspects of her letters, and paid increased attention to female correspondents such as Susan Dickinson and Elizabeth Holland.

Sources

Eberwein, Jane Donahue and Cindy MacKenzie. Reading Emily Dickinson's Letters: Critical Essays. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2009. Project MUSE.