Thinking about grand themes like death and aftermath in Dickinson’s poetry, as we have done for the past couple of weeks, has inspired this week’s focus on a related and encompassing set of themes – time, temporality, and eternity. Several scholars have noted Dickinson’s obsession with time. For Sharon Cameron,

Dickinson's lyrics are especially caught up in the oblique dialectic of time and immortality.

In a moving essay on the subject, Peggy O’Brien considers Dickinson in relation to other poets, early and late, and finds:

Viewing Dickinson through the lens of her fixation on time reveals her absolute uniqueness. … Dickinson’s specificity about time, the way she makes it palpable and pressing, allows her to inhabit this metaphysical plane and bring her readers in their stubborn corporeality along with her in hers to it.

As we near the end of our year with Dickinson and the shortest day of the year, we tackle this significant theme of time, which is unmistakable in her writing, to see what she does with it around 1862.

Many readers chalk up Dickinson’s obsession with time to her Romanticism. But from the Calvinist Protestant tradition, Dickinson inherited a strong concept of time shaped by God and by ideas of salvation and immortality. In many of her poems, however, she questions this tradition and its notion of eschatology, the theory of the “end times.” The ideas about time Dickinson evolves in place of traditional Christian ones are challenging, sometimes contradictory, and often surprising for the way she adopts current philosophical and scientific thinking about time and space and anticipates modern philosophers of time. We will explore these challenges and also consider Dickinson’s relationship to time understood in terms of her own time, her historical context, and her deep engagement with time as meter and rhythm in her innovative poetry.

“Let But a Brilliant Genius Arise”

Springfield Republican, November 29, 1862

Progress of the War, page 1

“The expectations raised by the military movements of last week are disappointed. Gen. Burnside did not make the anticipated attempt to cut off the retreat of the rebel army to Richmond, and still remains on the north bank of the Rappahannock opposite Fredericksburg. The severe storm, spoiling the roads and producing great discomfort and not a little positive suffering in our half-sheltered army, is one cause of the delay; and another is found in the slow coach movements of the departments of supply at Washington.”

The Greek Revolution, page 2

“The late rebellion in Greece was universal. Never before, perhaps, has a whole people so unanimously elected a ruler, or set a reigning sovereign adrift. The citizens, the clergy, the army and the navy were all against King Otto, and he left the country he had lived in and governed for 80 years, without a voice raised in his favor, or hardly a friend to mourn his departure.”

Poetry, page 6

“The Trundle Bed.” [First copyrighted in 1860, “My Trundle Bed” was written by John C. Baker to be sung by Miss Lizzie Hutchinson of the Hutchinson family. For the full poem, see American Radio History, July 3, 1937. p. 11]. Books, Authors, and Arts, page 7

Books, Authors, and Arts, page 7

“We have a class of ambitious writers who imitate nobody but Harriet Prescott and Elizabeth Sheppard. These women possess real genius, but of a peculiar kind, and which often clothes itself in grotesque and extravagant forms. They are, therefore, the very last persons whose cast-off clothing can be supposed to be a general fit, and the unfortunate wights who gather up and adopt as a costume their fallen finery are seldom at ease in it and have all the disadvantages of caricatures of an exceptional original. Let but a brilliant genius arise whose rare gifts redeem his striking faults, who even takes advantage of them as foils, and hundreds of petty persons who have no remarkable gifts whatever will at once proceed to imitate what to them alone is inimitable and present a disgusted public with an abundance of life-size copies of their favorite’s defects.”

Hampshire Gazette, December 2, 1862

Mosquito Experience (from Henry Ward Beecher’s Eyes and Ears), page 1

“Much of the anxiety of business is mere mosquito-hunting. When I see a man pale and anxious, not for what has happened, but for what may happen, I say, ‘Strike your own face, do it again, and keep doing it for there is nothing else to hit.’ Everybody has his own mosquitos, that fly by night or bite by day. There are few men of nerves firm enough to calmly let them bite. Most men insist upon flagellating themselves for the sake of not hitting their troubles.”

Amherst, page 3

“Rev. C. L. Woodworth, chaplain to the 27th regiment, arrived at his home in Amherst on Friday evening week. He preached to his old congregation on the following Sunday, and will speak, to the citizens of Amherst, at the congregational church, this evening, giving a history of his experience in camp.”

