As we approach the season of Thanksgiving, or more correctly, Indigenous Peoples' Day, we often look back at what and who we have to give thanks for. During this week in 1862, The Springfield Republican noted the advent of the holiday in New England but found very little to rejoice in. Rather, it issued this dire warning:

In this hour of plenty we may discern the skeleton finger of want [brought on by the Civil War, whose] heavy burden of debt, scarcity, and high prices are but just beginning to be felt,

and would be felt by the neediest first. The only cause for rejoicing SR could find was that “our community” does not yet feel the economic deprivations caused by the War. But by many accounts, people were already living emotionally and spiritually in the aftermath of the bloodiest autumn on record.

Many readers consider Dickinson to be a poet particularly suited for this “posterior” moment of trauma, a poet of “That after Horror,” a poet “living in the aftermath.” Scholar David Porter argues that

Dickinson claimed the aftermath as her special territory. It was as much her fecund ground as Manhattan was Whitman’s or Paterson was Williams’s. In that realm of least promise she found the performing imagination.

Dickinson's poetry gives unique and unsettling voice to what happens after particular experiences or crises, and how a shattered soul or mind or life manages to go on—or not. We find that “aftermath” has several profound and different meanings in her canon of work: the aftermath of personal emotional crisis, the aftermath of a loss of faith, the aftermath of battles and death tolls of the Civil War. In some way, Dickinson’s entire being as a poet occupies the space of aftermath as her major body of work was only discovered and subsequently published after her death. This week, we explore Dickinson’s poetry of aftermath to discern its parameters and driving energy, to see what possibly comes “after.”

“The Skeleton Finger of Want”

Springfield Republican, November 22, 1862

Progress of the War, page 1

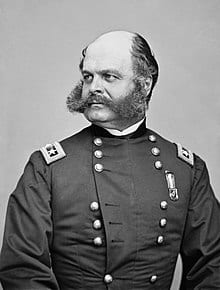

“With scarcely a ripple of agitation and not the slightest factious demonstration, the army and the people have acquiesced in the changes of command in the army of Virginia, and Gen. Burnside has commenced his administration by a change of base from Alexandria to Fredericksburg. This indicates that there is a real purpose to march at Richmond.”

Foreign Affairs, page 1

“There is nothing particularly new in regard to the revolution in Greece. King Otto has no intention of trying to obtain the reins of government again and has retired with all the dignity possible to one in his position. The larger part of the insurgents has declared in favor of a monarchical form of government, but there is a strong party in favor of a republic, formed in connection with some of the nearest Turkish provinces. Russia is said to favor the latter plan, but it is not expected the other European governments will consent to it, and the great question now is, who shall be the next king.”

A Cheap Enjoyment, page 2

“None of us can afford to be miserable, or even anxious and desponding. Enjoyment is a necessity of healthful life, and one that in the sternest of times we can by no means spare. Yet we may well dispense with costly pleasures. During the coming winter many of us will be content to eat plainer food and wear cheaper clothing than in more prosperous years, and we may find that the retrenchment brings no loss of health or comfort. So too our amusements may be chosen with regard to economy and lose no portion of their zest.”

Books, Authors and Arts, page 7

“The present is an age of words rather than thoughts. Original thoughts are very rare; original expressions are very common. Nothing is easier than to say that the sky is a cupping-glass and battle-fields are the spots where the blood is drawn. There is no thought in this, for it means nothing; it is only a metaphorical way of saying that men bleed beneath the sky, a statement with which we are all sufficiently familiar, although we have never yet met it in the disguise of a surgical trope. The greater part of modern poetry and the weaker part of its prose consists in clothing common-place ideas in an outlandish garb of words.”

