This week in 1862 several items appeared in the newspapers and periodicals on the theme of suffering and sacrifice. Not surprising subjects during wartime, they frame our exploration of a cluster of poems from this period in Dickinson’s life that use imagery of the Crucifixion to explore suffering and sacrifice.

This week, the Springfield Republican published a poem titled “The Sweetest Death” that extols the glory of giving one’s life for one’s “fatherland” and the entanglement of sacrifice and love. This was a common refrain in poetry and prose of this era, which justified the bloody battles of the Civil War as a necessary “purging” of the national sin of slavery.

Right on cue, Ralph Waldo Emerson published an encomium on President Lincoln’s “Emancipation Proclamation” in the November issue of the Atlantic Monthly. In his praise of the president, Emerson specifically remarks:

This act makes that the lives of our heroes have not been sacrificed in vain.

Suggesting that without a momentous paradigm-shift in national consciousness and national policy, the deaths of so many soldiers and civilians might, indeed, have been sacrificed for nothing.

Readers often regard Dickinson’s allusions to the Crucifixion as more of an exploration of personal and psychic suffering than part of a religious or devotional tradition. Clustering in the months after she experienced her great “Terror,” poems with this imagery resonate both personally and religiously, and as so much in Dickinson’s writing during this period, take on an extra valence of meaning in the light of the war’s onslaught of suffering and loss.

“Life in America had Lost Much of its Attraction”

Springfield Republican, November 15, 1862

Progress of the War, page 1

“The event of the week has been the removal of Gen. McClellan from the command of the army in Virginia, and the substitution of Gen. Burnside in his place. The special reasons for the act are not known, but a letter of Gen. Halleck to Secretary Stanton, indiscreetly given to the newspapers, reveals the fact that Gen. McClellan delayed to move into Virginia for nearly three weeks after he had received positive orders to do so, and Gen. Halleck insists that the excuse that the army was not properly supplied with clothing is insufficient. Doubtless the president had other reasons, which will be made public at a suitable time, and which will show that the pledge given to McClellan, when he was implored to resume the command and protect Washington and drive back the rebel invaders, for the campaign should not be interfered with, has not been violated in spirit if it was in letter.”

The Southern Church and Slavery, page 4

“The Richmond Christian Advocate proposes a convention of the Christian churches of all denominations at the South to unite in a formal solemn testimony in vindication of their position in the sanguinary conflict which the federal conflict is waging against them. It wants such a testimony to demonstrate to their enemies and to the world that the southern churches are a unit in their unalterable resolution to maintain the independence of the confederacy, and defend their conservative and scriptural principles on the slavery question.”

Original Poetry, page 6 "The Sweetest Death"

[described in The Northern Monthly: A Magazine of Original Literature and Military Affairs, vol. 1. Ed. Edward P. Weston. Portland: Bailey and Noyes, 1864, 249 as “From the German of Wolfgang Mühler.”]

Hampshire Gazette, November 18, 1862

True Felicity, page 1

“If men did not know what felicity dwells in the cottage of a virtuous poor man—how sound he sleeps, how quiet his breast, how composed his mind, how free from care, how easy his provision, how healthy his morning, how sober his night, how moist his mouth, how joyful his heart—they would never admire the noises, the diseases, the throng of passions, and the violence of unnatural appetites, that fit the houses of the luxurious and the hearts of the ambitious.”

Atlantic Monthly, November 1862

“The President’s [Emancipation] Proclamation,” by Ralph Waldo Emerson

"Better is virtue in the sovereign than plenty in the season," say the Chinese. 'T is wonderful what power is, and how ill it is used, and how its ill use makes life mean, and the sunshine dark. Life in America had lost much of its attraction in the later years. The virtues of a good magistrate undo a world of mischief, and, because Nature works with rectitude, seem vastly more potent than the acts of bad governors, which are ever tempered by the good-nature in the people, and the incessant resistance which fraud and violence encounter. The acts of good governors work at a geometrical ratio, as one midsummer day seems to repair the damage of a year of war. …

This act makes that the lives of our heroes have not been sacrificed in vain. It makes a victory of our defeats. Our hurts are healed; the health of the nation is repaired. With a victory like this, we can stand many disasters. It does not promise the redemption of the black race: that lies not with us: but it relieves it of our opposition. The President by this act has paroled all the slaves in America; they will no more fight against us; and it relieves our race once for all of its crime and false position. The first condition of success is secured in putting ourselves right. We have recovered ourselves from our false position, and planted ourselves on a law of Nature.

