It still seems important to recognize and celebrate the boldness and courage of Emily Dickinson in the face of persistent mythologies that reduce her to the status of a quaint, reclusive, heart-broken spinster. And so, in some of our first posts, we examined Dickinson’s explorations of themes of agency and power, like entitlement and choosing. This week, however, following on several posts on Dickinson’s garden politics, we explore her engagement with Eastern thought, especially the ancient Chinese philosophy of Daoism and Chan (also spelled Ch’an or Zen) Buddhism which developed from it, and the aesthetics that flow from these schools of thought.

Coincidentally, May is Asian-American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month (AAPIHM) in the United States, so this theme seems even more appropriate. The influence of an “Eastern spirit” on Dickinson produces a different, though not, we would argue (in the feminist spirit of both/and), incompatible kind of ontology, which to Western eyes can look like “blandness,” the opposite of boldness.

Scholars have begun to investigate Dickinson’s involvement with Eastern thought and how she learned about it. In the Biography section, we will detail several trips she made to Boston in the 1840s and 1850s, a town with a long history of trade with China, There, she visited the newly opened Chinese Museum and even met a recovering opium eater! As Cristanne Miller shows and we discussed several weeks ago, New Englanders were fascinated with the Orient and things eastern, which began in the 1840s as translations of Buddhist texts in English appeared, and peaked in the 1850-60s. Several of the magazines that the Dickinson family read regularly carried stories about the East and introductions to Buddhist thought.

Another possible source of influence was the homegrown Transcendental writers, Emerson and Thoreau, who read Eastern works, like the Bhagavad Gita, and borrowed and adapted some of their core ideas about the centrality of contemplation, stillness, receptiveness, nature as a model, self-denial, detachment, and non-possession.

However Dickinson absorbed the ideas of Eastern philosophy, she applied them to her poetic explorations about selfhood, nature, theories of language and representation, and formal, aesthetic choices. It is easy to see how her short poems and habitual compression resemble the Japanese poetic form of haiku. But it is more startling to realize that we can understand her many poems about renunciation, for example, not only in terms of romantic heartbreak but as a stage in the Buddhist journey towards “liberation.” A summary of Eastern thought, which Dickinson might have read, called this state “annihilation:”

that all things originated in nothing, and will revert to nothing again. Hence annihilation is the summit of bliss; and nirupan, nirvana, or nonentity, the grand and ultimate anticipation of all.

We can only imagine how thrilled Dickinson would have been to find a philosophy and practice that could deliver her from the world of illusion!

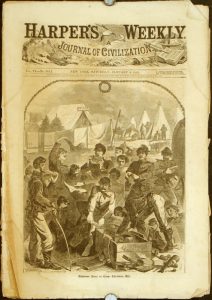

“The grand struggle of the war has not yet come off.”

NATIONAL HISTORY

Springfield Republican May 24, 1862, page 1

Review of the Week: “Progress of the War.”

The march to Richmond has been found more difficult than it had been popularly estimated. Continued rains have made the usually bad road almost impassable, and as our army nears the confederate capital it enters the region of miserable swamps with which the city is environed, and through which a great deal of road has to be actually built. … The rebels thus seem to have the ability to concentrate at Richmond all their forces in Virginia, and to meet Gen McClellan with superior numbers. Notwithstanding this, the known demoralization of a large portion of the rebel army, and the assured caution and skill of our commanders, give great confidence of success in the approaching contest.

“The General Situation:”

The special agitation of the week has grown out of an order by Gen Hunter, of the department of the South, declaring all the slaves free in his department—South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida. The only reason stated by him for this order was that slavery is inconsistent with martial law in order to prevent certain government agents from abusing the negroes. … It was manifest, however, to all sane men that the president could do no otherwise than recall and annul Gen Hunter’s order, which he did in a proclamation, in which he stated that he reserves to himself as commander-in-chief, the decision of the question whether he shall resort to this measure, and when and how.

New England Affairs: “A warm term, a cool morning and showers of rain have diversified the weather and considerably benefited vegetation in general. The country looks as beautiful as the most blooming bride.”

