Disney's/Pixar's Coco Condones the Dehumanization of Migrant Bodies

An analysis of the “bridge” in the Disney/Pixar animated film, Coco.

This term, in LATS41: Representations of/from Latinx in the Media and the Arts, we explored the representations of Latinx identities, stories and socio-political issues. We watched films that documented the real life experiences of people crossing the Mexican-U.S. border. As we progressed in the class syllabus, so did the amount of Latinx produced films and other art forms. We watched a quasi-fictional representation of the border in La Misma Luna and documentaries with filmed re-enactments in Who Is Dayani Cristal? As much as it is powerful and shocking to view and listen to the real-life stories of people that have experienced the hardships of crossing the border: the life-threatening desert heat and cold, fearing for your life, fearing for your safety, leaving your homeland and your family only to find yourself alone, lost, unable to communicate, and criminalized for trying to find a better life for your family, it is important to keep in mind that some of these films can be triggering for those who have personally experienced these hardships. In an Ivy League setting where Latinx students make up less than 10% of the student body, watching these films can become trauma tourism where the traumas of those that have lived these hardships are placed on a big screen for others to consume, analyze, and discuss.

Although we see the border depicted in documentary films and fictional films based on real-life events, we often overlook the ways in which ideas of the border are reinforced and implemented in more fantastic forms of media such as animated films. We underestimate the influence that animated films have on socio-political issues, sometimes dismissing their influence all together because of their genre, but it is important to consider how these animated films are the strongest form of representation for young children who are easily influenced by the characters and stories they watch. For this reason, I believe analyzing concepts of the border in Disney’s/Pixar's 2017 animated feature Coco is crucial to the discussion of the representation, or misrepresentation of the border.

I’ve watched this film multiple times: the first time in English, on my own, in a crowded theatre with a multitude of children surrounding me, the second time in Spanish with my family, and the third time in English with Dartmouth friends after returning from our winter break. Each time was a radically different experience as the environment and the company in which I watched Coco changed each time.

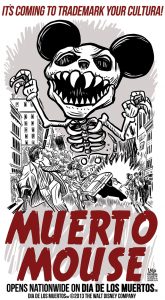

Coco incorporates Latinx representation through the cultural consultant, Mexican-American cartoonist and critic, Lalo Alcarez and at least three other Mexican descendant cultural consultants as well as an all-Latinx lyrics team and a large cast of Latinx actors. It tells a story of El Dia de Los Muertos that is celebrated in some Latin American countries and has its roots in indigenous religious practices (none of which were mentioned in the film – only representing and appealing to a mestizo/white-Latinx audience). On top of the misrepresentation of the holiday in the film, during pre-production there was a huge backlash from the Latinx community in 2013 when Disney attempted to trademark the cultural holiday and make a profit from the copyright laws.

This was the main reason why Disney/Pixar decided to take on Mexican cultural consultants – as a response to the backlash, not as forethought to create the best possible representation of a culture.

The film follows a young Miguel through his love of music and the complex relationship with his family’s ban on anything musical. He travels to the realm of the dead on Dia de Los Muertos and must find his long lost great-grandfather to reverse a curse that will bring him back to the realm of the living. Instead of following the lead of the indigenous beliefs of the after life as being a place rid of any class, race, or gendered society, Coco does the opposite and makes the realm of the dead a skeletal mirror clad in a sombrero and calaveras of our capitalist, racist, and sexist society. Class divides still exist in this after life. Gender roles still exist. Poverty is prevalent in the slums of the dead. And the only way to enter this disappointing after life is to cross a border and get past immigration – the wall continues in the after life as well.

As I watched Coco for the first time and witnessed the border patrol and bridge that commanded the after life, I felt my stomach drop. Not even in the after life are we free of capitalist borders and even here the dead are dehumanized. In a film that was supposed to build bridges and give a voice to those that have been widely underrepresented, Disney/Pixar only reinforces the dehumanizing ideas of the border and further highlights the classicized and racialized discrepancies of who gets to easily navigate spaces of power and who gets left behind.

The photographs on the ofrendas of the dead’s loved ones act as their passports into the living realm and allow them to be reunited with their families for one day out of the year. But what happens when the living don’t have any photographs of their loved ones that have passed? What happens when the living don’t have the financial means for an ofrenda? What happens when those that are dead have no family? Deportation. In the scene below we see exactly this, as Héctor attempts to cross the bridge to get to his loved ones and border officials deport him.

As we watch Héctor be dragged away by border patrol, in the forefront we hear Miguel’s aunt tell him “I don’t know what I’d do if no one put up my foto”, only to witness the way in which Miguel, with the help of his family and positionality, is able to cross into the realm of the dead with no problem.

There was no reason for this border, for this bridge that acts as a border patrol tool for deportation, or for the utilization of ofrenda photographs as passports. But here Disney/Pixar takes another opportunity to influence our youth on the supposed necessity of borders and the policing of these borders but it fails to educate them on the dehumanization that these borders promote.

Organizations such as Yo Tengo Nombre are working against this narrative by creating a database that brings closure to the families who have lost their loved ones to the dangers of the Mexican-U.S. border. They collect and photograph the belongings of those that have died at the border and allow loved ones, activist and humane organizations the ability to search for any traces of recognition so that these people do not remain nameless and unknown, much like the way Héctor is abandoned in the after life.