Harper’s Monthly, November 1862

Editor’s Table, page 845

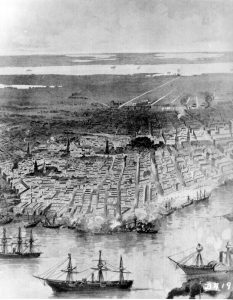

“We are now in the second year of the war, and this autumn, which is likely to bring with it signal events, cannot but urge upon us most significant thoughts. We are now in the third stage of our national crisis. Fort Sumter taught us that we are a people, and mean to stand by our national life; Bull Run convinced us that we must have an army, and gave us the most magnificent army on earth; the Army of the Potomac has shown us that we must have a government equal to the issue, and it is upon this imperative want that both the people and the army are now dwelling with intense emphasis. Why more efficiency in the Government is demanded, what are the chief causes of its recent inefficiency, and what is called for by the voice of the nation and is sure to have the nation’s favor and support, our readers may not need many words of ours to suggest.”

“I Never Knew how to Tell Time by the Clock”

For a poet and thinker obsessed with time, Dickinson had an awkward beginning with the practice of it. In a letter Thomas Higginson sent to his wife about his visit with Dickinson on August 16, 1870, he included this anecdote. Among the stories Dickinson shared, she told him:

I never knew how to tell the time by the clock until I was 15. My father thought he had taught me but I did not understand & I was afraid to say I did not & afraid to ask anyone else lest he should know (L 342b).

Clearly, telling time by the clock was an important aspect of Dickinson's father’s tutelage, as, no doubt, was the virtue of punctuality (did lawyers think in terms of billable hours back then?). But it didn’t stick. It is interesting to speculate just how the teenaged Dickinson learned to read clocks.

We know Dickinson absorbed religious concepts of time and eternity from her Protestant upbringing but she did not seem to take comfort in them. In 1848, she wrote to her good friend Abiah Root:

Does not Eternity appear dreadful to you? … it seems so dark to me that I almost wish there was no Eternity (L 23).

According to scholars, aspects of the religious notion of time and eternity shaped what literary theorist Georges Poulet, in an essay from 1956, diagnoses as Dickinson's dilemma:

All her spiritual life and all her poetry are comprehended only in the determination given them by two initial moments, one of which is contradicted by the other, a moment in which one possesses eternity and a moment when one loses it.

