Paradise!

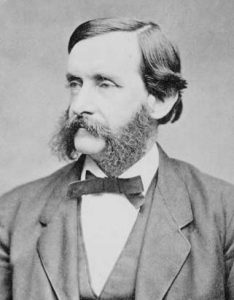

This week in 1862, Emily Dickinson celebrated her 32nd birthday, and there was something to celebrate. She had weathered the emotional crises of the past year, was writing astonishing poetry at an astonishing rate, and had established fruitful relations with a new literary interlocutor, Thomas Wentworth Higginson.

At the end of his “Letter to a Young Contributor,” which a struggling Dickinson read in the April issue of the Atlantic Monthly, Higginson calls on “the mute inglorious Miltons of this sphere” to “sing their Paradise as Found.” At some point in the year, Dickinson will write a signature poem of optimism, “I dwell in Possibility” (F466, J657), that seems to answer Higginson's call directly. Describing her imaginative “dwelling,” and with a characteristic playfulness of scale, she declares:

For Occupation—This—

The spreading wide my narrow Hands

To gather Paradise—

This week, we focus on Dickinson’s stated “occupation,” gathering Paradise. What does she mean by that and what is its relationship to poetry? Next week, on December 19, Susan Gilbert Dickinson would also celebrate her 32nd birthday. Although relations between the two girlhood friends were strained at this time, Dickinson frequently links Sue’s love and support and her boundless love for Sue with “forever” and “Infinity,” a kind of Paradise on earth (see Letters 288 and 912).

But Dickinson was not always so optimistic; she knew Milton’s great poem, Paradise Lost, very well. We also remember the devastating effects of the Camp Fire, which roared through the town of Paradise in northern California in 2018, destroying it. Our literal “Paradise” turned into a hell and burned to cinders by climate change.

But Dickinson was not always so optimistic; she knew Milton’s great poem, Paradise Lost, very well. We also remember the devastating effects of the Camp Fire, which roared through the town of Paradise in northern California in 2018, destroying it. Our literal “Paradise” turned into a hell and burned to cinders by climate change.

Similarly, in gathering Paradise, Dickinson often also failed to find it or lost it, and that is part of this story as well.

“Lift the Earth to Paradise”

Springfield Republican, December 13, 1862

Progress of the War, page 1

“The sameness of long continued planning and preparation is at length relieved by a real battle and several important forward movements. The enemy in northwestern Arkansas rallied from their defeat by Gen. Blunt at Cane Hill [on November 28], and reinforced by Gen. Hindman attacked Gen. Herron’s division of our army at Fayetteville with superior numbers but were repulsed and driven again to the Boston mountains after a battle of great severity. The contest has begun at Fredericksburg, and Gen. Banks’ expedition is moving off in installments to its unknown destinations; important movements of some sort are going forward at Newbern and at Suffolk; the armies of Grant and Hovey have reached Grenada, Mississippi, the enemy retreating before them; a naval expedition has left Hilton Head, S.C., for some point North, and may cooperate with Gen Banks at Wilmington, N.C.; the Gulf squadron has been reinforced for an attack on Mobile; the blockade of Charleston has been strengthened, and all things look like work.”

The First Condition of Peace, page 2

“Our armies are now at their maximum strength. All that we shall add henceforth will not more than replace the natural waste by sickness, desertion and death. The past history of the war shows that location reduces our armies quite as rapidly as an active campaign and demoralizes them more. If, then, the war is to be brought to a successful issue, the ensuing three months must be months of the most energetic activity. If before spring we have taken Richmond, Charleston and Savannah, have driven the rebels from Tennessee, and got full possession of the Mississippi, then we may begin to talk about peace upon terms that shall be honorable to the government and safe for the nation.”

Fallen Leaves (by Henry D. Thoreau), page 7 [excerpted from “Autumnal Hints” in the Atlantic Monthly, October 1862.]