Hampshire Gazette, November 25, 1862

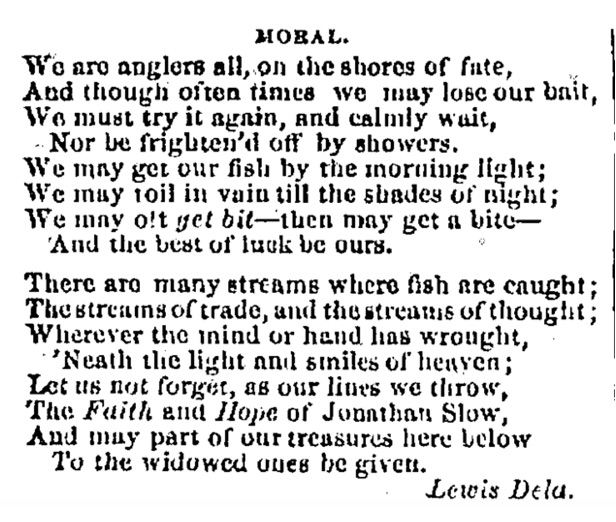

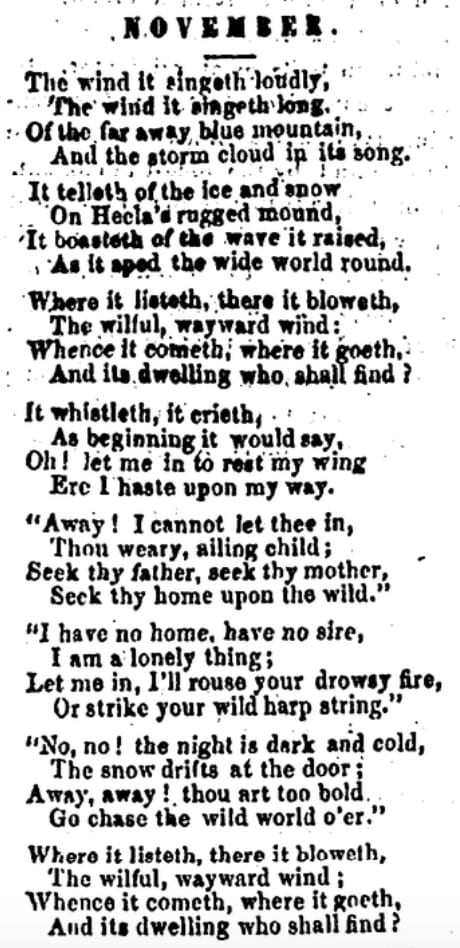

Original Poetry, page 1 [Found under the title “October” in Beautiful Poetry. A Selection of the choicest of the Present and the Past, for 1857, selected by the editors of The Critic, London Literary Journal, London: Critic Office, 1857. p 176, with the note: Taken from The Farmer’s Almanac, where it appeared anonymously.]

Individualism, page 1

Individualism, page 1

“Every man is individually responsible to God for his actions. He is born apart, he lives apart, apart he dies; and at the judgment-seat of Christ, for himself, he stands or falls. Man is a distinct being, and consequently cannot shift his responsibility. He thinks for himself, chooses for himself, and for himself he acts. Man is swayed by influences; but no matter how great those influences may be which prompt him to action, ever and anon those acts are regarded as his own, and for them he is accountable to the Almighty God.”

Thanksgiving, page 2

“We stand at the threshold of a long and dreary winter. The coming of the inclement season is fitly ushered in by our annual Thanksgiving. On Thursday next we celebrate this New England anniversary with 18 of our sister states. In this hour of plenty we may discern the skeleton finger of want. The civil war that has been raging for the past eighteen months is pressing harder and harder upon us. Its heavy burden of debt, scarcity, and high prices are but just beginning to be felt. While we shudder at the immediate future, we can but rejoice that so much of competence has been spared to our community, that we are able to meet with comparative indifference the grievous load that has been forced upon us.”

Atlantic Monthly, November 1862

“Wild Apples” by Henry David Thoreau

“Early apples begin to be ripe about the first of August; but I think that none of them are so good to eat as some to smell. One is worth more to scent your hand-kerchief with than any perfume which they sell in the shops. The fragrance of some fruits is not to be forgotten, along with that of flowers. … There is thus about all natural products a certain volatile and ethereal quality which represents their highest value, and which cannot be vulgarized, or bought and sold. No mortal has ever enjoyed the perfect flavor of any fruit, and only the god-like among men begin to taste its ambrosial qualities. For nectar and ambrosia are only those fine flavors of every earthly fruit which our coarse palates fail to perceive,—just as we occupy the heaven of the gods without knowing it. …

Going up the side of a cliff about the first of November, I saw a vigorous young apple-tree, which, planted by birds or cows, had shot up amid the rocks and open woods there, and had now much fruit on it, uninjured by the frosts, when all cultivated apples were gathered. It was a rank wild growth, with many green leaves on it still, and made an impression of thorniness. The fruit was hard and green, but looked as if it would be palatable in the winter. Some was dangling, on the twigs, but more half-buried in the wet leaves under the tree, or rolled far down the hill amid the rocks. The owner knows nothing of it. … Most fruits which we prize and use depend entirely on our care. Corn and grain, potatoes, peaches, melons, etc., depend altogether on our planting; but the apple emulates man's independence and enterprise.”

