On Choosing the Poems

As discussed in the post for this week, the death of Frazar Stearns made the war and its ghastly toll extremely personal for Emily Dickinson, and the effect on her poetry is palpable. Dickinson wrote several poems, included here, that scholars attribute directly to the effects of this death, Dickinson’s probable attendance at Stearns’s emotional funeral in Amherst, and the ceremony in April at which her father presided, where Amherst College received the Confederate cannon to memorialize Stearns and the other casualties of the battle of New Bern.

As discussed in the post for this week, the death of Frazar Stearns made the war and its ghastly toll extremely personal for Emily Dickinson, and the effect on her poetry is palpable. Dickinson wrote several poems, included here, that scholars attribute directly to the effects of this death, Dickinson’s probable attendance at Stearns’s emotional funeral in Amherst, and the ceremony in April at which her father presided, where Amherst College received the Confederate cannon to memorialize Stearns and the other casualties of the battle of New Bern.

These poems give us a good sense of Dickinson’s reactions to the war and to the pervasive rhetoric in the North of Christian justification (think, for example of Julia Ward Howe’s popular “Battle Hymn of the Republic”), of her reactions to a heightened sense of tragedy and death, and to her involvement in what scholars call “the Victorian culture of death,” which was also heightened by the war.

While Dickinson wrote directly about the war only rarely, many of her poems from this period are infused with a sharp awareness of the conflict, its toll, and the moral conflicts it presented. Poems like “It was not death, for I stood up,” have been read as almost solipsistic meditations on her personal experience of (often) romantic loss, or religious despair, or as evidence of her madness and psychosis. But if we read this poem in the context of the war and Dickinson’s haunting by the death of young heroes like Frazar Stearns, the poem opens up into new, more dramatic and insightful renderings of a soldier’s blunted reactions to battle.

This week’s poems:

Victory comes late (F195A, J690)

Victory comes late –

Victory comes late –

And is held low to freezing

lips –

Too rapt with frost

To take it –

How sweet it would have tasted –

Just a Drop –

Was God so economical?

His Table’s spread too high

for Us –

Unless We dine on Tiptoe –

Crumbs – fit such little mouths –

Cherries – suit Robins –

The Eagle’s Golden Breakfast

strangles – Them –

God keep His Oath to Sparrows –

Who of little Love – know

how to starve –

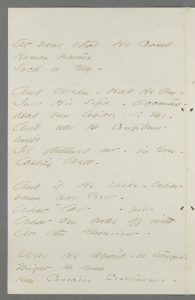

EDA manuscript: "Originally in Letter to Samuel Bowles, [1861] p. 1. Library ID: YCAL MSS 201. Courtesy of Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Library, Yale University, New Haven, CT. Later copied into Fascicle 34. First published in Poems (1891), 49, from the fascicle copy (B), with lines 12 and 14 divided into two lines each."

Dickinson originally sent this poem in a letter to Samuel Bowles, and though the dating of the letter and poem is unclear, some scholars believe it is an elegy for Frazar Stearns, whose death at the battle of New Bern shocked everyone in Amherst and particularly affected the Dickinson family. The poem closely replicates what Dickinson knew about the circumstances of Stearns’s death from reports and details she recounted to her Norcross cousins in Letter 255, quoted in full in the Biography section of the post.

The poem is an excellent example of Dickinson’s free verse poems, discussed in an earlier post on Meter. In her discussion of Dickinson’s use of free verse, Cristanne Miller diagrams this poem’s structure and concludes that it

maintains a rough iambic undertone, but the combination of highly irregular line lengths, no pattern of even- and odd-numbered syllables, and the unevenness of the meter prevent all sense of metrical regularity.

The lack of regularity, however, suits the poem’s ironic tone that questions the wisdom of a God who seems, in this untimely death, not to have kept his “vow.” In the second stanza, Dickinson alludes to two verses from the gospel of Matthew:

Matthew 6:26: Look at the birds of the air: They do not sow or reap or gather into barns–and yet your Heavenly Father feeds them. Are you not much more valuable than they?

Matthew 10:29: Are not two sparrows sold for a penny? Yet not one of them will fall to the ground apart from the will of your Father.

Barton Levi St. Armand notes that Stearns had an early conversion during the religious revivals in Amherst but argues that Stearns had begun to share Dickinson’s “burned-child’s response to transforming religious fires,” which took the form of a

self-sacrificial fanaticism … [to] the Union cause, and he too courted death as both a test and a justification of his faith.