“When the leaves fall, the whole earth is a cemetery pleasant to walk in. I love to wander and muse over them in their graves. Here are no lying nor vain epitaphs. Your lot is surely cast somewhere in this vast cemetery, which has been consecrated as of old. You need attend no auction to secure a place. There is room enough here. The loose-strife shall bloom, and the huckleberry-bird sing over your bones. The woodman and hunter shall be your sextons, and the children shall tread upon the borders as much as they will. Let us walk in the cemetery of the leaves—this is your true Greenwood cemetery.”

Books, Authors and Arts, page 7

“The literary metropolis of New England leans rather to books than periodicals, rather to journals than magazines. The Atlantic Monthly is an exception. Its contributors are many and eminent, not those merely who lend it the luster of their names, but those who write for it often and well. Holmes and Lowell, Emerson and Agassiz have each departments in which they have been rarely equaled, never surpassed. Mrs. Stowe writes as a woman never wrote before, and other feminine authors, a round dozen in number, have furnished essays, romances and poems that could not well be spared. Yet we have a few things against it, deserving and prosperous as it has improved. It has contained during the last year many articles of public interest, yet its statesmanship lacks the impress of a mastermind, and is only to be inferred from the aggregate of varying contributions. Its poetry was very early stigmatized as pretentious and dull, and has varied widely from the average standard, alternating from the vigorous to the vapid.”

Hampshire Gazette, December 16, 1862

“This forever looking forward for enjoyment, don’t pay. From what we know of it, we would as soon chase butterflies for a living, or bottle up moonshine for cloudy nights. The only true course is to take the drops of Happiness as God gives them to us, every day of our lives. The boy must learn to be happy when he is plodding over his lessons; the apprentice when he is learning his trade; the merchant while he is making his fortune. If he fails to learn this art, he will be sure to miss his enjoyment, when he gains what he sighs for.”

Atlantic Monthly, December 1862

[The issue leads off with this essay, a description of paradise on earth]

“The Procession of the Flowers,” by Thomas Wentworth Higginson

“To a watcher from the sky, the march of the flowers of any zone would seem as beautiful as that West-Indian pageant. These frail creatures, rooted where they stand, a part of the ‘still life’ of Nature, yet share her ceaseless motion. In the most sultry silence of summer noons, the vital current is coursing with desperate speed through the innumerable veins of every leaflet; and the apparent stillness, like the sleeping of a child’s top, is in truth the very ecstasy of perfected motion.”

[And the issue ends with this essay, a depiction of hell on earth]

“My Hunt after The Captain” by Oliver Wendel Holmes [Holmes describes his frantic search through Civil War-torn landscapes for his wounded son, the future Supreme Court Justice.]

“And now, as we emerged from Frederick, we struck at once upon the trail from the great battle-field. The road was filled with straggling and wounded soldiers. All who could travel on foot,— multitudes with slight wounds of the upper limbs, the head, or face,— were told to take up their beds,—a light burden or none at all— and walk. Just as the battle-field sucks everything into its red vortex for the conflict, so does it drive everything off in long, diverging rays after the fierce centripetal forces have met and neutralized each other. For more than a week there had been sharp fighting all along this road. Through the streets of Frederick, through Crampton's Gap, over South Mountain, sweeping at last the hills and the woods that skirt the windings of the Antietam, the long battle had travelled, like one of those tornadoes which tear their path through our fields and villages. The slain of higher condition, “embalmed” and iron-cased, were sliding off on the railways to their far homes; the dead of the rank and file were being gathered up and committed hastily to the earth; the gravely wounded were cared for hard by the scene of conflict, or pushed a little way along to the neighboring villages; while those who could walk were meeting us, as I have said, at every step in the road. It was a pitiable sight, truly pitiable, yet so vast, so far beyond the possibility of relief, that many single sorrows of small dimensions have wrought upon my feelings more than the sight of this great caravan of maimed pilgrims. The companionship of so many seemed to make a joint-stock of their suffering; it was next to impossible to individualize it, and so bring it home, as one can do with a single broken limb or aching wound.”

