On Choosing the Poems on Choosing

As we said in the Overview of this week’s post, we curated our gathering of poems around “The Soul selects her own Society,” a touchstone poem about selection and choosing in Dickinson’s canon. We also mentioned that Dickinson’s first editors, Mabel Loomis Todd and Thomas Wentworth Higginson, included this poem in the first published edition of Dickinson’s poetry in 1890 under the title “Exclusion.” Helen Vendler concludes her insightful reading of the poem with this fact and asks pointedly:

As we said in the Overview of this week’s post, we curated our gathering of poems around “The Soul selects her own Society,” a touchstone poem about selection and choosing in Dickinson’s canon. We also mentioned that Dickinson’s first editors, Mabel Loomis Todd and Thomas Wentworth Higginson, included this poem in the first published edition of Dickinson’s poetry in 1890 under the title “Exclusion.” Helen Vendler concludes her insightful reading of the poem with this fact and asks pointedly:

Was “Selection” too peremptory a word for a female to use at the time?

We think perhaps it was, and yet, “select” is the word Dickinson uses for what Vendler calls the soul’s “absolute choice.”

What accounts for Dickinson’s preoccupation with choice and selection at this time? Is it a celebration of “the will to choose” or the fear of exposure? Or some combination? We know Dickinson suffered a great loss in 1861, which might have been a rejection of love, and she began withdrawing into the Homestead and into her corner room. One of her biographers, Alfred Habegger, associates the stringent selection presented in “The Soul selects her own Society” with Dickinson’s rejection of Samuel Bowles, whom, at this point, Habegger said,

no longer had the key to Dickinson’s attention.

As Habegger reconstructs the story, Dickinson sent Bowles “Title divine – is mine!,” which she regarded as a confession of sorts, and insisted on complete confidentiality. But when Bowles visited Amherst in November 1862, Dickinson refused to see him and Bowles dashed off a note to Austin Dickinson, with whom he was very close, calling Dickinson “the Queen Recluse” and referring to her “Maidens vows.” This got back to Dickinson, who felt Bowles had violated her trust, and he would be from then on exiled from her intimacy. Habegger observes:

Because of the misdating of key documents, it hasn’t been understood that between late 1862 and 1874 she sent him no personal letters and few poems. … the relationship had been irreparably damaged.

Of all the Souls that stand create (F279, J664)

Of all the Souls

that stand create –

I have Elected – One –

When Sense from Spirit –

files away –

And Subterfuge – is done –

When that which is –

and that which was –

Apart – intrinsic – stand –

And this brief Tragedy

of Flesh –

Is shifted – like a Sand –

When Figures show their

royal Front –

And Mists – are carved away,

Behold the Atom – I pre –

ferred –

To all the lists of

Clay!

EDA manuscript: “Originally in Amherst Manuscript # 304, asc:11377 – p. 1. Courtesy of Amherst College Library, Amherst, MA. First published in Poems (1891), 89, as three quatrains, with the alternative adopted.”

We begin with this poem because it so clearly uses the language of Protestant “election,” the doctrine that teaches that at the beginning of the world God selected or predestined certain souls to be saved and join him in Heaven for all eternity and others to be damned and suffer in hell. Dickinson adapts this belief to the speaker’s choice of a beloved. In this adaptation, the speaker somewhat arrogantly takes the place of God, when in the penultimate line the speaker says, “Behold the Atom – I preferred.” It is hard not to hear “Adam,” as if God had just created man from the dust (“Clay”) and presented him to the Heavenly Host for their admiration. This line also evokes the phrase “Ecce homo,” Latin for “behold the man,” the words Pontius Pilate spoke as he presented a defeated Jesus, bound and crowned in thorns, to a hostile crowd just before his crucifixion (see John 19:5).

He is a man, not God, is Pilate’s sneering implication, but Dickinson sets her poem at the moment when the body transforms into the soul, when the mists of flesh recede and “Figures” are revealed as “royal.” Despite the joy in this poem, exercising choice seems, for Dickinson, to be bound up with a suffering so extreme, she can only express it in terms of the Crucifixion.

Formal aspects of this poem contribute to the complexity of choosing. The rhythm of the common meter, alternating four and three feet lines rhyming abcb, is largely iambic (that is, feet of unstressed and Stressed syllables) except for line 2. There, we can impose the sing-song rhythm with a stress on “have,” but the words force us to read this as a trochee (Stressed/unstressed), stressing “I,” the doer of the action, the agent, thus emphasizing the importance of this act.