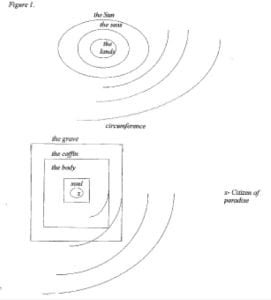

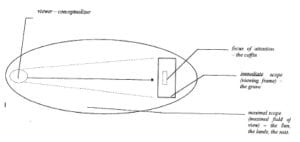

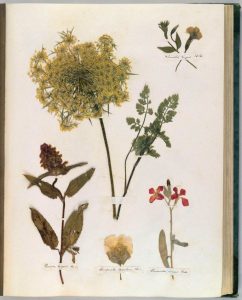

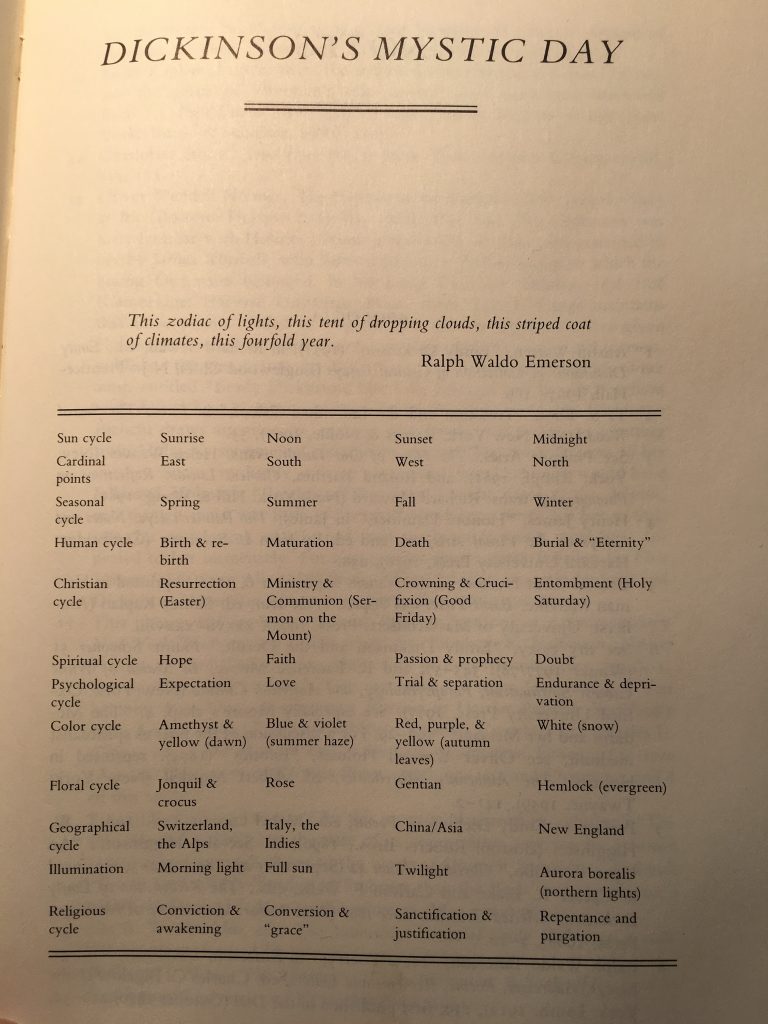

Expanding on the ideas of Rebecca Patterson, who explored Dickinson’s spatial imagery of the four cardinal points of the compass, Barton Levi St. Armand contends that Dickinson solved this dilemma by imagining time not as a clock but as a “sundial” and by organizing “very personal and much more elaborate correspondences” in relation to the four major corners of the dial into a schema he calls Dickinson’s “mystic day,” which we discussed earlier in our post on Spring:

from Barton Levi St. Armand, Emily Dickinson and her Culture, p. 317

About the dilemma posed by time and eternity, St. Armand argued:

The mystic day was a means of solving this dilemma by merging these two moments and collapsing time into eternity, though such a method of necessity brought with it infinite agony or infinite ecstasy, depending on one’s placement in the houses of her transcendence.

As this handy chart above illustrates, the four directions correspond to the two solstices (noon, midnight) and two equinoxes (sunrise, sunset), as well as the human cycle of growth, the religious cycle of Christ’s life, the spiritual and religious cycles of faith, the four seasons, colors, psychology, flowers, geography and illumination. The effects of the sun, its light and its position in the sky, play a major role in this “mystic day.” The sun itself comes to represent a lover-deity-Master-Christ-figure St. Armand calls “Phoebus,” another name for the Greek god Apollo, charged with managing the sun's movement in the sky. With this chart, St. Armand extracts what he dubs Dickinson’s “solar myth” or “The Romance of Daisy and Phoebus” from the Master letters and poetry, which he calls

the most powerful inner fact in the evolution of Dickinson’s sensibility.

But perhaps this myth and chart are a bit too “handy” and link correspondences too neatly, preventing us from seeing and hearing the complications not bound by this heterosexual meta-narrative. The important point this theory makes is to link Dickinson’s notion of time with notions of space, geography, psychology and experiences of love and passion (object undisclosed).

In her innovative approach from the perspective of cognitive linguistics, Margaret Freeman takes this line of thinking this even further. She argues, first, that metaphor-making is not unique to poets but is how we all understand the world. Second, that Dickinson rejected the dominant metaphor of her religious background, that “LIFE IS A JOURNEY THROUGH TIME,” replacing it with a metaphor garnered from the latest scientific discoveries of her day, that “LIFE IS A VOYAGE IN SPACE.” Thus, image clusters related to “path” and “cycle” and “Air as Sea” reflect

a physically embodied world and create Dickinson’s conceptual universe.

