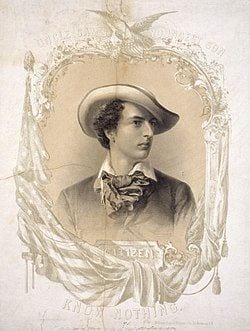

This week in 1862 the Springfield Republican published an article under the eye-catching title “Immigration to Be Encouraged.” This fact was rather surprising in a largely homogenous white and Protestant nation, which experienced anti-immigrant riots in the 1840s and 1850s, as well as the rise of the Know-Nothing Party, whose dominant issue was restricting immigration. But apparently, according to the Republican,

almost every farming town, and especially in the West, has exhausted all its available labor and the cry is for more men to cultivate the fields.

Given our present-day conflicts about immigration and the ongoing tragedy of separating immigrant parents and children, we decided to focus this week on the image of “home” in Dickinson’s life, thinking and writing, and what it means to be or feel at home and/or homeless.

Several prominent literary scholars and psychologists—Gaston Bachelard, Kenneth Burke, Sigmund Freud and Erik Erikson to name a few—have explored what Jean McClure Mudge calls “the reverberatory power of this central symbol” of home in our culture and literature. For psychologist Erikson,

the optimum sense of identity is to possess a feeling of at homeness.

In 1975, Mudge applied some of these writers' insights to Dickinson’s extensive use of this image and found that it

is perhaps the most penetrating and comprehensive figure she employs, [emerging] as a unique and unifying touchstone to several facets of the poet’s consciousness.

Mudge also sees a “universality” in Dickinson’s

situation, which was sometimes, if not gnawingly, to feel out-of-place as woman and writer, in short, homeless.

Sill, Mudge notes how frequently other writers of the time—Nathaniel Hawthorne and Herman Melville, for example—expressed a similar feeling, and how “it seems to be the hallmark of our own day.” By exploring Dickinson’s many homes and houses—of nature, the body, the mind, poetry, memory, God—and their layered associations, we might illuminate our own fraught experiences of home and away.

“Praesidium et Dulce Decus”

Springfield Republican, August 30, 2018

Progress of the War, page 1

“The withdrawal of Gen. McClellan’s army from the James [River], while our army in eastern Virginia was on the banks of the Rapids involved great and obvious hazards. It gave the rebel leaders the best opportunity they could desire to throw their entire force against the smallest division of our army and annihilate before the army from the James could arrive to the rescue, and they were not slow to see and to seize their opportunity. But this had been foreseen and provided against as fully as could be. Gen. Pope made a quick and unmolested retreat from the Rapids to the Rappahannock, where he could make a better defense against the vastly superior numbers.”

Immigration to Be Encouraged, page 2

“The recent letter of Secretary Seward addressed to J.N. Gamble of Cincinnati, in which the subject of aid in our farming and industrial pursuits from foreign laborers is presented, is the key-note to a matter of vast and growing importance in our country, especially the West. The letter was in reply to a suggestion of Mr. Gamble that special efforts should be made to make up for a deficiency in laborers by encouraging immigration. We are glad that the foresight of our secretary anticipated the need, for almost every farming town, and especially in the West, has exhausted all its available labor and the cry is for more men to cultivate the fields.”

Feminine Advisers, page 6

“It is a wonderful advantage to a man, in every pursuit or avocation, to secure an adviser in a sensible woman. In woman there is at once a subtle delicacy of tact, and a plain soundness of judgment, which are rarely combined to an equal degree in man. A woman, if she really be your friend, will have a sensitive regard for your character, honor, repute. Female friendship is to man, ‘praesidium et dulce decus’—bulwark, sweetener, ornament of his existence. To his mental culture it is invaluable; without it all his knowledge of books will never give him knowledge of the world.”