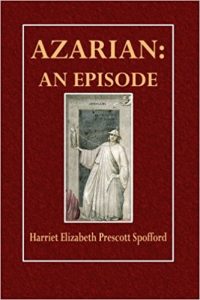

FROM BOSTON. From Our Own Correspondent. “The publishers of the Atlantic give their readers twelve extra pages of reading matter in the June number; so they may be pardoned for printing Mr. F. G. Tuckerman’s sonnet, which is probably the worst sonnet ever written, and liable to be printed among the curiosities of literature as such. I have read the conclusion of “The South Breaker” [by Harriet Spofford], which is very fine. “Walking” by Henry Thoreau, is natural and breezy … There is no risk in praising Mr Higginson’s essay, “The Health of our Girls.” There is a piece by Whittier, commemorative of the abolition of slavery at the national capital; a fine poem by Alice Carey, entitled “An order for a picture,”one by Rose Terry,—whose stories are so good—and Mr Lowell’s Biglow paper, entitled “Sumthin’ in the Pastoral Line,” which is far better than anything he has given us before, in the present series. … the conclusion, being the sound and salutary advice communicated to Hosea [the speaker of the poem] by the old Pilgrim father, who came to him in a dream …” Signed Warrington.

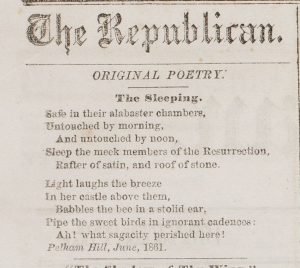

Original Poetry, page 6

“The Burial at Sea,” in the ballad measure by F. H. C.

“The Conflict of Ages” by B. Hathaway in 6 line stanzas of iambic tetrameter rhyming abbaab. [We found this title in The Rebellion Record: A Diary of American Events, Volume 4].

“The Old Story” by Chauncey Hickox (1837-1905) in iambic tetrameter couplets. [Hickox, originally from Ohio but married in Connecticut, enlisted with the Union forces in October 1862.]

Tribute to a Massachusetts Woman.— Mrs. Dall, in her admirable book entitled “Historical Pictures Retouched,” pays tribe to the patience and thoroughness of a lady astronomer” Maria Mitchell: “Women are also more patient, thorough, and observant of small facts than man. …”

Genius and Labor. This short piece mentions three people, all male: Alexander Hamilton, Mr. Webster and Demosthenes.

“Daisies” reprinted from the Boston Transcript

Hampshire Gazette May 27, 1862, page 1

Hampshire Gazette May 27, 1862, page 1

Leads off with three poems:

Written for the Gazette and Courier, “Prayer for the Union,” Tune—Old Hundred, and signed Newbern, N.C. April. E. W. F.

“New England’s Dead” by Isaac McLellan:

On every hill they lie;

On every field of strife, made red

By bloody victory.

Written for the Gazette and Courier, “Passing Away” by E. A. W. also about the war dead, and written from “Hospital, Northampton, May, 1862.

“Facts about Manure.”

Farmers are beginning to appreciate the value of manure. Only a few years since, it was difficult for keepers of horses in this and other cities to sell a load of manure, or even get it drawn from their stables without charge. … but now … it is with the greatest difficulty we can obtain enough in the spring to make hotbeds, while for other purposes we are compelled to resort to guano.

Page 2 Notes of the Week: “The grand struggle of the war has not yet come off.”

How Massachusetts Responds. “Great Enthusiasm.” A dispatch from Boston says the call upon the volunteer militia of Massachusetts for active service is being gloriously responded to. The enthusiasm of April, 1861, is renewed.”

“Slavery, as viewed by Great Southern Statesmen.”

Jefferson— “I tremble for my country, when I reflect, that God is just.” In his Ordinance of 1787, approved by Congress unanimously, it was declared there should be no “slavery” in the United States after the year 1800.

Washington—“There is no man living, who wishes more sincerely, than I do, to see a plan adopted for the abolition of slavery.”

Madison—“This evil has preyed upon the very vitals of the Union”

Randolph—“I envy neither the heart no the head of that man from the North, who rise here to defend slavery on principle.”

Clay—“Never will I aid in admitting one rood of free Territory to the everlasting curse of human bondage.”

“The Chinese Museum”

According to Hiroko Uno, when Dickinson was fifteen, she visited the Chinese Museum in Boston in Fall 1846, while staying with her beloved Norcross cousins. The museum opened in 1844, after the signing of the Wanghsia Treaty, the first official trading agreement between the US and China, negotiated and signed by Caleb Cushing, the US congressman from Massachusetts, who was an acquaintance, if not friend, of Edward Dickinson, then a State Senator.