Not just the Congregational God, but the state also comes in for critique in this poem. Does the image of “Eagle’s golden breakfast” suggest the Union government, whose symbol is the bald eagle? Shira Wolosky comments that the poem

moves from a concern with military to a concern with theological victory, and the latter subsumes the former.

Sources

Miller, Cristanne. Reading in Time: Emily Dickinson in the Nineteenth Century. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2012, 114-15.

St. Armand, Barton Levi. Emily Dickinson and Her Culture: The Soul’s Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984, 110-11.

Wolosky, Shira. Emily Dickinson: A Voice of War. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1984, 61.

Our journey had advanced (F453A, J615)

Our journey had advanced –

Our feet were almost come

To that odd Fork in Being’s

Road –

Eternity – by Term –

Our pace took sudden awe –

Our feet – reluctant – led –

Before – were Cities – but Between –

The Forest of the Dead –

Retreat – was out of Hope –

Behind – a Sealed Route –

Eternity’s +White Flag – +Before –

And God – at every Gate

+cool +in front –

EDA manuscript: "Originally in Packet XXXIV, Fascicle 21, ca. 1862. First published in Poems (1891), 206, as “The Journey,” with the alternatives not adopted. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA."

Unlike the previous poem, which was an example of Dickinson’s free verse, this poem is a nearly perfect example of a hymn meter called “short meter,” a four line stanza of 6686 syllables rhyming abab, a form that Dickinson used frequently. Here, the regularity of the meter is a counterpoint to the references in the poem to disturbed rhythm: “Our pace took sudden awe / Our feet – reluctant – led” to the fork in “Being’s Road” that marks a change in existence and points to Eternity.

Is this poem, as Greg Johnson suggests, “an especially complex vision of the relationship between death and perception”? The poem takes on sterner tones when we note, as Virginia Oliver does, “the battle-field imagery” through which “Dickinson portrays death as a necessary transition.” She further suggests,

The poem can even be considered a gloss on her more famous poem, “Because I could not stop for Death.”

Cristanne Miller reads the poem as a comfort for the war dead. She speculates that the poem “uses what may be a soldier’s voice to hypothesize that” beyond the forests laced with the bodies of fallen soldiers lies “certain reward.” And though “Retreat” was not an option in life as in death, the “White Flag” of truce betokens the release of “Eternity” with “God – at every Gate,” welcoming the dead. She concludes that

reading Dickinson’s poems in concert with war poems published in widely circulated periodicals reveals that many of her poems adopt the vocabulary, tone or idiom of popular war poetry.

Sources

Johnson, Greg. Emily Dickinson: Perception and the Poet’s Quest. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1985, 183-85.

Miller, Cristanne. Reading in Time: Emily Dickinson in the Nineteenth Century. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2012, 172.

Oliver, Virginia. Apocalypse of Green: A Study of Emily Dickinson’s Eschatology. American University Studies. Series 24: American Literature 4. New York; Lang, 1989, 87-88, 230-31.

When I was small a Woman died (F518 A, J569)

When I was small, a Woman died –

Today – her Only Boy

Went up from the Potomac –

His face all Victory

To look at her – How slowly

The Seasons must have turned

Till Bullets clipt an Angle

And He +passed + quickly round –

If pride shall be in Paradise –

Ourself cannot decide –

Of their imperial conduct –

No person testified –

But, proud in Apparition –

That Woman and her Boy

Pass back and forth, before my Brain

As even in the sky –

I’m confident, that Bravoes –

Perpetual + break abroad

For Braveries, +remote as this

+ In + Yonder Maryland –

+ went +softly

+ be–

+ just sealed

+ in +Scarlet

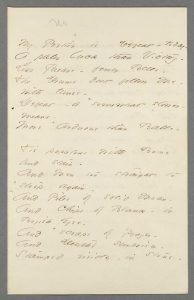

EDA manuscript: "Originally in Packet XIV, Mixed Fasciles, ca. 1860-1862. Copied into Fascicle 24 about Spring 1863. First published in Poems (1890), 145, with the alternatives not adopted. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA."

Scholars disagree on when this poem was written, sometime between 1861 and 1863. Dickinson biographer Richard Sewall dates it to early 1862 and calls it an elegy for Dickinson’s distant cousin Francis H. Dickinson, “the first man on Amherst’s quota to give us his life for his country,” killed in action at Ball’s Bluff, Virginia on the Potomac, near the Maryland border, October 21, 1861. Cristanne Miller notes that,

Dickinson changes the few details she appears to give of his life story,

that he was killed in Virginia, not Maryland, was not an only child, and she was twenty-three when his mother died, hardly “small.” But, Miller adds,

Individualizing elements do not play a significant role in Dickinson’s war verse.