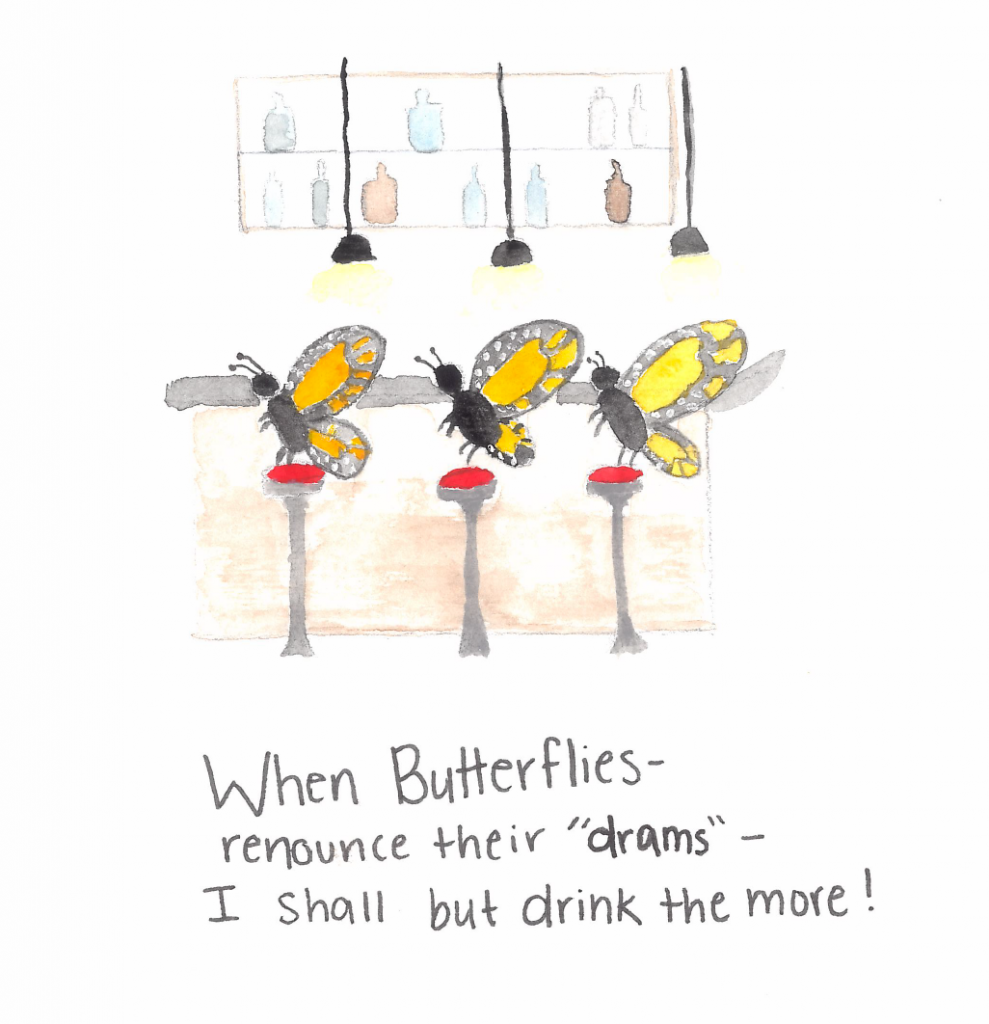

It is, perhaps, this embodied intensity that leads Peggy O’Brien to declare:

There is no poet … who lives more on the edge of every single second than Emily Dickinson: “Each Second is the last” (F927). She seems determined in poem after poem to ground the soaring statement “Forever – is composed of Nows –” (F690) in a single, solid now.

Reflection

Zoë Pollak

As Professor Schweitzer notes, the first posthumously-published volumes of Dickinson divide the poetry into four themes: “Life,” “Love,” “Nature,” and “Time and Eternity.” It’s easy to understand why editors Thomas Higginson and Mabel Loomis Todd took it upon themselves to offer Dickinson’s first readers a framework with which to approach such a vast archive. What’s curious is the logic that led the pair to come up with divisions like “Life” and “Nature” given the extent to which such broad categories overlap. How did they determine whether a poem with a first line like, say, “My life closed twice before it’s close –” (F1773A) would fall under “Life” or get tucked into “Time and Eternity”?

As Professor Schweitzer notes, the first posthumously-published volumes of Dickinson divide the poetry into four themes: “Life,” “Love,” “Nature,” and “Time and Eternity.” It’s easy to understand why editors Thomas Higginson and Mabel Loomis Todd took it upon themselves to offer Dickinson’s first readers a framework with which to approach such a vast archive. What’s curious is the logic that led the pair to come up with divisions like “Life” and “Nature” given the extent to which such broad categories overlap. How did they determine whether a poem with a first line like, say, “My life closed twice before it’s close –” (F1773A) would fall under “Life” or get tucked into “Time and Eternity”?

We’d be hard-pressed to find a speaker in Dickinson who isn’t on some level struggling with how to conceive of time, with how to position him or herself both within and outside of its passage. Given that Dickinson’s thought experiments often contradict each other metaphysically both within and across poems (“Eternity” can be simultaneously “ample” and “quick enough” [F352B], and the same mechanism that “expands” time in one stanza “contracts” it in the next [F833A]), Higginson and Todd’s impulse to yoke time with eternity and restrict them to a single category might seem presumptuous. By cordoning off this category to the end of the volume, the editors supply us with an architecture that’s implicitly exegetical—they physically structure our encounter with “Time” in Dickinson, and curate the way we approach it.

