This week we explore Dickinson’s third letter to Thomas Wentworth Higginson, dated June 7, 1862. This letter is most commonly known for what biographer Richard Sewall calls

This week we explore Dickinson’s third letter to Thomas Wentworth Higginson, dated June 7, 1862. This letter is most commonly known for what biographer Richard Sewall calls

disavowals that have contributed as much as anything ever said about her to the legend of the shy genius

—most specifically, a seemingly definitive expression of Dickinson's disinclination for print publication (she says it's as “foreign to my thought, as Firmament to Fin”). The letter also notably ends with Dickinson’s famous, coy request:

But, will you be my Preceptor, Mr Higginson?

However, elements in this letter undermine Dickinson’s possible “posing” as needing a tutor and guide. This letter is significant for marking the beginning of what Dickinson, for the first time, denominates her “friendship” with Higginson. Friendship is a weighty word that implies not tutelage or preceptorship but a relationship of equality. And letters have historically been a special genre for friendship, by which writers send themselves in words to their special recipient.

In fact, Dickinson carefully chose Higginson as a correspondent. As a prominent literary figure, he was in a position to acknowledge and legitimate her as a poet. This letter also sets the tone for this friendship, which will last until Dickinson’s death in 1886. It records Dickinson's playful parrying and resistance of Higginson’s criticism of her poetry, which we have to infer from Dickinson’s responses, since all Higginson’s letters to her were either burned after her death or lost. As several studies of their relationship demonstrate, it’s not clear who was the student and who was the teacher!

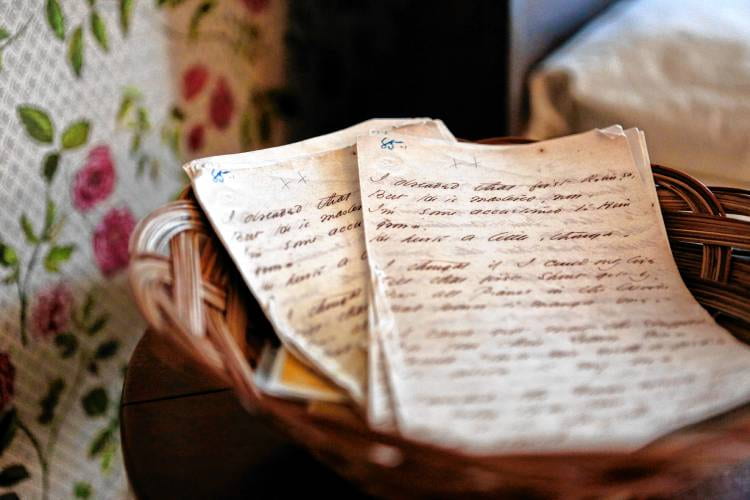

Exploring this letter, which has a poem embedded in it, also gives us the opportunity to consider it as an aesthetic object in its own right, and think about how Dickinson's prose and poetry interact. In the “Foreword” to a collection of essays about Dickinson’s letters, Marietta Messmer argues that her correspondence can “be regarded as her central form of public artistic expression.” Messmer cites pioneering work in this vein by scholars like Agnieszka Salska, who argues that Dickinson's letters

became the territory where she could work out her own style, create her poetic voice, and crystallize the principles of her poetics.

We will read this letter next to other poems written during this period that expand on its central themes of intoxication, illness, publication, and preceptors.

“The Virtues of Cold Water”

NATIONAL HISTORY

Springfield Republican, June 7, 1862, page 1

Review of the Week: “This has been the most g[illegible] week of the war–a week of victories and successes, which make us forget all previous blunders and disasters. The rebel army in front of Richmond has been beaten in a two days’ battle, Beauregard’s army has fled in fright and confusion from Corinth, the rebels have been driven back up the valley of the Shenandoah, and the ground lost last week more than recovered, and it looks now as if the field fighting is really over.”

“The General Situation,” page 1: “In connection with the victories won by our arms come reports of growing Union feeling at the South.”

“New England Matters,” page 1: “The lectures of Parson Brownlow have excited great interest at the various points which he has visited; and he had full houses and enthusiastic applause at Hartford and in this city. He paints this wicked rebellion in such strong colors as may suitably be used by one who has felt the halter around his neck and the iron entering his soul for the crime of loving his undivided country.”

Religious Intelligence, page 1: “Treason brutalizes priest as well as people. … Another reverend secesh, named Ely, distinguished himself by his outrages. After dinner he remarked to a young lady that he was going to Ball’s Bluff after trophies. He wanted some bones of the Yankee soldiers, in order to make finger rings, &c. to carry his presents to some of his female friends in Mississippi.”

