“What do I think of glory —”

This week we build on last week's post on a remarkable woman by picking up on a snarky comment from the February 22 Springfield Republican’s “Books, Authors and Art” section:

Miss Evans (George Eliot) promises a new novel this spring; but judging from her last (Silas Marner) her glory has departed; Happy marriage and rest from doubt and scandal take the passion out of women geniuses. Adam Bede and the Mill on the Floss were born of moral trial and heart hunger; and the reading world must find their compensation–if they can–for the falling off in their successors in the belief that the writer is content and at peace.

The forthcoming novel referred to here is Romola, a historical tale set in fifteenth-century Florence, which appeared in serial form in Cornhill Magazine from July 1862 to August 1863 and was published as a book in 1863. Note that the writer of this article accepts the fact of Eliot’s artistic “glory,” but sees domestic happiness as antithetical to “women geniuses.” In fact, Eliot’s acknowledged masterpiece, Middlemarch, was still to come in 1871-72. Dickinson will rave about it in a letter to her Norcross cousins who solicit her opinion, using the same word, “glory,” as in the Republican’s dismissive comment:

What do I think of Middlemarch? What do I think of glory – except that in a few instances this “mortal has already put on immortality.”

George Eliot is one. The mysteries of human nature surpass the “mysteries of redemption,” for the infinite we only suppose, while we see the finite. … (L389, late April 1873).

Dickinson’s reverence for Eliot as woman and writer is well known (see Sources). Of the three portraits Dickinson hung in her room, one of them was a picture of Eliot, the only woman in the group. Although Dickinson never met the English author, she considered her a friend and, certainly, a role model. When Dickinson heard of Eliot’s death in December 1880, she was bereft, and wrote to her intimates about “Grieving for ‘George Eliot’” (L683), calling her “my George Eliot” (L710; emphasis hers). In a letter to Samuel Bowles, dated late November 1862 (L277), Dickinson alludes to an image from Eliot’s novel, Mill on the Floss, which she was probably reading during this time.

Eliot was not the only “woman of genius” Dickinson admired and identified with in terms of their shared struggle to be recognized and accepted. Eliot chose to publish under a male pseudonym, like the Brontë sisters before her, in order to evade prevailing cultural attitudes that trivialized or dismissed women’s artistic productions. Attitudes like the one asserted by the Republican, that women could only achieve genius if they were motivated by “moral trial” and “heart hunger.” But if they found some modicum of domestic happiness or stability, the quality of their work must inevitably fall off. That is, women could be artists, somehow transcending the limitations of gender, but not women at the same time.

In fact, Anglo-American culture has not been good to its women of genius, especially its poets. The first poet to publish a book of poetry written in the North American colonies was Anne Bradstreet (1612-1672), the educated daughter and wife of men who both served as governors of the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

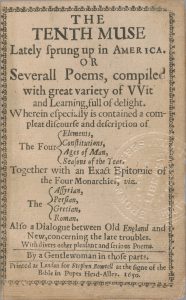

But when her brother-in-law carried her book of poems to London to be published in 1650, it was titled, The Tenth Muse, lately Sprung up in America. High flown praise, but muses are not writers. This brother-in-law felt it necessary to engage a bevy of notable literary men to write prefatory poems and endorsements for this somewhat unusual volume, and he himself wrote a long letter confirming that, indeed, this was the work of a woman “honoured, and esteemed where she lives for … her exact diligence in her place.” [editor's emphasis]

But when her brother-in-law carried her book of poems to London to be published in 1650, it was titled, The Tenth Muse, lately Sprung up in America. High flown praise, but muses are not writers. This brother-in-law felt it necessary to engage a bevy of notable literary men to write prefatory poems and endorsements for this somewhat unusual volume, and he himself wrote a long letter confirming that, indeed, this was the work of a woman “honoured, and esteemed where she lives for … her exact diligence in her place.” [editor's emphasis]