Hampshire Gazette, September 2, 1862

Curious Case of Superstition, page 1

“A widow lady in Paris, aged about sixty-three, was accustomed to spend several hours every day before the altar dedicated to St. Paul in a neighboring church. Some villains, observing her extreme weakness, resolved, as she was known to be very rich, to share her wealth. One of them accordingly concealed himself between the carved work of the altar, and when no person but the old lady was there, he contrived to throw a letter right before her. She took it up, supposing it to be a miracle. In this she was more confirmed when she saw it signed ‘Paul, the Apostle,’ expressing the satisfaction he received by her prayers addressed to him, when so many newly canonized saints engrossed the devotion of the world and robbed the primitive saints of their wonted adoration.”

A Nice Girl, page 1

“There is nothing half so sweet in life, half so beautiful, or delightful, or so lovable as a ‘nice girl.’ Not a pretty, or a dashing, or an elegant girl, but a nice girl. One of those lovely, lively, good-tempered, good-hearted, sweet-faced, amiable, neat, natty, domestic creatures met within the sphere of home, diffusing around the domestic hearth the influence of her goodness, like the essence of sweet flowers.”

Atlantic Monthly, August 1862

The New Gymnastics, page 129 by Dr. Dio Lewis (1823-1886)

“The common remark, that parents are too much absorbed in the accomplishments of their daughters to give any attention to their health, is absurd. Mothers know that the happiness of their girls, as well as the character of their settlement in life turns more upon health and exuberance of spirits than upon French and music. To suppose that, while thousands are freely given for their accomplishments, hundreds would be refused for bodily health and bloom, is to doubt the parents’ sanity.

“Home, Sweet Home!”

Of all the poets in an age that idealized home and associated women with domestic space, Dickinson is probably the one most closely associated with a house and home. Given that at some point in the 1860s, she started not leaving the Homestead, the gracious house her grandfather built and her father expanded and moved the family back into in 1855 after being forced to leave for a humiliating period of fifteen years. “Home” was a pervasive cultural icon of this period of growing industrialization and civil conflict. So redolent of peace and security that, according to Patrick Browne, popular songs like “Home, Sweet Home!” were banned in the Union Army camps because they incited desertions. To this day, and thanks to the loving curation of the Homestead’s buildings and grounds (pictured above), Dickinson is closely associated with this place, the literal house where she wrote all but a few of her early poems and many of her letters.

Of all the poets in an age that idealized home and associated women with domestic space, Dickinson is probably the one most closely associated with a house and home. Given that at some point in the 1860s, she started not leaving the Homestead, the gracious house her grandfather built and her father expanded and moved the family back into in 1855 after being forced to leave for a humiliating period of fifteen years. “Home” was a pervasive cultural icon of this period of growing industrialization and civil conflict. So redolent of peace and security that, according to Patrick Browne, popular songs like “Home, Sweet Home!” were banned in the Union Army camps because they incited desertions. To this day, and thanks to the loving curation of the Homestead’s buildings and grounds (pictured above), Dickinson is closely associated with this place, the literal house where she wrote all but a few of her early poems and many of her letters.

But “home” was also a fraught space for Dickinson. She mentioned “emigrant” twice in her letters, both times in relation to the Homestead, suggesting that she experienced being a kind of immigrant in her home. In a letter to her dear friend Elizabeth Holland written in January 1856, Dickinson describes the move from the family’s Pleasant Street home to the Homestead, all of a block and a half away, in humorous terms with a cutting edge:

It is a kind of gone-to-Kansas feeling, and if I sat in a long wagon, with my family tied behind, I should suppose without doubt I was a party of emigrants!

They say that “home is where the heart is.” I think it is where the house is, and the adjacent buildings (L 182).

According to Patricia Thompson-Rizzo, who does a thorough reading of this complicated letter, Dickinson may be alluding to the sentiments if not the words of John Greenleaf Whittier's 1854 poem, "Song of the Kansas Emigrants,” which also contains the resonant term “Homestead:”

We cross the prairies, as of old

Our fathers crossed the sea;

To make the West as they the East

The Homestead of the Free.