“What is to be is / best descried / When it has also been–”

Dickinson’s special relationship to aftermath and trauma has long been acknowledged by readers and explored by scholars. For example, probably her best-known poem on this theme, “After great pain, a formal feelings comes–” (F372, J342), dated to 1862, manages to describe this psychic phenomenon with uncanny exactitude but does so in imagery that speaks universally about many kinds of pain. Critic Robert Weisbuch observes that Dickinson’s many poems about the aftereffects of this kind of trauma

say precisely nothing about Dickinson’s unique experience. But they do afford an extraordinary comfort precisely because different people can bring their trouble to them.

Some readers, though, offer more specific speculations about Dickinson’s landscape of aftermath. For example, Chloe Marnin reads Dickinson’s suite of volcano poems, explored in detail in an earlier post, as a poetic account of the “aftermath of human emotions” due to repression. There is evidence that Dickinson did not communicate her deepest feelings and experiences to her family. In a poem dated to 1877 and addressed to “Katie,” Catherine Scott Anthon, who visited Amherst that year, Dickinson wrote:

I shall not

murmur if at last

The ones I loved

below

Permission have

to understand

For what I shunned

them so –

Divulging it would rest my Heart

But it would

ravage their's –

Why, Katie, Treason

has a Voice –

But mine – dispels -

in Tears. (F 1429, J1410)

Labeling the telling of the source of her pain as “Treason,” a profound betrayal of some family trust or sense of loyalty, suggests the enormity of the pressure Dickinson felt to remain silent.

Physician Isabel Legarda picks up on imagery of this sort, citing a study that argues that Dickinson, as well as other notable historical figures,

developed symptoms consistent with post-traumatic stress disorder in the aftermath of repeated potentially traumatizing events.

Rejecting the airbrushed “myth” of the woman in white and even contemporary versions of Dickinson that gloss over the darkness in her work, Legarda lists over fifty poems in which she finds evidence of trauma, including some kind of sexual assault. She argues that this “truth,” although impossible to prove, is important for readers, and perhaps even more so in the age of the #MeToo movement.

Other scholars see the trauma Dickinson anatomizes as brought on by the horror of the Civil War. David C. Ward, for example, calls Dickinson, along with contemporary poet Walt Whitman, “the great American poets of the Aftermath of the Civil War:”

Dickinson shows us the aftermath and the regret not only for the loss of life but of what war does to the living. Dickinson and Whitman show us two ways of working through the problem of how to mourn and how to gauge the effect that the war was having on Americans.

Ward references the poem “My triumph lasted till the drums” (F1212, J1227) dated 1872, which contains perhaps Dickinson's most concise description of her theory or practice of aftermath (highlighted in red):

My Triumph lasted

till the Drums

Had left the Dead

alone

And then I dropped

my Victory

And chastened stole

along

To where the

finished Faces

Conclusion turned

on me

And then I hated

Glory

And wished myself

were They.What is to be is

best descried

When it has also been -

Could Prospect

taste of Retrospect

The Tyrannies of

Men

Were Tenderer,

diviner

The Transitive

toward –

A Bayonet's contritionIs nothing to

the Dead -

Richard Brantley explains what Vivian Pollak labels Dickinson’s “post-experiential perspective” in her poems of “aftermath” through her intellectual and spiritual influences. Brantley places Dickinson in conversation with philosopher John Locke (1632-1704), naturalist Charles Darwin (1809-1882) and Methodist leader Charles Wesley (1707-1788) through the emotional and intellectual tutelage of the Rev. Charles Wadsworth (1814-1882), a man Dickinson dubbed “My Clergyman.” Brantley argues that Wadsworth opened Dickinson to the philosophy, technology and science of her day, which emphasized empiricism, experimentation and, particularly, experience. This “rhetoric of sensation,” as Mary Lee Stephenson Huffer calls it, led Dickinson to the “Despairing Hope” that categorizes her unique poetry of “aftermath.”

Reflection

Katrina Dzyak

Even more so than she is considered a poet of Death and Loss, Emily Dickinson, critics claim, is the poet of After: Aftermath, Afterward, Thereafter. Loss entails the fact of After, but, for Dickinson, After is not necessarily at or equal to a loss, lacking, it is not a gutted or inert space, inarticulate and inarticulable, absent of a presence, a being, or some vitality that once was. For Dickinson, After is the beginning, not as in re-generation, but generation itself and an amplified one. After is where Life begins, which is to say that for Dickinson, Loss and After beget Life and what is thought to be alive before a Loss and, thus, before an After, is in fact only posing as such.