More important is that, according to Miller,

[b]ecause Dickinson never refers to herself as a mother among the many named guises or dramatic perspectives she adopts in her poems (including boy, Czar, Earl, Queen, wife), it is notable that one of her most explicit responses to the war imagines the reunion of a mother and son in heaven. The strong bond between soldiers and their mothers gave rise to an extremely popular subset of sentimental war poems.

She notes that Dickinson would have read the story, “First of Our Dead” in the January 11, 1862 Springfield Republican about William Hunt, a soldier and “dutiful son” who penned a poem he sent home to his mother depicting a soldier on watch thinking of his mother who

prays for me …

Till, though the leagues lie far between,

This silent incense of her heart

Steals o’re my soul …

And we no longer are apart.

Compare this to Frazar Stearns’s last letter to his mother, quoted in this week’s post, where Stearns is more focused on the broader effects of the war and less specifically on his link to his mother. Miller cites other such popular poems,

which encourage mothers to give their sons gladly to the war.

Miller hears detachment in the poem and concludes that it

provides no moment of mourning for the son and no particular point of pride for the mother or the spectator.

Still, the imagery connects to Dickinson’s letters on Stearns’s death and suggests how haunted she was by it. In particular, the “Apparition” of the mother and son that “Pass back and forth, before my Brain” recalls the description in her letter to Bowles of Austin or Dickinson herself stunned into silence, repeating over and over the fact of Frazar’s demise.

Sources

Miller, Cristanne. Reading in Time: Emily Dickinson in the Nineteenth Century. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2012, 161-62, 173.

Sewall, Richard. The Life of Emily Dickinson. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1980, 536.

It is not dying hurts us so (F528A, J335)

[no image available]

It is not dying hurts us so –

‘Tis living hurts us more.

But dying is a different way,

A kind, behind the door –

The Southern custom of the bird

That soon as frosts are due –

Adopts a better latitude.

We are the birds that stay

The shiverers round farmers’ doors.

For whose reluctant crumb –

We stipulate – till pitying snows

Persuade our feathers Home.

EDA manuscript: "Originally, the poem was incorporated into a letter, now lost, to Louise and Frances Norcross on the occasion of the death of their father, Loring Norcross, on 17 January 1863. The text survives in Frances’s transcript (y-mssa mlt69-19, 432). First published in Letters (1894), 251, from ([A]); and Bolts of Melody (1945), 201, from a transcript of B (a tr440)."

When the father of her beloved cousins died in January 1863, Dickinson included this poem in a letter to them prefaced by words of comfort and memories of her uncle and his gentleness, as well as his attitude about death and her reaction to it:

Wasn’t dear papa so tired always after mamma went, and wasn’t it almost sweet to think of the two together these new winter nights? The grief is our side, darlings, and the glad is theirs. … Let Emily sing for you because she cannot pray (L278).

Dickinson repeats this idea, that death hurts the living more or hurts less than living, in other poems. The reference to the “Southern custom of the bird,” an allusion to migratory patterns, which are also a frequent metaphor for death, connects this poem to the “rebellion” on the part of the Southern states. Especially when Dickinson links herself and her cousins to the birds that do not migrate but remain, presumably, in the North.

“Shiverers” stands out as a choice of diction that is almost onomatopoeic. “Stipulate” jumps out as a word out of place in this natural scene, which is, of course, a metaphor for the larger issue of the pain death brings to the living. According to Dickinson’s Webster’s, the word contains a military resonance and even elaborates a reference to slavery:

to make an agreement or covenant with any person or company to do or forbear any thing; to contract; to settle terms; as, certain princes stipulated to assist each other in resisting the armies of France. Great Britain and the United States stipulate to oppose and restrain the African slave trade.

Sources

Dickinson, Emily. The Letters of Emily Dickinson. Eds. Thomas Johnson and Theodora Ward. 3 vols. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1958, 420-21.

Hallen, Cynthia, ed. Emily Dickinson Lexicon. Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University, 2007.

Sewall, Richard. The Life of Emily Dickinson. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1980, 632

To know just how He suffered (F688A, J622)

To know just how He suf –

fered – would be dear –

To know if any Human eyes

were near

To whom He could entrust

His wavering gaze –

Until it settled +broad – on

Paradise –

To know if He was patient –

part content –

Was Dying as He thought –

or different –

Was it a pleasant Day

to die –

And did the Sunshine

face His way –

What was His furthest mind –

of Home – or God –

Or What the Distant say –

At News that He ceased

Human Nature

Such a Day –

And Wishes – Had He any –

Just His Sigh – accented –

Had been legible – to Me –

And was He Confident

until

Ill fluttered out – in Ever –

lasting Well –

And if He spoke – What

name was Best –

What +last

What one broke off with

At the Drowsiest –

Was he afraid – or tranquil –

Might He know

How Conscious Consciousness – could grow –

Till Love that was – and

Love too best to be –

Meet – and the Junction

+be Eternity

+full • firm +first +mean

EDA manuscript: "Originally in Packet XL, Fascicle 32, ca. 1862. Courtesy of the Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. First published in Poems (1890), 128-29, with the alternatives for lines 4 (“firm”) and 19 adopted."