Poetry: “Spring in New England” page 2, in rhyming couplets by J. R. Lowell

Original Poetry, page 6

“The Kiss” and “Love’s Good Night” by H. M. E. and “A Sonnet After F. G. T.” which refers to an apparently execrable sonnet that appeared in this month's Atlantic Monthly, and was called out by other commentators as well:

… Poor murdered language, lying still and stark;

Words that have somehow lost the vital spark;

As if the lexicon, in playful antic,

Shook them as from a dice-box,—new and old,

Nouns, adjectives and adverbs, more or less,

Just as it happened; so it is, I guess,

That, like a pebble in a ring of gold,

Lies a dead sonnet in the June Atlantic. F. H. C.

Hampshire Gazette, June 10, 1862

Local Intelligence –Northampton: “Another great success attended the lecture of [John B.] Gough last Tuesday evening. … The old temperance advocates were excited with delight, and even the lovers and users of intoxicating drinks were forced to accept his logic as conclusive and laugh at the exposures of their unmanly conduct. The closing portion of the lecture was an exceedingly beautiful picture of the virtues of cold water.”

There is another long column on page 1 about Gough’s lecture and the virtues of temperance in which the correspondent says,

we wish our poor brothers whom alcohol has almost destroyed could hear Gough.

Also, a short piece from “some curious letters” that were found in the post office at Norfolk when the Northern troops took possession. Among them was one from John Tyler [tenth president of the United States], dated October 6, 1860, which said, “Eight months ago I gave up the wine cup forever, to devote myself to my country until the end cometh.”

Literary, page 1: Recommends three books for children and gives the contents for The Westminster Review for April, the London Quarterly for April, Blackwood for May, and the newest Rebellion Record.

Other columns on page 1: “What is a ‘Gentleman,’” “Truth at Home,” “Unruly Milch Cows,” “Kindness to Animals,” “A Plea for the Skunk.”

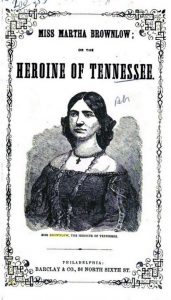

Amherst, page 2: “The eloquent John B. Gough will address the students by request, on Tuesday afternoon of Commencement week, in the Village Church. His subject will be ‘London.’” Amherst College, June 9: “We enjoyed a great treat last Saturday afternoon, listening to the heroic Parson Brownlow, from Tennessee. … The Parson’s daughter, the brave woman who defended the “Stars and Stripes” at the peril of her life against the savage hordes of rebeldom, is traveling with her father. She is a noble looking woman, and her outer bearing speaks for the great soul within.

Amherst College, June 9: “We enjoyed a great treat last Saturday afternoon, listening to the heroic Parson Brownlow, from Tennessee. … The Parson’s daughter, the brave woman who defended the “Stars and Stripes” at the peril of her life against the savage hordes of rebeldom, is traveling with her father. She is a noble looking woman, and her outer bearing speaks for the great soul within.

“I am in danger–Sir–”

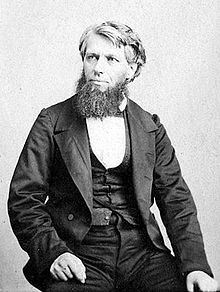

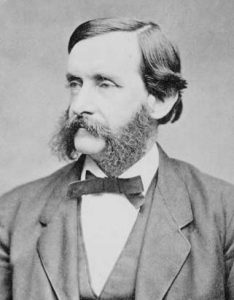

It is important to put Dickinson’s third letter to Higginson dated June 7, 1862 (L265) into the context of her state of mind and their earlier correspondence. In an earlier post, we discussed Dickinson’s first letter to Higginson, a prominent literary figure and public reformer. Written on April 15, after reading his “Letter to a Young Contributor” in that month’s Atlantic Monthly, she asked:

Are you too deeply occupied to say if my Verse is alive?

She enclosed four poems.

Higginson wrote back quickly, but because his letters to Dickinson were either burned at her death (on her request to Lavinia) or lost, we have only those she sent to him and have to infer what was in his letters from her responses. In her second letter on April 25, Dickinson thanks him for his “surgery,” implying that he critiqued her poems, and answers in oblique and winsome ways some of the questions he put to her about herself, her reading, her family and companions. She enclosed two or three more poems, including the masterful account of renounced passion, “There came a Day at Summer’s Full” (F325A, J322) .

On June 7, 1862, Dickinson responded to the second letter Higginson wrote to her, sometime after the end of April. We should note that instead of addressing him as “Mr. Higginson,” as she did in her second letter, this letter begins “Dear friend.” and ends, “Your friend / E Dickinson,” suggesting quite a leap in intimacy for the reputedly shy Dickinson. It also suggests an aspiration to, or even the assumption of, equality. Jason Hoope, who argues for the importance of this correspondence to Dickinson, notes that she regarded Higginson’s “surgery” on her poems “as heralding literary legitimacy. The inevitable sincerity of evaluation in and of itself—regardless of its content—is ‘justice,’ as the third letter makes clear”:

Your second letter surprised me, and for a moment, swung – I had not supposed it. Your first-gave no dishonor, because the True-are not ashamed – I thanked you for your justice -but could not drop the Bells whose jingling cooled my Tramp-Perhaps the Balm, seemed better, because you bled me, first.