At the time of this move, Dickinson’s father Edward was a congressman and proponent of the idea of manifest destiny embodied in the immigration to Kansas, also known as “Bloody Kansas,” the site of bitter controversy and strife over the legality of slavery. Thompson-Rizzo concludes:

Reluctantly dragged to the neoclassically refurbished Homestead, Dickinson exposes the myth [of manifest destiny] so keenly lived by her father, [thus] providing an overt, albeit imaginative critique of the expansionist aims underlying the cult of domesticity as recently deconstructed by Amy Kaplan.

The second mention of emigrants comes in a June 1869 letter to Thomas Wentworth Higginson:

You noticed my dwelling alone -To an Emigrant, Country is idle except it be his own (L330).

Dickinson did not dwell “alone,” but was very much a part of her family's life. In some ways, though, Dickinson still felt like an immigrant in her father’s house or, at least, wanted Higginson to believe so. She recognized and sympathized with the emigrant’s sense of loss and “idleness” in a strange land.

Over her life, Dickinson made many more striking assertions about her home and the concept of home especially in her letters. For example, in 1851 she wrote to her brother Austin, away at school, about the Dickinsons’ second home on Pleasant Street (which was later razed): “Home is a holy thing” (L59). In 1870, she wrote to a friend congratulating him on his marriage, saying: “Home is the definition of God” (L355). In 1875, she wrote to Maria Whitney: “Consciousness is the only home of which we now know. That sunny adverb had been enough were it not foreclosed” (L591). As Jean Mudge remarks, enclosures like houses and bodies and coffins were never far in Dickinson’s world from “closures,” endings, separations, death. Perhaps most famously, in 1876, Dickinson sent this resonant declaration to Thomas Higginson:

Nature is a Haunted House – but Art – a House that tries to be haunted (L459a).

Homes and houses abound in the poetry as well. One of Dickinson’s speakers declares, “I dwell in Possibility – / A fairer House than Prose –” (F466A, J657) and another tells how she is exploring “Vesuvius at Home” (F1691A, J1705).

Scholars who work on Dickinson’s images of home and houses approach them from different directions: as an index of her attitude towards space and her body; as forms of containment; as structuring images; as “a sheltering framework;” as a metaphor for “breaking down the boundaries of consciousness.” All link her physical experiences of houses with her metaphysical concerns, which raises her poetry of domestic space to existential heights. As J. Brooks Bouson explains it, the house image

explores her Chinese-box view of reality: the soul or the mind of the poet is in the body which dwells in a house (in Amherst). That house, in turn, is contiguous to nature's house which borders on the heavenly home. Her special complication in considering this topic is that Dickinson uses the image in a paradoxical sense: that which is finite is replete with the infinite.

This is what Dickinson calls her “Compound Vision -/ Light enabling Light – The Finite furnished with the Infinite” (F830A, J906). Exploring these boundaries, according to Bouson, Dickinson “is paradoxically both released and confined in safety or as a prisoner.” The downside to this is that she can never achieve a resolution or synthesis

but only unresolved paradox as she uses her art to define the space she occupies and to bring into focus different planes of reality which are simultaneously remote and near.

Reflection

Eliot Cardinaux

Passing, Exaltation, Pastorale

I

That wood in the wind clatters

slowly as laughter yawns

in the belly of weeping,

that the pain splits the earth

in her laughing,

the same two masks

which pale as noon marble

into sunset, crowding

the dome with shadow,

that heap in her folds,

to measure like wings, and

swallow a dream between.

II

On nature a dying love is placed;

she melts over the pines,

her shadow waxen.

An emblem of guilt

we embrace,

he invented the mind.

Like sinew, her wings’ acting

comfort the will

demands graces,

like thistle below a sign,

somewhere an action

we keep still.

III

Odd, how her soft-

spoken, uncanny

twin and the wicked

child’s

tresses dye in

the midday sun;

it bleaches dust on

windows,

too — she’s

gone to market, slown

down like

cartwheels in

a gloaming

heat.

