This week’s post takes its inspiration from the June 1862 issue of the Atlantic Monthly, which printed two articles related to health and illness: Thomas Wentworth Higginson’s editorial on “The Health of Our Girls” and Henry David Thoreau’s essay, “Walking.” In April, Dickinson began a correspondence with Higginson in which she invoked illness both explicitly—“I was ill – and write today” (L261) and “I felt a palsy” (L265)—and implicitly in her language about her writing, with medicalized terms like “Balm” and “spasmodic” (L265).

This week’s post takes its inspiration from the June 1862 issue of the Atlantic Monthly, which printed two articles related to health and illness: Thomas Wentworth Higginson’s editorial on “The Health of Our Girls” and Henry David Thoreau’s essay, “Walking.” In April, Dickinson began a correspondence with Higginson in which she invoked illness both explicitly—“I was ill – and write today” (L261) and “I felt a palsy” (L265)—and implicitly in her language about her writing, with medicalized terms like “Balm” and “spasmodic” (L265).

Pointing out that editor Thomas Johnson dated 366 poems to 1862, biographer Richard Sewall considers Dickinson’s remarkable poetic inspiration and production during a time when she was in “such a deplorable emotional condition as is often hypothesized.” He observes, it

Pointing out that editor Thomas Johnson dated 366 poems to 1862, biographer Richard Sewall considers Dickinson’s remarkable poetic inspiration and production during a time when she was in “such a deplorable emotional condition as is often hypothesized.” He observes, it

is hard to see how she could have had the strength to put mind to matter or pen to paper, let alone write poems of much coherence and power.

In fact, many scholars have attempted to figure out just what was going on in Dickinson’s life health-wise, while “the difficulty with her eyes is still a mystery.” Explanations range from John Cody’s psychosomatic Freudian prognoses to investigations by Sewall and an ophthalmologist, who noticed in “the famous daguerreotype of Dickinson taken at Mount Holyoke Female Seminary,” that her right cornea “deviated as much as fifteen degrees from true.” James Guthrie notes that Dickinson traveled twice to Boston two years later to see Dr. Henry Williams, an ophthalmologist. Though a diagnosis is now impossible, Guthrie speculates that

in this struggle, poetry functioned as an extension of herself, an alternative mode of perception that took the place of her injured eyes and which was equally capable of revealing the truth to her.

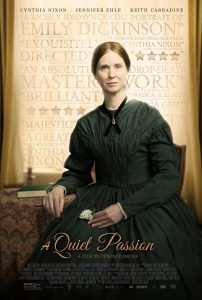

Interest in Dickinson’s health persists in contemporary circles. Director Terence Davis gave it ample screen time in his 2016 biopic A Quiet Passion. This week’s post situates Dickinson’s health in the commentaries of two contemporary writers, Higginson and Thoreau, and in her own poems from around 1862 about illness and health.

Interest in Dickinson’s health persists in contemporary circles. Director Terence Davis gave it ample screen time in his 2016 biopic A Quiet Passion. This week’s post situates Dickinson’s health in the commentaries of two contemporary writers, Higginson and Thoreau, and in her own poems from around 1862 about illness and health.

“The Health of Our Girls”

NATIONAL HISTORY

Springfield Republican, May 31, 1862, page 1

Progress of the War.

This has been the most extraordinary week of the whole war—a week of needless defeat and retreat, and of sudden panic and quick reassurance. Under the misapprehension that the capital was again in danger there has been another outburst of popular patriotism scarcely less vehement than that of April of last year, and the two hundred thousand volunteers needed to fill up the ranks of our decimated armies will come forward at once, and the government be obliged to say, “Hold, enough!” almost before its new summons to arms has been proclaimed through the country.

Springfield Republican, May 31, 1862, page 1

Cotton and Consumption.

Dr. Alfred Booth of Lowell, formerly of this city, has published an article broaching the novel theory that the wearing of cotton next the skin is a cause of consumption. If this should be confirmed the destruction of King Cotton may prove a great blessing instead of an evil. Dr. Booth’s theory is at least ingenious.

Springfield Republican, May 31, 1862, page 2

Books, Authors and Art.

Dogs and horses receive a great many ideas, both detached and associated, but they are incapable of generalizing; so that Max Muller is substantially right when he says: “No animal thinks and no animal speaks, except man. Language and thought are inseparable. Words without thought are dead sounds; thoughts without words are nothing. To think is to speak low; to speak is to think aloud. The word is the thought incarnate.”

Springfield Republican, May 31, 1862, page 3

Emancipation at War.

A letter from Gen. Fremont’s camp in Western Virginia relates the following significant incident:

The presence and passage of our army in the country is having the effect of settling the slavery question here, for emancipation follows its path. I have talked with many of these poor negroes, and find them singularly intelligent … They are of great value to us in many ways, especially as guides, and the scouts tell me that there has never been an instance of false or even incorrect information derived from them.

