On Choosing the Poems

Though Edward Dickinson was an influential figure in Emily Dickinson’s upbringing, education, and personal life, it is difficult to pinpoint his influence on her poetry. Thomas Johnson discovered one such clue, an “unwritten note” on the back of a poem that reads “Dear Father—Emily.” Taken as a visual metaphor, Edward Dickinson’s influence is relegated to the backdrop of Dickinson’s oeuvre, just as his routine absence created a distant rapport between father and daughter. As a textual clue, the note’s brevity recalls that same absence. Moreover, Edward Dickinson is not explicitly mentioned in any of his daughter’s poems, though she discusses him in the occasional letter to Austin or Higginson. His presence in her work, just as in her life, is markedly absent, but that is not to underestimate his influence.

Owen Thomas, writing in 1969, points to subtler ways in which Edward Dickinson might have influenced his daughter’s work, though the evidence is frequently inconclusive. Dickinson wielded an extensive and precise legal vocabulary, one that she inherited from her father’s deep commitment to his career. She repeatedly returns to themes of domestic economy, undoubtedly in response to growing up in one tightly managed by her father, and relies heavily on monetary metaphors. Finally, her poems often exhibit a keen attention to power and its execution. In 1862, she wrote:

He put the Belt around my life –

I heard the Buckle snap – (F330)

Edward Dickinson’s authoritative hand in the life of the Homestead and his intense sense of social mores were certainly a “Belt” around Emily Dickinson’s life. Though she rarely let her father enter directly onto the page, his influence is apparent in her observations of the workings of power—a poet hearing the “Buckle snap.”

Sources

Thomas, Owen. “Father and Daughter: Edward and Emily Dickinson.” American Literature 40.4 (Jan. 1969): 510-23.

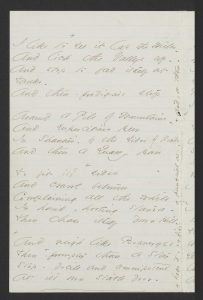

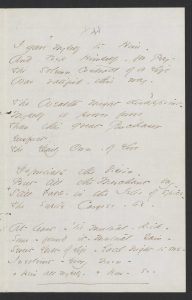

Where bells no more affright the morn (F114 A, J112)

Where bells no more affright the morn -

Where scrabble never comes –

Where very nimble Gentlemen

Are forced to keep their rooms -

Where tired Children placid sleep

Thro’ centuries of noon

This place is Bliss – this town is Heaven -

Please, Pater, pretty soon!

“Oh could we climb where Moses stood,

And view the Landscape o’er”

Not Father’s bells – nor Factories -

Could scare us any more!

EDA manuscript: "Originally in Amherst Manuscript #fascicle 83 – So from the mould – asc:8061 – p. 2. Courtesy of Amherst College, Amherst, MA. First published in Poems (1890), 75, as two quatrains."

One of the twenty-eight poems bound in fascicle 5, “Where bells no more affright the the morn” (F114) is dated to 1859, but we include it as one of the few poems, if not the only one, in which Dickinson directly mentions her father. It is also one of the few poems in which she directly rewrites Protestant hymns—could there be a connection?

“Father’s bells” refers to the bell Edward used to wake his children, a discipline that informs the poem's conceit from the first stanza: the speaker imagines a “where,” a place—marked by anaphora in lines 1, 2, 3, and 5—outside of the scheduled awakening “bells,” which the speaker associated with the regimented “Factories” that constrain their workers's freedom. That same stanza elaborates this imagined space as one where “very nimble Gentlemen / Are forced to keep their rooms.” In Dickinson’s gendered culture, it was women, like her mother in her final long illness, who frequently kept to their rooms. The speaker imagines a place where “nimble gentlemen,” like her father, are secluded and, thus, decentered, giving the poem an anti-patriarchal, proto-feminist edge.

Annie Finch notes that Dickinson associated iambic pentameter, the meter of Shakespeare and Milton, with patriarchy. In a subtle subversion of this form, Dickinson writes the stanzas of “Where bells no more affright the morn” in hymn meter: four-line stanzas of alternating iambic tetrameter and iambic trimeter. In the strictly regimented domestic economy of Edward Dickinson’s home, the Homestead, the idea of children sleeping past noon, let alone “Thro’ centuries of noon,” would have been considered reprehensible, if not heretical. Interestingly, line 7, breaks that meter with a feminine ending in the word “Heaven,” as if to say that the else-“where” the speaker imagines in this poem beyond paternal surveillance and discipline might be heaven if only it were feminine in character.

