“Emily Dickinson: a Mo Ho”

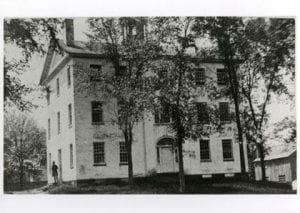

This week in 1862 marked the 25th anniversary of the founding of Mount Holyoke Female Seminary by the redoubtable Mary Lyon. It would eventually become Mount Holyoke College, a prestigious women’s college in South Hadley, Massachusetts. The Hampshire Gazette noted the significance of this event:

At the time she instituted the seminary, there were in the country one hundred and twenty colleges for boys, but not one for girls, where they could get the highest form of education.

In fact, higher education and, thus, most professions in the United States were closed to women until Oberlin College in Ohio began to admit women, as well as African Americans, in 1833. Although attitudes favoring women’s education and, thus, their full civil rights were still in the minority at this time, Enlightenment thought and Republican ideology encouraged educating women who would then pass on Republican ideals to the next generation. Mount Holyoke was the first seminary established exclusively for women, but it awarded only a certificate not a baccalaureate.

Emily Dickinson attended Mount Holyoke Female Seminary for two terms in 1847-48 but it was a mixed experience for her. For one thing, the curriculum repeated many of the texts and subjects Dickinson had studied at Amherst Academy, which she attended from 1840-47 and which was a more progressive institution that nurtured and even shaped her growing literary gifts. Dickinson was also extremely homesick and uncomfortable with the religious revival occurring at the time at Mount Holyoke, in which she was classified with several other girls as “a No-Hoper.”

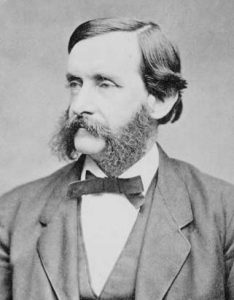

In her second letter to Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Dickinson answered what we can infer as his question about her education with this remark:

I went to school – but in your manner of the phrase – had no education (L261).

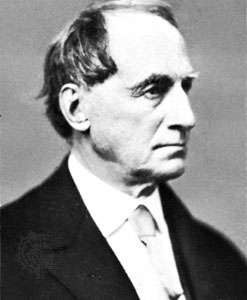

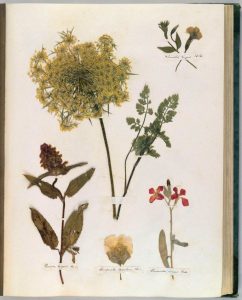

We have seen that Dickinson often minimized her situation to Higginson, in order to create the illusion of him as “Preceptor” and her as “scholar.” In fact, she had quite a good education at Amherst Academy, which Dickinson’s father Edward, her brother Austin, and Susan Gilbert attended, and whose curriculum, as well as the curriculum at Mount Holyoke Female Seminary, was shaped by Edward Hitchcock, the noted Professor of Geology and Theology and President of Amherst College (1845-54). This educational influence helps to explain the remarkable range of scientific knowledge, especially in botany, astronomy, and geology, in Dickinson’s writing. This week, we will look at the courses of study at the two institutions of learning Dickinson attended, the figures associated with them, and the effects of this education on her life and poetry.

“The Christian World is Indebted … Most of All to Mary Lyon”

Springfield Republican, July 26, 1862

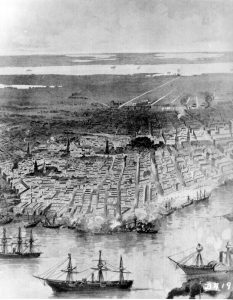

Progress of the War, page 1

“The prospect brightens, and popular confidence has been greatly reinforced by the appointment of general-in-chief [Halleck], virtually vacant since Gen. McClelland went into Virginia. He has command of all the land forces of the United States and will direct the general movements of the war.”

Foreign Affairs, page 1

“The new tariff, with its increased duties upon [British] goods, and the impediments placed in the way of trade, seems to have filled the cup of English bitterness to the brim.”

The Want of the Hour, page 2

“White men, we say, are the want of the hour, and white men must be our reliance. Is it to be so supposed that a negro will fight for his liberty more readily than a white man? Is it to be supposed that the poor African, after generating in bondage for centuries, will find in the prospect of liberty a greater incentive to fight for the suppression of the rebellion than the white man finds in the considerations that are thrust upon him? We have nationality at stake; we have our own political freedom at stake; we have personal and national honor at stake; we have the interests of republican liberty throughout the world at stake. The negroes of the South—‘our natural allies’—are unorganized, unarmed, ignorant and inaccessible.”

Poetry, Page 6

Books, Authors, and Art, page 7

“The time has gone by when cheap novels in paper covers could be safely thrown aside as the merest literary trash. We have now in this form the most unexceptionable fictions, correct, sensible and entertaining.”