Harper’s Monthly, December 1862

Love by Mishap, Edward Howard House

“But was it the sunlight that suddenly flashed across those four young faces, or the full tide of hope, and joy, and faith bounding ruddy from their hearts, and, as it glowed and beamed, openly telling the secret of their dearest thoughts in that happy hour? Ah, that happy hour! There is none other like it, to glorify the present, to gild the future, to turn the thorny ways of life to paths of bounteous promise, to lift the earth to paradise.”

“Earth so like to Heaven”

We have little information about how Dickinson would have celebrated her 32nd birthday or Susan’s 32nd birthday the following week on December 19, but such anniversaries are often an occasion to sit back and take stock. As explained in the Overview, sometime during this year, Dickinson wrote a poem in which she declared her “Occupation” to be that of gathering “Paradise,” which, presumably, she discerned all around her, there for the taking. Many of her letters support the notion, garnered from Romantic and Transcendental writers, of a Paradise on earth.

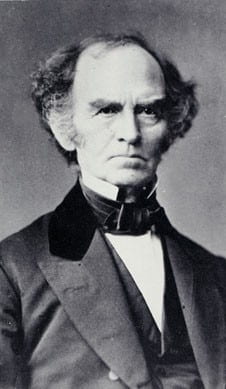

For example, critic Patrick Keane notes that in an 1852 letter to Sue, Dickinson cites but rewrites a passage about an earthly paradise from Milton’s Paradise Lost, a poem she knew well. As the archangel Raphael struggles to explain celestial warfare to a human mind by “lik’ning spiritual to corporeal form,” he wonders:

Though what if Earth

Be but the shadow of Heaven, and things therein

Each to the other like, more than on earth is thought?” (Paradise Lost 5:573-76).

Susan is away at the time of this letter and Dickinson, who is missing her deeply, writes:

I can only thank “the Father” for giving me such as you, I can only pray unceasingly, that he will bless my Loved One, and bring her back to me to “go no more out forever.” “Herein is Love.” But that was Heaven –– this is but Earth, yet Earth so like to heaven that I would hesitate, should the true one call away (L85, 195).

The phrase “go no more out” is from Revelation 3:12 where Christ assures the faithful that on the Day of Judgment, they will never have to leave heaven. Dickinson adds the “forever.” Keane comments on how Dickinson reverses Raphael’s “therein” to locate love “Herein,” on earth “and concludes by taking literally the angel’s rhetorical but intriguing question.” As support, he cites an 1873 letter to Elizabeth Holland, a close friend, in which Dickinson notes that her sister Lavinia just returned from a visit to the Hollands and reported they “dwell in paradise.” Dickinson adds wryly:

I have never believed the latter to be a supernatural site.

Eden, always eligible, is peculiarly so this noon. It would please you to see how intimate the Meadows are with the Sun … While the Clergyman tells Father and Vinnie that “this Corruptible shall put on Incorruption”—it has already done so and they go defrauded (L391, 508).

Paradise, for Dickinson, was closely associated with her friends, her loved ones and gardens, especially at the height of summer, the season for her of ecstasy and transport. Keane borrows the term “Natural Supernaturalism” from the writer Thomas Carlyle to describe Dickinson’s conception of paradise, especially in terms of influences from the works of Romantics like Wordsworth, Keats, and Emerson:

In his essay on the mystic Swendenborg in Representative Men, Emerson claimed that the only thing “certain” about a possible heaven was that it must “tally with what was best in nature.” It “must not be inferior in tone…agreeing with flowers, with tides, and the rising and setting of autumnal stars.”