As Thomas Johnson indicates, the third stanza of Dickinson’s poem parodies the fourth stanza of Isaac Watts’s hymn, “There is a land of pure delight”:

Could we but climb where Moses stood,

And view the landscape o’er,

Not Jordan’s stream, nor death’s cold flood

Should fright us from the shore.

Dickinson’s playful revision, “Not Father’s bells – nor Factories –,” associates the regimented world of factories and Edward’s household discipline; specifically, Dickinson relates “Father’s bells” to “Jordan’s stream” and “Factories” to “death’s cold flood.” But there is a serious note here, too. There were factories in the small town of Amherst at this time, and this is one of the few poems that recognizes such class distinctions.

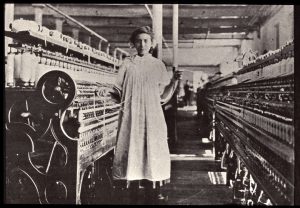

Dickinson would have also known about the young women who worked in the mills of Lowell, Massachusetts, from her year at Mt. Holyoke Seminary. According to Daneen Wardrop, several of Dickinson's classmates at the Seminary had worked in the mills to save money to attend the school, which the school’s founder, Mary Lyon, established precisely to provide opportunities for that class of women. Furthermore, from 1840-45 the “mill girls” of Lowell published the Lowell Offering, a collection of their writings. Just as this poem proposes an alternative space outside the strictures of patriarchal power (e.g., bells, factories, and masculine meter forms), its parodic use of intertextuality likens the imagined “where” as sacred, but difficult to reach.

Sources

Finch, Annie. The Body of Poetry: Essays on Women, Form, and the Poetic Self. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan, 2005. .

Dickinson, Emily. Poems: Including Variant Readings Critically Compared with All Known Manuscripts. Ed. Thomas Johnson. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1955, 114.

Wardrop, Daneen. Emily Dickinson and the Labor of Clothing. Durham, NH: University of New Hampshire, 2009, 70.

For more on a famous “Lowell Mill girl,” Lucy Larcom (1824-1893), who published poetry in the Lowell Offering and became a noted writer and school teacher, see the module “Diverging Domesticities” on the collaborative Public Humanities website HomeWorks: Learning from 19th Century Women about the Richness of “Staying at Home.” That module puts Dickinson, the “queen of quarantine,” into conversation with Larcom and another contemporary writer, Sarah Winnemucca (1844-1891), a noted member of the Northern Paiute Tribe of present day Nevada.

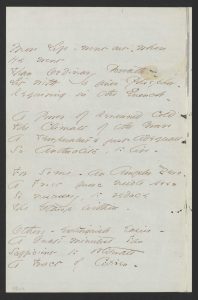

I like to see it lap the miles (F383A, J 585)

I like to see it lap the Miles –

And lick the Valleys up –

And stop to feed itself at

Tanks –

And then – prodigious step

Around a Pile of Mountains –

And supercilious peer

In Shanties – by the sides of Roads –

And then a Quarry pare

To fit it's +sides

And crawl between

Complaining all the while

In horrid – hooting stanza –

Then chase itself down Hill –

+And neigh like Boanerges –

Then – +prompter than a Star

Stop – docile and omnipotent

At it's own stable door –

variants: +Ribs +then +punctual as

EDA manuscript: "Originally in Poems: Packet XXVII, Fascicle 19. Includes 13 poems, written in ink, ca. 1862. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. First published in Poems (1891), 39, with the alternative for line 15 adopted and stanza 3 as a quatrain."

As mentioned in this week's Biography section, part of Edward Dickinson’s political agenda and one of his passions was bringing a railroad to Amherst, which he successfully did in 1853, becoming the president of the Amherst & Belchertown Railroad. On May 16 of that same year, Dickinson wrote to her brother Austin praising the railroad’s arrival:

While I write, the whistle is playing, and the cars just coming in. It gives us all new life, every time it plays. How you will love to hear it, when you come home again!