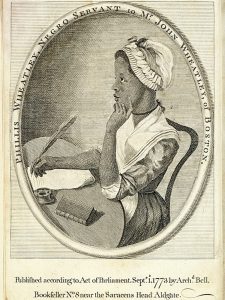

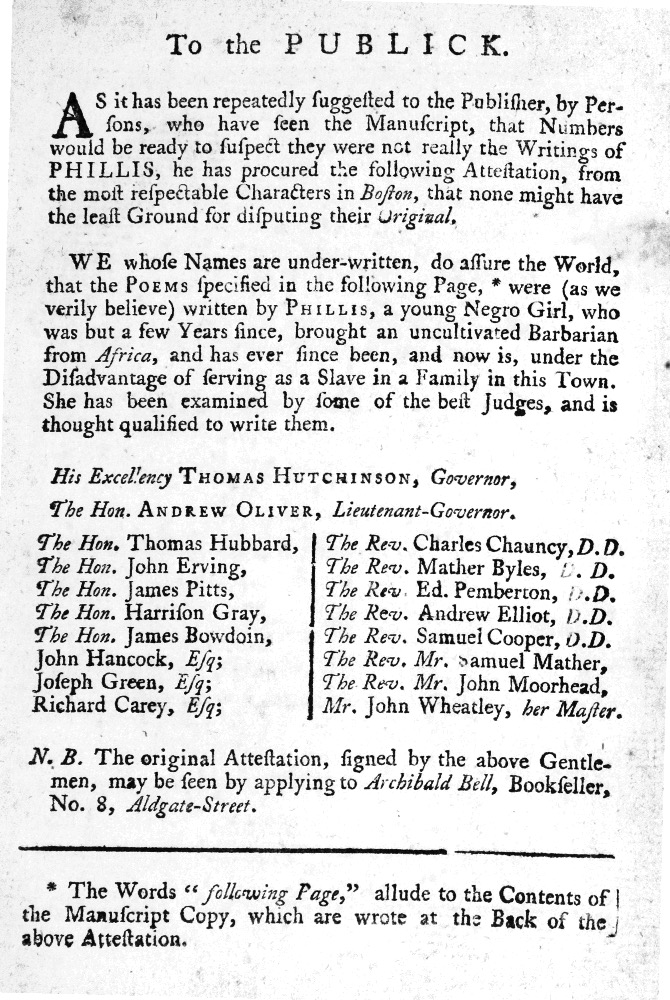

Over a hundred years later, the owners of the enslaved child prodigy, Phillis Wheatley (1753-1784), tried to get her poetry published in Boston in the late 1760s.

To do so, they not only appended a letter of verification to the volume, assuring a doubting public that this young African woman had indeed written poems that emulated Alexander Pope, but they also included a statement signed by a troop of prominent men who affirmed Wheatley's authorship. At the top of this list was the Governor, the Lieutenant-Governor and a host of Boston worthies, including a man who would soon make the act of signing his name the signal act of rebellion: John Hancock! Nevertheless, Wheatley had to take her manuscript to London for publication.

One of the reasons for this treatment is the historical gendering of genius, enshrined in the Roman origin of the word itself, which connotes the male “essence” or “gens” that is passed down through the male lines of a family. Romantic and Victorian ideas of genius look back to the Greeks, who argued that certain men could be the medium for ideas of the divine, a creativity that looked a bit like madness, because they were, according to the reigning medical theory of humors, warm and dry.

Women, by contrast, were wet and cold on account of having wombs; their madness was not creative but procreative—that is, hysterical (from “hyster,” the Latin word for womb). Thus, the rhetoric of genius that praised “feminine” qualities in male artists, like intuition and emotionality, excluded women and supposedly “primitive” peoples on the basis of biology and psychology. Some thinkers, like the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860), developed the idea of the artist as a “third sex” or androgyne, who combined “feminine” receptivity and “masculine” will. But this led to different treatments of melancholia, a state closely associated with genius; in men, it was a channel to sublime revelation, but in women it led to weakness and mental illness.

In her ground-breaking feminist analysis of genius, A Room of One's Own (1929), Virginia Woolf (1882-1941) conducted a telling thought experiment. She imagines that Shakespeare had a sister named Judith, who was just as brilliant and ambitious as her brother, and tries to construct a life for her. After considering all the social constraints placed on Englishwomen of the sixteenth century, Woolf concludes that

a highly gifted girl who had tried to use her gift for poetry would have been so thwarted and hindered by other people, so tortured and pulled asunder by her own contrary instincts, that she must have lost her health and sanity to a certainty.

Not surprisingly, in this tale Judith ends up pregnant, abandoned and, unable to support herself, commits suicide.