Other notable elements are Dickinson’s arresting diction in the phrase “stand create,” the use of the verb phrase “files away” for the separation of body and soul (with its shadow echo of “flies away”), the singular “a Sand” for what is myriad (compare to “a Hay” in “The Grass so little has to do”(F379). This anticipates the image of “the Atom” as a way of describing the chosen one, a word stripped of gender, identity and multiplicity—the person reduced to his/her/their most elemental. Also, the variant “Drama in the flesh” for “Tragedy of Flesh,” which Dickinson writes directly above the phrase rather than at the end of the poem, as usual, evokes Dickinson’s beloved Shakespeare.

There are some fascinating readings of this poem. Richard Wilbur argues that

the beloved’s lineaments, which were never very distinct, vanish entirely; he becomes pure emblem, a symbol of remote spiritual joy, and so is all but absorbed into the idea of Heaven.

Helen Vendler reads this as an apocalyptic poem about the Last Judgment, and Mary Loeffelholz understands it as one of many love poems Dickinson wrote using as its model

Christianity’s sacred narrative of incarnation, passion, and redemption.

Sources

Loeffelholz, Mary. The Value of Emily Dickinson. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016, 37-71.

Vendler, Helen. Dickinson: Selected Poems and Commentaries. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University, 2010, 98-100.

Wilbur, Richard. “Sumptuous Destitution.” The Networked Wilderness: The Connected World of Emily Dickinson. Amherst College Press, 2017, 113-122.

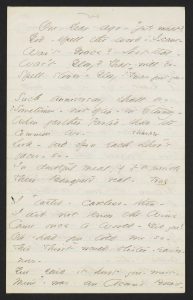

One Year ago–Jots what (F 301A, J 296)

One Year ago – jots what?

God – spell the word! I – cant –

Was’t Grace? Not that –

Was’t Glory? +That – will do – + ‘Twas just you –

Spell slower – Glory –

Such anniversary shall be –

Sometimes – not often – in Eternity –

When +farther Parted, than the + sharper

common Wo –

Look – feed opon each other’s

faces – so –

In doubtful meal, if it be possible

Their Banquet’s +real – +True

I tasted – careless – then –

I did not know the Wine

Came once a World – Did you?

Oh, had you told me so –

This Thirst would blister – easier –

now –

You said it hurt you – most –

Mine – was an Acorn’s Breast –

And could not know how

fondness grew

In Shaggier Vest –

Perhaps – I could’nt –

But, had you looked in –

A Giant – eye to eye with

you, had been –

No Acorn – then –

So – Twelve months ago –

We breathed –

Then +dropped the Air – +lost

Which bore it best?

Was this – the patientest –

Because it was a Child,

you know –

And could not value – Air?

If to be “Elder” – mean most pain –

I’m old enough, today, I’m

certain – then –

As old as thee – how soon?

One – Birthday more – or Ten?

Let me – choose!

Ah, Sir, None!

EDA manuscript: “Originally in Fascicle 12 (H112), early 1862. First published in Bolts of Melody (1945), 159-60, as seven stanzas of 5, 6, 5, 4, 4, 7, and 6 lines. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.”

This “anniversary” poem notes the passing of a year since some momentous event in the speaker’s life involving a lover, possibly male, since he has a “Shaggier Vest,” that is, a hairy chest unlike the speaker, who contrasts this to her “Acorn’s Breast,” round, smooth, brown and definitely not hairy!

This poem is notable for its headlong and varied pace and its lack of metrical consistency, an example of Dickinson’s free verse. As the emotions and metaphors shift, so do the line lengths. Stanza one bumps along, interrupted by spondees (feet of two Stressed syllables): “jots what?” “I – can’t,” “Not that,” “will do.” In stanza two, the metaphor of a banquet for the lovers looking and feeding “opon each other’s faces – so –” expands into longer pentameter lines of five feet to suggest the bounty of this feast, which also echoes the spiritual plenty of the communion meal and the sacramental wine they drink in stanza three. The poem never really settles rhythmically, and the final two lines clinch the formal sense of truncation.

This poem is notable for its headlong and varied pace and its lack of metrical consistency, an example of Dickinson’s free verse. As the emotions and metaphors shift, so do the line lengths. Stanza one bumps along, interrupted by spondees (feet of two Stressed syllables): “jots what?” “I – can’t,” “Not that,” “will do.” In stanza two, the metaphor of a banquet for the lovers looking and feeding “opon each other’s faces – so –” expands into longer pentameter lines of five feet to suggest the bounty of this feast, which also echoes the spiritual plenty of the communion meal and the sacramental wine they drink in stanza three. The poem never really settles rhythmically, and the final two lines clinch the formal sense of truncation.

