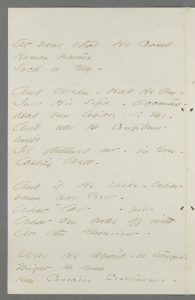

To know just how He suf –

fered – would be dear –

To know if any Human eyes

were near

To whom He could entrust

His wavering gaze –

Until it settled broad – on

Paradise –

To know if He was patient –

part content –

Was Dying as He thought –

or different –

Was it a pleasant Day

to die –

And did the Sunshine

face His way –

What was His furthest mind –

of Home – or God –

Or What the Distant say –

At News that He ceased

Human Nature

Such a Day –

And Wishes – Had He any –

Just His Sigh – accented –

Had been legible – to Me –

And was He Confident

until

Ill fluttered out – in Ever –

lasting Well –

And if He spoke – What

name was Best –

What + last +first

What one broke off with

At the Drowsiest –

Was he afraid – or tranquil –

Might He know

How Conscious Consciousness – could grow –

Till Love that was – and

Love too best to be –

Meet – and the Junction

+be Eternity +mean

Link to EDA manuscript. Originally in Packet XL, Fascicle 32, ca. 1862. Courtesy of the Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. First published in Poems (1890), 128-29, with the alternatives for lines 4 (“firm”) and 19 adopted.

While Johnson dates this poem to 1862, Franklin dates it to the second half of 1863. It is important in this discussion because it reveals Dickinson’s familiarity and concern with what Cristanne Miller calls “the Victorian death culture, where dying was treated as a semi-public ritual.” The age’s concern with a “good death” builds on the long tradition of the ars moriendi or “craft of dying,” which had several stages and requisite signs. Protestant followers of Calvin believed that a person’s death was an index of the state of their souls: if they died willingly, forsaking things of the world, accepting their pain and dissolution, seeing apparitions, and calling on God, it was reasonably certain they were one of the “elect” predestined by God to eternal glory. This explains why, in many letters, Dickinson asks or gives details on how someone died, what they said, who was there, etc.

Barton Levi St. Armand argues that Victorian sentimentalists added another aspect to the ars moriendi, which influenced Dickinson, that “the dead themselves were considered frozen emblems of the resurrection, actual tokens of the longed-for afterlife.” This accounts for the “sculptural” references in Dickinson’s poems, references to “chill,” “coldness,” and “stone,” as if the dead become like marble statues.

Miller notes that many popular poems recounted soldiers dying in the arms of their comrades, speaking last words about their wives or mothers, and looking forward to heaven. While Dickinson recounted such details about Frazar Stearns’ death to her Norcross cousins, Miller argues that this poem moves through those details and the “sentimental idiom” found in popular poetry about the war dead

to the more idiosyncratic, and from the concerns of popular death culture to more philosophical concerns with dying.

The opening stanzas contain many elements of the popular formula—the speaker asks if the dying was surrounded by friends, was he patient, content, did he have wishes to be remembered to loved ones, was he confident, afraid, tranquil, what were his last words. But the last stanza, Miller argues, “uses epistemological discourse characteristic of Dickinson’s most serious poetry” and raises this poem above the crowd.

Sources

- Miller, Cristanne. Reading in Time: Emily Dickinson in the Nineteenth Century. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2012, 163-64.

- St. Armand, Barton Levi. Emily Dickinson and Her Culture: The Soul’s Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984, 52-65.

- McCabe, Brian. “Amherst and the Civil War.” All Things Dickinson: an Encyclopedia of Emily Dickinson’s World. Ed. Wendy Martin. 2 vols. Greenwood Press, 2014. Ebook, 176-78.