“New life” is strong diction for Dickinson, and her comment exudes an ephemeral enthusiasm about the innovation. Johnson, in his commentary on Letter 123, writes that

the first regular trip of a passenger train on the Amherst and Belchertown Railroad was made on May 9,

just a week before Dickinson wrote to her brother. It was certainly an exciting affair.

Sharon Leiter points out that Dickinson’s original excitement waned when she wrote to Austin a month later about a train coming in from New London:

The New London Day passed off grandly—so all the people said—it was pretty hot and dusty, but nobody cared for that. Father was as usual, Chief Marshal of the day, and went marching around the town with New London at his heels like some old Roman General, upon a Triumph Day. Carriages flew like sparks, hither, and thither and yon, and they all said t’was fine. I spose it was—I sat in Prof Tyler’s woods and saw the train move off, and then ran home again for fear somebody would see me, or ask me how I did. (L127)

After a month’s time to process, Dickinson reckons with the train’s cargo: large crowds, festivities, unfamiliar faces, and—as she parodies above—her father parading around like a Roman General. She associates the train, more than anything, with the successes of her father for having brought it to Amherst, and she writes of it all with a playful irony. That Dickinson observed New London Day from the seclusion of the woods calls into question the first line of her poem, “I like to see it lap the Miles.” Does she really like it? Or is she keeping a safe distance? This poem, written in 1862, nine years after the railroad’s inauguration, offers her poetic perspective on the railway. Her Webster's defined “Boanerges” as “Sons of thunder. Matth. iii.” The Lexicon expands on this:

nickname that Christ gave to the two sons of Zebedee; [fig.] disciple; apostolic messenger; loud orator; vociferous preacher; subject of an 1858 biographical sketch by James Challen.

Leiter argues that the formal aspects of the poem—syntax, punctuation, meter—create a mimetic evocation of a train:

Syntactically, the entire poem consists of a single sentence, with the subject-predicate “I like to see” followed by by an extended train (pun intended) of objective complements describing what “it” does. In this way, the poem, like the train, accelerates into its journey, gathering steam and growing ever wilder, until its sudden stop. Dickinson’s use of dashes mimics the jerkiness of the locomotive movement.

Sources

Dickinson, Emily. The Letters of Emily Dickinson. Eds. Thomas Johnson and Theodora Ward. 3 vols. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1958.

Hallen, Cynthia, ed. Emily Dickinson Lexicon. Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University, 2007.

Leiter, Sharon. Critical Companion to Emily Dickinson: A Literary Reference to Her Life and Work. New York, NY: Facts on File, 2007.

Sewall, Richard B. The Life of Emily Dickinson. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1974.

Did we disobey Him? (F299, J267)

Did we disobey Him?

Just one time!

Charged us to forget Him –

But we could'nt learn!

Were Himself – such a Dunce –

What would we – do?

Love the dull lad – best –

Oh, would'nt you?

EDA manuscript: "Originally in Poems: Packet XX, Fascicle 10. Includes 13 poems, written in ink, ca. 1861. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. First published in Bolts of Melody (1945), 124, from a transcript of B (a tr366)."

This two stanza poem is an interesting variation on the short form of the hymn meter: 6365 6454 syllables rhyming abab, with slant rhymes on time/learn and Dunce/best. It takes on the child persona’s voice and the initial reference to “disobedience” suggests the speaker refers to a father figure or other disciplinarian. But as this short poem unfolds, it becomes clear that this fatherly figure could also be a disinclined or forbidden love interest (“Charged us to forget Him”) or, given the capitalization of the pronoun “Him,” it could be God. Though why would an authoritarian father chastising a naughty child, or a powerful God disciplining a disobedient believer, demand forgetfulness? The word “disobey” also suggests the disobedience of Adam and Eve, the “just one time” that caused the Fall and exile from Eden.

The second stanza performs a familiar Dickinson inversion. The fatherly or Master figure is cruel and penalizing. The speaker imagines the roles reversed and, putting herself in the position of power acts in a diametrically opposed way. Instead of rejecting the “Dunce,” a word that suggests a dim or unruly student sitting in the corner wearing a “dunce cap,” the speaker would “Love the dull lad – best.” As in “I’m nobody! Who are you?” the speaker implicates the reader in the subversive reversal with the final question. And we realize the speaker is not addressing the figure in ostensible power, but an onlooker to her disobedience in a playfully rebellious way, even questioning whether it was disobedience at all.