“The Man of Sorrow”

Though Dickinson came of age at a time when scientific thinking seriously challenged earlier religious foundations, she was, as Shira Wolosky argues, saturated in the Calvinist beliefs of her ancestors and family members. They embraced a

biblical and providential vision, encoding events in nature, history, and the self in an overarching divine pattern. … This divine order was specifically revealed through biblical pattern, focused on the life of Christ.

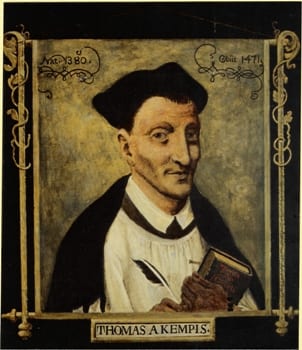

The devotional practice Christians called “the imitation of Christ” has a long tradition. A fifteenth-century German monk named Thomas à Kempis (1380-1471) wrote a meditation on the spiritual life called Imitatio Christi, in which he urged readers to imitate Jesus and live a life of love and service. The Dickinson library contained two editions in English translation; it was apparently a favorite of Dickinson’s.

The devotional practice Christians called “the imitation of Christ” has a long tradition. A fifteenth-century German monk named Thomas à Kempis (1380-1471) wrote a meditation on the spiritual life called Imitatio Christi, in which he urged readers to imitate Jesus and live a life of love and service. The Dickinson library contained two editions in English translation; it was apparently a favorite of Dickinson’s.

Dickinson wrote so many poems about the life of Jesus Christ all through her career that Dorothy Oberhaus argues they “form something like a nineteenth-century American Gospel.” By doing so, Oberhaus believes that Dickinson “stresses the Gospels’ contemporary relevance,” and furthermore, the

deep structure of her Gospel poems places them in the poetic tradition of Christian devotion, a tradition extending from the “Dream of the Rood” and Pearl poets, through the medieval lyricists, Herbert, Vaughan, Crashaw, and Hopkins, to Eliot and Auden in our own day.

Rather than highlight the Resurrection and promise of salvation, as many of these religious writers did, however, Dickinson fastened on the image of the suffering and abandoned Jesus of the Crucifixion, a man experiencing human death. The question why a beneficent and omnipotent God allows human suffering resonated powerfully with the public events and discussions of the day.

References to Jesus of the Cross appear in Dickinson early letters, as in this description from May 7 and 17, 1850 sent to her friend Abiah Root about the death of another friend’s father:

What a beautiful mourner is her sister, looking so crushed, and heart-broken, yet never complaining, or murmuring, and waiting herself so patiently! She reminds me of suffering Christ, bowed down with her weight of agony, yet smiling at terrible will. “Where the weary are at rest” these mourners all make me think of – in the sweet still grave. When shall it call us? (L36)

The quotation Dickinson offers echoes the Book of Job, considered a precursor of Jesus’s passion story, in which the afflicted man curses the day of his birth and calls for death, for “there the weary be at rest” (3:17). And while in this passage Dickinson strikes a naïve and romanticized note, Linda Freeman observes

that she was beginning, even at nineteen, to comprehend the philosophical meaning of the cross and her imagination was struck by the idea that Calvary was a test of Christ’s humanity–his patience, his agony, his suffering and his subservience to the divine will of the father.