Hampshire Gazette, July 29, 1862

Pleasant Neighbors, page 1

“One’s pleasure, after all, is much affected by the quality of one’s neighbors, even though one may not be on speaking terms with them. A pleasant, bright face at the window is surely better than a discontented, cross one; and a house that has the air of being inhabited is preferable to closed shutters and unsocial blinds, excluding every ray of sunlight and sympathy.”

Mount Holyoke Female Seminary, page 1

“For the foundation of institutions to give thorough intellectual training to women combined with the best religious influence, the Christian world is indebted to a very few persons, and most of all to Mary Lyon. At the time she instituted the seminary, there were in the country one hundred and twenty colleges for boys, but not one for girls, where they could get the highest form of education.”

“You are to Watch, and Water, and Nourish Plants”

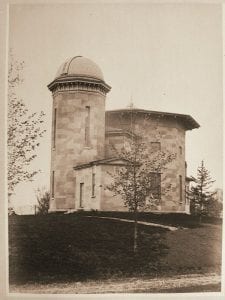

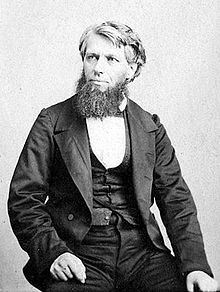

At age 5 Emily Dickinson attended the local “primary school.” From ages 9-16, she studied at the private Amherst Academy, a school her grandfather Samuel Fowler Dickinson helped found in 1814 to improve the level of education available in the area. The Academy was closely associated with Amherst College, employed many of its graduates as teachers and preceptors, and had a curriculum shaped by Edward Hitchcock, the inspirational man of science and religion who dominated the educational scene in Amherst and attracted many eminent scholars to the faculty of this small town in Western Massachusetts.

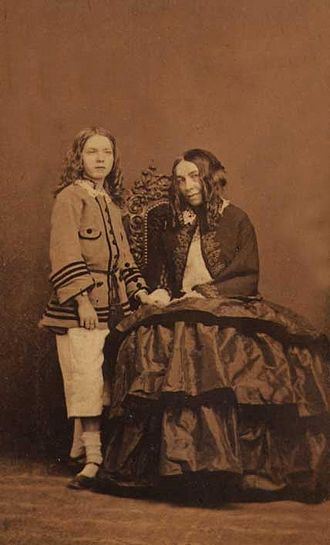

When Dickinson and Lavinia entered in Fall 1840, they joined a group of about 100 girls, supervised by a “preceptress,” who oversaw their academic as well as moral and religious development. Over her seven years’ attendance, Dickinson studied Latin, History, Ecclesiastical History, Botany, Mental Philosophy, Geology, Arithmetic, Algebra and Geometry, English, Rhetoric, Composition and Declamation.

Although most nineteenth-century education was based on rote learning, repetition, and an enforced distance between teacher and student, Amherst Academy was, by comparison (not current standards) a model of progressive thought. First, there was the influence of Edward Hitchcock, the eminent Professor of Geology and Theology at Amherst College, who emphasized the importance of the sciences, even for young students. Then, as Erika Scheurer argues,

the influence of Swiss education reformer Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi (1746-1827) and his disciples became more widespread, setting the stage for John Dewey’s more radical and celebrated reforms in the early twentieth century.

Pestalozzi and his New England followers, Samuel Read Hall and Richard Green Parker, stressed what Scheurer identifies as a “student-centered approach” that resembles the “liberation pedagogy” of Brazilian philosopher Paulo Freire. In this approach, students and teachers are encouraged to develop relationships of affection, not authority, learning is individualized and based on student autonomy and active agency.

Dickinson flourished in this environment in which Hall counseled young, well-educated teachers:

You are to watch, and water, and nourish plants.

Biographer Richard Sewall and Jack Capps, who has written an important study of “Emily Dickinson’s Reading,” discuss the beneficial effects of Amherst Academy’s progressive curriculum, especially in terms of Composition, on Dickinson’s development as a writer.

Schuerer explores this influence in detail, noting that Pestalozzi recommended “object teaching,” where “students learn to observe concrete objects from their lives, and then write about them in descriptive and analytical ways.” Hall encouraged ungraded informal personal writing and private letter writing, both of which Dickinson honed to a fine art. Parker took a “loose approach to questions of genre and form,” defining poetry by content (imagination and feelings) rather than form, embracing half-rhymes, the use of the dash as an expressive form of punctuation, and the use of capitalization to emphasize “[a]ny words when remarkably emphatical, or when they are the principal subject of the composition.” Dickinson clearly took these lessons to heart.

Although Mount Holyoke Female Seminary was a ground-breaking institution, it was a mixed experience for Dickinson academically and socially. She attended from September 30, 1847 to August 3, 1848, with several weeks at home in March and April with a bad cough. At the time of her enrollment, the Seminary had 235 students and 12 teachers. Mary Lyon encouraged a home-like atmosphere of cordiality between teachers and students, who all roomed together and did the household chores in a large brick house that combined living and academic spaces.