Dickinson’s “preceptor,” Thomas Higginson, voices a similar view in his essay in the Atlantic Monthly for this month, which Dickinson praises him for in a later letter. In the final passages, he addresses the important point, also on Dickinson’s mind, that our inability to perceive the heaven around us indicates a “defect … in men:”

But, after all, the fascination of summer lies not in any details, however perfect, but in the sense of total wealth which summer gives. Wholly to enjoy this, one must give one's self passively to it, and not expect to reproduce it in words. We strive to picture heaven, when we are barely at the threshold of the inconceivable beauty of earth. Perhaps the truant boy who simply bathes himself in the lake and then basks in the sunshine, dimly conscious of the exquisite loveliness around him, is wiser, because humbler, than is he who with presumptuous phrases tries to utter it. There are multitudes of moments when the atmosphere is so surcharged with luxury that every pore of the body becomes an ample gate for sensation to flow in, and one has simply to sit still and be filled. In after-years the memory of books seems barren or vanishing, compared with the immortal bequest of hours like these. Other sources of illumination seem cisterns only; these are fountains. …

If, in the simple process of writing, one could physically impart to this page the fragrance of this spray of azalea beside me, what a wonder would it seem!—and yet one ought to be able, by the mere use of language, to supply to every reader the total of that white, honeyed, trailing sweetness, which summer insects haunt and the Spirit of the Universe loves. The defect is not in language, but in men. There is no conceivable beauty of blossom so beautiful as words,—none so graceful, none so perfumed. It is possible to dream of combinations of syllables so delicious that all the dawning and decay of summer cannot rival their perfections, nor winter's stainless white and azure match their purity and their charm. To write them, were it possible, would be to take rank with Nature; nor is there any other method, even by music, for human art to reach so high.

But if paradise is a garden, then it has the earthly limits of gardens, such as frost and death. In a letter from August 1856 to Elizabeth Holland, Dickinson describes her vision of heaven on earth with a series of conditional clauses. She also reprises the phrase she used in her 1852 letter to Sue from Revelation 3:12:

I read my Bible sometimes and in it as I read today, I found a verse like this, where friends should “go no more out” … And I am half tempted to take my seat in that Paradise of which the good man writes, and begin forever and ever now, so wondrous does it seem. My only sketch, profile, of Heaven is a large, blue sky, bluer and larger than the biggest I have seen in June, and in it are my friends–all of them–every one of them–those who are with me now, and those who were “parted” as we walked, and “snatched up to Heaven.”

If roses had not faded, and frosts had never come and one had not fallen here and there whom I could not awaken, there were no need of other Heaven than the one below, and if God had been here this summer, and seen the things that I have seen—I guess he would think His Paradise superfluous. Don’t tell Him, for the world, though, for after all He’s said about it, I should like to see what He was building for us, with no hammer, and no stone, and no journeyman either (L185).

From these ideas, Keane concludes,

Emily Dickinson’s Earthly Paradise is not only beautiful but death-haunted.

Reflection

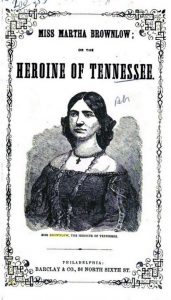

Martha Nell Smith

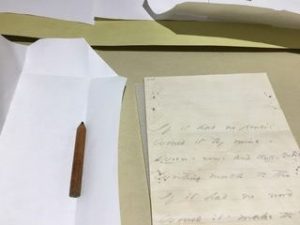

December 1862. Susan and Emily Dickinson have had quite a year. In March, Susan excitedly wrote Emily,

December 1862. Susan and Emily Dickinson have had quite a year. In March, Susan excitedly wrote Emily,

. . .There were two or

three little things I wanted to talk

with you about without witnesses

but to-morrow will do just as

well – Has girl read Republican?

It takes as long to start our

Fleet as the Burnside.