Whereas in the first letter, Dickinson asks Higginson to “tell me what is true,” here, as Hoope notes, Dickinson “asserts her own membership among ‘the True.’” This letter also reprises important themes from the two earlier letters, such as poetry as/and illness, her thinking about print publication and fame, and her eagerness for an interlocutor and confidante, a “friend.” We know from her letter of April 25 that Dickinson recently had been ill when she says, I “write today, from my pillow.” (L261). We also know that her close friend, Samuel Bowles, the editor of the Springfield Republican, had been away since Spring on a European tour for his health, and that Dickinson had been missing him keenly. Claiming to have exhausted language’s capacity to describe how moved she was by “The ‘hand you stretch me in the Dark,’” Dickinson embeds a poem into the letter, “As if I asked a common Alms” (F14, J323).

Although Alfred Habegger observes that “the letters to Higginson enacted the poet’s fondness for self-dramatization,” he also suggests that “The isolation she claimed was by no means wholly fictive.” Still, when her brother Austin read the 1891 Atlantic essay in which Higginson excerpted and commented on Dickinson’s letters,

he says Emily definitely posed in those letters. … The fraternal view had its blind spots, like the paternal condescension toward the female mind. These familial male superiorities help explain many things, including the poet’s quest for authoritative “tutors” and “masters” outside her home.

Reflection

Ivy Schweitzer

Two Poems

Southwest Corner

The room– spare and bright.

Carlyle, Browning, and Eliot watch from the walls,

A tiny desk for weighty work.

The Franklin stove gave private warmth,

Writing into the night, even–

deliciously–till dawn.

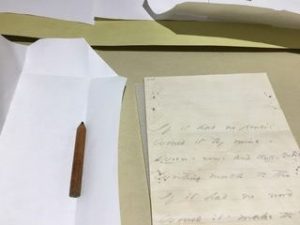

Later, pencils, scribbling on

Scraps stashed in pockets,

Envelopes splayed like butterflies

Straying through chores,

Winged +gleanings of song.

But the geranium on the sill?

Flamboyant blossoms coaxed in shivers,

For window musing, stroking sueded leaf,

heady scent of the Orient and heat.

Then, shimmering grail of pilgrimage

The white dress

Surprisingly petite, front buttons requiring

No help. Too busy plumbing eternity for fussing.

Through the hush of admiration

–rustle of muslin, and

Glimpsed escaping behind the bedroom door

Pinned auburn hair

Bold, like the chestnut burr

Depthless eyes

Like the sherry in the glass the guest leaves.

+ edifice

Identification

Spellbound I tail it,

coral shard

shifting too deliberately

in the rubbled shallows

I prowl between reef and shore.

First, tiny whirling fins appear,

little brooms propelling

a wedge-shaped body

brindled with three dark blotches

like bruises or spilled ink.

Then a face, square and wide,

with large unlidded eyes

and yellow spikes whiskering

a plated, smirking mouth.

For a sickening moment our gazes

lock–I am hooked and held.

Later, dry and safely landed,

I find staring out from a page

of the identification book:

Chilomycterus antillarum,

the webbed burrfish,

aka spiny boxfish, blowfish, balloonfish, globefish, hedgehog fish, swelltoad,

evil twin of the porcupine puffer

who delights us with its

Disney waifishness.

I add it to my life list

but it bewitches

my thoughts, twitching up,

talisman of depths,

never letting me forget

how in its world

I am forced to surrender

the engineering miracle of knees

kicking stiff-legged

tipped with rubber fins.

bio: Ivy Schweitzer is the editor of White Heat.

Sources:

Overview

Messmer, Marietta. “Foreword.” Reading Emily Dickinson's Letters: Critical Essays. Eds. Jane Donahue Eberwein and Cindy MacKenzie. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2009, vii-x, viii.

Salska, Agnieszka. “Dickinson’s Letters.” The Emily Dickinson Handbook. Eds. Gudrun Grabher, Roland Hagenbüchle, Cristanne Miller. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1998, 163-80, 168.

Sewall, Richard. The Life of Emily Dickinson. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1980, 553.

History

Hampshire Gazette, June 10, 1862

Springfield Republican, June 7, 1862

Biography

Habegger, Alfred. My Wars are Laid away in Books. New York: Random House, 2001, kindle version.

Hoope, Jason. “Personality and Poetic Election in the Preceptual Relationship of Emily Dickinson and Thomas Wentworth Higginson, 1862-1886.” Texas Studies in Literature and Language. 55, 3 (Fall 2013): 348-387, 358.