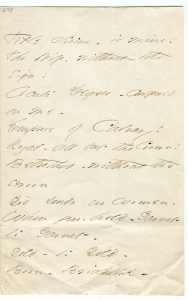

Title divine – is mine!

The Wife – without the

Sign!

Acute Degree – conferred

on me –

Empress of Calvary!

Royal – all but the Crown!

Betrothed – without the

swoon

God sends us Women –

When you – hold – Garnet

to Garnet –

Gold – to Gold –

Gold – to Gold –

Born – Bridalled – ( Shrouded –

In a Day –

“My Husband” – women

say –

Stroking the Melody –

Is this – the way?

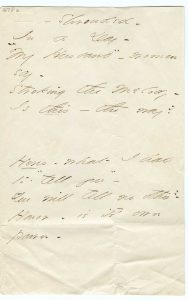

Title divine, is mine.

The Wife without

the Sign –

Acute Degree

conferred on me –

Empress of Calvary –

Royal, all but the

Crown –

Betrothed, without

the Swoon

God gives us Women –

When You hold

Garnet to Garnet –

Gold – to Gold –

Born – Bridalled –

Shrouded –

In a Day –

Tri Victory –

“My Husband” – Women say

Stroking the Melody –

Is this the way –

Link to EDA manuscript. F194A originally in Amherst – Amherst Manuscript # 678 – Emily Dickinson letter to Samuel Bowles – asc:10985 – p. 1. Courtesy of Amherst College, Amherst, Mass. F194B originally sent to Susan Dickinson, 1865 in MS Am 1118.3 (361). Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. First published Life and Letters (1924), 49-50, from the copy to Susan Dickinson (B), in twenty-one lines; also Complete Poems (1924), 176-77, and later collections. Bingham, Emily Dickinson’s Home (1955), 373, from the copy to Bowles (A).

This is a key poem in Dickinson’s canon, and though dated to 1861, she sent it in a letter to Bowles in early 1862 with these brief words:

Here’s – what I had to ‘tell you’– you will tell no other? Honor – is it’s own pawn –(L250).

She would repeat that last phrase as the conclusion to her first letter to Thomas Higginson on April 15 of this year.

Strangely, Dickinson did not copy this poem into a fascicle, but sent a version to Susan Dickinson in 1865, with some key differences worth noting. Sue’s copy (B) leaves out the exclamation points after lines 1, 2, 4 ad 5, the question mark at the end and includes the phrase, “Tri Victory” after “In a Day–”. The version sent to Bowles is altogether more triumphant, even ecstatic, in tone and visual form than Sue’s version, which is more sober.

The poem is often read as a declaration of star-crossed love for one of the men in Dickinson’s life, possibly Bowles, but we offer it as a study in self-entitlement, closely related to the ecstatic declaration discussed in last week’s post, “Mine – by the right of the White Election! (F411A, J528). They are connected by the repetition of the word “mine” and its rhyme, here, with “divine.” Thus, entitlement and whiteness are closely linked by their association with marriage and poetry. Here, though, the marriage is definitely not an earthly one.

The poem brings together an important cluster of images. Titles, often of royalty, that are also, often, self-conferred (like the “unannointed Blaze” of “Dare you see a Soul at the ‘White Heat’” (F 401A, J 365). Dickinson only gave titles to 24 of her poems, and those were poems she sent in letters; only three titles occur in the fascicles. The large majority of her poems go untitled, and yet the conferring of titles is a significant gesture here and in other poems, expressing a recognition of self-worth.

Related images are degree, a word that has 17 meanings in Dickinson’s Webster’s, including “proof of value,” “radius,” “longitude,” “marital status,” “honor,” and “token; symbols; coronation.” In this poem, degree is “acute,” an intensifier that suggests illness, and rhymes boldly with “me.” It also rhymes with the weighty title, “Empress of Calvary,” referring to the hill on which Jesus was executed, which becomes a metaphor Dickinson uses here and in other poems for the agony of suffering and loss. Finally, gems figure preciousness. Here, the double ceremony of holding “Garnet to Garnet–/ Gold –to Gold” formally enacts the tautological comparison of like to like, a radical equality or parity.

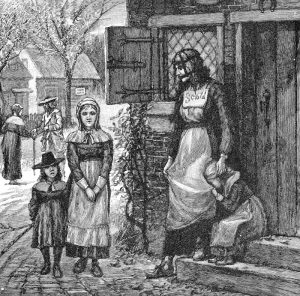

We need to note several voices in the poem expressing different, contradictory attitudes. The first boldly declares her entitlement as a divine wife, without the sign, and criticizes the current institution of marriage, in which women are “Born – Bridalled – Shrouded – /in a Day –”. By making “bridal” a passive verb, Dickinson produces a pun on the word “bridled,” a means of controlling a horse or draught animal through a metal bit in its mouth. This pun evokes the infamous “scold’s bridle,” a Medieval form of punishing unruly, garrulous women, by “branking” them.

Such language, with the implication that women are constrained and even punished by marriage, is echoed in a poem by an earlier New England poet, Lydia Huntley Sigourney. Styled “the Nightingale of Hartford,” Sigourney wrote for a living and published a poem titled “The Bride,” in which an observer of a newly married young woman chides those who would make light of this scene and casts marriage for women in terms that similarly evoke restraints placed on beasts of burden:

Mock not with mirth

A scene like this, ye laughter-loving ones;

The licens’d jester’s lip, the dancer’s heel—

What do they here? Joy, serious and sublime,

Such as doth nerve the energies of prayer,

Should swell the bosom, when a maiden’s hand,

Fill’d with life’s dewy flow’rets, girdeth on

That harness which the ministry of death

Alone unlooseth, but whose fearful power

May stamp the sentence of eternity.

At the end of “Title divine,” different women’s voices stroke with eerie possessiveness the “Melody” of the phrase “My Husband.” The voice in the final line seems to call much into question. David Porter calls the poem “a model of evasion, of language crafted to carry emotion without verifiable reference.” Sandra Gilbert concludes, “Surely this poem’s central image is almost the apotheosis of anguish converted into energy.” Helen Vendler calls this a “boast-poem,” and yet points out the absence of the first person pronoun.