Still, this letter is a far cry from the despairing pain of Dickinson’s later poetic invocations of Calvary, the hill on which Jesus was crucified, as we will see in the poetry section. Patrick Keane notes that in her “orthodox moods,” Dickinson depicts Jesus conventionally, as “the divine Son of Jehovah” but “her Jesus is far more often the human Sufferer admired by Schopenhauer and Nietzsche,” modern philosophers who rejected religious systems of belief but admired Jesus. In a letter written late in her life, Dickinson explained this focus to Mrs. Henry Hills:

When Jesus tells us about his Father, we distrust him. When he shows us his Home, we turn away, but when he confides to us that he is “acquainted with Grief,” we listen, for that also is an Acquaintance of our own. (L932)

But, as Keane notes, Dickinson understands Jesus’s humanity even more radically, and this was the source of its powerful hold on her imagination. Writing to Thomas Wentworth Higginson in 1877, she said:

To be human is more than to be divine, for when Christ was divine, he was uncontented till he had been human.(L519)

Keane offers as evidence a poem dated 1882, in which Dickinson seems to say that even the Resurrection was “testimony to the humanity of Jesus:”

Obtaining but

our own extent

In whatsoever

Realm –

'Twas Christ's

own personal

Expanse

That bore him

from the Tomb – (F1573, J1543)

Dickinson’s adaptation of a part of the ancient devotional practice called “imitatio Christi” (imitation of Christ) allowed her to explore the nature of God, the realm of suffering and renunciation, the limits of “fallen” human language, and the burden of the body and the natural world.

Reflection

Sheila Byers

Calvary offers an opportunity to think about the complicated relationships between speaker and setting and internal and external that occur in Dickinson’s poems. Calvary is a place, a location in which a person can stand surrounded by a specific environment. It is also a site, a location known not as the physical place in the world that its name indicates, but as the setting in which the crucifixion occurred.

Calvary offers an opportunity to think about the complicated relationships between speaker and setting and internal and external that occur in Dickinson’s poems. Calvary is a place, a location in which a person can stand surrounded by a specific environment. It is also a site, a location known not as the physical place in the world that its name indicates, but as the setting in which the crucifixion occurred.

When Dickinson talks about the crucifixion, she is interested not only in the event with its spiritual or personal meanings, but also in the place that is the container to that event, its physical and geographical surroundings. But if the word Calvary means a hill outside Jerusalem, it also means “skull,” the name deriving from either the shape of the hill or the objects found there. Calvary is both a place external to the person who stands in it and the bones internal to that person. It is container and contained.

For Dickinson, of course, it is also a metaphor. It is agony, woe, the suffering of Christ. Here the troubling of internal and external intensifies. In “I measure every grief I meet,” Calvary is something the speaker passes, something external that also refers to the internal feeling of grief. When the speaker passes, she feels “A piercing Comfort.” She is pierced, meaning something passes from outside to inside. With this action, Calvary, the external symbol of the speaker’s internal grief, crosses the line of division between speaker and environment, reentering the space of the internal. In this action, grief becomes comfort.

These dizzying reversals of internal and external lead back to the question discussed in this week’s post: In what sense does Dickinson internalize the meaning of the Crucifixion? Is Calvary a projection of the speaker’s grief onto Biblical structures? Or an attempt to draw the stories of scripture into a personalized space of understanding? Or is it, perhaps, both, simultaneously a hill and a skull?

Bio: Sheila Byers is a PhD student in the English Department at Columbia. She works on 19th century American literature with a focus on the intersections of literature, science, and philosophy.

Jennifer Leader

Why, then, do you fear to take up the cross when through it you can win a kingdom? In the cross is salvation, in the cross is life, in the cross is protection from enemies, in the cross is infusion of heavenly sweetness, in the cross is strength of mind, in the cross is joy of spirit, in the cross is highest virtue, in the cross is perfect holiness. There is no salvation of soul nor hope of everlasting life but in the cross.