Judith’s story is not so far from that of women of genius in the nineteenth century. Margaret Fuller (1810-1850), hailed by her contemporaries as a rare intellectual and artist, condemns the treatment of women of genius of her day in her remarkable study, Woman in the Nineteenth Century (1845). Notice the connection in this passage by Fuller to Dickinson’s use of bird imagery for Sue and herself:

Plato, the man of intellect, treats Woman in the Republic as property, and, in the Timaeus, says that Man, if he misuse the privileges of one life, shall be degraded into the form of Woman; and then, if he do not redeem himself, into that of a bird. This, as I said above, expresses most happily how anti-poetical is this state of mind. For the poet, contemplating the world of things, selects various birds as the symbols of his most gracious and ethereal thoughts, just as he calls upon his genius as muse rather than as God. But the intellect is cold and ever more masculine than feminine; warmed by emotion, it rushes toward mother earth and puts on the forms of beauty. Women who combine this organization [the electrical, the magnetic] with creative genius are very commonly unhappy at present. They see too much to act in conformity with those around them, and their quick impulses seem folly to those who do not discern the motives. This is an usual effect of the apparition of genius, whether in Man or Woman, but is more frequent with regard to the latter, because a harmony, an obvious order and self-restraining decorum, is most expected from her.

Then, women of genius, even more than men, are likely to be enslaved by an impassioned sensibility. The world repels them more rudely, and they are of weaker bodily frame.

It is not hard to see why a woman like Dickinson, who knew herself to be touched with brilliance, would choose not to be an active member of a world that rudely “repels” women of genius.

“God spared my life, and for what …”

Springfield Republican, March 8, 1862.

INTERNATIONAL NEWS

“Our position abroad is as good as we could desire.” Reports are that “the secession cause is in fact dead in Europe” and those backers in the British and French governments have accepted pending defeat of the South.

The war in Mexico concludes with “an armistice and negotiations for settlement.” The negotiations could continue for months, but the Union is not interested in rejoining the conflict, even if by chance it does start up again.

Trouble lies with Russia, however. Serfs criticize the law that gives them their freedom, because they have to buy their freedom, which is impossible for nearly all under serfdom. Poland and Finland seek to use this weak spot in Russian governing to gain independence. Germany, Hungary, Italy, Prussia, and Austria struggle with dissatisfaction in ruling powers and widespread imperial governments, and the Roman Catholic church is in turmoil due to an unstable Pope in times of war.

NATIONAL NEWS

Review of the Week: Progress of the War. “This week has been marked by important progress with little fighting,” says the Springfield Republican, and Union General Scott says “that the war is over and there is nothing to do but to clear up and prepare for peace, and the recent national successes at the West would seem to be decisive of the final result, so far as can now be seen.”

The “rebels” are retreating, cornered, or preparing to fight their last fights, and the Union has occupied most of the South by now. “Tennessee will soon quietly occupy its old position in the Union,” and “the confederate leaders at Richmond are represented to be in a state little short of panic.” [NB: Tennessee was the last state to leave the Union and the first to rejoin, but not until July 24, 1866. The Republican's comments show how overly optimistic the North was at this point.]

From Washington. The paper reports that the South had known about the decisive capture of Harper’s Ferry on Monday, but Southern newspapers were barred from printing such an update on the War, presumably to hide it from the public.

Confiscation and Emancipation. Illinois Senator Trumbull proposed a bill for the “confiscation of the property and the emancipation of the slaves of rebels,” a controversial move that has people asking what the rights of southerners are.

Senator Trumbull maintains that full war laws apply, and that the South is to be treated like an enemy nation with total destruction possible, but to lessen such a harsh punishment towards the rebels, that confiscation and emancipation was enough, and to treat them as “belligerents” was enough, at least until they could possibly be tried for treason.

“Suggestions for the Crisis.” This column debriefs some lessons learned, reasons for war, and what should happen in the event of another uprising. The author notes that starting the war in the spring was a good move for the Union considering the paralyzing winters the North experiences, and that the South had produced “few great men in this generation.” They also try to tease out the exact reason for the rebellion, but can’t quite find it, resolving to label it a power grab of the dying Southern power.

“The Dark Side of the Picture.” This letter from a Northern officer who was at Fort Donelson shows the “terrible realities of war.” He recounts the number of dead, the outcome, and the “wholesale slaughter” that left only seven out of 85 men alive in his company:

Do not wonder, dear father, that I am down-hearted. My boys all loved me, and need I say that, in looking at the poor remnant of my company—the men that I have taken so much pains to drill, the men that I thought so much of—now nearly all in their graves—I feel melancholy. But I do not complain; God spared my life, and for what, the future must tell.