In another familiar Dickinson ploy, the word “Dunce” contains its opposite meaning and communicates some of the amused tolerance that characterized Dickinson's attitude towards her stern father and the dry humor she and Austin developed to keep him at bay. Her Webster’s offered this fascinating comment:

Dunce is said by Johnson to be a word of unknown etymology. Stanihurst explains it. The term Duns from Scotus [John Duns Scotus, the celebrated scholastic theologian] 'so famous for his subtill quiddities,' he says, 'is so trivial and common in all schools, that whose surpasseth others either in cavilling sophistrie, or subtill philosophie, is forthwith nicknamed a Duns.' This, he tells us in the margin, is the reason 'why schoolmen are called Dunses.' (Description of Ireland, p. 2.) The word easily passed into a term of scorn, just as a blockhead is called Solomon; a bully, Hector; and as Moses is the vulgar name of contempt for a Jew.” – Dr. Southey's Omniana, vol. i. p. 5. E.H.B.] I have little confidence in this explanation. – N.W. [Nathaniel Webster].

Sources

Hallen, Cynthia, ed. Emily Dickinson Lexicon. Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University, 2007.

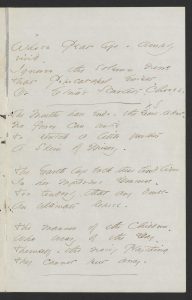

More Life – went out – when He (F415, J422)

More Life – went out – when

He went

Than Ordinary Breath –

Lit with a finer Phosphor –

Requiring in the Quench –

A Power of Renowned Cold,

The Climate of the Grave

A Temperature just adequate

So Anthracite, to live –

For some – an Ampler Zero –

A Frost more needle keen

Is nescessary, to reduce

The Ethiop within.

Others – extinguish easier –

A Gnat's minutest Fan

Sufficient to obliterate

A Tract of Citizen –

Whose Peat life – amply

vivid –

Ignores the solemn News

That Popocatapel exists –

Or Etna's Scarlets, Choose –

EDA manuscript: "Originally in Poems: Packet X, Mixed Fascicles. Includes 14 poems, written in ink, ca. 1858-1862. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. First published in Yale Review, 25 (Autumn 1935), 76, and Unpublished Poems (1935), 4, the first four stanzas."

We discussed this poem in the post on Choosing, looking at its description of the effects of choosing or taking control of the decisions in one’s life, which are likened to erupting volcanoes mentioned in the last stanza: “Etna,” an active volcano on the Italian island of Sicily, and Popocatapel, a volcano in central Mexico, described in Dickinson’s Webster’s as

a towering volatile peak; mountain capable of erupting in spectacular flames and lava flows.

Dickinson might have imagined Edward’s quiet but powerful personality as the pressurized and damped down power of a volcano, but she reserved that image mostly for herself, and images of Italy for Susan.

We can spy Edward in the allusions in this poem to a personality aligned with frost, cold, repression, death, and renown: “A Power of Renowned Cold / The climate of the Grave.” This figure epitomizes those people who require “an Ampler Zero – / A Frost more needle keen … to reduce/ The Ethiop within.” Dickinson associated “the Ethiop” with hot climates and sensual natures, while her father spent much psychic energy being rational, guarded, and distant. Such a frosty person, who had “extinguished” and “obliterated” the fires within, would be one who “Ignores the solemn News” of the existence, not least the eruptions, of volcanoes—ignores the creative white heat of his daughter. The other word that conjures Edward Dickinson is “Citizen,” for he was certainly a distinguished “freeman of a city … entitled to its franchises” (Webster's definition), though he was dubbed the “Squire” of Amherst, a term that turns its Whiggish nose up at the democratic whiff of “citizen.”

Sources

Hallen, Cynthia, ed. Emily Dickinson Lexicon. Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University, 2007.