Still, the Seminary was bound by 70 rules for living, learning, and visiting, including an injunction to turn in rule-breakers. The day began at 6 am and was divided into half hour segments closely scheduled with times for academic studies, private meditation, prayer, calisthenics, chores and meetings. Dickinson chafed against the lack of privacy, lack of connection to the outside world and current affairs (she wrote a letter to her brother Austin jokingly asking: Who are the presidential candidates and is the Mexican War over?), the repetition of textbooks and subjects she studied at Amherst Academy, and the limited opportunities to visit her family just nine miles away.

And then there was the religious revival that started in December 1847 and lasted until May 1848. Biographer Alfred Habegger narrates the details of the “well-coordinated campaign” for Dickinson’s soul, and though Dickinson seems to have resisted in a particularly noteworthy way, at the end of the year, 30 of the 235 students at the Seminary were also “No-Hopers.” This failure left Mary Lyon sick and depressed, and she died seven months later at age 52, at the height of her career.

From a poor background, Lyon used the meager schooling and connections available to her to become an expert in women’s education and the founder of Mount Holyoke Female Seminary, where she taught Chemistry and often cooked for the school. A student of Edward Hitchcock’s, she shared his passionate commitment to evangelical Christianity. Although she told young women they could do anything and opened her Seminary to the young working women from the Lowell Mills, the mission of her school was to produce women who would become devout wives and mothers and spread the word of Christ. Habegger notes with some irony that during Dickinson’s summer term at Mount Holyoke, on July 19-20, 1848, a small convention took place in Seneca Falls, New York, kicking off the “first wave” of women’s rights. But that seemed worlds away from South Hadley.

Reflection

Tom Luxon

I am intrigued by Erika Scheurer’s description of the educational philosophy that underpinned the curriculum at the Amherst Academy Emily Dickinson attended from 1840 to 1847. Scheurer describes it as a “student-centered approach” to education that anticipated Dewey and even Paulo Freire’s liberation pedagogy. “Teachers and students,” she writes, “are encouraged to develop relationships of affection, not authority, learning is individualized and based on student autonomy and active agency.” Based on my more than thirty years in higher education, including nine years as the founding director of a teaching and learning center, I consider the Academy’s practice progressive even by today’s standards. Today, lectures, quizzes, and exams still dominate the practice of teaching in higher education. Students no longer copy notes with slate and pencil, but power-point presentations are just as teacher-centered and content-centered as the typical 19th-century classroom. Learner-centered education has long been recommended by education experts and researchers, but largely ignored in US colleges and universities.

I am intrigued by Erika Scheurer’s description of the educational philosophy that underpinned the curriculum at the Amherst Academy Emily Dickinson attended from 1840 to 1847. Scheurer describes it as a “student-centered approach” to education that anticipated Dewey and even Paulo Freire’s liberation pedagogy. “Teachers and students,” she writes, “are encouraged to develop relationships of affection, not authority, learning is individualized and based on student autonomy and active agency.” Based on my more than thirty years in higher education, including nine years as the founding director of a teaching and learning center, I consider the Academy’s practice progressive even by today’s standards. Today, lectures, quizzes, and exams still dominate the practice of teaching in higher education. Students no longer copy notes with slate and pencil, but power-point presentations are just as teacher-centered and content-centered as the typical 19th-century classroom. Learner-centered education has long been recommended by education experts and researchers, but largely ignored in US colleges and universities.

I can just imagine Pestalozzi, Hall, and Parker running exciting workshops at the Dartmouth Center for the Advancement of Learning, championing “object teaching” and ungraded analytical essays. The dozen or so participants would listen with fascination; half of them would try to adopt such methods; half of those would stick with it. But the teaching awards and major institutional recognition would continue to reward the clever lecturer and his power-point slides.

bio: In teaching and scholarship, I have focused on literature of the English Renaissance and Reformation, with a particular interest in John Milton, John Bunyan, John Dryden, and 17th-century English religion and politics. I am keenly interested in technological innovations for teaching and learning. I served from 2004 to 2013 as the inaugural Cheheyl Professor and director of the Dartmouth Center for the Advancement of Learning. For more, see my website.

See my most recent articles: from Milton Studies, volume 59: “Heroic Restorations: Dryden and Milton,”

and in Queer Milton, edited by David L. Orvis:

https://www.palgrave.com/us/book/9783319970486

Sources:

History

Hampshire Gazette, June 17, 1862.

Springfield Republican, July 29, 1862

Biography

Capps, Jack L. Emily Dickinson’s Reading: 1836-1886. Cambridge: Harvard University, 1966, 15-26. See Appendix B for a list of Dickinson’s Mount Holyoke textbooks.

Habegger, Alfred. My Wars are Laid away in Books. New York: Random House, 2001, 139-66, 191-212.

Porter, Amanda. Mary Lyon and the Mount Holyoke Missionaries. Religion in America Series. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Scheurer, Erika. “‘[S]o of course there was Speaking and Composition –’: Dickinson’s Early Schooling as a Writer.” The Emily Dickinson Journal 18, 1 (2009): 1-21, 3-4, 6-7, 11-18.

Sewall, Richard. The Life of Emily Dickinson. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1980, 337-57.