Victory comes late –

Victory comes late –

And is held low to freezing

lips –

Too rapt with frost

To take it –

How sweet it would have tasted –

Just a Drop –

Was God so economical?

His Table’s spread too high

for Us –

Unless We dine on Tiptoe –

Crumbs – fit such little mouths –

Cherries – suit Robins –

The Eagle’s Golden Breakfast

strangles – Them –

God keep His Oath to Sparrows –

Who of little Love – know

how to starve –

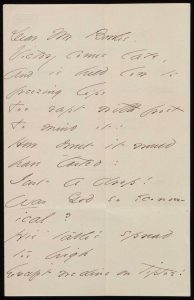

Link to EDA manuscript. Originally in Letter to Samuel Bowles, [1861] p. 1. Library ID: YCAL MSS 201. Courtesy of Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Library, Yale University, New Haven, CT. Later copied into Fascicle 34. First published in Poems (1891), 49, from the fascicle copy (B), with lines 12 and 14 divided into two lines each.

Dickinson originally sent this poem in a letter to Samuel Bowles, and though the dating of the letter and poem is unclear, some scholars believe it is an elegy for Frazar Stearns, whose death at the battle of New Bern shocked everyone in Amherst and particularly affected the Dickinson family. The poem closely replicates what Dickinson knew about the circumstances of Stearns’ death from reports and details she recounted to her Norcross cousins in Letter 255 quoted in full in the Biography section of the post.

The poem is an excellent example of Dickinson’s free verse poems, discussed in an earlier post on Meter. In her discussion of Dickinson’s use of free verse, Cristanne Miller diagrams this poem’s structure and concludes that it

maintains a rough iambic undertone, but the combination of highly irregular line lengths, no pattern of even- and odd-numbered syllables, and the unevenness of the meter prevent all sense of metrical regularity.

The lack of regularity, however, suits the poem’s ironic tone that questions the wisdom of a God who seems, in this untimely death, to have not kept his “vow.” In the second stanza, Dickinson alludes to two verses from the gospel of Matthew:

Matthew 6:26: Look at the birds of the air: They do not sow or reap or gather into barns–and yet your Heavenly Father feeds them. Are you not much more valuable than they?

Matthew 10:29: Are not two sparrows sold for a penny? Yet not one of them will fall to the ground apart from the will of your Father.

Barton Levi St. Armand notes that Stearns had an early conversion during the religious revivals in Amherst, but argues that Stearns had begun to share Dickinson’s “burned-child’s response to transforming religious fires,” which took the form of a

self-sacrificial fanaticism … [to] the Union cause, and he too courted death as both a test and a justification of his faith.

Not just the Congregational God, but the state comes in for critique in this poem. Does the image of “Eagle’s golden breakfast” suggest the Union government, whose symbol is the bald eagle? Shira Wolosky comments that the poem

moves from a concern with military to a concern with theological victory, and the latter subsumes the former.

Sources

- Miller, Cristanne. Reading in Time: Emily Dickinson in the Nineteenth Century. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2012, 114-15.

- St. Armand, Barton Levi. Emily Dickinson and Her Culture: The Soul’s Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984, 110-11.

- Wolosky, Shira. Emily Dickinson: A Voice of War. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1984, 61.