Based on the museum’s catalogue, Uno describes in some detail what Dickinson would have seen there, and we also have Dickinson’s own account of this trip from a letter she wrote to her good friend Abiah Root dated September 8, 1846:

The Chinese Museum is a great curiosity. There are an endless variety of Wax figures made to resemble the Chinese & dressed in their costume. Also articles of chinese manufacture of an innumerable variety deck the rooms. Two of the Chinese go with this exhibition. One of them is a Professor of music in China & the other is teacher of a writing school at home. They were both wealthy & not obliged to labor but they were also Opium Eaters & fearing to continue the practice lest it destroyed their lives yet unable to break the "rigid chain of habit" in their own land They left their family's & came to this country. They have now entirely overcome the practice. There is something peculiarly interesting to me in their self denial (L13).

A bit later in the letter, Dickinson brings up the question of Christian conversion, which, she says somewhat tartly, that Root has “so frequently & so affectionately called my attention [to] in your letters.” Dickinson will face and insistently resist increasingly intrusive pressure to convert when she enters Mount Holyoke Seminar the following year and comes within the purview of its redoubtable headmistress, Mary Lyons. To Root, Dickinson responds:

But I feel that I have not yet made my peace with God. I am still a s[tran]ger – to the delightful emotions which fill your heart. I have perfect confidence in God & his promises & yet I know not why, I feel that the world holds a predominant place in my affections. I do not feel that I could give up all for Christ, were I called to die.

This letter reveals Dickinson’s early exposure to Chinese culture and religion, which had a lasting effect on her thinking and her poetry. Uno asserts that for Dickinson:

Those experiences in the Chinese Museum were so impressive that images of the East resonated for decades in her adult imagination [and were also] deeply connected with her own religious conflicts of faith, especially her difficulty accepting Christ.

The letter reveals her fascination with a central tenet of Buddhism—self-denial—as well as her unwillingness to give up the world in a Christian evangelical sense, and to find her ultimate “reward” in the afterlife. Exploring poems on these themes will allow us to see how Dickinson managed these seemingly competing feelings in 1862, a time in her life when her struggles with conversion (though not belief) were settled, she had accepted a deep form of renunciation, and was in the midst of an immense period of poetic productivity.

Reflection

Chin Woon Ping

Recluse

Recluse

She wears white, the color of Death.

Tight-laced, hair pulled back,

Her Mind roams all realms.

The rhythm a regular hymn—

The form a joy to punctuate—

With dashes.

Success is never counted

By one who practices

Non-attachment.

CWP

bio: Chin Woon Ping has published books of poetry, essays, translations and plays. She has performed her work in the US, Canada, Australia, Japan, China and Southeast Asia and recorded her songs with Scratch and Bite Records. She teaches at Dartmouth College and lives in Vermont.

Sources:

Overview

Uno, Hiroko. “Emily Dickinson’s Encounter with the East: Chinese Museum in Boston.” The Emily Dickinson Journal, 17, 1 (2008): 43-67, 52.

Takeda, Masako. “Emily Dickinson and Japanese Aesthetics.” The Emily Dickinson Journal, 22, 2 (2013): 26-45.

Kang, Yanbin. “Dickinson’s Allusions to Thoreau’s East.” ANQ: A Quarterly Journal of Short Articles, Notes and Reviews. 29:2, 92-97.

—–. “Dickinson’s ‘Power to die’ from a Transcultural Perspective.” The Emily Dickinson Journal, 22, 2 (2013) 65-85.

History

Hampshire Gazette, May 27, 1862

Springfield Republican, May 24, 1862

Biography

Uno, Hiroko. “Emily Dickinson’s Encounter with the East: Chinese Museum in Boston.” The Emily Dickinson Journal, 17, 1 (2008): 43-67, 61-62.

Still, Cristanne Miller argues that the “being edited” argument—though clearly a concern for Dickinson—is insufficient to explain why so much of her poetry went unpublished. Miller points to two compelling reasons that go beyond Dickinson’s preoccupation with editorial interference. First, her most profound poems deal with matters of life, death, and loss in

Still, Cristanne Miller argues that the “being edited” argument—though clearly a concern for Dickinson—is insufficient to explain why so much of her poetry went unpublished. Miller points to two compelling reasons that go beyond Dickinson’s preoccupation with editorial interference. First, her most profound poems deal with matters of life, death, and loss in