“Was I the little friend —”

This week brought the sad news of the the death of the infant Edward Dickinson Norcross, on March 6. He was the son of Alfred and Olivia Norcross, Dickinson's maternal uncle and aunt.

Also this week, Dickinson writes a letter to Mary Bowles, the wife of Samuel Bowles, about accidentally sending Mr. Bowles a note to complete an “errand” for her, forgetting he left for Washington on the first of the month.

She worries that Mary instead did it for her, and it “troubled” her, and if Mary could “just say with your pencil – ‘it did’nt tire me – Emily’” she would cease her worries, as she “would not have taxed [Mary] – for the world -” Dickinson also asks about the new baby Charlie, and says she

sends a rose – for his small hands. Put it in – when he goes to sleep – and then he will dream of Emily – and when you bring him to Amherst – we shall be “old friends.”

Mary was a close friend of Dickinson, who frequently wrote letters to her, but received next to none back (the reply Dickinson asks for in the above letter “will be the first one – you ever wrote me -” she says). In editing some of Dickinson’s letters and poems, Mabel Loomis Todd switched the addressee from Sue to Mary to make their correspondence look more extensive and diminish the importance of Sue in Dickinson's life. In the above letter, Dickinson plaintively asks Mary, “yet – was I the little friend – a long time? Was I – Mary?”

This week, Dickinson also writes to Frances Norcross, one of two young Norcross cousins she adored and corresponded with throughout her life, about her sister Vinnie’s illness:

Poor Vinnie has been very sick, and so have we all, and I feared one day our little brothers would see us no more, but God was not so hard.

She also mentions that spring is supposed to be coming soon, but that this March has been particularly hard, with the Northeast hit lately with violent winter weather.

Reflection

Ivy Schweitzer

For my women friends who are all geniuses!

For my women friends who are all geniuses!

Undammed

She is a neighbor and a painter,

mother of a wild red-headed girl

friends with my son

so long ago

calling to say she dreamt

of me in a café somewhere

hair wavy and golden

and I was sad, she said,

so sad, she had to call

though we are not close

how it flooded her night

snagged on the branches of sleep

and I am dumbstruck,

appalled by the mutinous grief

breaching my edges and

rushing into the ruts of the world

and I say yes,

I am sad and sorry to come

uninvited, and we talk

of the wild red-headed girl who works

at a women’s clinic in Texas,

facing protesters every day,

and my son dwelling in half-life

and our own lives as artists in this time

of profit and fools

and though nothing changes

I feel myself ebb as a tide

back into its almost

manageable course.

Bio: Ivy Schweitzer is the creator and editor of White Heat.

Sources

Overview

Battersby, Christine. Gender and Genius: Towards a Feminist Aesthetics. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1989.

Bradstreet, Anne. The Tenth Muse lately Sprung up in America … London, 1650. Early English Books Online.

Freeman, Margaret H. “George Eliot and Emily Dickinson: Poets of Play and Possibility.” The Emily Dickinson Journal. 21.2 (2012): 37-58.

Fuller (Ossoli), Margaret. Woman in the Nineteenth Century and Kindred Papers Relating to the Sphere, Condition and Duties, of Woman. Project Gutenberg EBook #8642. Section on “Tune the Lyre.”

Gee, Karen Richardson. “‘My George Eliot’ and My Emily Dickinson.” The Emily Dickinson Journal 3.1 (1994): 24-40.

Heginbotham, Eleanor Elsen. “‘What do I think of glory—’ Dickinson’s Eliot and Middlemarch.” The Emily Dickinson Journal 21.2 (2012): 20-36.

Wheatley, Phillis. Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral. London, 1773.

Historical

Springfield Republican, volume 89, number 10. Saturday, March 8, 1862.

Biographical

Emily Dickinson’s Correspondences with Frances and Louise Norcross, DEA

Emily Dickinson’s Correspondences with Mary Bowles, DEA

Johnson, Thomas, editor. The Letters of Emily Dickinson, 2 vols. Belknap Press, 1958.

Leyda, Jay. The Years and Hours of Emily Dickinson. Yale University Press, 1960.

Smith, Martha Nell, and Ellen Louise Hart, editors. Open Me Carefully: Emily Dickinson's Intimate Letters to Susan Huntington. Wesleyan University Press, 1998.