The allusion to choice comes at the end of the poem but is enigmatic (and, perhaps, generalizable) in its reference. The speaker notes the pain both parties have suffered, and says, “If to be ‘Elder’ – mean most pain –/ I’m old enough today.” But she wants to be as old as the beloved (to equalize the pain) and wonders “how soon?” trying to guess the number of birthdays this would require. She concludes: “Let me – choose!/ Ah, Sir, None!”

Is she saying, no more birthdays, no more passage of time, no more separation or pain—that is what I would choose? Or does this preference for choosing “none” also encompass the whole scenario of the original choice of the beloved, the one “Atom” selected “from all the lists of Clay”? It should not escape notice that these lines resolutely confirm Sharon Cameron’s finding, from reading the fascicles, that Dickinson’s method can be best characterized as “choosing not choosing,” which is slightly different from choosing “none.” But both carry the sense of Dickinson’s radical refusing of closure and determinacy, her desire to dwell in the openness of possibility.

Sources

Cameron, Sharon. Choosing Not Choosing: Dickinson’s Fascicles. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992.

Kornfeld, Susan. “One Year ago– jots what?” the prowling bee: blogging all the poems of Emily Dickinson. 25 July, 2012.

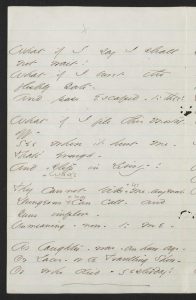

What if I say / I shall not wait (F305, J277)

What if I say I shall

not wait!

What if I burst the

fleshly Gate –

And pass Escaped – to thee!

What if I file this mortal –

off –

See where it hurt me –

That’s enough –

And +step in Liberty! +wade

They cannot take +us – any more! +me

Dungeons +may call – and +can

Guns implore –

Unmeaning – now – to me –

As laughter – was – an hour ago –

Or Laces – or a Travelling Show –

Or who died – yesterday!

EDA manuscript: “Originally in Packet XIV, Mixed Fasciles, ca. 1860-1862. First published in Poems (1891), 107, as two six-line stanzas, with the alternatives adopted. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.”

Readers view this poem as referring to suicide, which can be understood as the ultimate choice, choosing to live or not, a human rebellion against the dictates of God and Nature. Certainly, the word “file” in line 4 echoes Dickinson’s use of it in “Of all the souls that stand create” and connects these poems: “When Sense from Spirit – / files away.” Here, though, it has an identifiable subject: “What if I file this mortal off,” which suggests direct agency and deliberation, if not gruesome self-harm.

This poem is unusual because Dickinson almost always prefers the present earthly life to the future Heavenly one, sometimes to the point of blasphemy. Yet here, the speaker wonders whether to “file this mortal off” will produce the desired “Liberty” in a condition in which life is associated with “dungeons” and “guns imploring” (by being held at gunpoint?), with “Laces” that constrain (suggesting women’s corsets and fitted clothing), with the illusions of a “Travelling Show.”

The poem has been copied in ink, but variants were written, presumably at a later time, in pencil, suggesting that Dickinson came back to this poem. In line six, the variant for “step” changes the phrase to “wade in Liberty,” intensifying the fantasy of death as release, and echoing another poem from this period, “I can wade Grief – Whole Pools of it” (F312A, J252). In line seven, the variant for “me” is “us,” so that “They cannot take us – any more!” is not just about the speaker but a companion or lover, or the reader, who are also repressed and captivated. At least they/we are together.

The tenses and temporality are also telling. The poem begins in speculation: “What if” repeated three times. In the third stanza, it’s as if this vision has come to pass and the speaker is not just imagining being beyond capture or harm, but has achieved it. William Shurr argues:

It takes a rather unimaginative seriousness to read this poem, so full of wit and hyperbole, as a suicidal threat. It is a lover’s mock protest, rather, addressed to her beloved “thee.”

Certainly, there is irony in the last line: once I am dead or free, the knowledge of “who died – yesterday” will be meaningless to me. But with that also goes “laughter.”

Sources

Shurr, William. The Marriage of Emily Dickinson: A Study of the Fascicles. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1983, 40, 84.

Tie the strings to my life (F338, J279)

[No image of ms. is available]

Tie the strings to my Life,

My Lord,

Then, I am ready to go!

Just a look at the Horses –

Rapid! That will do!