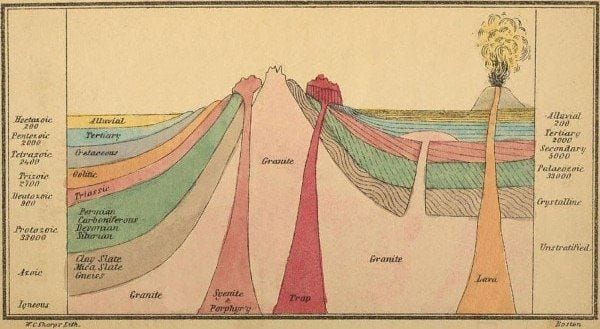

But Dickinson does not make this claim purely metaphorically. Her engagement with 18th and 19th century theories from natural science, biology, and the philosophy of science, as they emerged as disciplines during her lifetime, steer her towards this troubling and liberating claim that in Loss, Death, separation, and After, there is Life, by putting the biological body made of cells and organs at the fore of her thinking and at the fore of her systemic investigation in the matter, conceptual and material, of what comes after Loss, when Loss means separation and a divided self.

Dickinson’s poem, “I breathed enough to take the Trick – ” (F308), dated to 1862, guides us through this formula and the procedure Dickinson’s speaker undergoes and follows to make clear how Life is generated by the Loss, separation, division of something that creates an Aftermath to a Before. The poem’s first line, “I breathed enough to take the Trick – ,” immediately establishes a threshold, a dividing line. “I breathed enough,” repurposes what is most fundamental and necessary to life, breathing, as not a question of all or nothing, breathing or not breathing, Life or Death, but a question of limits, introducing breath and, thus, life and, thus, death, as spread over a spectrum and existing in gradations. The question, How much breath is enough? asks us to consider how we might get by with less or how it might be possible for breath to exist in or as excess.

Insofar as “enough” means minimum, “enough” motions more so towards the possibility of not enough, towards lack, Loss, Death, than it does towards an excessive energy or towards a bounding vitality. How much breath is enough for what? The line offers “to take the Trick – ,” which could be read as to grab at the Trick, to possesses the Trick, to move the Trick and, thus, to make the Trick come, come closer, come into being, come sexually, reproductively, generatively. Regardless, “to take the Trick -”, means we will never know the inflection of “take,” because we will never know where the Trick was taken, how it was taken, where it was taken. What we know is that the threshold of “enough” takes “the Trick” and makes it different, puts it differently, transitions it from Before to After.

The next line, “And now, removed from Air -,” repeats the poem’s preoccupation with division and the here, there, Before, After times and spaces it works between and through. “And now” makes present that we are “now” After, that there was a Before that is not now, “now.” “And now, removed from Air” further establishes a movement away from here or Before to an elsewhere that is After. At first, “removed from Air” suggests Death, only Death would be something more like Air removed. “Removed from Air,” insofar as “Air” denotes what would be familiar, what would, generally be Earth, moves us either celestially or molecularly, where “Air” is either absent, in intergalactic orbit, or unformed, absent as a unified substance within or as matter that relies on it to live, absent within us, who “take” it from outside, who breathe it in and make it part of us, make it generate us.

At either the cosmic or molecular level, then, “I,” “removed from Air – ” “simulate the Breath, so well – ,” which is to say that in this unearthly, unfamiliar space that is a legacy of the division that made it distinct, an After to the Before of life on Earth as the speaker knows it, “I simulate the Breath,” or pretend to breathe, “so well – ,” well “enough” to “Trick” “That One” of the next line. “I” simulate “the Breath,” or unity, homogeneity, the convergence of parts made by the mixture “Air,” that “I” breathe only what “I” need and “Trick” “That One,” or those who see not the mixture, parts, divisions between self and “Air” that make “That One” them, but who see merely “That One” as already “quite” surely its own package and matter, their own self as blended and contained, not part of a Before “Air” or After “Air” complex.