Springfield Republican, June 7, 1862, page 3

The poetry of the June Atlantic is all good with one exception; very good, with two. Of its prose, the first essay, on Walking, does more to unfold the characters and habits of its author, the late gifted eccentric Henry D. Thoreau, than any ordinary biography would have done;—Thoreau, who was emphatically a man of today, a student of “that newer testament, the Gospel according to the present moment;” and who after sauntering through a brief but happy life, has passed a la Sainte Terre, and will return no more. … Mr. Higginson’s article upon feminine health provokes a feeling of antagonism. He seems to ignore the fact that the brute vigor of the peasant woman is absolutely incompatible with culture and refinement, and that the scimitar of Saladin must keep to its graceful feats, and not attempt to deal the sledge-hammer blows of the heavy battle-ax of Richard. Moreover, physiologists are wont to confine themselves to material agencies, and yet there is an immaterial hygiene that affects, more vitally than we are fond of admission, “the health of our girls.”

Hampshire Gazette, June 3, 1862, page 2

The Emancipation and Confiscation Acts.

These two most important measures of the government came up in the House of Representatives last week, and the confiscation bill was passed by a majority of twenty, while the emancipation bill was lost by four votes. Both bills are published in another column. The people of Massachusetts are anxious that measures should be adopted by which some sort of punishment shall be meted out to the rebels, and they regret exceedingly that the bill for the emancipation of the slaves of rebels has failed.

Hampshire Gazette, June 3, 1862, page 2

Amherst.

The Selectmen have appointed Daniel Converse for the South part, and Marquis F. Dickinson for the North part, Special Police, to enforce the dog law. Mr. Converse canvassed the South Parish Wednesday and had 10 dogs licensed on his route, and all but four in that parish are now registered, and those were allowed three days grace, on account of the absence of the owners. … [Marquis F. Dickinson (1840-1915) was born in Amherst, graduated from Amherst College and Harvard Law School, and was a prominent Boston attorney, but does not seem to be directly related to the Dickinson's of the Homestead.]

Thomas M. Brown has been lecturing on temperance in Amherst, North Amherst, and other places adjoining—Dodge had a large audience at his concert in Amherst.

“Thoreau and Higginson on Health”

“I wish to speak a word for Nature …” -Henry David Thoreau, Atlantic Monthly, June of 1862

The June 7th printing of the Springfield Republican directs its readers’ attention to the Atlantic Monthly, reviewing columns by Henry David Thoreau and Thomas Wentworth Higginson (page 3). “Walking,” by the “late gifted eccentric” Thoreau, is said to “unfold the characters and habits of its author.” “The Health of Our Girls,” Higginson’s piece, on the other hand, “provokes a sense of antagonism.” The contemporary reader might also take issue with Higginson’s anachronistic arguments about women’s health, though writing about the topic at all was considered progressive for his time. Whatever the Springfield Republican has to say in review of this month’s Atlantic, it was certainly an issue to pique Dickinson’s interest, both for her focus on nature and her newfound relationship with Higginson.

In “Walking,” Thoreau makes a case for

Nature, for absolute freedom and wildness, as contrasted with a freedom and culture merely civil,—to regard man as an inhabitant, or a part and parcel of Nature, rather than a member of society.

He feels there are “enough champions of civilization” and too few of Nature. He notices the “subtle magnetism of Nature,” a force that Dickinson has documented well. He does not, however, share her love for gardens, but instead, for walking:

yes, though you may think me perverse, if it were proposed to dwell in the neighborhood of the most beautiful garden that every human art contrived, or else of a dismal swamp, I should certainly decide for the swamp.

Thoreau, perhaps unlike Dickinson, places the garden on the order of “civilization,” the management and pruning of “Nature,” and is therefore surpassed by the wild, untouched swamp.

Around the same time that Higginson was in correspondence with Dickinson, he published his editorial, “The Health of Our Girls,” in the Springfield Republican, addressing what he saw as a decline in the vigor of New England women. Notably, Dickinson’s first three letters to Higginson (on April 15th, 25th, and June 7th) make use of the metaphors and metonyms of health.

Are you too deeply occupied to say if my Verse is alive?

she writes in the first, as if to put her poetry on the hospital bed (L260). In the second, she thanks him for his “surgery,” writing from her pillow because she is “ill” (L261). In the third, she claims that his “Balm, seemed better” because he “bled her first” (L265). That her rhetoric affords him the role of a poetic doctor becomes all the more relevant when he publishes his piece on the health of women. His all-knowing assertion of what’s best for women’s health is reflected in his correspondence with Dickinson and his editorial comments on her poetry. At the same time that he performed surgery on her poetry, she was “ill” and found some relief in writing.

Higginson frames his argument within an American context, asserting that “Nature is aiming at a keener and subtler temperament in framing the American” due to a “drier atmosphere” which might produce a “higher type of humanity.” Female health, however, is determined largely by changing social conventions. He then cites the obstacles:

What use to found colleges for girls whom even the high-school breaks down, or to induct them into new industrial pursuits when they have not strength to stand behind a counter? How appeal to any woman to enlarge her thoughts beyond the mere drudgery of the household, when she “dies daily” beneath the exhaustion of even that?