Put me in on the firmest

side –

So I shall never fall –

For we must ride to the

Judgment –

+ And it’s partly, down Hill – +And it’s many a mile –

But never I mind the +steepest – +Bridges

And never I mind the Sea –

Held fast in Everlasting Race –

By my own Choice, and Thee –

Good bye to the Life I used to live –

And the World I used to know –

+And kiss the Hills, for me, just once – +Here’s a keepsake for the Hills

+ Then – I am ready to go! +Now

EDA manuscript: “Originally in Fascicle 16 (H 53), summer 1862. First published in Poems (1896), 174, with the alternatives for lines 9 and 16 adopted. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.”

Another ride in a carriage, this time with “My Lord,” an ambiguous referent, to “the Judgment,” which the speaker quips, is “partly, down Hill,” suggesting they are descending (morally or spiritually) rather than ascending up to Heaven. This allegorical scene can mean many things. The speaker claims that despite challenges posed by the “steepest” places and by the Sea (which is a threat in many poems, symbolizing erotic desire; see “I started Early – took my dog” F656, J520), she is “Held fast … By my own Choice, and Thee.”

The stabilizing force of choice is not without qualification. Whoever “thee” is, whether God or a beloved, or some kind of Master, this force is necessary to hold the speaker to this journey. This echoes the speaker’s awareness of the qualified nature of choice in the first lines: “Tie the strings to my Life, My Lord.” She commands him, exercising will, but what she commands is that strings be tied to her life to secure it, bind it, complete it. How close is this to the acceptance of selection and subjection in “He put the Belt around my life” (F330A, J273)?

William Shurr reads the poem as mirroring

not a death wish but another … version of [the lovers’] acknowledgement of their oneness, their certain union in heaven and their secure feelings towards Judgment because of their sacrifice.

Maryanne Garbowsky reads the poem as about

a death to a way of life, rather than an actual death.

And Virginia Oliver counters that the very security and lack of doubt Shurr celebrates and

found in many other Dickinson poems on the subject makes one wonder … if she might be trying to convince herself rather than expressing firmly held convictions.

Sources

Garbowsky, Maryanne M. “A Maternal Muse for Emily Dickinson.” Dickinson Studies 41 (Dec. 1981): 12-17.

Oliver, Virginia. Apocalypse of Green: A Study of Emily Dickinson’s Eschatology. American University Studies. Series 24: American Literature 4. New York: Lang, 1989, 149-50.

Shurr, William. The Marriage of Emily Dickinson: A Study of the Fascicles. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1983, 40.

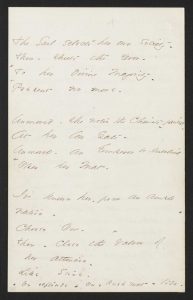

The Soul selects her own Society (F409)

The Soul selects her own Society –

Then – shuts the Door –

To her divine Majority –

+Present no more – +Obtrude

Unmoved – she notes the Chariots – pausing –

At her low Gate –

Unmoved – an Emperor be kneeling

+ Opon her Mat – +On [her] Rush mat

I’ve known her – from an ample

nation –

Choose One –

Then – close the – +Valves of +lids

her attention –

Like Stone –

EDA manuscript: “Originally in Packet XIII, Mixed Fasciles, ca. 1862. First published in Poems (1890), 26, from the fascicle copy (A), with the alternatives for lines 3 and 4 adopted. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.”

This is a touchstone poem about selection and choice in Dickinson’s canon and it has been much read and much debated. Helen Vendler does a close reading of the poem, comparing it to “Of all the Souls that stand Create” (F 279), which, she argues, recounts in “unsurpassable” terms the soul’s “eschatological” or timeless and eternal choice of one person. Here, she thinks, Dickinson redoes the topic “in humbler terms.”

One place to start is with the form. Each stanza begins with long lines followed by very short ones, which sets a pattern of extension and truncation that feels like something being shut down or out. The first two stanzas begin with pentameter lines followed by short lines of dimeter (two feet each). The third stanza starts with a nine syllable line followed by a monometer (one foot line). Attention is getting shorter and shorter. In this last stanza, the monometer lines contains spondees, two stressed syllables that bang shut with a double thump. Annie Finch observes that the poem

retreats from its initial iambic pentameter line, a movement that metrically parallels the poem’s verbal description of self-reliance and frugality.

The word “valves” with its variant of “lids” suggests an exclusion that resembles blindness and suffocation. The final rhyme of “One” and “Stone” reinforces the sense of rigidity, especially in how the first word is enclosed in the second.

