I would not paint – a picture –

I’d rather be the One

It’s +bright impossibility

To dwell – delicious – on –

And wonder how the fingers feel

Whose rare – celestial – stir –

+Evokes so sweet a torment –

Such sumptuous – Despair –

I would not talk, like Cornets –

I’d rather be the One

Raised softly to +the Ceilings –

And + out, and easy on –

Through Villages of Ether –

Myself + endued Balloon

By but a lip of Metal –

The pier to my Pontoon –

Nor would I be a Poet –

It’s finer – Own the Ear –

Enamored – impotent – content –

The License to revere,

A + privilege so awful

What would the Dower be,

Had I the Art to stun

myself

With Bolts – of Melody!

+fair + Horizons + by –

+upborne +upheld + sustained

+ luxury + provokes

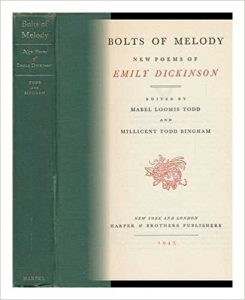

Link to EDA manuscript. Originally in Amherst Manuscript #fascicle 85. First published in Bolts of Melody (1945), xxxi, with the alternative for line 11 adopted. Courtesy of Amherst College, Amherst, MA.

This is the second poem in Fascicle 17, which Dickinson put together sometime in the summer of 1862. It shares sheet one with the first poem in the fascicle, “I dreaded that first Robin, so” (F347, J348). Its final, arresting line gives the title to the popular 1945 selection of Dickinson poems, Bolts of Melody, edited by Mabel Loomis Todd and her daughter, Millicent Todd Bingham.

Cristianne Miller notes that Dickinson “would have known several poems linking the arts of painting, music, and poetry (e.g., Keats’s “Ode to a Nightingale,” 1819). Susan Leiter observes that

Cristianne Miller notes that Dickinson “would have known several poems linking the arts of painting, music, and poetry (e.g., Keats’s “Ode to a Nightingale,” 1819). Susan Leiter observes that

Dickinson was a skilled cartoonist and accomplished pianist who composed original pieces, as well as a lover of the visual arts and of music. So she had some experience as maker and receiver in all three artistic realms.

Helen Vendler adds Keats’s “Ode on a Grecian Urn” to this genre, and notes that Dickinson reverses the usual comparison between the sister arts, asserting that it is better to be the audience of the art than the artist. But, Vendler goes on,

because of her witty and beautiful descriptions of the various arts, we cannot help believing that it is an artist who is speaking to us.

Scholars focus on the last stanza’s description of hearing poetry, in which the speaker wishes to become an “ear” to receive the poem aurally. The experience is bodily and profound: “Enamored – impotent – content,” “revere,” “privilege/luxury so awful”–that is, full of awe, “stun,” and finally, the startling image of the poet as a veritable Jove or Jehovah, hurling “Bolts – of Melody.” We might recall that the Puritans believed that grace came via the ear, through hearing the words of an inspired minister. Compare another use of the ear image from “I felt a Funeral, in my Brain,” F340, J280), in which the speaker is hearing the sounds of death:

And then I heard them

lift a Box

And creak across my Brain

With those same Boots of

Lead, again,

Then Space – began to toll,As all the Heavens were

a Bell,

And Being, but an Ear …

Scholars also find erotic and sexualized imagery throughout this poem, suggested in part by the word “Dower,” which, according to Dickinson’s Lexicon, could mean the property a man leaves his widow, the property a bride brings to her marriage, or the gift of a husband to his wife. The power of artists appears “masculine” for being active, while the audience seems feminine for being passive. Suzanne Juhasz and Cristianne Miller call the final image

autoerotic … an orgasmic moment that combines the phallic “Bolts” with the more feminine (in its pleasing tunefulness) “Melody.”

Cynthia Wolff interprets this amazing moment as a “tongue-in-cheek assertion of the necessarily ‘androgynous’ nature of the Poet,” which is especially important to the woman poet who, as artist, must take on active, assertive and conventionally “masculine” qualities. This reading echoes the thinking of the German philosopher, Arthur Schopenhauer, mentioned in this week’s post, who posited the existence of a “third sex” to describe the artist. Feminist critic Carolyn Heilbrun also championed androgyny as a means of including women in genius.

Sources

Dickinson, Emily. Emily Dickinson’s Poems, As She Preserved Them. Ed. Cristianne Miller. Cambridge: The Belknap Press, of Harvard University, 2016, 754.

Juhasz, Suzanne and Cristianne. “Performances of Gender in Emily Dickinson’s Poetry.” Cambridge Companion to Emily Dickinson. Ed. Wendy Martin. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002: 107-128, 125.

Heilbrun, Carolyn. Towards a Recognition of Androgyny. New York: W. W. Norton, 1973.

Leiter, Sharon. Critical Companion to Emily Dickinson: A Literary Reference to her Life and Work. New York: Facts on File, 2007, 135-36.

Vendler, Helen. Dickinson: Selected Poems and Commentaries. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University, 2010, 148-50.

Wolff, Cynthia. Emily Dickinson. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co., Inc. 1988, 171-72.