While Johnson dates this poem to 1862, Franklin dates it to the second half of 1863. It is important in this discussion because it reveals Dickinson’s familiarity and concern with what Cristanne Miller calls

the Victorian death culture, where dying was treated as a semi-public ritual.

The age’s concern with a “good death” builds on the long tradition of the ars moriendi or “craft of dying,” which had several stages and requisite signs. Protestant followers of Calvin believed that a person’s death was an index of the state of their soul: if they died willingly, forsaking things of the world, accepting their pain and dissolution, seeing apparitions, and calling on God, it was reasonably certain they were one of the “elect” predestined by God to eternal glory. Dickinson's This explains why, in many letters, Dickinson asks or gives details on how someone died, what they said, who was there, etc. As she did in her letters about Frazar Stearns's death. The question of his “election” may have has special relevance to Dickinson and in relation to his status as a Christian martyr.

Barton Levi St. Armand argues that Victorian sentimentalists added another aspect to the ars moriendi, which influenced Dickinson, that

the dead themselves were considered frozen emblems of the resurrection, actual tokens of the longed-for afterlife.

This accounts for the “sculptural” references in Dickinson’s poems, references to “chill,” “coldness,” and “stone,” as if the dead become like marble statues.

Miller notes that many popular poems recounted soldiers dying in the arms of their comrades, speaking last words about their wives or mothers, and looking forward to heaven. While Dickinson recounted such details about Frazar Stearns’s death to her Norcross cousins, Miller argues that this poem moves through those details and the “sentimental idiom” found in popular poetry about the war dead

to the more idiosyncratic, and from the concerns of popular death culture to more philosophical concerns with dying.

The opening stanzas contain many elements of the popular formula—the speaker asks if the dying person was surrounded by friends, was he patient, content, did he have wishes to be remembered to loved ones, was he confident, afraid, tranquil, what were his last words. But the last stanza, Miller argues,

uses epistemological discourse characteristic of Dickinson’s most serious poetry

and raises this poem above the crowd.

Sources

Miller, Cristanne. Reading in Time: Emily Dickinson in the Nineteenth Century. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2012, 163-64.

St. Armand, Barton Levi. Emily Dickinson and Her Culture: The Soul’s Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984, 52-65.

McCabe, Brian. “Amherst and the Civil War.” All Things Dickinson: an Encyclopedia of Emily Dickinson’s World. Ed. Wendy Martin. 2 vols. Greenwood Press, 2014. Ebook, 176-78.

My portion is Defeat – today (F704A, J639)

My Portion is Defeat – today –

A paler luck than Victory –

Less Paeans – fewer Bells –

The Drums dont follow Me -

with tunes –

Defeat – a +somewhat slower -

means –

More +Arduous than Balls –

Tis populous with Bone

and stain –

And Men too straight to

+ stoop again –

And Piles of solid Moan –

And Chips of Blank – in

Boyish Eyes –

And + scraps of Prayer –

And Death's surprise,

Stamped visible – in stone –

There's +somewhat prouder,

Over there –

The Trumpets tell it to

the Air –

How different Victory

To Him who has it – and

the One

Who to have had it,

would have been

Contenteder – to die –

+something dumber + difficult –

+bend +shreds + something

EDA manuscript: "Originally in Poems: Packet IX, Fascicle 33, dated ca. 1862. First published in Saturday Review of Literature, 5 (9 March 1929), 751, and Further Poems (1929), 126, with the alternatives adopted and the text in twenty-two lines without stanza division. Courtesy of the Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA."

This is another poem that could be read as spoken in a soldier’s voice, but this time, a soldier who has been defeated and is looking “Over there” at the victorious troops. It is somewhat unusual for being written in stanzas of six lines of 886886 rhyming aabaab. The voice has the musing detachment of someone who is in shock, what we would today call post-traumatic shock. For this speaker, “Defeat” feels like a more “Arduous,” and if we consider Dickinson's variant, "dumber" means of stopping action “than Balls,” because it is psychological rather than purely physical. It literally strikes one dumb.