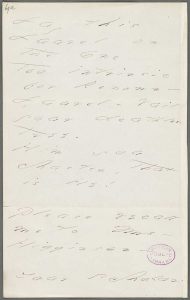

I gave myself to Him (F426, J580)

I gave Myself to Him –

And took Himself, for Pay –

The solemn contract of a Life

Was ratified, this way –

The Wealth might disappoint –

Myself a poorer prove

Than this great Purchaser

suspect,

The Daily Own – of Love

Depreciate the Vision –

But till the Merchant buy –

+Still Fable – in the Isles of spice –

The subtle Cargoes – lie –

At least – 'tis Mutual – Risk –

Some – found it – Mutual Gain –

Sweet Debt of Life – Each Night to owe –

Insolvent – every Noon –

variants: +How – • so –

EDA manuscript: "Originally in Poems: Packet XXXII, Mixed Fascicles. Includes 12 poems, written in ink, ca. 1862. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. First published in Poems (1891), 93, with neither alternative adopted."

This poem illustrates Edward’s influence on his daughter not so much in terms of thematic content as structuring imagery. Owen Thomas, who studies their relationship, traces the evolution of images of wealth, value, the market place, and legal processes in Dickinson’s poetry and argues that in 1862, her second period of poetic maturity dominated by “ crisis,” her vocabulary

suggests that her father’s orderly view of life was, in part, a source of strength.

Images of law come to dominate, and Thomas finds

a new concern for spiritual and emotional wealth which contrasts with the earlier intellectual images of rather vague acquisition. The imagery in many of the poems reveals an intense desire to define the emotional treasures of life.

“I gave myself to Him” is a prime example. Thomas comments:

The legal and financial images operate effectively together and lead naturally to the powerful "insolvent" of the final line.

Because they recur in other poems of this time, Thomas deduces that by this period, for Dickinson

images of the market place had acquired an emotional as well as an intellectual significance.

To be sure, there is deep resonance and erotic power in the imagery of mutual giving and in phrases like “The Daily Own – of Love” and “Sweet Debt of Life – Each Night to owe –/ Insolvent – every Noon.” The image of the lovers “spending” themselves each night and, thus, incurring a debt that makes them insolvent, so they have to give/pay out more; that last word shimmers with the mystery of intimacy and a hint of persons dissolving into each other.

Sources

Thomas, Owen. “Father and Daughter: Edward and Emily Dickinson.” American Literature 40.4 (Jan. 1969): 510-23, 513-15.

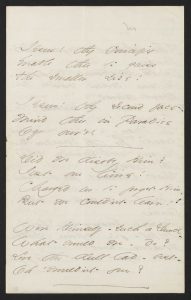

Lay this Laurel on the One (F1428C, J1393)

Lay this

Laurel on

the One

Too intrinsic

for Renown –

Laurel – vail

your deathless

Tree –

Him you

chasten, that

is He!

EDA manuscript: "Originally in Amherst Manuscript # 268, Amherst. Courtesy of Amherst College, Amherst, MA. First published in Poems (1891), 230, the stanza from the letter to Higginson (C) from his transcript."

Although this poem is dated to 1877, three years after Edward died, in the view of biographer Richard Sewall, it

is a remarkable distillation of the thought and feeling, attitude and appraisal, that [Dickinson’s] ultimate view of her father became.

It is also intimately connected to Thomas Wentworth Higginson, who perhaps served as a more approachable father figure for Dickinson.

On the second anniversary of Edward’s death, Dickinson sent a poignant comment to Higginson:

When I think of my Father’s lonely Life and his lonelier Death, there is this redress—

Take all away —

The only thing worth larceny

Is left — the Immortality (L457)

On the third anniversary of her father's death, she sent Higginson a poem that distilled an elegy titled “Decoration” Higginson published in Scribner’s Monthly for June 1874, the month her father died. Dickinson expressed her appreciation to Higginson for his poem, a moving but conventional offering for Memorial Day, which she said “has assisted that Pause of Space which I call Father –” (L418). “Lay this Laurel on the one” is her rewriting of Higginson’s “Decoration,” (L503) which, he later told Mabel Loomis Todd,

is the condensed essence of that & so far finer.

Sources

Dickinson, Emily. The Letters of Emily Dickinson. Eds. Thomas Johnson and Theodora Ward. 3 vols. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1958.

Sewall, Richard. The Life of Emily Dickinson. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1980,

71-72.