Bio: Eliot Cardinaux

Poet, Pianist, Multimedia Artist

www.eliotcardinaux.com

Sources

Overview

Mudge, Jean McClure. Emily Dickinson and the Image of Home. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1975, xvii-xviii, 1, 13.

History

Atlantic Monthly, August 1862

Hampshire Gazette, September 2, 1862

Springfield Republican, August 30, 1862

Biography

Browne, Patrick. “‘Auld Lang Syne’ Banned.” Historical Digression. January 2, 2011.

Bouson, J. Brooks. “Emily Dickinson and the Riddle of Containment.” Emily Dickinson Bulletin 31 (1977), 33-35.

Mudge, Jean McClure. Emily Dickinson and the Image of Home. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1975, 6-7.

Thompson-Rizzo, Patricia. “Gone-to-Kansas: A Reading of Dickinson's L182.” RSA Journal 14, 2003: 17-35, 21-22.

I miss seeing the composers’ names of the performances on u-tube. Is it possible to list them?

Margaret H. Freeman

Mayrifield Institute for Cognition and the Arts

Margaret, So glad there is interest in the You-tube performances. We are working on the You-tube channel. There is information on the composer after each video, scroll down. All the recordings so far are by Aaron Copland, but my daughter Rebekah is interested in learning and recording more settings of Dickinson poems. She’s also directing a small chamber group this year and it would be wonderful if they could sing some of Alice Parker’s settings. I was deeply moved by hearing them, and her speak, at the recent EDIS conference. We have so much fun talking about the poems and how to sing them. Rebekah says the music Copland composed very much represents an interpretation of the poems and her accompanist Annemieke says the musical notation also includes visual references to images in the poems.

Today I was surprised and very excited to receive an email from the poet and scholar Ivy Schweitzer that my recent poems “Passing, Exaltation, Pastorale,” were published as this week’s reflection on White Heat.

Since I had sent the poems but wasn’t anticipating them being published on such short notice, I decided to write a prose reflection in addition to the verse she published. The topic of this week’s entry on White Heat is “Home.” Since, as you will see, the events that correlate on this week in 1862 pertain to immigration, and Ivy decided to focus on homelessness, I though I’d share this.

The rents are rising. Homelessness is on the rise as a statistic. Or I might be wrong, but I notice myself more aware of my privilege every time I walk to the store, and if the precariousness of that position in society: that of having a roof over one’s head. As I settle into a new living situation (I’ve been in Western Massachusetts for just over a month), I have felt the contention of the forces of capitalism at its decay quite potently, to put it mildly. Not having bus fare. Having to work odd jobs to scrape by. These are not news to me. But all around me I see people struggling. From the man who sleeps out back of the bookstore where I work at, who asked to put in the good word. He was trying. To the hobos that lay under the bridge a block from my house in Northampton. I often stop off with a bottle of water or a nip, and hand them a couple of cigarettes. I can hardly afford it.

The fact that helping people sustain basic needs puts me in jeapordy is a good thing because it teaches me the lesson of what it means to go without. In an age where those in power are taking everything for themselves, including the rights of citizens to their own citizenship, it is empowering to learn how to survive with the bare minimum, and I think it deepens the empathy I have for people who are living this as a constant, often not by choice. As we near the third decade of what was once a new century, I find it poised within me to stand guard over people who have less because I know how it feels.

I just wanted to share that in terms of what this is teaching me, I think I have a long way to go, but that accepting this life has taught me that I’m not alone.

Enjoy the poems, peruse the blog (Ivy has put together a great project on a phenomenal poet), and think a little on others. It will do you good.

Eliot, such a profound reflection on our times and about the very town and neighborhood that Dickinson grew up in. Even from her home of relative comfort and ease, she knew or could imagine what literal homelessness felt like. Most of us cannot imagine being so bereft, but it is all around us. I visited Los Angeles recently and was appalled to see veritable tent cities across downtown and Venice. We need to find ways to address this situation and work against the invisibility it promotes. Thank you for your words and deeds.