A dedicated sleuth of all vogue academic topics at the time, indicated by her library and the criticism contained in her letter correspondences, Dickinson here in F308 works out the ways a substance, “Air,” that is “That One” thing that appears truly homogeneous, “That One” thing that we need to preserve our own boundaries, to remain contained as one, as ourselves, alive, “Air,” is, in fact, according to 19th-century scientists John Dalton’s Dalton’s Law, a mixture, an unsteady substance made of components whose relations are brokered by unreliable and dizzying particles unseen and, as of then, still only newly known. With this knowledge in mind, Dickinson, or her speaker, sensitive to the circulating substances within, Tricks herself or her audience, her community, into seeing her, this “I,” as indeed “One,” “That One,” who is not only homogeneous, contained, and singular, but “That One” in particular, that distinct, though whole, identity, the “I” who “breathed.”

But the speaker knows that there is a limit, a threshold to the stability of “That One,” where the exchange between particles that mix to make “Air” to sustain Life, relies necessarily on Loss, lost exchanges, lost relations, lost unity, unfulfilled mixtures, division, and its After. Within that loss, “The Lungs,” for example, “are stirless -, ” which is to say that they remain unstirred, or unmixed, not “That One” unified matter that accepts a united “Air” that drives life, but a space where “Air” has to and might fail to enter and be mixed into Life, not automatically part of the Life of the body of “The Lungs.” When the mixture of “Air” is unstirred in the cosmic space, or in the molecular space, or in “The Lungs,” where “Air” is still only coming into being as Life by discrete and disparate particles that might not always promise to mix, Life remains “stirless,” a spread of particles.

In F308, “The Lungs” further wait, “stirless,” because forever already divided as one and the other. Thus, we “must descend / Among the cunning cells – / And touch the Pantomime – Himself.” In other words, we must “descend” to or enter what is “stirless,” this division, enter the Under World, enter Death, what seems to be Death by or as this division, where we find “the cunning cells – ,” the separated and distinct bodies that have not mixed, joined, solidified into recognizable matter. There, we might try to mix the cells together, to push them into unity, to push Death back over the threshold and into Life. These efforts result only in our recognizing unity as Pantomime, an ebullient attempt to mime Life as singular. Greeting “the cunning cells,” we see that they “Trick” us, that they simultaneously separate and divide, self-combust, scattering, and generate, building. That is, in crossing the threshold that is their singularity, they divide, and in dividing, they make the particles mix, congregate and stir together to homogenize and find, as Air and as Body, a Self, “That One.” Cells are simultaneously Before and After.

Growing awareness since 1835, when German Botanist Hugo von Mohl observed dividing and expanding cells under a microscope, of these individuated compartments, bodies, that compete and congeal to form matter, culminates in widespread acceptance by the mid-19th-century among transatlantic science communities that omnis cellula ex cellula, all cells come from cells, the subtitle of German Physician Rudolg Virchow’s 1858 Die Cellularpathologie (Cellular Pathology) published in English in 1860. “That One” life that is, now we know, “Pantomime,” posing as “One” life, F308 insists, is only the result of “cunning cells,” whose division makes something that is not “That One,” but that is always “stirless” because of a constant flow of new materials within and into a body. Division and this flow further stimulate sensation, sensation that registered Life.

“How numb, the Bellows feels!,” the speaker exclaims, when pushing “Air” through a bag, compressing it in a “Bellows,” or through “The Lungs.” Life, sensation that “feels!,” emerges at the moment of estrangement, of division, when “Air” leaves the body in an exhale. Then, a “Himself,” any self, comes to the fore still “numb" from the recent division, the recent loss of “That One,” a recent touch of Death as singularity, but still as one who “feels!” The Aftermath of this division, brought on by the exhale, sets us up again for “I breathed enough,” the inhale that Tricks us once more into accepting that we are “That One.” But, the inhale-exhale divide, F308 explains, while it brings Life precariously close to Death at every breath, precariously close to numbness, insofar as this division, in and out, is paralleled by the “cunning cells,” when we greet these cellular particles who divide and multiply, we might lose our belief in “That One” and recognize Life as the After of Loss or division, indeed, of exhale but, more simply, of cell division.

Bio: Katrina Dzyak is a PhD candidate in the Department of English & Comparative Literature at Columbia University. She studies Early & Nineteenth Century American Literature and literatures of the Atlantic World. Her research interests include the history of Natural Science; the Medical Humanities; Ethnicity, Race, and Indigenous Studies; and Archive theory.

Sources

Overview

Porter, David. Dickinson: The Modern Idiom. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1981: 24.