— Thomas à Kempis, Imitation of Christ

When we suffer—and suffer inconsolably—we desperately wish for something larger and redeeming to come from our losses, if not for ourselves, then for the sake of others. If some meaning and gain can be made of and from our pain, we reason, then perhaps, as Dickinson writes in one of her most anthologized poems, we “shall not live in vain” (F982, J919). And, while I don’t believe the majority of Dickinson’s crucifixion poems to be a conscious attempt on her part to participate in a tradition of Christian devotional works, perhaps her desire to find a redemptive purpose behind the tremendous suffering inherent to the human condition is why she borrowed this image so frequently.

Like most of the more than two hundred references to the Bible in her poetry, Dickinson’s poems featuring or at least pointing toward the crucifixion are at play on many levels at once—on the level of national and personal losses of the Civil War, as a shorthand for individual grief, psychic or romantic pain, and, occasionally, as purely or mostly spiritual trope. Chief among the uses Dickinson makes of the cross is as an image of renunciation, what she terms “a piercing Virtue,” “the Choosing / Against itself – / Itself to justify / Unto itself -” (F782, J745).

Sometimes this renunciation is connected to thwarted romantic love, as in the beautiful “There came a Day at Summer’s full” in which the lovers share a day of communion so pure that it rivals “Sacrament” and the future “Supper of the Lamb,” a consummation depicted in the Bible as taking place between God and his “Saints, / Where Resurrections – be -” (F325, J322). The poem’s communion ends with separation, however, and a sense that as “Each bound the Other’s Crucifix -,” their love will not be allowed to be expressed again until after the resurrection, when it will have been “Justified” by this, their self-renunciatory “Calvaries of Love.”

Yet sometimes Dickinson’s lauding of renunciation makes me ask, “renunciation for what purpose?” I find that I agree with Joan Feit Diehl when she links this aspect of Dickinson’s writing to the Romantic movement and to the sense that suffering for its own sake gives an aesthetic and revelatory payoff; in this vein one could lay some of Dickinson’s poems alongside those of her contemporary Christina Rossetti and note more similarities than differences.

For me, this is where Dickinson’s use of the cross differs from the Christian devotional tradition: in the gospels, renunciation is a temporary means to an end, performed in the light of eternity for the sake of intimacy with a Savior, whereas in Dickinson’s poetry it is more frequently an end goal or fixed and final state; it is self-fulfilling rather than pointing away from self; the speaker’s story is not folded into a larger divine narrative as in “Dream of the Rood.” Instead, the lovers’ separations become dramatizations of making a virtue of necessity, and individual existential suffering ends with the speaker crowning herself “The Queen of Calvary -” (F347, J348).

Dickinson seems to find it hard to poetically pair the grief of the cross with the once-and-future joy of the sort found in the Christian Scriptures (e.g. Jesus, “who for the joy that was set before him endured the cross, despising the shame, and is set down at the right hand of the throne of God”) and the Thomas à Kempis passage above (Heb. 12:2, KJV). Rather, Dickinson’s joys are in the natural world and the beloved human relationships she so cherishes. But perhaps this is why as a reader and a critic I have mostly shied away from Dickinson’s crucifixion references—Dickinson knew the cross demands an emotional response; it makes us look at it without turning away to numb ourselves; it makes us take an accounting of rather than deny or despise our own suffering and the suffering of others. These are emotional equations I’d rather not solve. This is the religion of Lydia Maria Child and Harriet Beecher Stowe, putting sentiment and empathy to use to change their world.

Not, mind you, that Dickinson couldn’t write a profoundly—and orthodox—devotional poem when she wanted to. “Jesus! thy Crucifix” (F197, J225) and “One crown that no one seeks” (F1759, J1735) are both cries of the heart in the Other-reverential spirit of what one might have found in her Congregational hymnal. But for me, the most interesting poems in which Dickinson chooses to participate in Christian tradition are the ones in which she makes use of the Protestant hermeneutics of typology, the practice of locating foreshadowings of Christ in the Hebrew Bible that are ultimately fulfilled in the Christian Scriptures.