The “disease” of American women, as he calls it, is deeply embedded in the social, the “elevation of the mass of women to the social zone of music-lessons and silk gowns” such that they forgo the “rustic health” of field-labor and agriculture. Like Thoreau, he privileges “walking” which he sees as a “rare habit among our young women.” He offers a panorama of possible solutions—forms of exercise that he finds well-suited to women—such as swimming, rowing, and riding horses. Of the condition of women’s health in the US, he concludes:

Morbid anatomy has long enough served as a type of feminine loveliness; our polite society has long enough been a series of soirées of incurables. Health is coming into fashion.

Reflection

Giavanna Munafo

This week’s post and poems invite us to consider the complex ways that Dickinson’s health, especially her “chronic optical illness," influenced her poetry, is made visible or evident there, and/or might inform our understanding of her work from this period.

This week’s post and poems invite us to consider the complex ways that Dickinson’s health, especially her “chronic optical illness," influenced her poetry, is made visible or evident there, and/or might inform our understanding of her work from this period.

In response, I was called back to a poem very much of our current time and concerned with one of the greatest health crises of modern life, the AIDS epidemic. In “Heartbeats,” the poet and novelist Melvin Dixon asserts through poetic utterance his own stuttering process of coming face to face with illness and suffering. Dixon died at 42 of complications from AIDS. Every step of the way “Heartbeats” insists, in recurring imperative commands, on the tending of the body and its fitness while simultaneously cataloguing the determined, ever-escalating throws of its failure in the face of a persistent, fatal disease.

The battery of the poem’s repetitive two-syllable sentences in relentless couplets, along with the poem’s guttural rhythmic music, hammer home its story of ever-persistent symptoms and the speaker’s equally stubborn drive to fend them off. The final couplet, starting with a reprieve from the poem’s headstrong anti-sentimentality — “Sweet heart.” — introduces a tension similar to the one Guthrie notes in Dickinson’s work, giving possibility with one hand while taking it away with the other.

Lastly, another connection across the years worth noting, and one that remains a pressing matter today, is concern about public health in the specific context of subjugated populations put under medical scrutiny, populations to be managed or controlled. In Dickinson’s day (and, of course, sadly too often still), women were to be diagnosed and managed, and in our time those most devastated, and for far too long abandoned, by private and public neglect of the AIDS epidemic — gay men, intravenous drug users, and the poor — were and remain under the microscope, literally in medical terms and metaphorically in terms of their rights as citizens and fully human members of our communities.

Heartbeats

by Melvin DixonWork out. Ten laps.

Chin ups. Look good.Steam room. Dress warm.

Call home. Fresh air.Eat right. Rest well.

Sweetheart. Safe sex.Sore throat. Long flu.

Hard nodes. Beware.Test blood. Count cells.

Reds thin. Whites low.Dress warm. Eat well.

Short breath. Fatigue.Night sweats. Dry cough.

Loose stools. Weight loss.Get mad. Fight back.

Call home. Rest well.Don’t cry. Take charge.

No sex. Eat right.Call home. Talk slow.

Chin up. No air.Arms wide. Nodes hard.

Cough dry. Hold on.Mouth wide. Drink this.

Breathe in. Breathe out.No air. Breathe in.

Breathe in. No air.Black out. White rooms.

Head hot. Feet cold.No work. Eat right.

CAT scan. Chin up.Breathe in. Breathe out.

No air. No air.Thin blood. Sore lungs.

Mouth dry. Mind gone.

Six months? Three weeks?

Can’t eat. No air.

Today? Tonight?

It waits. For me.

Sweet heart. Don’t stop.

Breathe in. Breathe out.

Bio: Giavanna Munafo teaches in Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies at Dartmouth College. She is also a volunteer crisis counselor and advocate and does consulting work focused on diversity and equity. Giavanna’s poems have appeared in E.Ratio, Redheaded Stepchild, Slab, Talking Writing, The New Virginia Review, Bloodroot Literary Magazine, and The Nearest Poem Anthology (Ed. Sofia Starnes). She holds a BA and PhD from the University of Virginia and an MFA from the University of Iowa. Giavanna lives in Norwich, Vermont.

Sources:

Overview

Sewall, Richard. The Life of Emily Dickinson. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1980, 606.

Guthrie, James R. Emily Dickinson's Vision: Illness and Identity in Her Poetry. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1998, 8-9.

History

Hampshire Gazette, June 3, 1862

Springfield Republican, May 31, June 7, 1862

Biography

Guthrie, James R. Emily Dickinson's Vision: Illness and Identity in Her Poetry. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1998, 8-9.

Higginson, Thomas Wentworth. “The Health of Our Girls,” Atlantic Monthly, June 1862.

Thoreau, Henry David. “Walking,” Atlantic Monthly, June 1862.