And yet their headings, as capacious as they are reductive, actually manage to preserve and recreate the paradoxes that inhere in many of the poet’s compositions. On one hand, if “Life” leads to “Eternity,” we are faced with the traditional Protestant telos that several of this week’s critics argue Dickinson resists (that is, the Calvinist notion that “‘life is a journey through time,’ which ends at death, a gate to Heaven and immortality or Hell and an eternity of pain”). Yet at the same time (so to speak), Higginson and Todd’s design formally—if not ideologically—pushes against this very framework: how can life be a journey through time if the two literally stand at opposite ends of Poems? Ironically, what allows the editors to sustain this dialectic is their having assimilated “Time and Eternity” into one heading, a merging which would have most likely alarmed John Calvin and Dickinson alike.

I’d imagine that many of us probably find specious the intimation that only some of Dickinson’s poetry is steeped in time. To take this immeasurable medium and compress it into a single region within the span of the poet’s oeuvre demands the bravado of a Marvellian lover. For that matter, it would be a mistake to try and disentangle Dickinson’s treatment of time from her engagement with equally sprawling and diffuse concepts like “space, geography, psychology,” as Professor Schweitzer reminds us. Margaret Freeman suggests that Dickinson

replaced the standard religious teaching about time and eternity with the metaphor of “life is a voyage through space,” non-linear imagery [Dickinson] gleaned from her readings in the new sciences that “saw space as a vast sea, with the planets as boats, circling in sweeps around the sun.”

Despite this renegade move, Dickinson is clearly in conversation with the writers and thinkers around her when she confirms time and space as inseparable. We don’t require the parlance of contemporary physics to recognize that these dimensions exist on a continuum; we need only refer to a sonnet of Shakespeare or song of Donne to realize that it’s impossible to fathom—let alone portray—one medium without enlisting the aid of the other. (How, for instance, can we picture an object moving in space other than through a period of time, and how can we imagine time’s trajectory without conjuring a path in space?)

As Peggy O’Brien puts it, Dickinson “makes [time] palpable and pressing” to allow herself and her readers “to inhabit this metaphysical plane”:

Time feels so vast that were it not

For an Eternity –

I fear me this Circumference

Engross my Finity – (F858A)

So marvels one of Dickinson’s speakers, transmuting what would otherwise be abstract geometrical proportions into ripples, so that even as circle swallows circle, none of the water disappears. The concept of time as a stream is easily as old as Heraclitus, and made memorable by contemporaries of Dickinson’s like Thoreau. What Dickinson does differently is to thicken time into a substance not in order to crystalize it into something hard like a bead of amber or her hermetically palindromic “noon,” but rather to seize upon time as motion, to vivify time’s presence by emphasizing its evanescence. Summer may lapse away “As imperceptibly as Grief” (F935B), but that lapse leaves “A Quietness distilled.” And while in one poem “too happy Time dissolves / itself / And leaves no remnant by – ” (F1182A), in another we get closer to grasping “Forever” when we let “months dissolve in further / Months” (F690A).

Dissolves and distillations: there’s something about conceiving of time as a substance changing states that makes it feel tangible. I doubt we’d be half as receptive to sunsets if we could count on the sky’s amethysts and golds not to metamorphose into some other color each time we looked away; alterations are what sharpen our senses enough to detect them in the first place. After all, alchemists, those other masters of dissolving and distilling, gave their days to meting and measuring out transformations precisely to secure the eternal.

bio: Zoë Pollak is a Ph.D. candidate at Columbia University working in 19th-century American literature and is particularly interested in writers who alternate between poetic and essayistic forms. She graduated with a B.A. in English from the University of California, Berkeley in 2014, and received an M.St. in English from the University of Oxford in 2016, where she focused on early 20th-century American poetry.

Sources

Overview

Cameron, Sharon. Lyric Time: Dickinson and the Limits of Genre. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1979, 23.

O’Brien, Peggy. “Telling the Time with Emily Dickinson.” Massachusetts Review 55. 3 September 2014:468-79, 470.

History

Harper's Monthly, November 1862

Hampshire Gazette, December 2, 1862

Springfield Republican, November 29, 1862

Biography

Freeman, Margaret. “Metaphor Making Meaning: Dickinson’s Conceptual Universe.” Journal of Pragmatics 24 (1995): 643-666, 643.

O’Brien, Peggy. “Telling the Time with Emily Dickinson.” Massachusetts Review 55. 3 September 2014:468-79, 469.

Poulet, Georges. Studies in Human Time. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1970, 346.

St. Armand, Barton Levi. Emily Dickinson and Her Culture: The Soul’s Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984, 81-82, 277-78, 317.