History

Atlantic Monthly, November 1862

Hampshire Gazette, November 25, 1862

Springfield Republican, November 22, 1862

Biography

Huffer, Mary Lee Stephenson. Emily Dickinson's experiential poetics and Rev. Dr. Charles Wadsworth's rhetoric of sensation: the intellectual friendship between the poet and a pastor. Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press, 2007.

Legarda, Isabel. “Emily Dickinson’s Legacy is Incomplete without Discussing Trauma.” The Establishment. September 8, 2017

Marnin, Chloe. “The Imagery of Volcanoes in Emily Dickinson’s Poetry: The Psychology and Aftermath of Emotional Repression.” May 10, 2016.

Pollak, Vivian. Dickinson: The Anxiety of Gender. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1984, 202-03.

Ward, David C. “Walt Whitman, Emily Dickinson and the War That Changed Poetry, Forever.” smithsonian.com August 14, 2013

Weisbuch, Robert. “Prisming Dickinson; or Gathering Paradise by Letting Go.” The Emily Dickinson Handbook. Eds. Gudrun Grabher, Roland Hagenbüchle, Cristanne Miller. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1998: 197-223, 217.

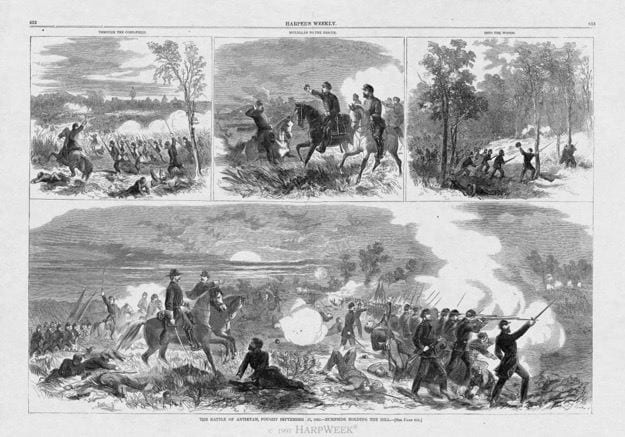

“The battle began with the dawn. Morning found both armies just as they had slept, almost close enough to look into each other’s eyes. … A battery was almost immediately pushed forward beyond the central woods, over a plowed field, near the top of the slope where the corn-field began. On this open field, in the corn beyond, and in the woods, which stretched forward into the broad fields like a promontory into the ocean, were the hardest and deadliest struggles of the day. … But out of those gloomy woods came suddenly and heavily terrible volleys—volleys which smote, and bent, and broke in a moment that eager front, and hurled them swiftly back for half the distance they had won. Not swiftly, nor in panic, any further. Closing up their shattered lines, they came slowly away—a regiment where a brigade had been, hardly a brigade where a whole division had been, victorious. They had met from the woods the first volleys of musketry from fresh troops—had met them and returned them till their line had yielded and gone down before the weight of fire, and till their ammunition was exhausted. …The field and its ghastly harvest which the reaper had gathered in those fatal hours remained finally with us. Four times it had been lost and won. The dead are strewn so thickly that as you ride over it you can not guide your horse’s steps too carefully. Pale and bloody faces are every where upturned. They are sad and terrible, but there is nothing which makes one’s heart beat so quickly as the imploring look of sorely wounded men who beckon wearily for help which you can not stay to give.”

“The battle began with the dawn. Morning found both armies just as they had slept, almost close enough to look into each other’s eyes. … A battery was almost immediately pushed forward beyond the central woods, over a plowed field, near the top of the slope where the corn-field began. On this open field, in the corn beyond, and in the woods, which stretched forward into the broad fields like a promontory into the ocean, were the hardest and deadliest struggles of the day. … But out of those gloomy woods came suddenly and heavily terrible volleys—volleys which smote, and bent, and broke in a moment that eager front, and hurled them swiftly back for half the distance they had won. Not swiftly, nor in panic, any further. Closing up their shattered lines, they came slowly away—a regiment where a brigade had been, hardly a brigade where a whole division had been, victorious. They had met from the woods the first volleys of musketry from fresh troops—had met them and returned them till their line had yielded and gone down before the weight of fire, and till their ammunition was exhausted. …The field and its ghastly harvest which the reaper had gathered in those fatal hours remained finally with us. Four times it had been lost and won. The dead are strewn so thickly that as you ride over it you can not guide your horse’s steps too carefully. Pale and bloody faces are every where upturned. They are sad and terrible, but there is nothing which makes one’s heart beat so quickly as the imploring look of sorely wounded men who beckon wearily for help which you can not stay to give.”