Susan refers to the publication of “The Sleeping,” a version of Emily’s “Safe in their Alabaster Chambers,” just above Susan’s own “The Shadow of Thy Wing.” Their substantive exchange about the meaning, the effects, the power of this poem (see “Emily Dickinson Writing a Poem”) resonate with Susan’s declaration in a letter to Curtis Hidden Page

. . . Poetry is my

sermon – my hope – my solace

my life –

Yours very sincerely

S. H. Dickinsonout of the storm

February seventeenth /

Poetry is Possibility. Gathering wide our narrow hands to gather Paradise. Poetry was sermon – hope – solace – life for both Susan and Emily Dickinson. No wonder the manuscripts passed between them are spattered with traces of wine, delicious morsels, the stains of a flower dried and long pressed against the word made flesh, the pinholes made when attached to Susan’s sewing basket or to an album in which she preserved her beloved friend’s poetry, poetry written and given to her, Emily Dickinson’s most frequently addressed audience. So often and so many were these carnal, heavenly bequests that Susan noted to editor William Hayes Ward how “baffled” Emily’s own sister Lavinia was by Susan’s “possession of so many mss. of Emily’s.”

On May 15, 1886, Emily Dickinson took her last breath, but she left two major archives of her scriptures, verses that are alive and, as long as there are readers, always will be.

1862. A year when Susan contributed “Safe in their Alabaster Chambers” to the Springfield Republican, a year they could savor seeing their work printed together. By the time of their birthdays, Susan had submitted several poems of Emily’s to publications in places such as Drum Beat, Round Table, Brooklyn Daily Union. Back in April, they had strategized which copy of “Safe in their Alabaster Chambers” to send to Thomas Wentworth Higginson in response to his “Letter to a Young Contributor.”

bio: Martha Nell Smith is Distinguished Scholar-Teacher, Professor of English, and Founding Director of the Maryland Institute for Technology in the Humanities (MITH http://www.mith.umd.edu) at the University of Maryland. Her numerous print publications include six singly and coauthored or co-edited books—Emily Dickinson, A User’s Guide (2018); Everywoman Her Own Theology: Essays on the Poetry of Alicia Suskin Ostriker (2018); I Dwell in Possibility: Collaborative Emily Dickinson Translation Project, edited with Professor Baihua Wang, Fudan University (2017); Companion to Emily Dickinson (Jan 2008); Open Me Carefully: Emily Dickinson’s Intimate Letters to Susan Dickinson (1998; Choice); Comic Power in Emily Dickinson (1993; Choice); Rowing in Eden: Rereading Emily Dickinson (1992; Hans Rosenhaupt First Book Award Honorable Mention, Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation)—and scores of articles and essays in journals and collections such as American Literature, Present Tense: Rock & Roll and Culture, Textual Cultures, ESQ, Studies in the Literary Imagination, Journal of Victorian Culture, South Atlantic Quarterly, Women’s Studies Quarterly, Profils Americains, San Jose Studies, The Emily Dickinson Journal, ESQ, Journal of Victorian Culture, and A Companion to Digital Humanities. Most recently, working with Professor Baihua Wang of Fudan University (Shanghai), Smith has edited sections on Dickinson for three different international journals—Comparative Literature, World Literature, Cowrie: A Journal of Comparative Literature and Culture, and the International Journal of Poetry and Poetics. At present she is completing Lives of Susan Dickinson, and Life Before Last: Martha Dickinson Bianchi's Memoir (edited with Jane Wald, Executive Director of the Emily Dickinson Museum).

Sources

Overview

Higginson, Thomas Wentworth. “Letter to a Young Contributor.” Atlantic Monthly, April 1862.

“Camp Fire.” USA Today. November 29, 2018.

History

Atlantic Monthly, December 1862

Harper's Monthly, December 1862

Hampshire Gazette, December 16, 1862

Springfield Republican, December 13, 1862

Biography

Higginson, Thomas. “The Procession of the Flowers.” Atlantic Monthly X. LXII December 1862.

Keane. Patrick. “Natural Supernaturalism: Emily Dickinson’s Variations on the Romantic Theme of an Earthly Paradise.” Numéro Cinq V.12 December 2014.