In reading this poem, many readers invoke Emerson’s Transcendental notion of self-reliance and his advocacy of retreating into the soul in search of the divine. Emily Budick suggests the poem

borrows linguistic trappings from Puritan theology and applies them to the phenomenon of Transcendentalism.

Notable is the theme of royalty in the “Chariots” that pause at the soul’s humble abode, and the “Emperor” found kneeling upon the soul’s lowly door mat. It is also important to note that in the third stanza, the speaker differentiates herself from this discerning “soul,” or speaks about herself in the third person–how discriminating!

Sources

Budick, E. Miller. “When the Soul Selects: Emily Dickinson’s Attack on New England Symbolism.” American Literature 51.3 (Nov. 1979): 349-63, 352.

Finch, A. R. C. “Dickinson and Patriarchal Meter: A Theory of Metrical Codes.” PMLA 102.2 (Mar. 1987): 166-76, 172-3.

Vendler, Helen. Dickinson: Selected Poems and Commentaries. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University, 2010, 187-190.

More life – went out (F415A, J422)

More Life – went out – when

He went

Than Ordinary Breath –

Lit with a finer Phosphor –

Requiring in the Quench –

A Power of Renowned Cold,

The Climate of the Grave

A Temperature just adequate

So Anthracite, to live –

For some – an Ampler Zero –

A Frost more needle keen

Is nescessary, to reduce

The Ethiop within.

Others – extinguish easier –

A Gnat’s minutest Fan

Sufficient to obliterate

A Tract of Citizen –

Whose Peat life – amply

vivid –

Ignores the solemn News

That Popocatapel exists –

Or Etna’s Scarlets, Choose –

EDA manuscript: “Originally in Packet X, in Fascicle 14 (H 48), ca. 1862. First published in Yale Review, 25 (Autumn 1935), 76, and Unpublished Poems (1935), 4, the first four stanzas. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.”

In this riddling poem that uses imagery of heat and frost, we learn at the end that what “chooses,” or perhaps, the effects of choosing, are like erupting volcanoes: “Etna,” an active volcano on the Italian island of Sicily; and Popocatapel, a volcano in central Mexico, described in Dickinson’s Webster’s as

a towering volatile peak; mountain capable of erupting in spectacular flames and lava flows.

This imagery connects the effects of choosing with the pressurized, subterranean and spectacular power of volcanoes, a theme threaded throughout Dickinson’s work. Volcanoes are both deadly, as in the case of Vesuvius destroying the city of Pompeii, and generative as a figure for the female poet who has to look “still” but is roiling with creative force underneath, as in this commanding poem from 1863:

A still – Volcano – Life –

That flickered in the night –

When it was dark enough

to show do

Without endangering erasing sight –A quiet – Earthquake style –

Too +subtle to suspect +smouldering

By natures this side Naples –

The North cannot detectThe solemn – Torrid – Symbol –

The lips that never lie –

Whose hissing Corals part – and shut –

And Cities – +ooze away – (F517A, J601). +– slip – • slide – • melt

In “More Life – went out” the speaker characterizes the extraordinary life she admires in terms of different kinds of heat, and how that heat might be “quenched.” This life was “lit with a finer Phosphor;” according to Dickinson's Webster’s, this is “a substance that shines in the dark; [fig.] vitality; vivacity; energy; spark of life.” Anthracite is a “species of coal which has a shining luster, approaching to metallic, and which burns without smoke, and with intense heat.” The EDA notes:

The meaning of “Anthracite’” (line 8) may derive from a distinction in Reveries of a Bachelor (1850) by Donald Grant Mitchell (“Ik Marvell”) between “bituminous” and “anthracite” people, the latter characterized by a steady, profound sensibility not easily quenched.

Anthracite, contrasted with “Peat,” is defined as

Organic; humus-like; sod-like; like dry soil; made of earthly elements; [fig.] dull; colorless; drab; plain; dreary; lackluster; humble; ordinary; human; mortal.

Thus, a “peat life” is unremarkable.

Dickinson also connects the extraordinary life with the warmer zones, the equator, and with the “Ethiop within,” a figure of color we have met in another guise in “The Malay took the Pearl,” and who often stands as a figure for energy, passion, life force and (masculine) power.

Sources

Hallen, Cynthia, ed. Emily Dickinson Lexicon. Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University, 2007.

Sources

Habegger, Alfred. My Wars are Laid Away in Books. New York: Random House, 2001, 446-51.

Vendler, Helen. Dickinson: Selected Poems and Commentaries. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University, 2010, 190.