This practice was extended by Jonathan Edwards into the wider text of the natural world and by Dickinson’s own nineteenth-century into such a broad trope that seminary textbooks cautioned new preachers against making too frequent use of what was becoming a hackneyed metaphor. Yet Dickinson frequently appropriated the structures of typology as a way to connect the material and temporal realm with the eternal and spiritual. In “One crucifixion is recorded – only-” (F670, J553), “Gethsemane” “is but a Province – in the Being’s Centre -,” and though the speaker finds that there are many “newer” and “nearer” crucifixions than that famous one, “Our Lord – indeed – made Compound Witness -.” As discussed earlier in “On Choosing the Poems,” Dickinson’s use of this last phrase is suggestive of interest on a loan (and, indeed, several of the poems in this section rely heavily on language emphasizing and contrasting the price of a life alongside the price of consumer goods).

Yet Dickinson’s term “Witness” is also remarkable. In A Kiss From Thermopylae: Emily Dickinson and Law, James Guthrie notes that Dickinson was frequently called upon by her lawyer father Edward to perform the legal function of signing as a witness to numerous document transactions he performed for clients. For Dickinson, then, the term “Witness” carried a weighty import. On the cross, Christ was serving as a “Witness” to two “Compound” parties in transaction with each other, the Heavenly father and the earthly children (and legal terms are used frequently both by the Apostle Paul in the Christian Scriptures and in the Covenant theology of the Reformed churches); by doubly being crucified and serving as “Witness” of it, he has created and inhabited an interstitial space allowing Heaven and earth to meet. “Gethsemane” is now “a Province – in the Being’s Centre–” that typologically references and is fulfilled in this moment on the Cross.

Indeed, the mirroring and “Compound”-edness of this poem puts me in mind of the “Compound Vision” and “Convex – and Concave Witness” of another typological poem referencing Christ’s death, “The Admirations – and Contempts – of time-” (F830, J906). Written in 1864, it seems a fitting (and Protestant) end of this meditation, leading “through an Open Tomb-.”

The Admirations – and Contempts – of time –

Show justest – through an Open Tomb -

The Dying – as it were a Hight

Reorganizes Estimate

And what We saw not

We distinguish clear -

And mostly – see not

What We saw before -’Tis Compound Vision -

Light – enabling Light –

The Finite – furnished

With the Infinite -

Convex – and Concave Witness -

Back – toward Time -

And forward –

Toward the God of Him -

Sources:

Thomas à Kempis. Imitation of Christ, ch. 12 par. 77. Christian Classics Ethereal Library

Guthrie, James R. A Kiss From Thermopylae: Emily Dickinson and Law. University of Massachusetts Press, 2015.

bio: Jennifer Leader is Professor of English at Mt. San Antonio College in Walnut, California. She is the author of Knowing, Seeing, Being: Jonathan Edwards, Emily Dickinson, Marianne Moore and the American Typological Tradition (2016). Most recently she has contributed essays on Dickinson, Walt Whitman, and Marianne Moore to The Bible and Feminism: Remapping the Field (2017), Whitman/Dickinson: A Colloquy (2017), and Twenty-First Century Marianne Moore: Essays From a Critical Renaissance (2018).

Sources

History

Atlantic Monthly, November 1862

Hampshire Gazette, November 18, 1862

Springfield Republican, November 15, 1862

Biography

Freedman, Linda. Emily Dickinson and the Religious Imagination. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011, 140.

Keane, Patrick J. Emily Dickinson’s Approving God: Divine Design and the Problem of Suffering. Columbia: University of Missouri Press 2008, 92-93.

Oberhaus, Dorothy. “‘Tender Pioneer’: Emily Dickinson's Poems on the Life of Christ.” American Literature 59.3 October 1987: 341-58, 341.

Wolosky, Shira. “Public and Private in Dickinson’s War Poetry.” A Historical Guide to Emily Dickinson. Ed. Vivian Pollak. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004. 103-131, 114,

Yin, Joanna. “The Imitation of Christ.” An Emily Dickinson Encyclopedia. Ed. Jane Donahue Eberwein. Westport, CT.: Greenwood Press, 1998, 158-59.