In the arresting second stanza, the speaker describes a post-battle scene that is chaotic, fragmented, and rhetorically metonymic, in which nothing is whole or natural, and everything evinces the frozen or sculptural character Dickinson associated with death. It is a place populated by “Bone and stain” and “Piles of solid Moan,” an unforgettable image. “Boyish Eyes” contain “Chips of Blank” and “scraps of Prayer,” and the suddenness of death makes the faces of the fallen appear as if “in stone.”

For Cristanne Miller, the poem

questions conventional rhetoric of victory through a striking portrait of suffering on a battlefield.

Shira Wolosky argues that here, as in other poems about the war, Dickinson

scrupulously refrained from taking sides. She sympathized with the defeated without partisanship. She could not celebrate victory, regardless of the victors. … Instead, she is left with the problem of inexplicable suffering and with questions concerning the justice of God itself.

Sources

Miller, Cristanne. Reading in Time: Emily Dickinson in the Nineteenth Century. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2012, 154.

Wolosky, Shira. “Dickinson’s War Poetry: The Problem of Theodicy.” Massachusetts Review 25,1 (Spring 1984): 22-41, 35.

It was not death, for I stood up (F355A, J510)

It was not Death, for

I stood up,

And all the Dead, lie down –

It was not Night, for all

the Bells

Put out their Tongues, for Noon.

It was not Frost, for on my +Flesh + Knees

I felt Siroccos – crawl –

Nor Fire – for just +my marble feet +tw0

Could keep a Chancel, cool –

And yet, it tasted, like

them all,

The Figures I have seen

Set orderly, for Burial,

Reminded me, of mine –

As if my life were shaven,

And fitted to a frame,

And could not breathe

without a key,

And ’twas like Midnight,

some –

When everything that ticked –

has stopped –

And space stares – all around –

Or Grisly frosts – first Au –

tumn morns,

Repeal the Beating Ground –

But, most, like Chaos –

Stopless – cool –

Without a Chance, or spar –

Or even a Report of Land –

To justify – Despair.

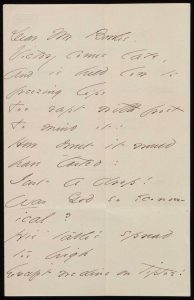

EDA manuscript: "Originally in Amherst Manuscript #fascicle 85. First published in Poems (1891), 222-23, with the alternatives not adopted. Courtesy of Amherst College, Amherst, MA."

Franklin dates this poem to summer 1862. Dickinson copied it into Fascicle 17. It is not usually considered a poem about the Civil War, but we follow Cristanne Miller’s lead in putting it into a war context, especially in relation to Dickinson’s response to the death of Frazar Stearns.

This harrowing poem revolves around an unnamed state—“It”—and what It is “not.” Definition through negative, as if the speaker’s state of feeling is so extreme, it cannot be named. The critical history of reading this poem draws on the biographical context of Dickinson’s suffering in love, her religious despair, her morbid response to death, or takes the poem to illuminate such aspects of her biography. But what if the poem’s speaker were a soldier traumatized by the horrendous experience of death and mutilation, which we know characterized Civil War battles? What if the poem were Dickinson’s attempt to dramatically capture the effects of that experience?

Maryanne Garbowsky comes close to this when she sees the poem paralleling

a panic attack in its physiological symptoms and its episodes of depersonalization where the victim is numb from extreme fear.

The speaker’s reference in stanza one to “all the dead” suggests not just one corpse in a coffin, as at a funeral, but many piled up or, as the speaker says in stanza three, “set orderly, for Burial,” as they would be in the aftermath of a battle, whether victory or defeat. Several photographs of Civil War battles illustrate just this kind of scene. Men in battle also describe time and sound stopping, and “chaos” taking over. And finally, the word “repeal” appears, in a slightly different form, in another poem of this period, which we discussed in the very first post and is most certainly about the war: “They dropped like Flakes” (F545A, J409). Dickinson’s first editors published this poem with the title, “The Battle-Field:”

They perished in the seamless Grass –

No eye could find the place –

But God can summon every face

On his Repealless – List.

Miller concludes about “It was not Death”:

Nothing makes this a war poem, and yet it powerfully evokes a state those who have survived battle might recognize.

Sources

Miller, Cristanne. Reading in Time: Emily Dickinson in the Nineteenth Century. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2012, 164-65.

Garbowsky, Maryanne. The House without a Door: A Study of Emily Dickinson and the Illness of Agoraphobia. Rutherford, NJ: Farleigh Dickinson University Press, 1989, 112-13.