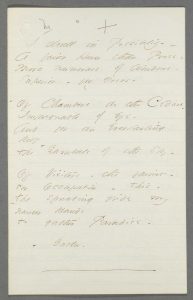

I dwell in Possibility –

I dwell in Possibility –

A fairer House than Prose –

More numerous of Windows –

Superior – for Doors –

Of Chambers as the Cedars –

Impregnable of eye –

And for an everlasting

Roof

The Gambrels of the Sky –

Of Visitors – the fairest –

For Occupation – This –

The spreading wide my

narrow Hands

To gather Paradise –

Link to EDA manuscript. Originally in Poems: Packet XIX, Fascicle 22, dated ca. 1862. First published in Further Poems (1929), ed. Bianchi and Hampson, 30, with the alternative adopted. Courtesy of the Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.

Dickinson copied this poem into Fascicle 22, also dated to 1862 and following Fascicle 21, which contained the previous two poems. The first poem in this fascicle is “A Prison gets to be a friend” (F456A, J652), which picks up the imagery of captivity, and the penultimate poem is “He fumbles at your Soul” (F477A, J315), a harrowing poem that ends with the hurling of an “imperial Thunderbolt – / That peels your naked soul,” an image that recalls the marvelous image, though in a more positive register, of the poet stunning herself with “Bolts of Melody,” from “I would not paint a picture.”

Readers have called this poem a “manifesto” that compares poetry, referred to obliquely as “Possibility,” to prose as an inferior dwelling place with decidedly inferior ventilation. The “cedars” referred to in the second stanza evoke a verse from Psalms 104:16: “The trees of the Lord are full of sap: the cedars of Lebanon which He hath planted,” and suggest the brimming, divinely ordained vitality of poetry.

“Gambrels” are “hipped roofs” (Webster’s) sloped on each side, which were traditionally used in building barns and could be seen in Amherst.

Here, in this poem, the homely and familiar become the architecture of the heavens. It is in this airy structure that the speaker can take up her genius and pursue her “Occupation,” which consists of “gather[ing] paradise,” even though her hands are “narrow” and small.

Here, in this poem, the homely and familiar become the architecture of the heavens. It is in this airy structure that the speaker can take up her genius and pursue her “Occupation,” which consists of “gather[ing] paradise,” even though her hands are “narrow” and small.

So much of Dickinson’s poetics can be illustrated by her equation of them with “possibility.” Still, we hear a darker note in the word “Impregnable,” which refers to the character of this dwelling as invisible. Yet, it is usually fortresses that are described as “impregnable,” so who is the enemy and where is the besieging army? The sexual connotation of this word cannot be avoided. Could Dickinson be suggesting that her dwelling is protected from invasion; that it has no male or masculine, impregnating source?

H. Jordan Landry argues the opposite, that though masculine power can be terrifying in Dickinson’s poems, the “power available in poetic inspiration is also posited as masculine.” The transcendence

of restrictive boundaries … initiated by the masculine is commensurate with a key goal of Dickinson’s poetics: the attainment of ‘Possibility.’

There is another way to look at it. In Anne Bradstreet’s poem, “The Author to her Book,” written after she first saw the volume of her poems published by her brother-in-law in London in 1650, she describes it deprecatingly as an “ill-formed offspring of my feeble brain,” turns it out of the house to manage on its own, and cautions:

If for thy father asked, say thou hadst none;

While this renders the book-child illegitimate, it also makes it completely and undeniably hers, a totally female creation.

Sources

Hallen, Cynthia, ed. Emily Dickinson Lexicon. Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University, http://edl.byu.edu/index.php, 2007.

Landry, Jordan H. “The Masculine Role.” An Emily Dickinson Encyclopedia. Ed. Jane Donahue Eberwein. Westport, CT.: Greenwood Press, 1998, 192-93.

Leiter, Sharon. Critical Companion to Emily Dickinson: A Literary Reference to her Life and Work. New York: Facts on File, 2007. 96-97.

Vendler, Helen. Dickinson: Selected Poems and Commentaries. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University, 2010, 222-24.